“The Land of the Blacks:” A Free Black Settlement in New Amsterdam

by Ann Haddad

| .. |

A New Park!

With the opening in July 2022 of adjacent Manuel Plaza, the Merchant’s House Museum joined the NoHo community in honoring what is considered to be the first free Black settlement in North America. The plaza is named in recognition of the emancipated people of African descent who farmed land in this area and other parts of Lower Manhattan during the early Dutch period of New York City history, when the colony was named New Amsterdam.

The Dutch Golden Age

The settlement called New Amsterdam was the capital of New Netherland, the first Dutch colony in North America, which extended from Albany in the north to Delaware in the south, and included what are now parts of several Mid-Atlantic and southern states. During the era known as the “Dutch Golden Age,” speculators from the Netherlands, lured by Henry Hudson’s tantalizing description of the east coast of North America and his exploration of the river that now bears his name, saw tremendous commercial opportunities in these territories. One group that formed a trade monopoly was the Dutch West India Company (WIC), made up of merchants, foreign investors, and slave traffickers.

Brought to Work

Only three years after its establishment in 1621, the WIC had arrived to colonize the island of Manahatta, lured by its expansive harbor and its promise of economic success in the forms of abundant arable land, furs, timber, and waters teeming with fish. According to historian Jaap Jacobs, the first group of enslaved Black laborers arrived in New Amsterdam on August 29, 1627, one year after WIC Director Peter Minuet purchased the island of Manahatta from the Lenapes. Eleven Black men (mostly from West Central Africa but also possibly captured Spanish, Brazilian, and Portugese seamen) were imported to cultivate the plantations, work on the bouweries (Dutch for farms), clear forests, and assist with the building of roads, the fort and garrison, and other infrastructure. Among this earliest group of enslaved men were Anthony Portugese, Paulo d’Angola, Simon Congo, and Jan Francisco.

More enslaved men and women followed, typically brought over in small groups; 70% were from the Caribbean. According to the New Netherland Council Minutes, on July 1, 1638, the ship De Hoop was ordered to carry from the island of Curacao “cattle, salt, and negroes, or such goods as may be deemed best for the use of the Company.” The WIC established quarters for the enslaved, about 5.5 miles from the main settlement, along the East River, opposite what is now Roosevelt Island. By 1644, there were approximately 120 enslaved Black people in New Amsterdam. According to Historian Dennis J. Maika, the first ship bearing only enslaved Africans (and funded by Dutch private investors), arrived in New Amsterdam in 1655.

Working the System

Although they were considered inferior to whites, under the governance of the WIC the enslaved were accorded some of the legal rights granted to the colonists. They were permitted to testify in court, sue whites, own property, marry in the Dutch Reformed Church (located inside Fort Amsterdam), and bear arms when the colony was under threat. Historians agree, however, that the enslaved were only granted these rights because the Dutch had yet to establish a legal framework that would govern the lives of those in bondage.

As the following court testimony held at Fort Amsterdam on March 31, 1639 indicates, some of the Black enslaved were able to secure wages for services they provided outside of their enslavement: “Before me, appeared Manuel, the commandant’s servant … who empowered [his attorney] to collect … the sum of 15 guilders, which are due to him from Hendrick Frederickson for wages.”

Kieft’s War

As Black people struggled to make the most of their vague legal standing in New Amsterdam, a number of the enslaved who had served for over 20 years began to petition Director General Kieft for their freedom. The Dutch government, however, was facing another growing concern: as the colonial population grew, the relations with Native Americans, largely of the Lenape tribe, were worsening. As conflicts grew more frequent and threatening, Kieft ordered increasingly aggressive treatment of the Natives, culminating in what was known as “Kieft’s War,” which lasted from 1641 to 1645.

