Sylvia: A 19th Century Life Unveiled

by Stacy Renee Morrison

Exhibition Overview

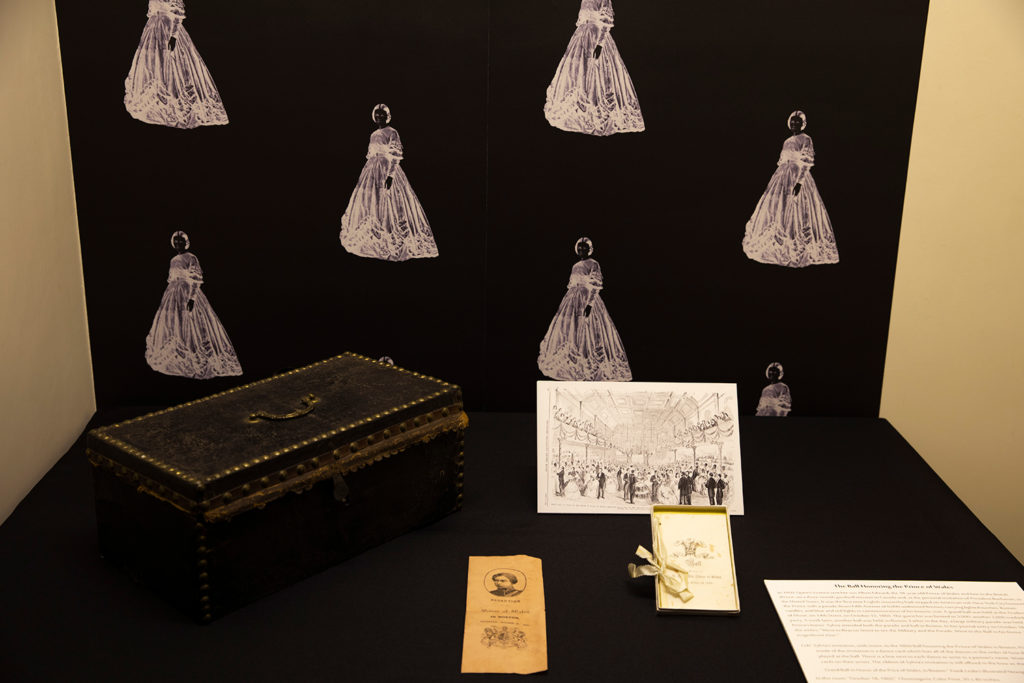

A photograph of two young girls dressed in mourning, their hair tightly braided; torn pieces of wallpaper; tiny perfume bottles; an invitation to a ball in 1860 honoring the Prince of Wales – all cherished keepsakes found in a small timeworn leather trunk discarded on a Manhattan sidewalk in 2002.

