Julia Tredwell’s Letter from Richfield Springs, NY

by Merchant's House Museum

Julia Eliza Tredwell, Seabury and Eliza’s sixth child, was born on May 16, 1833. She was two years old when her father purchased the house on East Fourth Street that would be Julia’s home until her death in 1909, at the age of 76. A large number of books in the Tredwell Books Collection bear her name, including several on French language and grammar, natural history, poetry, and mathematics.

Julia Eliza Tredwell, Seabury and Eliza’s sixth child, was born on May 16, 1833. She was two years old when her father purchased the house on East Fourth Street that would be Julia’s home until her death in 1909, at the age of 76. A large number of books in the Tredwell Books Collection bear her name, including several on French language and grammar, natural history, poetry, and mathematics.

Julia is pictured at right, ca. 1862.

In an undated letter in the museum’s archive, Julia wrote to her mother from Richfield Springs, in upstate New York, where she apparently went to recover from an illness. Richfield Springs became popular in the 1830s after Dr. Horace Manley purchased the site of the Great White Sulphur Springs, built a bath house, and brought 25 patients to take the water cure. It became increasingly popular as a summer resort.

“I have felt very much better the past week. They all say I have gained. I feel it, but by weight I only have gained two pounds. I took a bath and I felt stronger as soon as I came out … It is so lonesome to be separated that I feel as if I ought not to stay as long as I have, but I hope in so doing that I will quite gain my strength.”

Coming Soon! Miracle on Fourth Street

by Merchant's House Museum

Museum Historian Mary Knapp’s new book, Miracle on Fourth Street: Saving an Old Merchant’s House, is coming soon.

Here’s what Mrs. Knapp has to say:

August, 1933—The country was in the depths of the Great Depression. Gertrude Tredwell had just died at the age of 93 in the 1832 rowhouse her family had inhabited for almost 100 years. A century of urban progress meant that the house, once located in the New York City’s most desirable neighborhood, was now just steps from the Bowery, the nation’s skid row. It was a time capsule, complete with the original owners’ furnishings dating to mid 19th century, and personal belongings as well—books, decorative objects, textiles, and even 39 dresses belonging to the women of the family.

Enter George Chapman, a distant cousin who made what can only be described as a foolhardy decision to “save” the old house from the auction block and turn it into a museum. Not only had the old house been long neglected and was then well along the road to disintegration, but certainly no one at that time was inclined to donate money to preserving the home of an early New York City merchant—a rich merchant, to be sure—a good man certainly—but not a person of historical significance.

Enter George Chapman, a distant cousin who made what can only be described as a foolhardy decision to “save” the old house from the auction block and turn it into a museum. Not only had the old house been long neglected and was then well along the road to disintegration, but certainly no one at that time was inclined to donate money to preserving the home of an early New York City merchant—a rich merchant, to be sure—a good man certainly—but not a person of historical significance.

But George was a wealthy man and in spite of increasing physical infirmity he just barely managed to hold his beloved museum together at great personal cost for over 20 years. However, he was not inclined to make major repairs let alone the needed thorough restoration of the collapsing house.

Eventually, after an improbable chain of events, an impeccable authentic restoration did take place, undertaken without charge by Joseph Roberto, an accomplished restoration architect who exercised a scrupulous regard for the original fabric of the building and recruited some of the most talented craftsmen in the country as well as White House architect, Edward Vason Jones and noted 19th century authority on American decorative arts, Berry Tracy, as pro bono consultants.

The restoration was a story of creative solutions to structural calamities, heartbreaking setbacks, personality conflicts, and an unceasing struggle to find funding, but Joseph Roberto simply would not give up, and eventually the house was restored to its original beauty, structurally stronger than ever. The textiles had completely deteriorated, but instead of replacing them with period appropriate examples, The Decorators Club, who were responsible for the interior refurbishment, wisely had the original silk curtains and the carpeting reproduced at extraordinary expense.

The story doesn’t end there, however, for there was to be one last crisis, which could literally have brought the house down were it not for the wise direction of the current director and the support of government and corporate grants, and the generosity of private donors.

Since the beginning, The Merchant’s House has held an unworldly attraction for all those who have been involved in its long life. It is not an exaggeration to say that people simply fall in love with it and are willing to devote extraordinary effort to its preservation.

Maybe that’s because of what happens when you cross the threshold.

Which brings me to the most miraculous circumstance of all. Here we come as close as we ever will to those who came before us. As we tune in to the height of the ceilings and the nearness of the walls, as we travel a path from room to room, observing the light, seeing what the family saw in those rooms—the piano, the mirrors, the Duncan Phyfe chairs, their four poster beds—we learn with our bodies as well as our brains what it was like to live in a 19th century urban rowhouse owned by one of the early merchants who laid the commercial foundations of this great city.

Once there were hundreds of such homes lining the streets of the neighborhood north of Bleecker. Now there is only one left to tell the story.