“The Land of the Blacks”

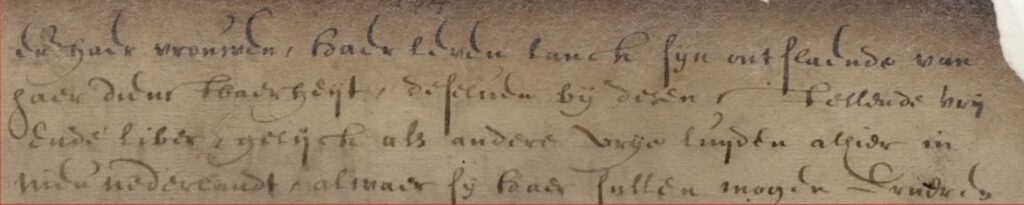

During this period of unrest, while Black people were made to bear arms to fight the Native Americans, the WIC sought to draw settlers closer to New Amsterdam to provide additional protection and barricades against their enemies. A number of land grants were issued to whites in 1643 in the surrounding areas. On February 25, 1644, perhaps realizing that they could simultaneously meet the demands of the Black enslaved and bolster the security of the colony, Kieft and the Council of New Amsterdam legally emancipated 11 of the “company slaves,” and granted them parcels of farmland about a mile north of the settlement. As noted in the Council Minutes, “… we, the director and council, do release the aforesaid Negroes and their wives from their bondage for the term of their natural lives, hereby setting them free and at liberty on the same footing as other free people here In New Netherland, where they shall be permitted to earn their livelihood by agriculture on the land shown and granted to them.”

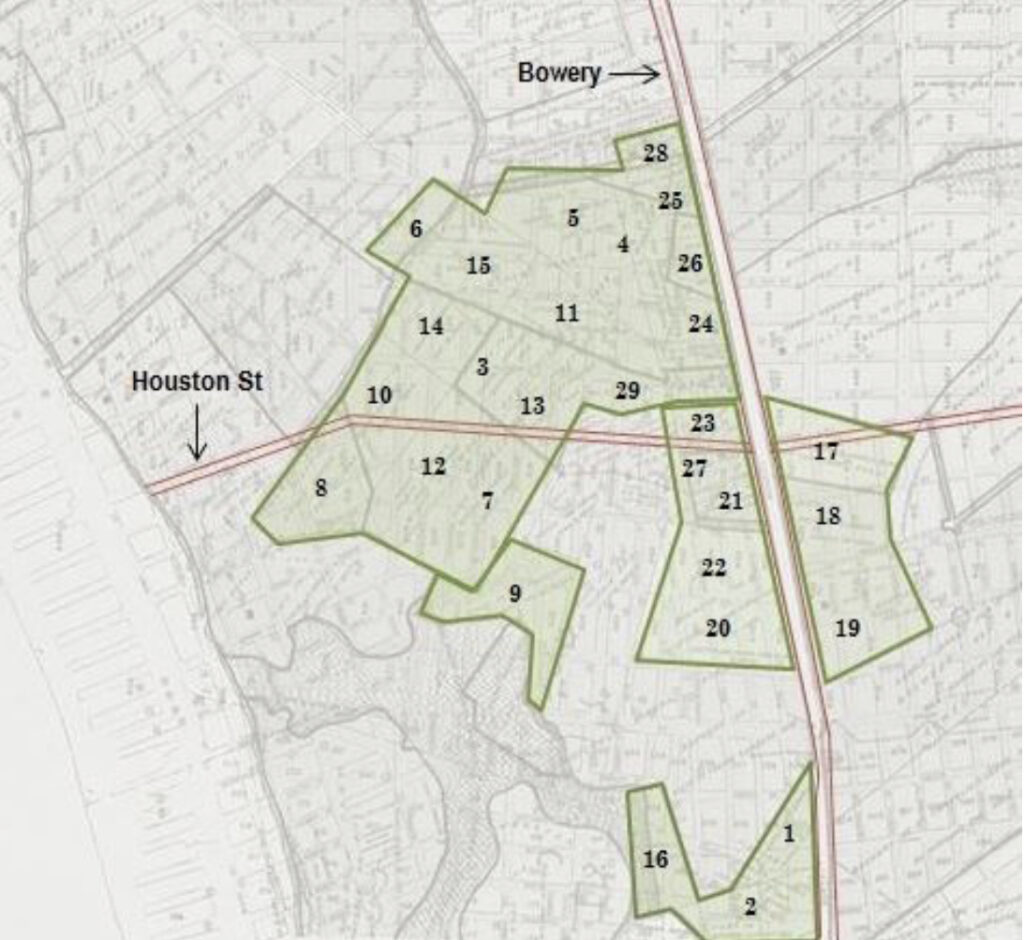

Some of these initial land grants were deeded to members of the settlement’s Black militia, including Domingo Anthony and Manuel Trumpeter, who was known as “Captain of the Blacks.” By 1662, a total of 28 Black men and women were granted their freedom and given land. Called “The Land of the Blacks” in official Dutch records, the northernmost point of this acreage is now defined as Fifth Avenue and Washington Square North, and totaled over 130 acres; it included what is now NoHo, Greenwich Village, and the South Village, as well as parts of the East Village and the Lower East Side. This calculated strategy on Kieft’s part served to create a human wall of manumitted Black people who would be the first defense against threatening Native Americans seeking to attack the Dutch settlement further south.

“Half-Freedom…”

This new freedom was not without conditions, however. The Council Minutes go on to state that, in exchange for their emancipation, the men and women shall “… be bound to pay annually, as long as he lives, to the West India Company or their agent here, 30 schepels of maize, or wheat, pease, or beans, and one fat hog valued at 20 guilders … If any one shall fail to pay the annual recognition, on pain … of forfeiting his freedom and again going back into the servitude of the said Company. With the express condition that their children, at present born or yet to be born, shall remain bound and obligated to serve the honorable West India Company as slaves. Likewise, that the above mentioned men shall be bound to serve the honorable West India Company here on land or water, wherever their services are required, on condition of receiving fair wages from the Company.”

These harsh terms of emancipation, unique to New Netherland, were later labeled by historians as a condition of “half-freedom.” This group of freed Black people was, according to historian Christopher Moore, “the first legally emancipated community of people of African descent in North America.”

Not all the enslaved of New Netherland were owned by the WIC. Some were privately owned and manumitted over the years. For example, in September 1646 the Reverend Johannes Megapolensis freed Jan Francisco, junior, “a Negro, in view of the long and faithful service rendered by him … provided that during the remainder of his life he shall pay yearly as an acknowledgement of his freedom 10 schepels of wheat…”

… But Striving for Full Emancipation

However difficult it was to accept the terms of manumission set forth by the Dutch government, the freed individuals no doubt realized that it was an improved situation from their previous bondage. Yet they persisted in their efforts towards full emancipation for themselves and their families. They petitioned the government to free their children, and some had their children baptized in the Dutch Reformed Church, in the hope that freedom would follow. When that failed, they tried to purchase their children’s liberty, an expensive undertaking that created greater hardship. These futile efforts reflect Stuyvesant’s growing realization of the extreme profits to be made by increasing the slave trade, not only in monetary gain, but also as a way to protect and expand the Dutch settlement. The Dutch completely dominated the Atlantic slave trade in the 17th century. It is not surprising that free Black people harbored runaways.

The Old “Bouwerie” Lane

Before the arrival of the Dutch, today’s Bowery, now considered the oldest street in New York, was an ancient Native American trail named Wickquasgeck that began just north of Fort Amsterdam (near today’s Bowling Green), veered east and ran up to what is now Astor Place. When Wouter von Twiller became Director General of New Netherland in 1633, he claimed part of this site for his huge tobacco plantation; upon his replacement with William Kieft in 1637, the land reverted to the Dutch government and was broken up into farms, including Elbert Herring’s farm. The Bowery footpath was eventually lined with a number of bouwerie (Dutch for farm) as part of the settlement’s defensive strategy, some of which were among those first granted by Kieft.

Thirteen other parcels that were previously part of von Twiller’s plantation, and later Herring’s Farm (and which today extend from Prince Street to Astor Place, and from the west side of the Bowery towards Fifth Avenue), were issued in a second series, from 1651-1662, by Peter Stuyvesant, who replaced Kieft as Director General in 1647, and whose own huge farm, (“Bowery No. 1”), now part of the East Village and Stuyvesant Town, began just to the north. Known as the “Negro Lots,” according to I.N. Phelps Stokes in his Iconography of Manhattan Island (1928), these later grants may have replaced earlier grants that lapsed upon the death of the original emancipated individuals. In 1667, three years after the English gained control of the settlement, provincial Governor Richard Nicoll recorded new versions of the grants that confirmed those issued under Dutch colonial rule.

The End of Dutch Rule

Dutch control of New Netherland came to a sudden end on September 8, 1664, when Peter Stuyvesant surrendered to the English. The colony was immediately renamed New York, and Fort Amsterdam became Fort James. The new British government, while acknowledging the grants that allowed the free Black farmers to own and cultivate approximately 200 acres of land, viewed slavery as an economic necessity, an excellent source of cheap labor and a lucrative trade; and it soon reduced the free Black individuals to alien status, denied their landowning rights, and enacted strict slave codes.

The Growth of the Slave Trade

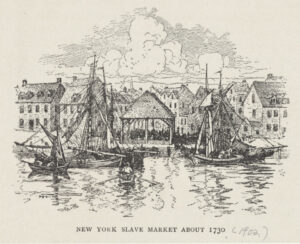

According to Burrows and Wallace in Gotham, the number of enslaved individuals in New York City went from 300 in 1664 to approximately 750 in 1703. That number would greatly increase over the first quarter of the 18th century, as merchants forged strong connections with West Indian plantations due to their abundance of sugar, rum, cotton, and other commodities, as well as slaves; and as more whites began to use the enslaved for domestic servitude and other physical labor. According to historian Eric Foner, between 1700 and 1774 over 7,000 enslaved were imported into New York. To manage the brisk business in slaves, in 1711 New York opened a “slave market” on Wall Street between Pearl and Water Street, which remained in use until 1762.

.

.

.

Relevance to the Merchant’s House Museum Site

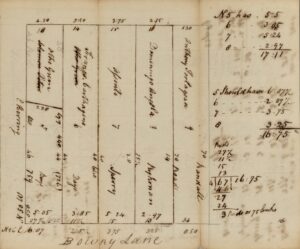

Now let’s take a look at the connection between the first free Black landholdings and the location of the Merchant’s House Museum. In 1796, New York City surveyor Gerard Bancker (1740-1799), mapped out and illustrated the original parcels along the Bowery Lane that had been deeded in the 17th century, and included on the maps the names of the former manumitted owners. This survey was part of a larger effort to lay out the streets, farms, and buildings of early New York. Commissioned by the City government, as well as individuals and organizations, this was most likely done as the city and its residents anticipated the northward movement of the population as the city grew, and were eager to subdivide the huge farms and estates into city-sized lots. The collection of maps, known as the Bancker Plans, offers a detailed, fascinating glimpse of early New York City, and may be found in the Digital Collections of the New York Public Library.

Bancker numbered each of the lots according to the original recorded boundaries of the first Black owners. These lots, which ran perpendicular to the Bowery Lane, are recorded and described in Stokes’ Iconography. Lot No. 1, the most southerly, belonged to Manuel “the Spaniard,” and was originally granted to him in 1651. Lot Number 14 was deeded to “Anthony the Blind Negro”in 1658.

Zooming in on Lot Number 5

The particular section of the parcels in this area issued by Stuyvesant that pertains to the site of the Merchant’s House Museum is Lot Number 5. This parcel sat just north of one granted to Solomon Pieter (date uncertain), and south of the one issued in 1658 to Francisco Carthagena, and east of the parcel deeded in 1643 to Manuel de Gerrit de Rues. Nearly three hundred years later, a portion of this parcel would become the site of the Merchant’s House Museum.

Lot Number 5 was identified as having been granted on May 15, 1664, to one Otto Grim, a white man, by Peter Stuyvesant. So de Reus must have moved from the site. Because the grant Grim received was dated several years later than the surrounding ones, Stokes concludes that Grim’s grant possibly replaced one that had initially been granted to a free Black man but had lapsed for an unknown reason.

Otto Grim

Otto Grim arrived in New Netherland from Bremen, Germany in 1664, at the tail end of Dutch rule. According to Reformed Dutch Church records, in September of that year he married Elsie Jans, a widow, and is referred to as “Captain-at-Arms,” so most likely he was a soldier in the Dutch militia. According to the commissary records of Fort Amsterdam, on October 7, 1661, Grim, “Captain at Arms,” was issued two pounds worth of gunpowder. With his new wife, Grim began his life in New Netherland on the farm on Bowery Lane.