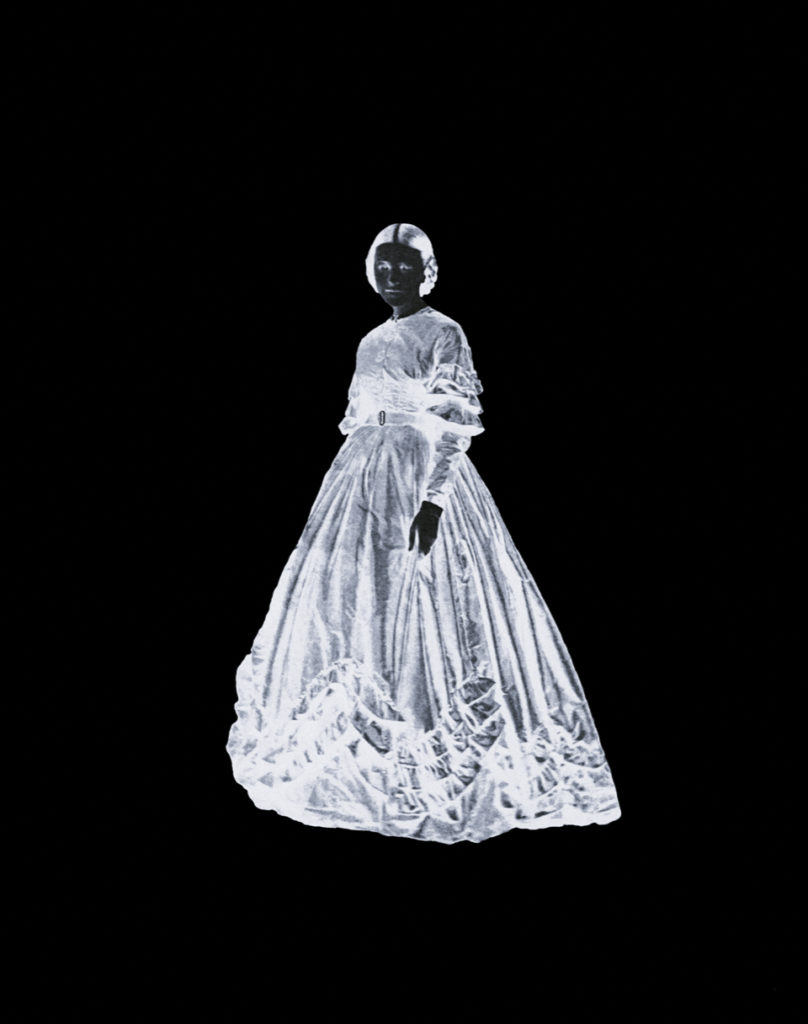

The contents of the trunk, myriad fragments of a greater life story, inexplicably haunted me beyond the parameters of pleasant curiosity. I was compelled to give identity to this anonymous 19th century woman, both forgotten by time and abandoned for garbage. I knew I was her last hope. As an artist, it was my natural inclination to make her my subject, to canonize her life story left unclear. For almost two decades now, I have been on an obsessive quest to weave together her life.

Her name is Sylvia DeWolf Ostrander.

Born Sylvia Russell Bullock, in 1841, she was the first child of Judge Jonathan Russell Bullock and Susan Amelia DeWolf, and raised in Bristol, Rhode Island. In 1860, Sylvia’s father was elected Lieutenant Governor of Rhode Island; in 1865, he was nominated for the U.S. District Court for Rhode Island by President Abraham Lincoln, confirmed by the U.S. Senate, and served until 1869. On her mother’s side, the DeWolfs made their fortune in the Triangle Trade.

Sylvia had four siblings: Annie, two years younger and to whom she was especially close, Charles, Elizabeth, and a half-sister, Emma, from her father’s second marriage. (Sylvia’s mother died in 1866.) As a teenager, she attended the Warren’s Ladies Seminary, a finishing school in a neighboring town to Bristol.

In 1862, at the age of 21, she married William Davis Dimock. Following a wedding trip to Niagara Falls, the newlyweds took up residence on West 22nd Street, in the residential Chelsea neighborhood of New York City. In her journals during the 1860s, Sylvia reports hearing Charles Dickens read, going to showman P.T. Barnum’s American Museum, and eating often at the fashionable Delmonico’s (which provided the supper at the Grand Ball welcoming the Prince of Wales to New York in 1860). She witnessed the city become the cosmopolitan metropolis it is today.

Sylvia had one child, a son, William DeWolf Dimock, born in 1864. She was widowed nine years later. In 1884, she married wealthy businessman Cornelius Van Buren Ostrander, who died just three weeks after their wedding. He was 77, she 43. Sylvia died at her home on Church Street in Bristol, Rhode Island, in 1925, at the age of 84. At her wake in the front parlor a small quartet played.