“The Habits of Good Society” — Etiquette & Entertaining at Home

by Merchant's House Museum

On Saturday, April 23rd 2016, from 12 to 4 p.m., the Merchant’s House brings you “The Habits of Good Society” – Etiquette and Entertaining at Home, part of our ongoing Tredwells at Home, Living History series.

On Saturday, April 23rd 2016, from 12 to 4 p.m., the Merchant’s House brings you “The Habits of Good Society” – Etiquette and Entertaining at Home, part of our ongoing Tredwells at Home, Living History series.

It’s 1858 and 25-year-old Tredwell daughter Julia (pictured left) is receiving visitors in the front parlor. New York women in the 19th century maintained friendships and other social connections through the elaborate ritual of formal visiting — or “calling” — and in order to participate, everyone was expected to know the rules. When do you make a personal call, and when can you leave a calling card? How soon should you pay a “party call” after attending a ball or formal dinner? How do you know when a family is ready to receive visitors after mourning a death? What is a “sociable”? Come pay Julia a call and find out how she and other young women in 19th century New York navigate the ins and outs of fashionable society.

This event is included with the price or regular admission and is open to all ages. Julia will be in the parlor to meet visitors from 12 to 4 p.m. 19th century attire is encouraged.

NEW Tour! “In the Footsteps of Bridget Murphy: The Life of an Irish Servant.”

by Merchant's House Museum

The Merchant’s House Museum now offers a brand new signature tour, “In the Footsteps of Bridget Murphy: The Life of an Irish Servant.”

The only one of its kind in New York City, this unparalleled “back-stairs” tour tells the heroic story of the Irish women who worked in domestic service in 19th Century New York, overcoming homesickness, culture shock, and prejudice to cultivate a new home and a new identity on foreign soil – ultimately altering the face of New York City forever.

The Irish domestic servant in 19th century New York City

It is widely known that Irish women made up a large proportion of the servant class in 19th century New York. And the sheer amount of physical work they performed is taken as a given… though can we really imagine what wringing out hundreds of pounds of heavy, sopping wet laundry feels like? Yet even if we give them credit for their labor, we often fail to give them credit for their resiliency and the adroitness with which they adapted to a vastly different and complex new environment.

It is widely known that Irish women made up a large proportion of the servant class in 19th century New York. And the sheer amount of physical work they performed is taken as a given… though can we really imagine what wringing out hundreds of pounds of heavy, sopping wet laundry feels like? Yet even if we give them credit for their labor, we often fail to give them credit for their resiliency and the adroitness with which they adapted to a vastly different and complex new environment.

Beyond the endless physical toil their positions demanded, these female domestic workers were also busy adapting to a new culture, decoding the vagaries of their employers, and parsing the subtle social intricacies of work in a big house. These girls, some only in their teens, soon learned to navigate this bewildering new world, becoming indispensable to running the household. Demand was so high that a more experienced servant had a surprising amount of power in negotiating her pay and other benefits; servants saved astonishing amounts of their salaries to send back home to Ireland.

Photo by Hal Hirshorn.

Into their home, into their world

“In the Footsteps of Bridget Murphy” takes guests up the narrow stars to the 4th floor servants’ quarters, where the Tredwell family’s four Irish servants – Bridget Murphy, Mary James, Mary Smith, and Ann Clark – lived and did some of their work. The entire hour-long tour takes place the original setting where these women lived and worked, bringing you into their home, their lives, and their world – in what is “arguably the oldest intact site of Irish habitation in New York City.” (Time Out New York)

“In the Footsteps of Bridget Murphy: The Life of an Irish Servant” is available on select dates or as a private group tour; please visit our Group Programs Page for more information.

New Spin for a Tredwell Dress

Recently, the Merchant’s House collaborated with 3D modeling firm PaleoWest Archaeology to create an interactive 3D model of the two-piece spring and summer cotton dress, 1862-1865 (MHM 2002.0840), on display through April 29, one of the 39 dresses in the Tredwell Costume Collection. The model allows the viewer to look at the dress from all angles and zoom in on details. In the coming years, as each dress is displayed, we plan on creating similar models of dresses.

Merchant’s House Museum Tredwell Dress

by PaleoWest Archaeology

on Sketchfab

Merchant’s House on “Blueprint: NYC”

This week, Blueprint: New York City featured a brilliant and beautiful 30 minutes of the Merchant’s House on NYC Media, the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment.

“… nothing inside or out has changed … a time capsule hiding in plain sight.”

Watch the full episode below.

“Sacred to the Memory:” The 150th Anniversary of the Death of Seabury Tredwell

Seabury Tredwell died 150 years ago, on March 7, 1865. He was 85 years old and suffered from Bright’s Disease, an affliction of the kidneys. He was survived by his wife, Eliza, their eight children, and five grandchildren.