By July 1677, according to tax records, Grim had sold his parcel and moved down to the “Heere Graft,” now Broad Street. He died by 1690, as that is the year his widow Elsje married Benjamin Provoost. Nothing further is known about him.

Research as to the identities of the subsequent owners of the land is ongoing; a future post will focus on these men and women and their occupations. The history will bring us to 1835, when retired hardware merchant Seabury Tredwell purchased the house built in 1832 by hatter Joseph Brewster for $18,000.

History Uncovered

Over the past few years, as more information has been discovered about Black history in New York City, historians concluded that there was nothing humane or “benign” about their treatment. The enslaved who toiled in New York City were subjected to as much abuse and mistreatment as those in the Southern plantations. They were prohibited from trade and forbidden to gather, and were segregated within houses of worship. Over the ensuing years of the 18th century, as their numbers grew, Black New Yorkers fought back against their enslavement, notably through rebellions in 1712 and 1741, and by attempting to self-emancipate by running away from their owners. Many endured terrible punishment and death; as a result, slave laws were tightened. Even New York’s 1799 Gradual Emancipation Law only prolonged the suffering of the enslaved as it served to appease their owners and save the economy from collapse. On July 5th, 1827, slavery was finally outlawed in New York State, but the struggle for equality for Black Americans continued.

The history of the land that the Merchant’s House Museum rests upon is undoubtedly linked to the Black settlement that once occupied the area. Knowledge of the history of “the Land of the Blacks” is an important step towards a broader understanding and dissemination of the full history of Black people in New York City. The Merchant’s House Museum and Manuel Plaza recognize and honor the stories of those Black individuals, both free and enslaved, who helped to create the City of New York, as they worked, struggled against oppression, built community, campaigned for equal rights, and did everything they could to attain freedom.

For a more in-depth look at Black history in New Amsterdam and New York, watch Ann Haddad’s virtual presentation, “Free, ‘Half-Free,’ and Enslaved: Black Life in New Amsterdam.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Berman, Andrew. “North America’s First Free Black Settlement in Our Neighborhoods,” Off the Grid: Village Preservation Blog. 5/25/22. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2022/05/25/north-americas-first-free-Black-settlement-was-in-greenwich-village/.

- Brodhead, John Romeyn. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York. Volume II. Albany: Weed, Parsons & Co., 1858.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Common Council of the City of New York. Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675-1776: in eight volumes. Volume 1 of manuscript minutes. https://archives.org.

- Evjen, John Oluf. Scandanavian Immigrants in New York, 1630-1674. Minn, MI: K.C. Holter Publishing Company, 1916. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books/about Scandinavian_Immigrants_in_New_York_1630.html?id=Eah4AAAAMAAJ

- Faucquez, Anne-Claire. “Corporate Slavery in Seventeenth-Century New York,” in Aje, Lawrence and Catherine Armstrong, eds. The Many Faces of Slavery: New Perspectives on Slave Ownership and Experiences in the Americas. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

- Foner, Eric. Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2015.

- Harris, Leslie M. In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Jacobs, Jaap. “The First Decades of Slavery in New Netherland,” in Black Experience in Dutch New York: New Netherland Institute Annual Conference. YouTube, November 5th, 2021, https://youtube.com/watch?v=eHTp–tm2Zc.

- Lepore, Jill.”The Tightening Vise: Slavery and Freedom in British New York,” in Berlin, Ira, and Leslie M. Harris, eds. Slavery in New York. New York: The New Press, 2005.

- Maika, Dennis J. “The First Slave Traders in New York,” New York Almanack, September 28, 2002. https://www.newyorkalmanack.com.

- Manuscripts and Archives Division, the New York Public Library. (1796) Bowery Lane. Retrieved from

- https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/09ccb840-c6f2-0134-b944-00505686a51c

- Manuscripts and Archives Division, the New York Public Library. (1796) Matthew Buys land in five equal parts, on Bowery Lane. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e73bc7b0-c6f1-0134-8a0e-00505686a51c

- Medford, Edna Greene, ed. Historical Perspectives of the African Burial Ground: New York Blacks and the Diaspora. U.S. General Services Administration. https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/Vol3-HistoricalPerspectivesOfTheNYABG1.pdf.

- Meuwese, Mark. “Kieft’s War: Mass Murder on Manhattan,” New York Akmanack, July 20, 2022. https://www.newyorkalmanack.com.

- Moore, Christopher, “A World of Possibilities: Slavery and Freedom in Dutch New Amsterdam,” in Berlin, Ira, and Leslie M. Harris, eds. Slavery in New York. New York: The New Press, 2005.

- Mosterman, Andrea C. Spaces of Enslavement: A History of Slavery and Resistance in Dutch New York. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2021.

- New York City, Compiled Marriage Index, 1600s-1900s www.ancestry.com.

- New York Landmarks Commission. Noho Historic District Extension Designation Report., May 13th, 2008. https://media.villagepreservation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/15123023/NoHo-Historic-District-Extension-NYC-LPC-Designation-Report.pdf.

- New York Public Library. “‘NYC’s Early African American Settlements: New Amsterdam’s “Little Africa.’” https://libguides.nypl.org/nyc_early_africanamerican_settlements/new_amsterdam.

- New York State Archives. “New Exhibit: The Land of the Blacks.” https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Gallery/280.

- New York State Archives. New Netherland Council Dutch Colonial Patents and Deeds. https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/collections/5513.

- Pelletreau, William S. Early New York Houses. New York: Francis P. Harper, 1900. http://www.ancestraltrackers.org/ny/resources/early-new-york-houses-1900.pdf.

- Purple, Edwin R. Genealogy of The Provoost Family of New York. New York: Privately Printed, 1875. http://dutchgenie.net/GSBC-familyfiles/familyfiles/exhibits/genealogical_notes_of_the_provoost_famil.pdf.

- Purple, Samuel Smith. Index to the Marriage Records from 1639-1801 of the Reformed Dutch Church in New Amsterdam and New York. New York: Privately printed, 1890. https://archive.org/details/indextomarriager00purp/page/n29/mode/2up.

- Sharp, Lewis Inman. The Old Merchant’s House: An 1831/32 New-York Row House. Master of Arts Thesis, University of Delaware, 1968.

- Shorto, Russell. The Island at the Center of the World. New York: Vintage Books, 2004.

- Stokes, I.N. Phelps. The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909. 6 Vols. New York: Robert H. Dodd, 1915-28. https://archive.org/details/iconographyofman06stok/page/123/mode/1up?q=“Otto+grim”.

- U.S. and Canada, Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s. www.ancestry.com.

- Van Laer, Arnold J.F., Translator. New York Historical Manuscripts: Dutch. Volume I Register of the Provincial Secretary, 1638-1642. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1974. https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/files/6514/0151/8811/Volume_I_-_Register_of_the_Provincial_Secretary_1638-1642.pdf#page87.

- Van Laer, Arnold J.F., Translator. New York Historical Manuscripts: Dutch. Volume IV Council Minutes, 1638-1649. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1974. https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/files/9714/0152/0608/Volume_IV_-_Council_Minutes_1638-1649.pdf.

- Van Winkle, Edward. Manhattan 1624 – 1639. New York: Holland Society of America, 1916. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/19040/images/dvm_LocHist005578-00011-0?treeid=&personid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=jfo59&_phstart=successSource&pId=2000000000&rcstate=dvm_LocHist005578-00030-0:765,682,907,730;939,686,1109,732;1588,2083,1748,2129;1571,587,1779,636;2053,598,2175,644;2181,600,2319,649.

- Wall, Diana diZerega. “The Architectural Excavations at the Old Merchant’s House,” in Historic Structure Report, Volume 2, 1993. Merchant’s House Museum Manuscript and Archive Collection.

WEBSITES

- Black Gotham Experience: www.blackgotham.com.

- Netherlands National Archives: www.nationaalarchief.nl/en.

- New Amsterdam History Center: https://newamsterdamhistorycenter.org.

- New Netherland Institute: www.newnetherland.org.

- New York Slavery Records Index. https://nyslavery.commons.gc.cuny.edu.

- New York State Archives: archives.nysed.gov.