This exhibition displays remnants of Sylvia’s 19th century life and the ways she now lives on in the 21st century through me.

| …. |

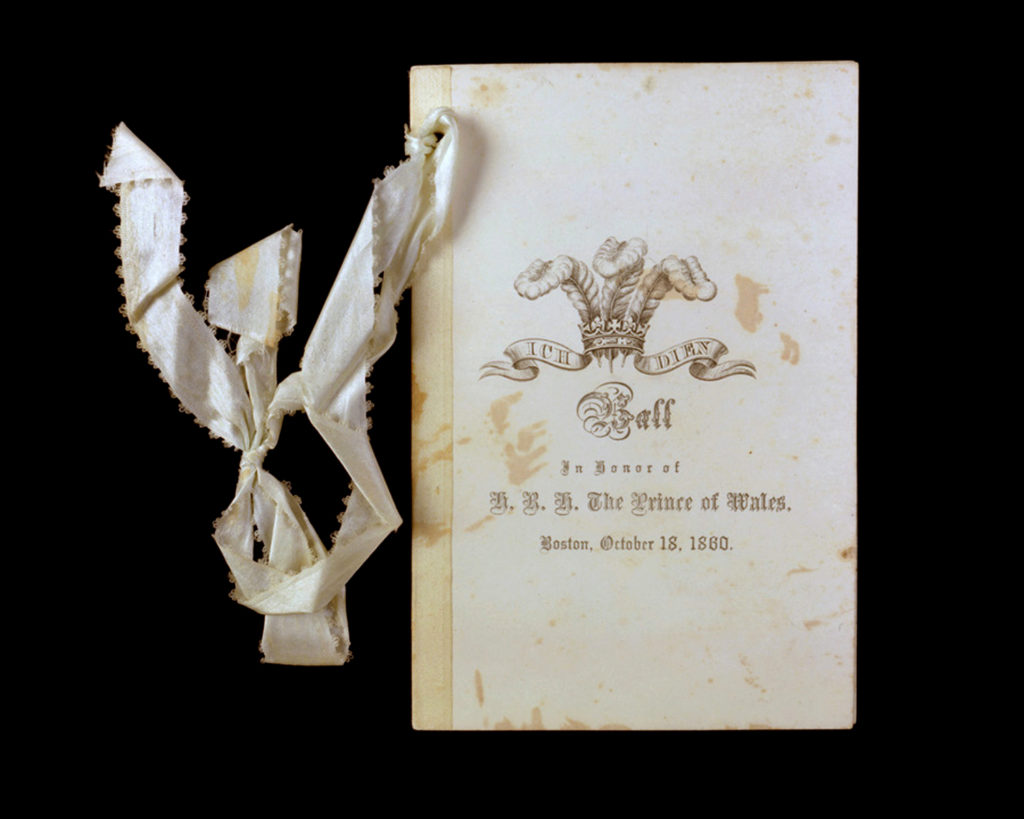

The Ball Honoring the Prince of Wales

In 1860, Queen Victoria sent her son Albert Edward, the 18-year-old Prince of Wales and heir to the British throne, on a three-month goodwill mission to Canada and, at the personal invitation of President Buchanan, to the United States. It was the first time English monarchy had stepped on American soil. New York City honored the Prince with a parade down Fifth Avenue of 6,000 uniformed firemen carrying lighted torches, Roman candles, and blue and red lights in commemoration of his historic visit. A grand ball was held at the Academy of Music, on 14th Street, on October 12, 1860. The guest list was limited to 3,000; another 2,000 crashed the party. A week later, another ball was held, in Boston. Earlier in the day, a large military parade was held in the Prince’s honor. Sylvia attended both the parade and ball in Boston. In her journal entry on October 18, 1860, she writes: “Went to Beacon Street to see the Military and the Parade. Went to the Ball in his honor. Had a magnificent time.”

Sylvia’s invitation, with insert, to the 1860 Ball honoring the Prince of Wales in Boston. Printed on the inside of the invitation is a dance card which lists all of the dances in the order of how they were to be played at the ball. There is a line next to each dance to write in a partner’s name. Women wore the dance cards on their wrists. The ribbon of Sylvia’s invitation is still affixed in the bow as she wore it.

Please Donate to Our Future!

Each dollar we receive will help keep us thriving through this crisis and beyond,

ensuring that the museum remains a pillar of education of 19th century New York.

Click here to make a donation.

Sylvia: A 19th Century Life Unveiled |

||||

.

..Overview... |

..Sylvia’s Story: The Beginning.. |

..Sylvia’s Life Unveiled.. |

..No-When.. |

..Sylvia as Muse.. |