Seabury Tredwell died 150 years ago, on March 7, 1865. He was 85 years old and suffered from Bright’s Disease, an affliction of the kidneys. He was survived by his wife, Eliza, their eight children, and five grandchildren.

Custom decreed that the body be placed on view for visitors if at all possible. Seabury Tredwell’s corpse may have been displayed on his bed, a sofa, or in a coffin. His funeral service took place in the double parlor on Saturday, March 11, and was attended by a wide circle of family, friends, and acquaintances. The coffin was then taken to the New York City Marble Cemetery, nearby on Second Street between First and Second Avenues, either by horse-drawn hearse or pall bearers. His body was temporarily interred there, before being ultimately laid to rest in the Tredwell family plot, at Christ’s Church in Hempstead, Long Island. His gravestone, at left, stands alongside his wife, Eliza’s, and five of their children, and bears the epigraph “Sacred to the Memory.”

According to The New York Post, “Among the deaths noticed in our columns today is that of one of our oldest and most respected merchants, Seabury Tredwell. He was a gentleman of the old school, dignified and accomplished in his manners and high-minded and honorable in all his transactions.”

Come pay your last respects as we celebrate the life (and commemorate the death) of “one of New York’s oldest and most respected merchants.” The exhibition is open March 5 to March 30.

Out of Their Boxes: The Tredwell Costume Collection on Display

The Tredwell Costume Collection comprises more than 400 articles of clothing, primarily women’s dresses and their accompanying chemisettes, collars, undersleeves, and petticoats. The core of the collection is a remarkable 39 dresses documented to have been owned and worn by the women of the family. Many are outstanding examples of the 19th-century dressmaker’s art, composed of fine and delicate fabrics and ornamentation.

Currently on display in Eliza Tredwell’s bedroom: a one-piece spring and summer dress, 1859-1864, made of cream-colored sheer muslin with woven cream stripes and a printed black, tan, and red floral pattern. Printing with synthetic aniline dyes, which were discovered and initially produced in 1856, was a less costly way to replicate the look of more expensive, more intricately woven fabrics. This dress, because of its fragile condition, is rarely exhibited.

Of note, this dress is documented in the Index of American Design (IAD) at the National Gallery of Art (image to right). The IAD, a program of the New Deal Federal Art Project, was formed in 1935 to illustrate through watercolor renderings the history of American design in the applied and decorative arts.

Commuter Sleighs?

by Merchant's House Museum

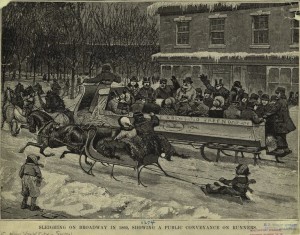

In mid-19th century New York, commuters relied on omnibuses — horse-drawn carriages that seated a dozen passengers, often many more, on wooden benches. (The driver stopped when passengers tugged on a strap attached to his ankle.) After a snow storm, carriages were replaced with sleighs.

In his diary, lawyer George Templeton Strong described commuter sleighs as “insane vehicles” that “carry each its hundred sufferers, of whom about half have to stand in the wet straw with their feet freezing and occasionally stamped on by their fellow travelers, their ears and noses tingling in the bitter wind, their hats always on the point of being blown off.”

The sleighs and sleds of snowy old New York, Ephemeral New York.

This Day in Tredwell Family History: Elizabeth Tredwell Dies

Elizabeth Seabury Tredwell, the eldest child of Eliza and Seabury Tredwell, was born on July 23, 1821, and died on January 7, 1880, at the age of 59. According to her death record, she died of “exhaustion and suffocation from chronic bronchitis.”

Elizabeth Seabury Tredwell, the eldest child of Eliza and Seabury Tredwell, was born on July 23, 1821, and died on January 7, 1880, at the age of 59. According to her death record, she died of “exhaustion and suffocation from chronic bronchitis.”

She married Effingham H. Nichols, a Yale alumnus (Class of 1841) and successful attorney, on April 19, 1845, at St. Bartholomew’s Church, then located around the corner from 4th Street at Great Jones Street and Lafayette Place. St. Bart’s was built in 1835 to accommodate the influx of new residents to the fashionable Bond Street neighborhood.

Following their marriage, the newlyweds lived with her parents in the 4th Street house, as was the custom. Their only child, Elizabeth Howard Nichols, known as Lillie, was born in 1854. (It was Lillie Nichols who inherited the house after her aunt Gertrude Tredwell died in 1933.)

In 1859, the family moved to Brooklyn, then to Fifth Avenue and 34th Street, across from William B. Astor, Jr. and John Jacob Astor, III.

According to Elizabeth’s obituary, published in The New York Times on January 11, 1880, “Relatives and friends of the family are respectfully invited to attend the funeral from her late residence, No. 339 5th av. on Monday, Jan. 12, at 10 o’clock A.M. Internment at Woodlaw Cemetery, by special train from the Grand Central Depot immediately after the service.”

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »