“The Land of the Blacks:” A Free Black Settlement in New Amsterdam

by Ann Haddad

| .. |

A New Park!

With the opening in July 2022 of adjacent Manuel Plaza, the Merchant’s House Museum joined the NoHo community in honoring what is considered to be the first free Black settlement in North America. The plaza is named in recognition of the emancipated people of African descent who farmed land in this area and other parts of Lower Manhattan during the early Dutch period of New York City history, when the colony was named New Amsterdam.

The Dutch Golden Age

The settlement called New Amsterdam was the capital of New Netherland, the first Dutch colony in North America, which extended from Albany in the north to Delaware in the south, and included what are now parts of several Mid-Atlantic and southern states. During the era known as the “Dutch Golden Age,” speculators from the Netherlands, lured by Henry Hudson’s tantalizing description of the east coast of North America and his exploration of the river that now bears his name, saw tremendous commercial opportunities in these territories. One group that formed a trade monopoly was the Dutch West India Company (WIC), made up of merchants, foreign investors, and slave traffickers.

Brought to Work

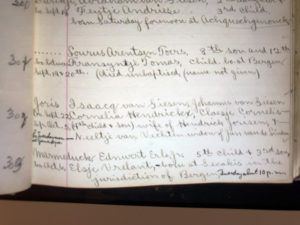

Only three years after its establishment in 1621, the WIC had arrived to colonize the island of Manahatta, lured by its expansive harbor and its promise of economic success in the forms of abundant arable land, furs, timber, and waters teeming with fish. According to historian Jaap Jacobs, the first group of enslaved Black laborers arrived in New Amsterdam on August 29, 1627, one year after WIC Director Peter Minuet purchased the island of Manahatta from the Lenapes. Eleven Black men (mostly from West Central Africa but also possibly captured Spanish, Brazilian, and Portugese seamen) were imported to cultivate the plantations, work on the bouweries (Dutch for farms), clear forests, and assist with the building of roads, the fort and garrison, and other infrastructure. Among this earliest group of enslaved men were Anthony Portugese, Paulo d’Angola, Simon Congo, and Jan Francisco.

More enslaved men and women followed, typically brought over in small groups; 70% were from the Caribbean. According to the New Netherland Council Minutes, on July 1, 1638, the ship De Hoop was ordered to carry from the island of Curacao “cattle, salt, and negroes, or such goods as may be deemed best for the use of the Company.” The WIC established quarters for the enslaved, about 5.5 miles from the main settlement, along the East River, opposite what is now Roosevelt Island. By 1644, there were approximately 120 enslaved Black people in New Amsterdam. According to Historian Dennis J. Maika, the first ship bearing only enslaved Africans (and funded by Dutch private investors), arrived in New Amsterdam in 1655.

Working the System

Although they were considered inferior to whites, under the governance of the WIC the enslaved were accorded some of the legal rights granted to the colonists. They were permitted to testify in court, sue whites, own property, marry in the Dutch Reformed Church (located inside Fort Amsterdam), and bear arms when the colony was under threat. Historians agree, however, that the enslaved were only granted these rights because the Dutch had yet to establish a legal framework that would govern the lives of those in bondage.

As the following court testimony held at Fort Amsterdam on March 31, 1639 indicates, some of the Black enslaved were able to secure wages for services they provided outside of their enslavement: “Before me, appeared Manuel, the commandant’s servant … who empowered [his attorney] to collect … the sum of 15 guilders, which are due to him from Hendrick Frederickson for wages.”

Kieft’s War

As Black people struggled to make the most of their vague legal standing in New Amsterdam, a number of the enslaved who had served for over 20 years began to petition Director General Kieft for their freedom. The Dutch government, however, was facing another growing concern: as the colonial population grew, the relations with Native Americans, largely of the Lenape tribe, were worsening. As conflicts grew more frequent and threatening, Kieft ordered increasingly aggressive treatment of the Natives, culminating in what was known as “Kieft’s War,” which lasted from 1641 to 1645.

“The Land of the Blacks”

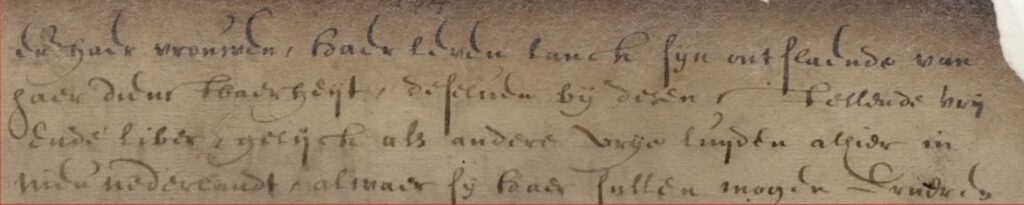

During this period of unrest, while Black people were made to bear arms to fight the Native Americans, the WIC sought to draw settlers closer to New Amsterdam to provide additional protection and barricades against their enemies. A number of land grants were issued to whites in 1643 in the surrounding areas. On February 25, 1644, perhaps realizing that they could simultaneously meet the demands of the Black enslaved and bolster the security of the colony, Kieft and the Council of New Amsterdam legally emancipated 11 of the “company slaves,” and granted them parcels of farmland about a mile north of the settlement. As noted in the Council Minutes, “… we, the director and council, do release the aforesaid Negroes and their wives from their bondage for the term of their natural lives, hereby setting them free and at liberty on the same footing as other free people here In New Netherland, where they shall be permitted to earn their livelihood by agriculture on the land shown and granted to them.”

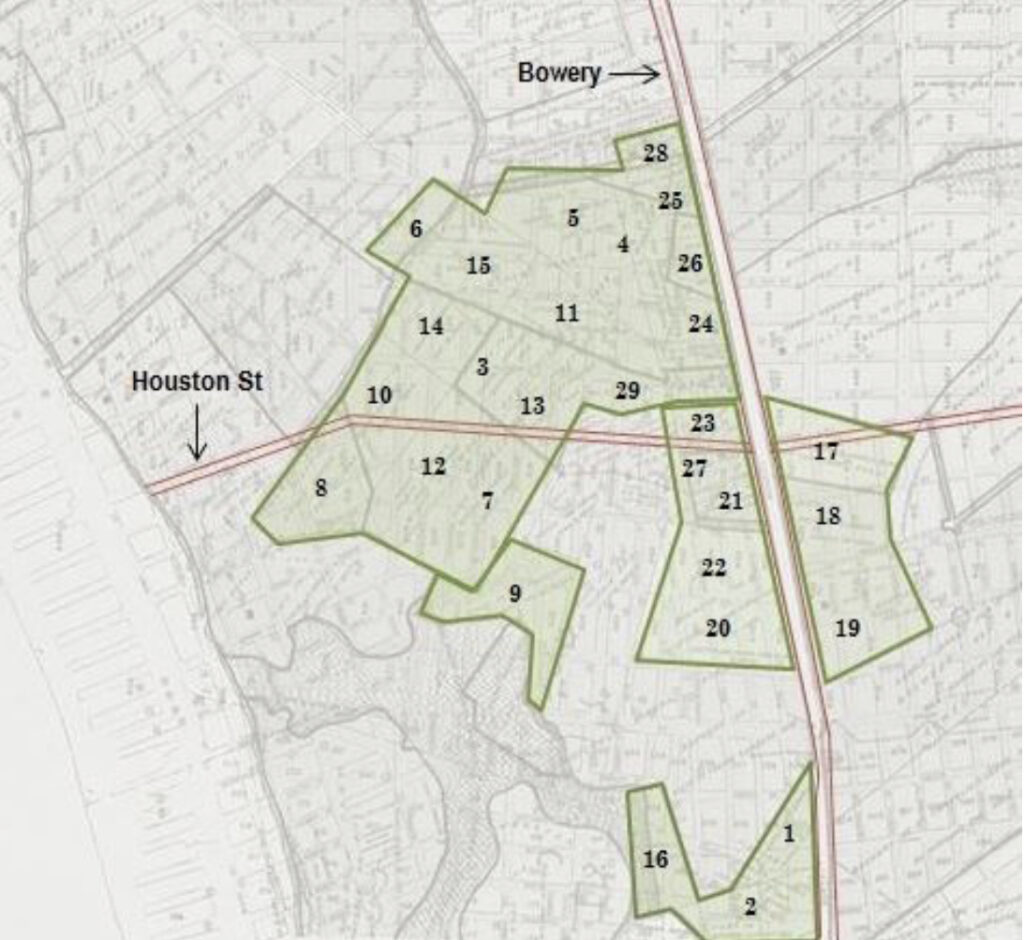

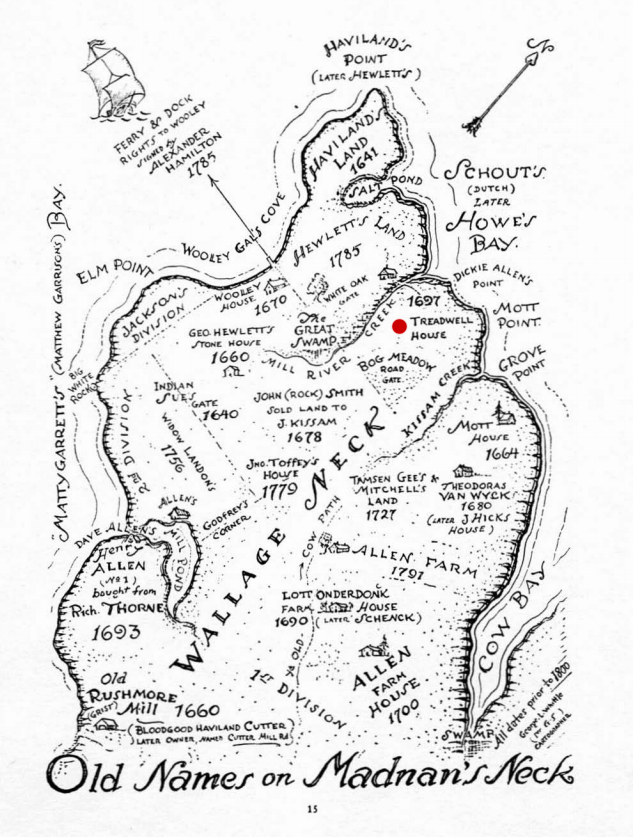

Some of these initial land grants were deeded to members of the settlement’s Black militia, including Domingo Anthony and Manuel Trumpeter, who was known as “Captain of the Blacks.” By 1662, a total of 28 Black men and women were granted their freedom and given land. Called “The Land of the Blacks” in official Dutch records, the northernmost point of this acreage is now defined as Fifth Avenue and Washington Square North, and totaled over 130 acres; it included what is now NoHo, Greenwich Village, and the South Village, as well as parts of the East Village and the Lower East Side. This calculated strategy on Kieft’s part served to create a human wall of manumitted Black people who would be the first defense against threatening Native Americans seeking to attack the Dutch settlement further south.

“Half-Freedom…”

This new freedom was not without conditions, however. The Council Minutes go on to state that, in exchange for their emancipation, the men and women shall “… be bound to pay annually, as long as he lives, to the West India Company or their agent here, 30 schepels of maize, or wheat, pease, or beans, and one fat hog valued at 20 guilders … If any one shall fail to pay the annual recognition, on pain … of forfeiting his freedom and again going back into the servitude of the said Company. With the express condition that their children, at present born or yet to be born, shall remain bound and obligated to serve the honorable West India Company as slaves. Likewise, that the above mentioned men shall be bound to serve the honorable West India Company here on land or water, wherever their services are required, on condition of receiving fair wages from the Company.”

These harsh terms of emancipation, unique to New Netherland, were later labeled by historians as a condition of “half-freedom.” This group of freed Black people was, according to historian Christopher Moore, “the first legally emancipated community of people of African descent in North America.”

Not all the enslaved of New Netherland were owned by the WIC. Some were privately owned and manumitted over the years. For example, in September 1646 the Reverend Johannes Megapolensis freed Jan Francisco, junior, “a Negro, in view of the long and faithful service rendered by him … provided that during the remainder of his life he shall pay yearly as an acknowledgement of his freedom 10 schepels of wheat…”

… But Striving for Full Emancipation

However difficult it was to accept the terms of manumission set forth by the Dutch government, the freed individuals no doubt realized that it was an improved situation from their previous bondage. Yet they persisted in their efforts towards full emancipation for themselves and their families. They petitioned the government to free their children, and some had their children baptized in the Dutch Reformed Church, in the hope that freedom would follow. When that failed, they tried to purchase their children’s liberty, an expensive undertaking that created greater hardship. These futile efforts reflect Stuyvesant’s growing realization of the extreme profits to be made by increasing the slave trade, not only in monetary gain, but also as a way to protect and expand the Dutch settlement. The Dutch completely dominated the Atlantic slave trade in the 17th century. It is not surprising that free Black people harbored runaways.

The Old “Bouwerie” Lane

Before the arrival of the Dutch, today’s Bowery, now considered the oldest street in New York, was an ancient Native American trail named Wickquasgeck that began just north of Fort Amsterdam (near today’s Bowling Green), veered east and ran up to what is now Astor Place. When Wouter von Twiller became Director General of New Netherland in 1633, he claimed part of this site for his huge tobacco plantation; upon his replacement with William Kieft in 1637, the land reverted to the Dutch government and was broken up into farms, including Elbert Herring’s farm. The Bowery footpath was eventually lined with a number of bouwerie (Dutch for farm) as part of the settlement’s defensive strategy, some of which were among those first granted by Kieft.

Thirteen other parcels that were previously part of von Twiller’s plantation, and later Herring’s Farm (and which today extend from Prince Street to Astor Place, and from the west side of the Bowery towards Fifth Avenue), were issued in a second series, from 1651-1662, by Peter Stuyvesant, who replaced Kieft as Director General in 1647, and whose own huge farm, (“Bowery No. 1”), now part of the East Village and Stuyvesant Town, began just to the north. Known as the “Negro Lots,” according to I.N. Phelps Stokes in his Iconography of Manhattan Island (1928), these later grants may have replaced earlier grants that lapsed upon the death of the original emancipated individuals. In 1667, three years after the English gained control of the settlement, provincial Governor Richard Nicoll recorded new versions of the grants that confirmed those issued under Dutch colonial rule.

The End of Dutch Rule

Dutch control of New Netherland came to a sudden end on September 8, 1664, when Peter Stuyvesant surrendered to the English. The colony was immediately renamed New York, and Fort Amsterdam became Fort James. The new British government, while acknowledging the grants that allowed the free Black farmers to own and cultivate approximately 200 acres of land, viewed slavery as an economic necessity, an excellent source of cheap labor and a lucrative trade; and it soon reduced the free Black individuals to alien status, denied their landowning rights, and enacted strict slave codes.

The Growth of the Slave Trade

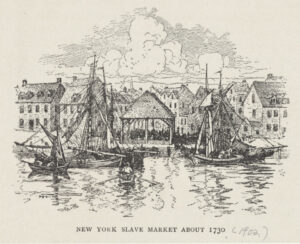

According to Burrows and Wallace in Gotham, the number of enslaved individuals in New York City went from 300 in 1664 to approximately 750 in 1703. That number would greatly increase over the first quarter of the 18th century, as merchants forged strong connections with West Indian plantations due to their abundance of sugar, rum, cotton, and other commodities, as well as slaves; and as more whites began to use the enslaved for domestic servitude and other physical labor. According to historian Eric Foner, between 1700 and 1774 over 7,000 enslaved were imported into New York. To manage the brisk business in slaves, in 1711 New York opened a “slave market” on Wall Street between Pearl and Water Street, which remained in use until 1762.

.

.

.

Relevance to the Merchant’s House Museum Site

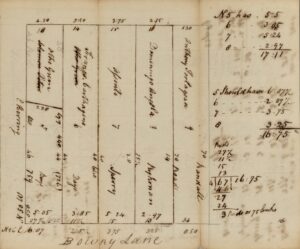

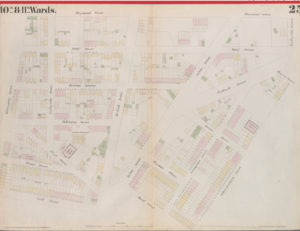

Now let’s take a look at the connection between the first free Black landholdings and the location of the Merchant’s House Museum. In 1796, New York City surveyor Gerard Bancker (1740-1799), mapped out and illustrated the original parcels along the Bowery Lane that had been deeded in the 17th century, and included on the maps the names of the former manumitted owners. This survey was part of a larger effort to lay out the streets, farms, and buildings of early New York. Commissioned by the City government, as well as individuals and organizations, this was most likely done as the city and its residents anticipated the northward movement of the population as the city grew, and were eager to subdivide the huge farms and estates into city-sized lots. The collection of maps, known as the Bancker Plans, offers a detailed, fascinating glimpse of early New York City, and may be found in the Digital Collections of the New York Public Library.

Bancker numbered each of the lots according to the original recorded boundaries of the first Black owners. These lots, which ran perpendicular to the Bowery Lane, are recorded and described in Stokes’ Iconography. Lot No. 1, the most southerly, belonged to Manuel “the Spaniard,” and was originally granted to him in 1651. Lot Number 14 was deeded to “Anthony the Blind Negro”in 1658.

Zooming in on Lot Number 5

The particular section of the parcels in this area issued by Stuyvesant that pertains to the site of the Merchant’s House Museum is Lot Number 5. This parcel sat just north of one granted to Solomon Pieter (date uncertain), and south of the one issued in 1658 to Francisco Carthagena, and east of the parcel deeded in 1643 to Manuel de Gerrit de Rues. Nearly three hundred years later, a portion of this parcel would become the site of the Merchant’s House Museum.

Lot Number 5 was identified as having been granted on May 15, 1664, to one Otto Grim, a white man, by Peter Stuyvesant. So de Reus must have moved from the site. Because the grant Grim received was dated several years later than the surrounding ones, Stokes concludes that Grim’s grant possibly replaced one that had initially been granted to a free Black man but had lapsed for an unknown reason.

Otto Grim

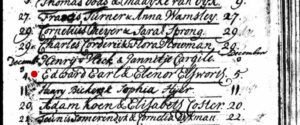

Otto Grim arrived in New Netherland from Bremen, Germany in 1664, at the tail end of Dutch rule. According to Reformed Dutch Church records, in September of that year he married Elsie Jans, a widow, and is referred to as “Captain-at-Arms,” so most likely he was a soldier in the Dutch militia. According to the commissary records of Fort Amsterdam, on October 7, 1661, Grim, “Captain at Arms,” was issued two pounds worth of gunpowder. With his new wife, Grim began his life in New Netherland on the farm on Bowery Lane.

By July 1677, according to tax records, Grim had sold his parcel and moved down to the “Heere Graft,” now Broad Street. He died by 1690, as that is the year his widow Elsje married Benjamin Provoost. Nothing further is known about him.

Research as to the identities of the subsequent owners of the land is ongoing; a future post will focus on these men and women and their occupations. The history will bring us to 1835, when retired hardware merchant Seabury Tredwell purchased the house built in 1832 by hatter Joseph Brewster for $18,000.

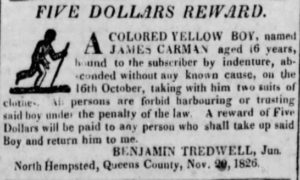

History Uncovered

Over the past few years, as more information has been discovered about Black history in New York City, historians concluded that there was nothing humane or “benign” about their treatment. The enslaved who toiled in New York City were subjected to as much abuse and mistreatment as those in the Southern plantations. They were prohibited from trade and forbidden to gather, and were segregated within houses of worship. Over the ensuing years of the 18th century, as their numbers grew, Black New Yorkers fought back against their enslavement, notably through rebellions in 1712 and 1741, and by attempting to self-emancipate by running away from their owners. Many endured terrible punishment and death; as a result, slave laws were tightened. Even New York’s 1799 Gradual Emancipation Law only prolonged the suffering of the enslaved as it served to appease their owners and save the economy from collapse. On July 5th, 1827, slavery was finally outlawed in New York State, but the struggle for equality for Black Americans continued.

The history of the land that the Merchant’s House Museum rests upon is undoubtedly linked to the Black settlement that once occupied the area. Knowledge of the history of “the Land of the Blacks” is an important step towards a broader understanding and dissemination of the full history of Black people in New York City. The Merchant’s House Museum and Manuel Plaza recognize and honor the stories of those Black individuals, both free and enslaved, who helped to create the City of New York, as they worked, struggled against oppression, built community, campaigned for equal rights, and did everything they could to attain freedom.

For a more in-depth look at Black history in New Amsterdam and New York, watch Ann Haddad’s virtual presentation, “Free, ‘Half-Free,’ and Enslaved: Black Life in New Amsterdam.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Berman, Andrew. “North America’s First Free Black Settlement in Our Neighborhoods,” Off the Grid: Village Preservation Blog. 5/25/22. https://www.villagepreservation.org/2022/05/25/north-americas-first-free-Black-settlement-was-in-greenwich-village/.

- Brodhead, John Romeyn. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York. Volume II. Albany: Weed, Parsons & Co., 1858.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Common Council of the City of New York. Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675-1776: in eight volumes. Volume 1 of manuscript minutes. https://archives.org.

- Evjen, John Oluf. Scandanavian Immigrants in New York, 1630-1674. Minn, MI: K.C. Holter Publishing Company, 1916. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books/about Scandinavian_Immigrants_in_New_York_1630.html?id=Eah4AAAAMAAJ

- Faucquez, Anne-Claire. “Corporate Slavery in Seventeenth-Century New York,” in Aje, Lawrence and Catherine Armstrong, eds. The Many Faces of Slavery: New Perspectives on Slave Ownership and Experiences in the Americas. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

- Foner, Eric. Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2015.

- Harris, Leslie M. In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Jacobs, Jaap. “The First Decades of Slavery in New Netherland,” in Black Experience in Dutch New York: New Netherland Institute Annual Conference. YouTube, November 5th, 2021, https://youtube.com/watch?v=eHTp–tm2Zc.

- Lepore, Jill.”The Tightening Vise: Slavery and Freedom in British New York,” in Berlin, Ira, and Leslie M. Harris, eds. Slavery in New York. New York: The New Press, 2005.

- Maika, Dennis J. “The First Slave Traders in New York,” New York Almanack, September 28, 2002. https://www.newyorkalmanack.com.

- Manuscripts and Archives Division, the New York Public Library. (1796) Bowery Lane. Retrieved from

- https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/09ccb840-c6f2-0134-b944-00505686a51c

- Manuscripts and Archives Division, the New York Public Library. (1796) Matthew Buys land in five equal parts, on Bowery Lane. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e73bc7b0-c6f1-0134-8a0e-00505686a51c

- Medford, Edna Greene, ed. Historical Perspectives of the African Burial Ground: New York Blacks and the Diaspora. U.S. General Services Administration. https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/Vol3-HistoricalPerspectivesOfTheNYABG1.pdf.

- Meuwese, Mark. “Kieft’s War: Mass Murder on Manhattan,” New York Akmanack, July 20, 2022. https://www.newyorkalmanack.com.

- Moore, Christopher, “A World of Possibilities: Slavery and Freedom in Dutch New Amsterdam,” in Berlin, Ira, and Leslie M. Harris, eds. Slavery in New York. New York: The New Press, 2005.

- Mosterman, Andrea C. Spaces of Enslavement: A History of Slavery and Resistance in Dutch New York. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2021.

- New York City, Compiled Marriage Index, 1600s-1900s www.ancestry.com.

- New York Landmarks Commission. Noho Historic District Extension Designation Report., May 13th, 2008. https://media.villagepreservation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/15123023/NoHo-Historic-District-Extension-NYC-LPC-Designation-Report.pdf.

- New York Public Library. “‘NYC’s Early African American Settlements: New Amsterdam’s “Little Africa.’” https://libguides.nypl.org/nyc_early_africanamerican_settlements/new_amsterdam.

- New York State Archives. “New Exhibit: The Land of the Blacks.” https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Gallery/280.

- New York State Archives. New Netherland Council Dutch Colonial Patents and Deeds. https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/collections/5513.

- Pelletreau, William S. Early New York Houses. New York: Francis P. Harper, 1900. http://www.ancestraltrackers.org/ny/resources/early-new-york-houses-1900.pdf.

- Purple, Edwin R. Genealogy of The Provoost Family of New York. New York: Privately Printed, 1875. http://dutchgenie.net/GSBC-familyfiles/familyfiles/exhibits/genealogical_notes_of_the_provoost_famil.pdf.

- Purple, Samuel Smith. Index to the Marriage Records from 1639-1801 of the Reformed Dutch Church in New Amsterdam and New York. New York: Privately printed, 1890. https://archive.org/details/indextomarriager00purp/page/n29/mode/2up.

- Sharp, Lewis Inman. The Old Merchant’s House: An 1831/32 New-York Row House. Master of Arts Thesis, University of Delaware, 1968.

- Shorto, Russell. The Island at the Center of the World. New York: Vintage Books, 2004.

- Stokes, I.N. Phelps. The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909. 6 Vols. New York: Robert H. Dodd, 1915-28. https://archive.org/details/iconographyofman06stok/page/123/mode/1up?q=“Otto+grim”.

- U.S. and Canada, Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s. www.ancestry.com.

- Van Laer, Arnold J.F., Translator. New York Historical Manuscripts: Dutch. Volume I Register of the Provincial Secretary, 1638-1642. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1974. https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/files/6514/0151/8811/Volume_I_-_Register_of_the_Provincial_Secretary_1638-1642.pdf#page87.

- Van Laer, Arnold J.F., Translator. New York Historical Manuscripts: Dutch. Volume IV Council Minutes, 1638-1649. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1974. https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/files/9714/0152/0608/Volume_IV_-_Council_Minutes_1638-1649.pdf.

- Van Winkle, Edward. Manhattan 1624 – 1639. New York: Holland Society of America, 1916. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/19040/images/dvm_LocHist005578-00011-0?treeid=&personid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=jfo59&_phstart=successSource&pId=2000000000&rcstate=dvm_LocHist005578-00030-0:765,682,907,730;939,686,1109,732;1588,2083,1748,2129;1571,587,1779,636;2053,598,2175,644;2181,600,2319,649.

- Wall, Diana diZerega. “The Architectural Excavations at the Old Merchant’s House,” in Historic Structure Report, Volume 2, 1993. Merchant’s House Museum Manuscript and Archive Collection.

WEBSITES

- Black Gotham Experience: www.blackgotham.com.

- Netherlands National Archives: www.nationaalarchief.nl/en.

- New Amsterdam History Center: https://newamsterdamhistorycenter.org.

- New Netherland Institute: www.newnetherland.org.

- New York Slavery Records Index. https://nyslavery.commons.gc.cuny.edu.

- New York State Archives: archives.nysed.gov.

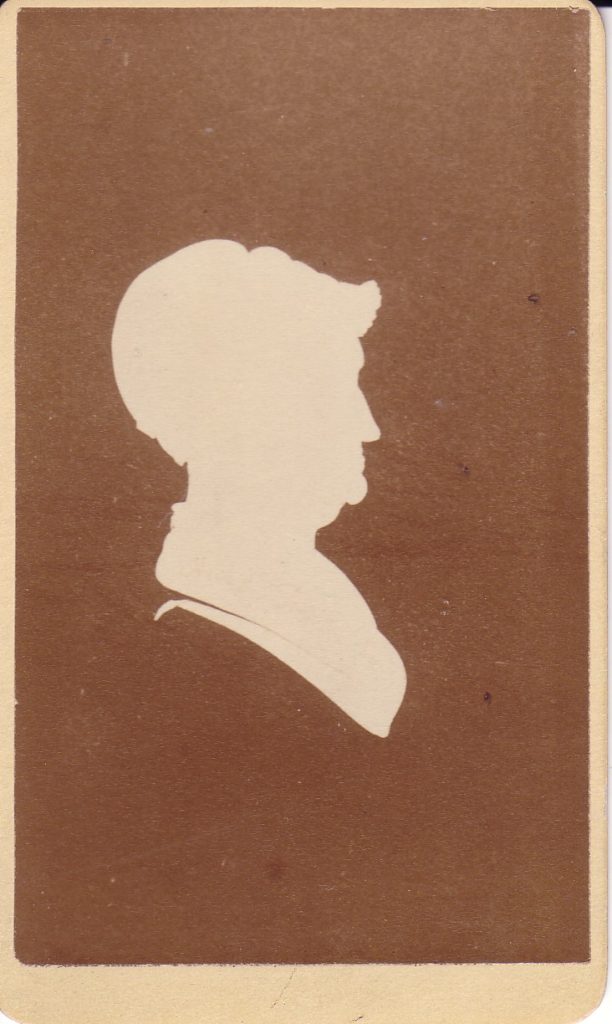

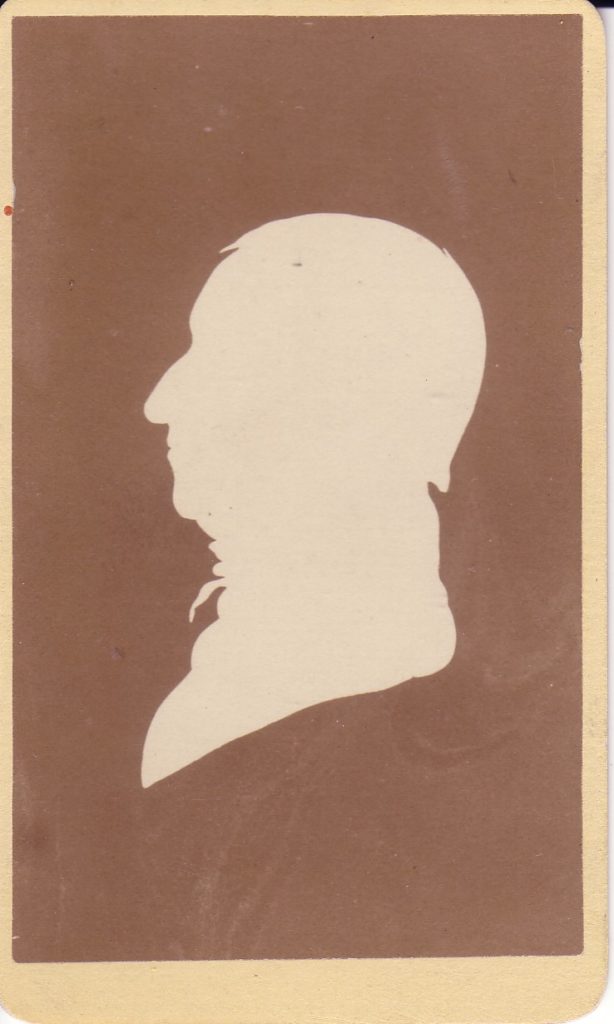

Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part 4 – The End of an Era

by Ann Haddad

..

On February 4, 1835, a notice appeared in the Shipping and Commercial List and New-York Price Current that the hardware firm of Tredwell, Kissam, and Company, which had flourished for over 20 years on Pearl Street, was “dissolved by mutual consent.”

That same year, Seabury Tredwell moved his family from their home on Dey Street, in lower Manhattan not far from the seaport, to a Late Federal/Greek Revival row house on Fourth Street, in the neighborhood then known as the elite “Bond Street area.” He was 55 years old, and not about to retire from the world. For 30 years until his death he maintained an active life, keeping pace with the enormous economic changes taking place in New York City and making shrewd investments in real estate, railroads, and natural gas. (For more information about Seabury Tredwell’s hardware business and investments, see Seabury Tredwell: The Merchant Years and Seabury Tredwell: Man of Opportunity). His years of hard work led to outstanding success and enormous wealth. Now we turn our attention to his final illness and death in March 1865.

..

..

..

Seabury’s Final Illness

For some years leading up to his death, Seabury’s attending physician was Dr. George E. Belcher (1818-1890), a practitioner of homeopathy, an alternative medical practice. Dr. Belcher had converted to homeopathy from conventional medical treatments in 1844. (For more information about homeopathy and the Tredwell family’s physicians, see my blog post of October 2016: The Doctor in the House is a Homeopath!). Seabury’s death certificate, signed by Dr. Belcher, states he died from acute kidney failure caused by Bright’s Disease, now known as acute or chronic nephritis (inflammation of the kidneys). The disease is characterized by a wide range of symptoms, including swelling, coma, stroke, convulsions, and blindness.

Seabury’s homeopathic treatment plan likely included the administration of herb and plant remedies, such as arsenicum, belladonna, burdock root, and juniper berry; dietary restrictions (no red meat, cheese, or alcohol); warm compresses and massage of the lower back for pain; and inhalation of lavender oil to reduce anxiety.

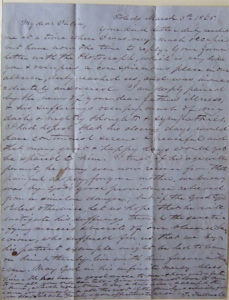

Although Dr. Belcher listed Bright’s Disease as the cause of death on Seabury’s death certificate, we do not know how long he suffered with the disease. According to a story related by his granddaughter Elizabeth Tredwell Stebbins (1885-1973), Seabury caught a cold after returning from his home in Rumson, New Jersey, by boat one winter’s day in 1865, which led to his death on March 7. On March 3, his nephew Timothy Tredwell, who lived in Toledo, Ohio, penned a letter to Seabury’s daughter Julia, after learning of his condition:

“I am deeply pained by the news of your dear father’s illness & his sufferings occupy much of my daily & nightly thoughts & sympathies… May god in his infinite mercy bless him. He has been a good uncle to me & how good a father to you all, you only can tell.”

The Civil War Draws to a Close

In early 1865, as Seabury’s life was coming to an end, the nation witnessed the collapse and death of the Confederacy. The Union Army, thanks to the brilliant military strategies of Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman, left the Confederate Army in tatters. Passage of the 13th Amendment at the end of January 1865 abolished slavery and on March 4, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as President for a second term in Washington, D.C. One month later, on April 9, the Civil War ended when General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

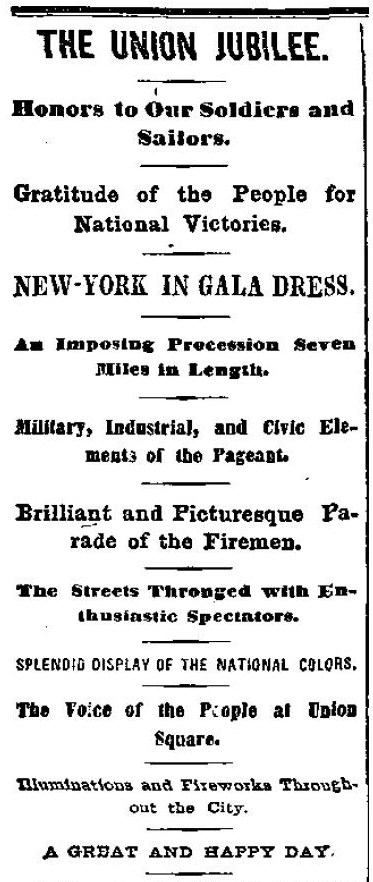

The Union Jubilee

On March 6, as Seabury lay on his deathbed, surrounded by his family, New York City joyously celebrated the anticipated end of the Civil War with a “Union Jubilee.” Over one million spectators lined the streets to see the grand parade, which included military troops; volunteer firemen; members of clubs, businesses, and community organizations; and even a menagerie of, among other animals, elephants and camels. John Ward, Jr., who was a National Guardsman and who lived near the Tredwells, on Thompson and Bleecker Streets, marched in the parade with his Company; the excitement of the event is palpable in his diary entry:

“Beautiful, perfect day. I put on my uniform and medal after breakfast & rigged the flag out of Mother’s window. …We formed in Washington Square….Tremendous crowd. Largest ever known. We wheeled well into Broadway, marched down to the Museum, up Park Row, etc., and Bowery to Union Square (where we saw the procession still passing down Broadway) up 4th Avenue, to 23rd Street, up Madison Ave. to 29th St…up to 33rd St. over to 8th Ave., down to Washington Square where we were dismissed. Flags & decorations were fine. …Dined. Then went to Union Square to see the fireworks. Great crowd. Splendid pieces. Change of rebel to loyal flag. “Sumter” “Bombardment of Fort Fisher,” “Monitor & Merrimack” etc. Rockets & balloons. Homes and clubs illuminated. Mother had gas all lighted.”

As the Tredwell family maintained their vigil at Seabury’s deathbed that day, they surely heard the commotion of the celebration, the pealing church bells, and the gun salute fired in Union Square to signal the start of the parade. It is hard to imagine them sharing in the immense relief and happiness of the citizens of New York City. And the no doubt unadorned Tredwell home on Fourth Street must have stood out sharply among its neighboring dwellings, for The New York Daily Herald reported on March 7:

“Looking at the houses, you beheld one, grand continuous exhibition of flags from windows, poles, awnings, and every point whereon to hang this badge of loyalty and nationality. All of the hotels and public buildings were covered with the Stars and Stripes, and many houses displayed mottoes and inscriptions of an appropriate character.”

|

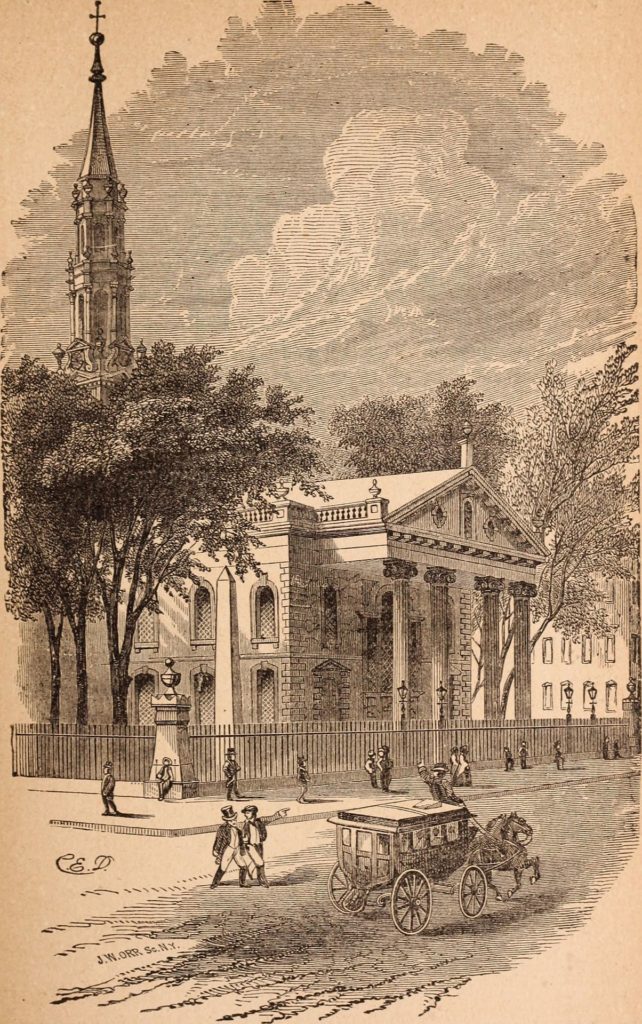

Death of the Patriarch

The day after the “Union Jubilee,” on March 7, Seabury died at the age of 84. His wife, Eliza, their eight children, and five grandchildren, survived him. After being waked in the front parlor for three days, on March 11 (a “beautiful, bright cold day,” according to John Ward, Jr.), Seabury’s funeral took place in the double parlor of his home, and he was interred in the New York City Marble Cemetery on East Second Street. On December 28, he was moved to his final resting place in the family plot in Christ Church Cemetery in Manhasset, Long Island.

A Family, and a Nation, Mourn

Eliza Tredwell and her family were approximately one month into their mourning period for Seabury when the American Civil War ended on April 9, 1865. Five days later, on April 14, President Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, and the glory of the Union victory was instantly forgotten, as the City plunged into mourning. Philip Hamilton Hill (1839-1915), a 27-year-old York City dry-goods clerk, noted the tragedy in his diary on April 15:

“Was horrified on waking this morning, to hear that President Lincoln was assassinated last night at Ford’s Theatre, Washington, by a man supposed to be J. Wilkes Booth the actor, and that an attempt had been made, upon the life of Sec’y Seward. Business was at a standstill all day, many of the Stores being closed, and most all draped in mourning, and a feeling of intense excitement existed throughout the City.”

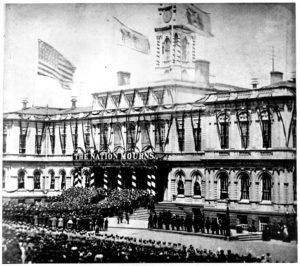

On Tuesday, April 25, Hill recorded in his diary how he joined the crowd (over 150,000 mourners) which lined up outside City Hall, from which hung a banner reading “THE NATION MOURNS,” to view the late President’s body, and the somber mood as Lincoln’s funeral cortege passed through New York City:

“By dint of hard work, and a good deal of tight squeezing, I managed to get through. I wouldn’t go through the same crowd again for ten dollars…The remains lay at the door of the Governor’s room, surrounded by a guard of honor…He looked the same as in life, with the exception of his skin, which was of a much darker hue….At 1 P.M. all the stores were closed, and the funeral procession commenced to move up Broadway towards the train on the Hudson River road which was to convey the remains West. Had our room full of company to view the procession.”

One wonders if any of the Tredwell family joined Hill at City Hall to view the President’s remains. They most likely joined the half a million New Yorkers who viewed the funeral procession, as it made its way up Broadway past Fourth Street. Even in their mourning attire, they would not have stood out in the crowds, for on that day many women donned widow’s weeds, and the men wore black crepe armbands, as a sign of their grief over President Lincoln’s death.

A Long Mourning Period

Mourning, the personal expression of loss and grief, was considered women’s work in the 19th century. Men, as the breadwinners who had to return to the workforce, were not expected to remain at home and follow the societal restrictions required by mourning etiquette. They donned a black hatband or armband and resumed their regular life. It fell to the women of the house to conform to social norms, by donning black mourning attire, sharply curtailing their socialization, and following the other precise rules of mourning frequently found in popular household manuals. The ability to follow elaborate mourning rituals was also a subtle indication of the wealth, respectability, and social status of the family; mourning attire and its accoutrements were expensive.

For Eliza Tredwell, mourning and all its associated traditions became a daily part of her life, perhaps for the remainder of her life. Typically, a widow in “full” or “deep” mourning adhered to a strict dress code of dull black for a year and one day, then proceeded, in the ensuing nine months to one year, to “half-mourning,” in which some colors, such as gray, white, mauve, and lavender, were permitted.

For much more information about mid-19th century mourning customs, please visit our exhibition “Death, Mourning, and the Hereafter in Mid-19th Century New York,” on view from September 26 to November 4. As part of the exhibition, visitors may meet Mrs. Tredwell in the front parlor and offer their condolences every Saturday afternoon in October from 1:30-3:30 p.m.

The End of an Era

An obituary in the New York Post on March 11, 1865, noted Seabury’s death:

“Among the deaths noticed in our column today is that of one of our oldest and most respected merchants, Seabury Tredwell. He was a gentleman of the old school, dignified and accomplished in his manners and high-minded and honorable in all his transactions…“He now goes out from us, one of the last of his generation, honored, respected and beloved by all.”

Sources:

- Hill, Philip Hamilton. Diaries, 1855-1865. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Knapp, Mary L. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- New York Daily Herald. March 7, 1865, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/17/19.

- New York Evening Post. March 11, 1865. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/9/19.

- New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1759-1949. www.familysearch.org.

- Merchant’s House Museum Archives. Tredwell, Timothy. Manuscript Letter, March 3, 1865. MHM 2002.4601.32.

- Shipping and Commercial List and New-York Price Current. February 4, 1835, p. 3. America’s Historical Newspapers, via ProQuest. Accessed 6/29/17.

- Spann, Edward K. Gotham at War: New York City, 1860-1865. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 2002.

- Strausbaugh, John. City of Sedition: The History of New York City During the Civil War. New York: Twelve Hachette Book Group, 2016.

- Ward, John. Diaries, 1847-1888. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part 3 – Man of Opportunity

by Ann Haddad

An Astute Businessman

George Chapman, who founded the Merchant’s House Museum in 1936, named it “The Old Merchant’s House” as a tribute to the early 19th century merchants who were known as the old merchants, among them Seabury Tredwell, who built New York City into the “commercial emporium of America” (as was said in the 19th century). However, Seabury Tredwell’s occupation certainly did not define him. Although he was a New York City hardware merchant (and a very successful one: see my post Seabury Tredwell, Part 2 – The Merchant Years), he did not confine his business interests to his Pearl Street warehouse and to life on the seaport. Rather, Seabury held a progressive view of the city and the nation’s capacity for growth; beginning in 1816, he began to invest in real estate, an interest that would continue until his death. As his career flourished, he purchased properties in Manhattan and Brooklyn, as well as further afield in North Carolina and Michigan. Seabury also kept abreast of the country’s industrial development, investing in the burgeoning railroad and coal gas companies.

New York on a Grid

Relatively early in his career (and just one year after taking on his nephew as a business partner), Seabury Tredwell started investing in the New York City real estate market. No doubt he was influenced and guided by two of his older brothers, Adam and John, who had moved to the city several years before Seabury, and who, by the first decade of the 19th century, owned extensive real estate in New York City and Brooklyn City. Seabury’s real estate investing involved him in one of the most important chapters of New York City history: the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, which called for the reorganization of Manhattan’s haphazard landscape into streets and avenues in a rectilinear grid pattern. Seabury’s first real estate purchase indicates that he was very likely aware of the Commissioners’ Plan. Probably eager to profit from the city’s anticipated growth patterns, in May 1816, prior to his marriage and while living in a boarding house, Seabury purchased a substantial three-lot parcel on the northwest corner of what is now 12th Street and Broadway, for $1,860.

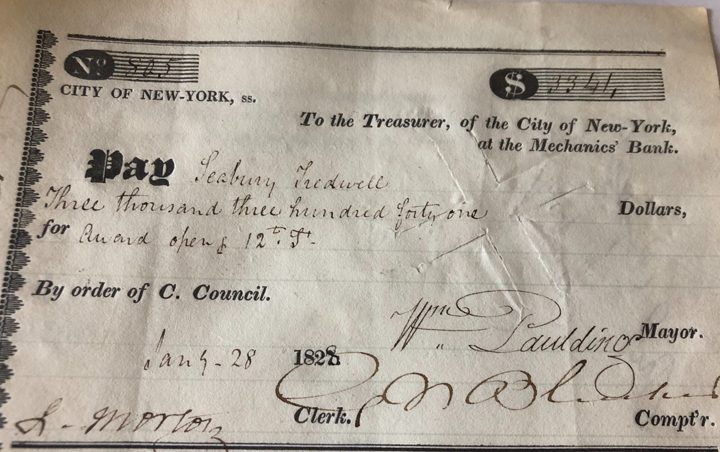

The City Pays

In 1826, ten years after Seabury purchased the property, New York City was preparing to open 12th Street; the first step of the process was to compensate all the property owners whose land would be claimed and used. According to the Minutes of the Common Council, on January 28, 1828, the city paid Seabury $3,341 for one lot of his property that was consumed by the grid. Nine other property owners also received payment.

Harlem Land

In December 1828, Seabury sold one of the remaining lots on 12th Street and Broadway to Michael Floy for $800, in exchange for 4 lots on 128th Street and 4th Avenue, in Central Harlem. Floy, a noted horticulturist, likely wanted the land to add to his already existing greenhouse south of what is now Union Square. The land in Harlem was a developing area, ideal for real estate speculation. Further research is required to determine if and how Seabury built on and profited from the Harlem investment.

A Wise Investment

Seabury sold the last lot on the property on 12th Street in February 1833 for $1,500. Seabury gained usable land in Harlem and realized a total profit of $5,641 from his original investment of $1,860.

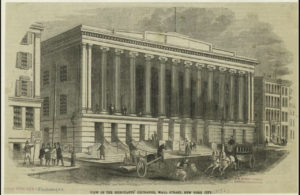

The New York Merchant’s Exchange

In addition to his personal real estate dealings, Seabury bid at auction for some of his properties at the New York Merchant’s Exchange, located at 55 Wall Street. Built in 1836-42, it replaced the original Exchange, which was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1835. The Exchange housed a post office, banks, and the Chamber of Commerce, as well as rooms for auction sales of real estate and stocks, which was at a fever pitch as the city growth pushed northward, and housing was in great demand to accommodate the exploding population.

According to the records of New York Merchant’s Exchange of July 17, 1856, Seabury purchased at auction a lot on the southwest corner of 8th Avenue and 53rd Street, for $4,050.

Seabury Bets on Brooklyn

When Seabury ventured into the frenzied Brooklyn real estate market in the mid-19th century, Brooklyn was the third largest city in America (it didn’t merge with New York City until 1898), and soon to become one of America’s major industrial centers, due to its location on the East River, which allowed for convenient transportation of materials and manufactured goods. Beginning in 1814, regular steam ferry service between Fulton Street in Brooklyn and Beekman Slip (now Fulton Street) in Manhattan, made it easy for affluent families who had moved to Brooklyn, as well as workers with jobs in the city, to commute back and forth.

.

.

Before It Was DUMBO

Seabury no doubt was aware of Brooklyn’s changing character and landscape when he acquired his first piece of Brooklyn property in March 1852, when he purchased, from the estate of his brother John, four plots on Fulton and Pearl Streets in the Second Ward, for $12,875. This area, located along the East River waterfront, is now known as the DUMBO Historic District (an area now bounded roughly by the Brooklyn Bridge, the East River, York, and Navy Streets). Although this area was one of the first residential-use sections of Brooklyn, by 1852 it was well on its way to becoming a major manufacturing center, with factories, foundries, and warehouses vying for space with two and three-story residential houses. Two ferry lines, one right at the foot of Front Street, made regular trips to and from New York City.

In 1853, Seabury sold this property for $15,500. In one and a half years, he made a profit of $3,500.

… and Fort Greene

In 1858 and 1859, Seabury added to his Brooklyn holdings with the purchase of nine lots, some with buildings, on Fulton Avenue, Raymond Street, and Navy Street, in the 11th Ward (now the Downtown Brooklyn/Fort Greene area), for $12,000. The property was advertised in the Evening Post in 1850 as being “located in the most desirable part of Brooklyn, being in the immediate vicinity of Washington Park, which is now being regulated and graded.” He immediately sold two of the lots for $4,600. In 1863, he sold four of the lots for $15,500, making a profit on land he had owned for only four years.

With the growth of middle-class residential districts, including Fort Greene, house construction in Brooklyn skyrocketed. Row houses appeared almost overnight on the quiet streets, and became ideal homes for professionals who commuted to their New York City businesses. According to Seabury’s personal ledger, he spent a great deal of money building on his Brooklyn properties. Between July and October 1863, for example, he paid John P. Seeley (a “master builder,” according to the 1860 Federal Census) $9,370, most likely for house construction. Seabury also paid $102.31 to have a sidewalk laid on his property on Raymond Street.

The Good Son-in-Law

Effingham Nichols, an attorney and the husband of Seabury’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth, must have been influential in Seabury’s decision to invest in Brooklyn real estate. He lived in Fort Greene with his wife and daughter, Lillie, from 1859 to 1864, and had begun to buy property there in 1851; by 1859 he owned at least seven properties in the neighborhood. (See my post of April 2017, “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing”). In addition, one of his brothers, William B. Nichols, owned houses near Seabury’s property on Fulton Avenue and Raymond Street. Effingham may have collected rents for Seabury, and may even have acted as an agent for him, buying and selling properties at his discretion. Records in Seabury’s personal ledger indicate that Seabury provided Effingham with funds to repair the Fulton/Raymond Street property. In 1863, for example, he gave Effingham $63.84 for sewer work.

In 1863, Seabury made what may have been his last purchase of Brooklyn real estate, bidding at auction for another parcel of land in Fort Greene, paying $4,400. The Land Conveyance Records Index for Kings County indicate that Seabury purchased at least three other properties in Brooklyn; the details of these purchases could not be determined because the conveyance records are missing.

Seabury the Landlord

Seabury also collected rents on some of his properties. In 1862, he rented three buildings on Fulton Avenue to Mary Louise Tredwell (a distant cousin) for $1,200/year. Seabury’s personal ledger indicates that in 1852 he was collecting rent of $1,000/year on a factory on Front Street, and $212.50/year for a Pearl Street property.

Seabury also engaged in seller financing, wherein he financed purchases of his property to individuals, rather than have them obtain a bank mortgage. In his personal ledger, he listed several individuals to whom he sold property, such as John and William Healy, John Rupp, and John David, and the amounts of the mortgages he granted.

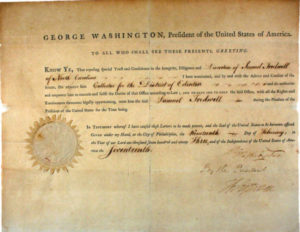

Ventures Further Afield

Records show that Seabury also invested in commercial property with his partners for their business. Seabury and his nephews likely decided to invest in real estate in North Carolina due to their business dealings there and their familiarity with the state. Seabury’s eldest brother, Samuel Tredwell (1763-1827), had been a prestigious figure in North Carolina after the Revolutionary War. In 1785, Samuel moved to Edenton, North Carolina, whose vital port was the second largest in the state. In 1793, he was appointed Collector of the Port of Edenton by President Washington, a position he held until his death. He also served as State Commissioner of North Carolina in 1818.

In 1835, Tredwell, Kissam & Company purchased 13,000 acres of North Carolina swampland from Charles Johnson for the purpose of harvesting lumber to make shingles. A North Carolina Supreme Court case in June 1840 involved a lawsuit brought against a trespasser who was using the land illegally. At this time it is unknown when and to whom Seabury sold the land.

In the Transactions of the Supreme Court of the Territory of Michigan, 1825-1836, there is a record of a court case involving Tredwell, Kissam & Company in a lawsuit against three men, Isaac Otis, George Walker, and John Hale. The nature of the suit is unknown.

The Children Benefit

A portion of the original property on Fulton Avenue and Raymond Street in Brooklyn was still under Seabury’s name upon his death in 1865, and became part of his estate. His children benefited from Seabury’s real estate savvy. In 1902, Samuel Lennox, his younger son, who had purchased the Fulton Avenue property from his father’s estate some years earlier, sold it for $40,200. The property was described in a February 1902 advertisement in the Brooklyn Eagle as “being a very valuable plot with three two story and cellar brick buildings thereon, with 5 stores therein.”

Seabury’s Investment Portfolio

It is unclear when Seabury set about building an investment portfolio, but by his death in 1865 he had amassed enough stock to significantly cushion his family’s inheritance. Getting in on the ground floor of both the steam engine and lighting revolutions taking place in New York City and elsewhere, he invested heavily in various railroad stock (including the New York and Erie Line, the Hudson Line, Chicago and Rock Island lines, and Hartford and New Haven lines) and in gas lighting. Seabury may have consulted his friends and former colleagues in the business world for advice; he also may have looked to his sons-in-law Effingham Nichols and Charles Richards for guidance in choosing his investments.

The New York and Erie Railroad Line

Seabury Tredwell was an early investor – and possibly one of the original investors – in the New York and Erie Line, a railroad that linked Erie Canal towns directly to New York City, allowing for faster transportation of lumber and agricultural goods. Leading merchants of the day, as well as land investors and bankers, were granted the charter in 1832, creating a railroad line that ran west from the Hudson River in Piermont, New York, to Dunkirk on Lake Erie. This proved to be a risky investment through the years, however; the railroad went bankrupt several times, and became known as “the scarlet woman of Wall Street,” due to the financial shenanigans of men like Jay Gould and Cornelius Vanderbilt, who vied for control of the railroad and manipulated the company holdings to their own advantage.

Take the Hudson River Line

The Hudson River Line was another of Seabury’s investments. In 1846, 11 years after Seabury sold his business, the Hudson River Line was chartered. This commuter line initially ran from Chambers and Hudson Streets in lower Manhattan up the West Side via horse cars (steam trains were not permitted below 30th Street) to a depot at 32nd Street, where the horses were exchanged for steam engines, then along the east side of the Hudson River, to Peekskill. By 1851 it had been extended to Poughkeepsie, which remains its terminus. Through a connection with the Troy and Greenbush Railroad, it provided a link between Albany and lower Manhattan, a trip of less than four hours. A similar journey by steamboat took over seven hours! One imagines that the growth of the railroad industry (with its speed, efficiency, and convenience) and its revolutionary impact on 19th century life was not lost on Seabury, who, like everyone else, had previously relied on the comparatively snail-paced omnibuses, ferries, and coaches.

New York Gas Light Company

Seabury’s personal ledger indicates that he owned 133 shares of stock in the New York Gas Light Company, the first coal gas company in New York, founded in 1823. One wonders if he was one of the original investors in the company, which first focused on street lighting, servicing Manhattan south of Canal Street. Ultimately six gas companies supplied gas for illumination and later, for heating and cooking. The competition for customers was so fierce in the growing city, that workers from different companies would do battle in the streets over the installation of gas mains; known as “gas house gangs.” In 1884, the companies merged to form Consolidated Gas Company (now known as Con-Edison).

More than a Merchant

Now that Seabury’s varied business interests have come to light, and we see the extent to which he ventured into unchartered investments, it is clear the title “merchant” doesn’t embrace all that Seabury was in the business world of the 19th century. Seabury Tredwell, along with many of his peers in the merchant class, were men of opportunity who shaped the economic future of New York City. Perhaps we should consider renaming the Merchant’s House — the “Investor’s House”? The “Risk-Taker’s House”? What do you think?

Sources:

- Blume, William Wirt, ed. Transactions of the Supreme Court of the Territory of Michigan 1825-1836, Volume II. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1940. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 5/29/19.

- Bristed, Charles A. The Upper Ten Thousand: Sketches of American Society. New York: Stringer and Townsend, 1852. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 6/5/19.

- Brooklyn Citizen. April 2, 1902, p. 9. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 5/3/19.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 22, 1902, p. 15. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 5/3/19.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Conveyances, 1724-. New York Land Records, 1630-1975. Images. familysearch.org.

- “Erie Railroad Company.” Encyclopedia Britannica. www.britannica.com. Accessed 6/3/19.

- Evening Post. October 5, 1850, pg. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 5/22/19.

- “History of Con Edison.” American Oil & Gas Historical Society. www.aoghs.org. Accessed 6/3/19.

- Koeppel, Gerard. City on a Grid: How New York Became New York. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2015.

- Lockwood, Charles. Manhattan Moves Uptown: An Illustrated History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1976.

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. DUMBO Historic District Designation Report. December 18, 2007. www.neighborhoodpreservation.org. Accessed 5/21/19.

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Fort Greene Historic District Designation Report. September 26, 1978. www.home2.nyc.gov. Accessed 5/22/19.

- New York Daily Herald, March 11, 1865, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/9/19.

- North Carolina. Supreme Court. North Carolina Reports: Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of North Carolina, [v 023, June Term 1840-June Term 1841]. State Library of North Carolina. www.digital.ncdcr.gov. Accessed 5/29/19.

- Notes from Seabury Tredwell’s Personal Ledger Book. Merchant’s House Museum Archives.

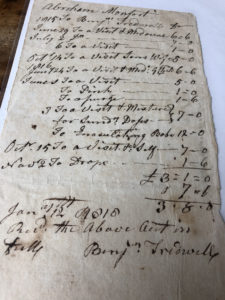

Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part 2 – The Merchant Years

by Ann Haddad

A Knack for Success

Throughout his life, Seabury Tredwell had a remarkable knack for being in the right place at the right time. Or perhaps he had wise advisors who guided him carefully. However he made his decisions, they seemed to always be the right ones. He arrived in New York City to make his fortune as its wealth and reputation as a great commercial center was about to explode; thirty-five years later, he ended his mercantile career and moved uptown, narrowly escaping the Great Fire of 1835 and the economic Panic of 1837. He knew the chic neighborhood to move to and the finest country property to buy. The story of his trajectory from country farm boy to elite New York merchant is a classic success story.

Enter Seabury

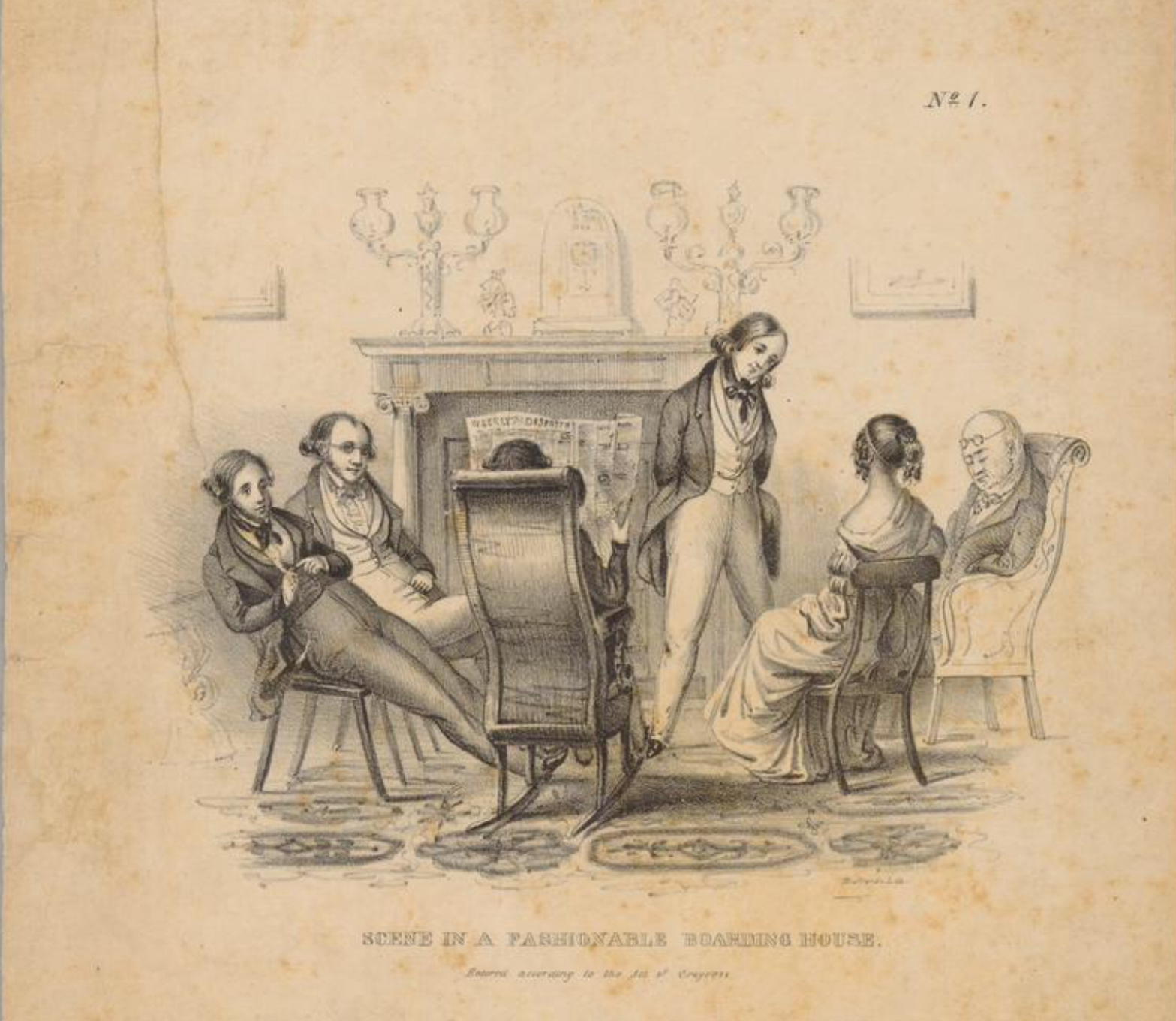

Seabury arrived in New York City sometime around 1800, when the city’s population was approximately 60,500. Probably working initially as an entry-level clerk, he became one of approximately 1,100 merchants who aspired to achieve success in the growing city. He either lived with his boss (clerks often slept on the store premises), or took lodging in a boarding house. He most likely packed all of his possessions into one trunk; its contents may have been similar to that brought by a young clerk in “The Perils of Pearl Street,” : “Two pair of stockings, one vest, one pair of pantaloons, one dress-coat, two nightcaps, three cravats, one pair of boots, and one pair of slippers.” No doubt Seabury was given a sum of money by his father or another relative to tide him over financially until he was self-sufficient. For more information about Seabury’s arrival in New York City, see Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part I – The Early Years.

“The Commercial Emporium of America”

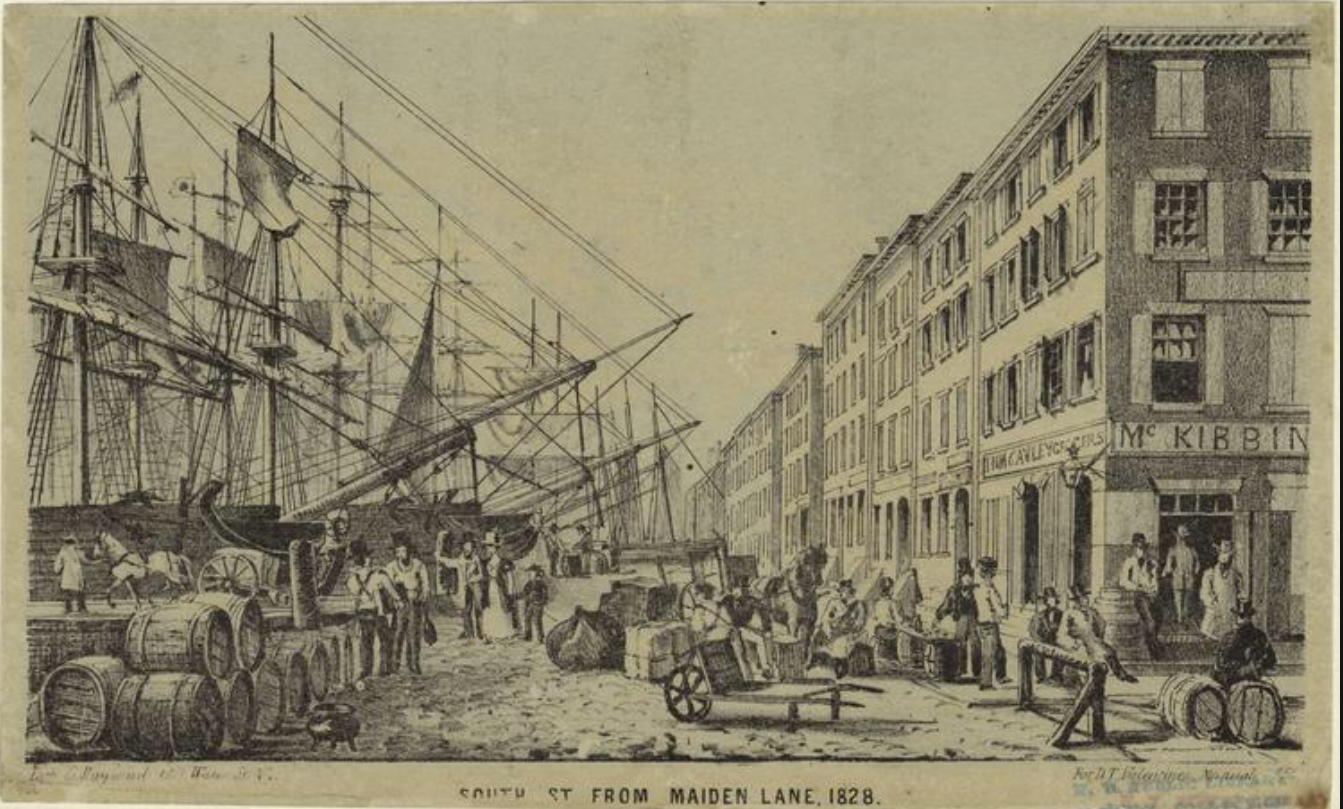

With the end of the War of 1812, the lifting of British blockades, and the subsequent restoration of trade, the Port of New York began the steady economic growth that eventually led it to become the world’s busiest seaport. According to The Rise of New York Port (1939), the years from 1815-1865 saw the seaport’s greatest development into “the commercial emporium of America.” Several factors contributed to this intense and rapid growth.

The Black Ball Line

The launching of the Black Ball Line in 1818, whose four ships made regularly scheduled voyages to and from Liverpool, allowed New York to ramp up its importing of foreign goods, beating out the competitive port cities of Boston and Philadelphia. On average the packets travelled from New York to Liverpool in 23 days; the reverse trip west could take anywhere from 45 to 90 days, depending on weather and wind conditions. Due to the success of the Black Ball, other lines soon followed suit and, according to Gotham (1999) by Burrows and Wallace, by 1838 52 packet ships were shuttling from New York to Liverpool. The development of inland steamboat service by 1817 also contributed to traffic between the city and Long Island Sound and the North (now Hudson) River. Imagine the East and North River wharves lined daily with nearly 1,000 steamboats and packets!

An Ideal Harbor

The joining of the East and North Rivers created a large harbor that was ideal for foreign and domestic commercial trade. Owing to its location and tides, the harbor was well sheltered and free of the treacherous ice that could damage ships, and therefore its ports were accessible in all seasons. The depth of the water allowed large ships to come close to the wharves to load and unload cargo.

The Erie Canal – “Clinton’s Ditch”

The opening of the 363-mile Erie Canal in 1825, which connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes via the Hudson River, galvanized commerce and enabled New York to become the gateway to the rich agricultural resources of the Midwest. Those who opposed the plan to build the canal referred to it as “Clinton’s Ditch,” to ridicule Governor DeWitt Clinton, who was one of the major supporters of the project. Its route from New York City to Buffalo allowed midwestern markets to receive highly desirable imported manufactured goods; in return, domestic produce grown in the nation’s interior could be shipped (at a dramatically lower cost) to the New York markets. This exchange of more and more goods took significantly less time, increasing the velocity of trade in New York dramatically.

As a result of the surge and speed of trade, a new way of doing business developed in New York. Merchants sought ways to store the wealth of goods coming in and going out, while also selling them directly to consumers. The brick warehouses constructed for this purpose, which forever altered the landscape of Lower Manhattan, typically held a store/living space on the ground floor with storage areas above. The ubiquitous cart man transported the goods from the teeming wharves to the shops, where they would be hauled up by ropes to the second and third floor.

The Merchant Class

As New York’s commercial activity accelerated with each passing year, the wealth of the city and its merchants grew to unprecedented heights. According to the Commercial Directory (1823), in 1820 the value of goods imported into New York City was $26 million, and the value of exported foreign merchandise and domestic goods was nearly $12 million. The men who controlled the mercantile business became powerful and wealthy in the process and were known as the elite “Merchant Class.” Individually, those who could claim membership in this group were later referred to as “Merchant Princes.” Seabury Tredwell was indeed deserving of this distinction.

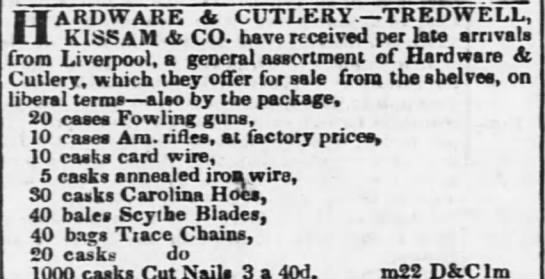

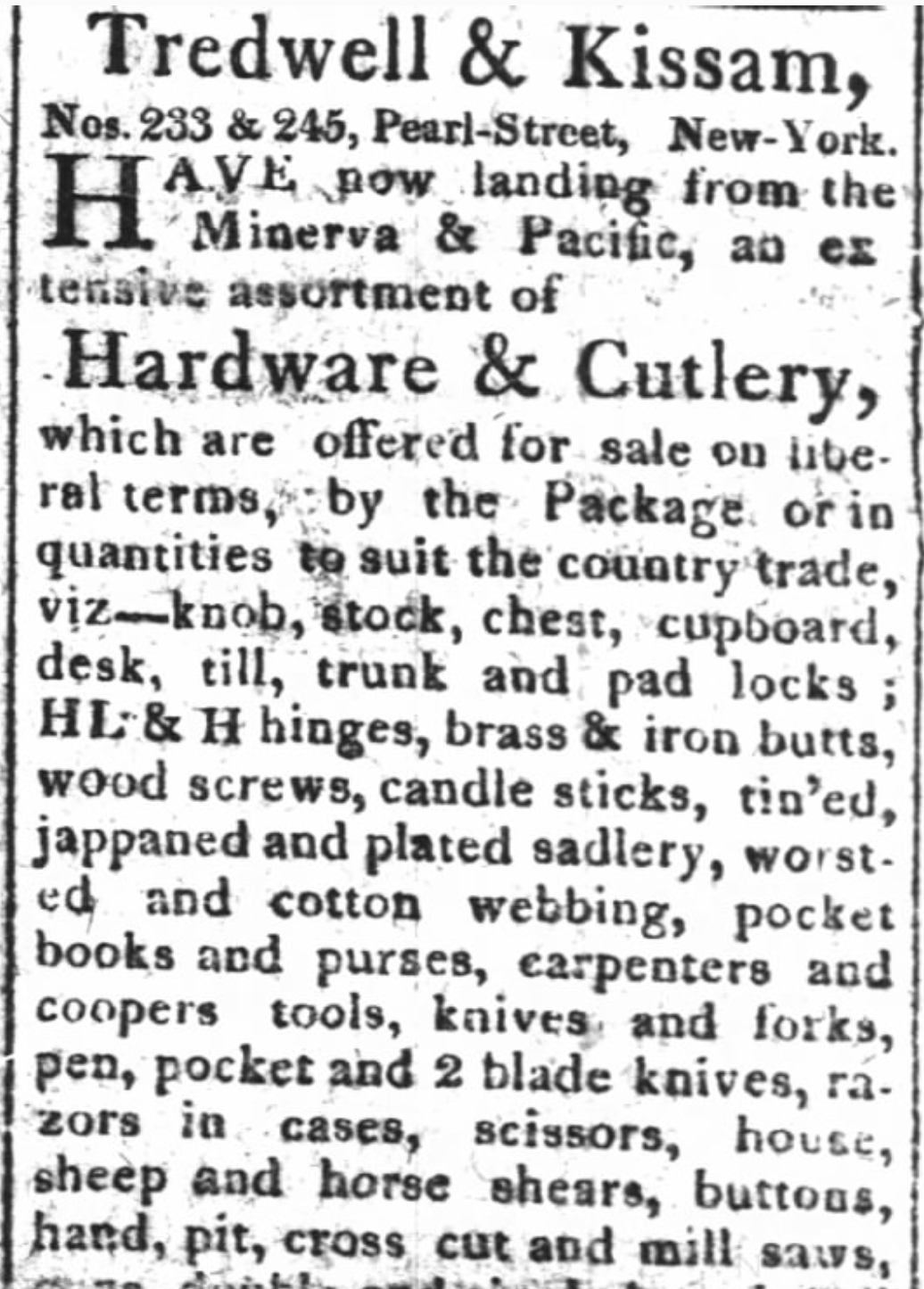

The Hardware Trade: Seabury’s Niche

We do not know if Seabury was set on becoming a hardware merchant from the start, or if he clerked for a merchant in the hardware trade, during which time he learned the details of the business. According to John C. Tucker, a New York City hardware merchant whose career overlapped with Seabury’s for several years, in the first half of the 19th century, “American Hardware was almost unknown.” Seabury purchased his goods from importers and wholesaled them from his warehouse. During his years in the hardware trade, more than 85 percent of the goods Seabury sold were imported. According to Tucker, the only American-made hardware was cut nails, and even those Seabury’s company also imported (see advertisement at right). Hence Seabury and other businessmen relied heavily on the merchant ships to deliver their goods in a timely fashion. Severe weather or a shipwreck could be a major setback to business.

It should be noted, however, that some percentage of the goods Seabury sold were American-made. At the bottom of an Evening Post advertisement (September 6, 1816), he added, “ALSO, Many articles of American Manufacture in the Hardware line.”

Trade Embargo

From his shop and warehouse on Pearl Street (see previous post for shop locations), Seabury set to work building his business and reputation as a hardware merchant. His career may have been derailed for several years during the trade embargo imposed by President Thomas Jefferson from December 1807 to March 1809, which prohibited American ships from trading in foreign ports. As a result of this effort to protect American shipping rights and to maintain neutrality amidst the raging Anglo-French conflict, activity at the seaport came to a standstill. The export trade declined by nearly 80 percent; imports by 60 percent. Many mercantile firms went out of business and unemployment among seaport workers skyrocketed. The embargo may explain the absence of Seabury’s name from the city Directory in 1808; like many other merchants, he may have had to close his business. Once the Embargo Act was repealed by Congress, in March 1809, Seabury’s name once again appeared in the Directory.

All in the Family

According to hardware merchant John C. Tucker, a “large business” was one that sold between $150,000-$200,000 worth of goods per year. Although the size of Seabury’s business is unknown, by 1815 his wealth had grown to such an extent that he took on his nephew, Joseph Kissam, as a partner, naming the firm Tredwell & Kissam. Joseph’s brother, Samuel, would join them three years later; the firm then became known as Tredwell, Kissam, and Company, and remained so until Seabury’s retirement in 1835. The partners typically shared equally in the responsibilities and profits of the company.

In The Old Merchants of New York (1863-66), author Joseph A. Scoville notes that bringing family members into the business was almost de rigueur. A merchant on the road to success “does not rest until one by one he has procured situations for all of his brothers” (or in Seabury’s case, nephews). Joseph (1790-1863) and Samuel (1796-1856), were the sons of Seabury’s sister, Elizabeth (1767-1803), and her husband Dr. Daniel Whitehead Kissam (1763-1829), of Hempstead, Long Island.

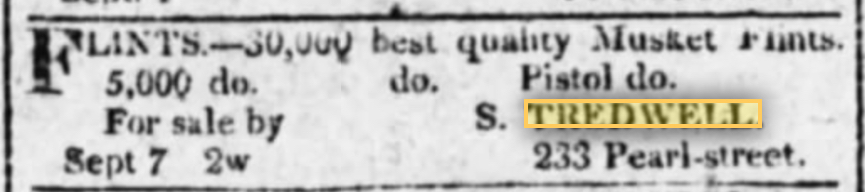

Newspapers: The Way to Advertise

Although they did some some retail business in the stores attached to their warehouses, (Seabury’s advertisements occasionally indicated that items may be purchased “from the shelves”), companies like Tredwell, Kissam and Company worked largely in wholesale. To keep his customers apprised of the goods arriving from England, Seabury advertised in the newspapers, paying a subscription of $40 per year to advertise at will, but typically three or four times a year, based on the packet schedule. (According to The Old Merchants of New York, “no respectable house would overdue the thing. [over-advertise]”). Country merchants, who would come into town several times a year to make their purchases (typically in the spring and fall), consulted the advertisements to determine which houses to visit. With these personal interactions, merchants would establish relationships with their clients, and come to understand their financial situations; this usually ensured customer loyalty, especially if the merchant extended credit to the customer when necessary.

Seabury Tredwell’s first newspaper advertisement appeared on September 7, 1812. He advertised 30,000 musket flints (a form of quartz used to ignite firearms), and pistols. Tredwell & Kissam’s first advertisement appeared on August 16, 1816. As this was one year after Seabury took on a partner, it may indicate a deliberate decision on Seabury and Joseph’s part to expand the scope of their business. The ad boasts of the company’s “extensive assortment” of goods, and stress that they offer “liberal terms” for both retail and wholesale “by the package, or in quantities to suit the country trade.” In addition to hardware such as cutlery, waffle irons, tools, and cookware, the company also sold looking glasses, buttons, and ladies’ pocket books.

Newspapers like the Evening Post also regularly printed notices of ships’ arrivals in New York Port. On November 2, 1815, the ship Zodiac arrived after a 70-day voyage from Liverpool, England, bearing cargo for Tredwell & Kissam. These notices would then typically be followed by advertisements from the company announcing the goods they now had in stock.

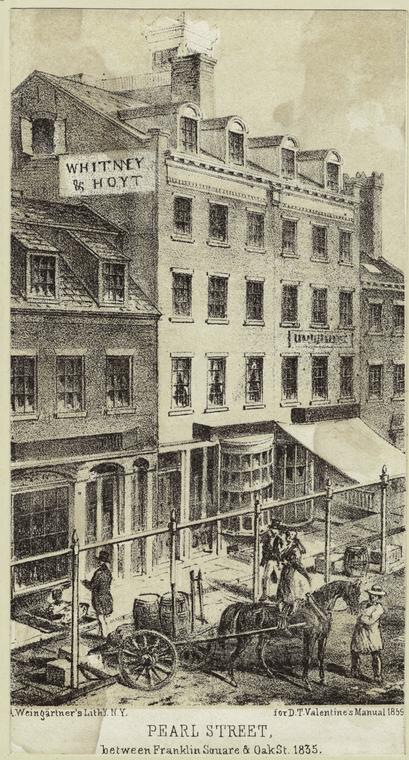

A Pearl of A Street

Prior to the Civil War, the mile-long stretch of the East River from the Battery to Corlear’s Hook (now at Cherry Street and the East River Drive), was home to the busiest wharves. Because of their proximity to the waterfront, where ships loaded and unloaded their cargo, streets such as Pearl, (especially the blocks north of Wall Street and south of Fulton), Front, South, Wall, Pine, and lower Broadway comprised the epicenter of commercial activity. Hundreds of merchants had their shops and warehouses on these streets. According to the Commercial Directory (1823), on Pearl Street alone, 90 mercantile firms vied for customers, selling everything from dry goods and cotton to china and fine jewelry. Auction houses were plentiful as well. Tredwell, Kissam and Company was one of eight hardware merchants on Pearl Street that year.

Seabury’s Daily Routine

Whether he ventured to his warehouse on Pearl Street from his boardinghouse a short distance away, or later from his home on Dey Street, when he had to walk a few blocks further, Seabury’s daily routine probably resembled the one described in The Old Merchants of New York:

“To rise early, to get breakfast, to go down to the counting house of the firm, to open and read letters – to go out and do some business…until twelve, then to take a lunch and a glass of wine at Delmonico’s; or a few raw oysters at Downing’s; to sign checks and to attend to the finances until half past one; to go on change [the Merchant’s Exchange]; to return to the counting house, and remain until time to go to dinner, and in the old time, when such things as packet nights existed [when the packet ships would arrive at port], to stay down until ten or eleven at night, and then go home and go to bed.”

Rising Stars

Tredwell, Kissam, and Company achieved great success in the hardware business. From their early days, they cast a wide net to acquire customers. Records indicate that, in addition to New York, they did business in Connecticut, Philadelphia, Massachusetts, and Michigan.

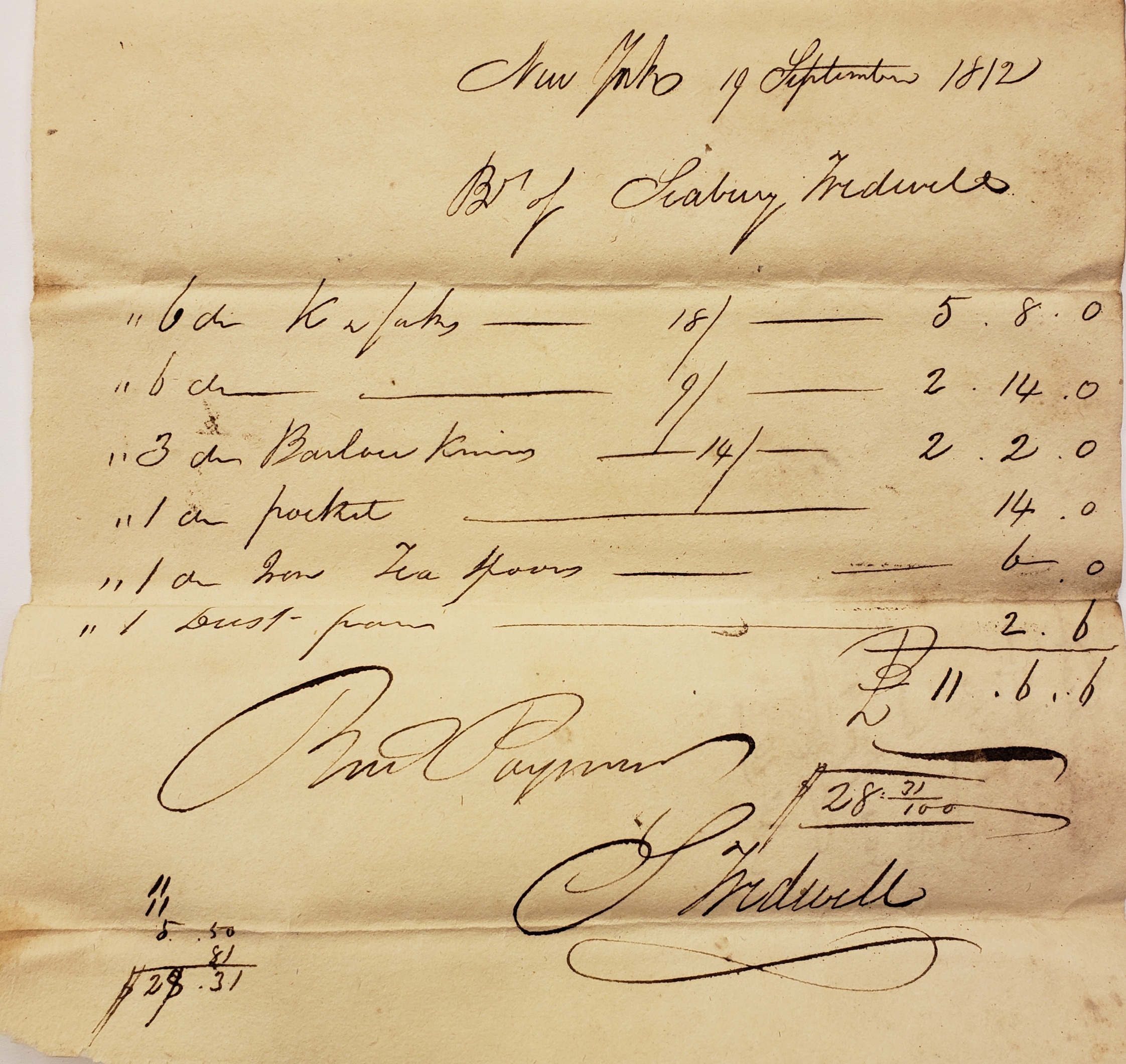

On September 19, 1812, a storekeeper in New Milford, Connecticut, named Elijah Boardman paid $28.31 to Seabury Tredwell for goods, including “three dozen barber knives, 1 dozen teaspoons, and 1 dozen dustpans.”

Another undated bill of $3.56 to Elihu Harrison of Morris, Connecticut, from Tredwell, Kissam, and Company, was for “steel knitting pins and thimbles.”

On November 22, 1827, the shop of William & Fairchild in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, ordered “brushes, spoons, thimbles, violin strings, steel traps, curry combs, sad irons, trace chains, etc.” from the firm.

As his business grew, Seabury and his partners continued the tradition of hiring clerks to do the daily work of the company while learning the trade. William Floyd-Jones, from Oyster Bay, Long Island, started out in 1831 as a clerk for “the highly respected wholesale hardware house of Tredwell, Kissam and Co.” and became a member of the firm in 1837, retiring in 1855.

Trade Tokens

Trade tokens were often used by businesses either to provide sufficient currency during times of coin shortages (especially when stores were in remote locations away from banks), to extend credit, or as a form of advertising, to let potential customers know their location and the services and goods available. In 1823, and again in 1825-26, Tredwell, Kissam and Company issued trade tokens, struck by Kettle & Sons of England, to commemorate the opening of the Erie Canal, referred to on the coin as the “Grand Canal.” According to Robert D. Leonard, a collector of trade tokens, most of the pieces made for commemoration saw limited circulation as money.

.

.

.

The South Beckons

Seabury did not limit his business to the New England or Mid-Atlantic states. Like many other merchants who realized the huge market for goods in the South, he did business with and extended credit to storekeepers in Alabama and the Carolinas. As early as 1816, Tredwell & Kissam was advertising in Southern newspapers. In an advertisement placed in The American (Fayetteville, North Carolina) on October 17, 1816, they advertised hardware and cutlery “to suit the country trade.”

Typically, a traveling salesman, or “drummer,” would venture to faraway cities to provide catalogs, collect orders, and in many cases, settle overdue accounts. In a letter to Tredwell, Kissam & Company dated January 11, 1831, from a Montgomery, Alabama, storeowner named William Shute, he references a “Mr. Smith,” who was apparently a drummer for Tredwell, Kissam, and Company: “…your Mr. Smith left here a few days ago. He said you have a fine stock of guns and Memo to order. Below we hand you an order for such goods as we are in immediate want of which you will please ship by 1st vessel for Mobile.” Shute goes on to list the desired goods, including guns, corn mills, and padlocks.

Tredwell, Kissam and Company must have had strong commercial ties to North Carolina, for in 1831 they donated $100 towards the relief of citizens of the city of Fayetteville, after a disastrous fire that took place there on May 29.

.

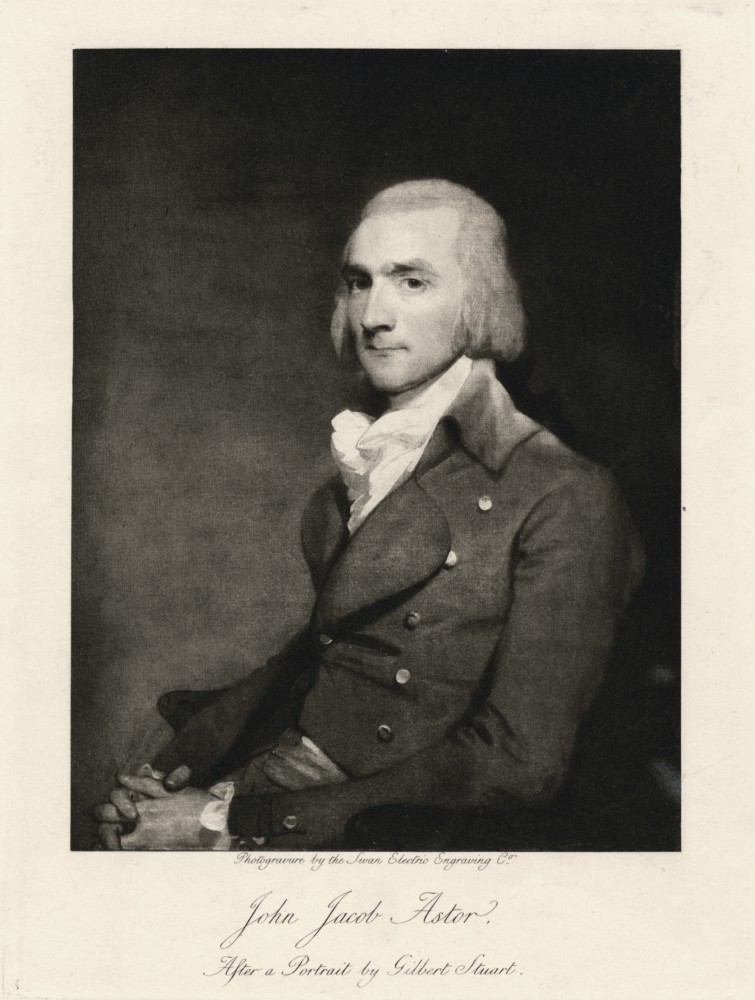

A Famous Client

Undoubtedly the most famous client of Tredwell, Kissam, and Company was John Jacob Astor (1763-1848), the German-born fur trader and real estate investor who at his death was the wealthiest man in America, with a fortune worth approximately $20 million. Records of Astor’s American Fur Company indicate that he purchased guns from Tredwell, Kissam, and Company in 1832 and 1833, for use in trade with Native Americans in exchange for furs. In a “Memorandum of Guns to be Furnished,” dated October 31, 1832, Astor gives very specific instructions as to the quality of the guns, indicating that a previous shipment had been of less than desirable quality:

“The stocks of many of the guns you gave us last spring were made of two pieces of wood united at the gap … This must not on any account be the case with the present order…Our Indians consider them not new, but old arms patched up, and in numbers instances have returned them to our traders, [illegible] them with having practiced an imposition, by selling them a mended article for one that was new and perfect in every respect. The pernicious effect of such an impression is of too much importance to our interest to be overlooked.”

The Memorandum stipulates that the specific order of 410 guns must be “ready for delivery” by April 10, 1833, which gave Tredwell, Kissam and Company six months to import the guns from England, then pack and deliver them. This order indicates the long turnaround time from ordering to acquisition and delivery of goods.

Guns and Cotton Trade

The above-mentioned orders from Shute and Astor point to a shift from hardware to guns on the part of Tredwell, Kissam, and Company. Although America was beginning to manufacture guns in small amounts (Derringer in 1810, Remington in 1816, and Colt in 1836), by 1815 the British were mass-producing millions of guns per year; Seabury’s company relied on overseas production to readily fill their large orders. The English fowling gun, used to hunt birds and fowl, was made in Birmingham, England, and was primarily sold to Native Americans.

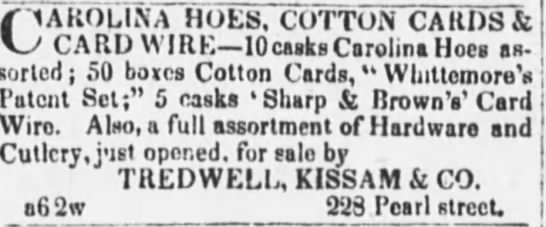

Although Seabury’s company did not engage in the rapidly growing cotton industry on a large scale (by the mid-1840s, cotton accounted for almost 45 percent of the gross national product), they did sell items that supported the trade, and, in at least one instance, sold cotton. In an advertisement in the Evening Post (December 23, 1819), the company offered “7 bales Cotton (new crop), landing from sloop Cashier.” This appears to be a one-time venture, however. What Seabury did sell in considerable quantities were cotton cards, tools used to process raw cotton in small amounts for lower-scale production. The cards disentangled and cleaned the raw cotton fibers after the cotton was picked. He also occasionally sold hemp cotton bagging, which was used to pack bales of cotton.

A Rich Man

In 1822, Lanier’s A Century of Banking in New York, 1822-1922 (1922), included Seabury in a list of “The Rich Men of 1822,” wherein the value of his personal property, from 1815 to that date, was listed as $17,500. This was quite a significant amount of money for that time, especially considering that it references only Seabury’s personal property. Seabury was living in the boardinghouse during those years, so this amount represents the value of his business and whatever chattel he owned. The real property he owned at that time (Seabury’s real estate ventures will be discussed in the next post) was not included in this estimate.

A Prince among Princes

On January 11, 1834, one year before his retirement, Seabury was a pallbearer at the funeral Thomas Seaman Townsend (1771-1834), held at St. George’s Episcopal Church (then located on Chapel Street, now Beekman), where Townsend was a vestryman. Townsend was a wealthy merchant who was a neighbor of Seabury’s on Dey Street. The names of pallbearers who joined Seabury that day reads like a list of merchant elite of New York, including such highly regarded men as Benjamin Strong, Anthony Underhill, and Stephen Van Wyck.

The End of an Era

On February 4, 1835 the following notice appeared in a New York newspaper, indicating the end of a 20 year partnership:

“The firm of Tredwell, Kissam & Co. is dissolved by mutual consent. Seabury Tredwell and Samuel Kissam retire. Either of the Partners will attend to the settlement of the business, at 228 Pearl-street.” [Signed] Seabury Tredwell, Joseph Kissam, Samuel Kissam New-York, January 31, 1835.”

The same day, Joseph Kissam announced that he had formed a new partnership with James A. Smith and William Bryce, and would continue the hardware business under the name Kissam & Co.

Although Seabury was only 55 years old when he retired, he had been in the hardware business for many years, roughly from 1800 to 1835. That is a long career by any standard. After such an extended, successful run, it is no wonder Seabury decided to retire. And no doubt he trusted that his nephew Joseph would continue the business he had worked so hard to establish.

A New Life Uptown

On October 31, 1835, Seabury sold his home on Dey Street to his former partner Joseph Kissam for $10,000. Two days later, he purchased a new home at 361 Fourth Street, for the hefty sum of $18,000. The seller was Joseph Brewster, a hatter and real estate speculator, who had built the late-Federal and Greek Revival row house three years earlier. Seabury, with his wife, Eliza, and seven children, bid farewell to the hustle and bustle of lower Manhattan, and moved to the elite Bond Street neighborhood. Thus began Seabury’s retirement, and another chapter in the life of this wealthy New York merchant.

Sources:

- Account of William & Fairchild. William B. Pennebacker Watermark Collection, 1710- ca. 1936. The Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera. Winterthur Museum. findingaid.winterthur.org: Box 3, Folder 15.

- Alabama State Archives. Record Book of William Shute, of Shute and Hackett, 1834-1837.

- Albion, Robert Greenhalgh. The Rise of New York Port [1815-1860]. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1939.

- The American. October 17, 1816, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/16/19.

- Atherton, Lewis E. “The Problem of Credit Rating in the Ante-bellum South.” The Journal of Southern History. Vol. 12, No. 4 (Nov., 1946), pp. 534-556). www.jstor.org. Accessed 3/17/19.

- Atherton, Lewis E. “Predecessors of the Commercial Drummer in the Old South.” Bulletin of the Business Historical Society. Vol. 21., No. 1 (Feb., 1947), pp. 17-24. www.jstor.org. Accessed 3/18/19.

- Barrett, Walter [pseud.] [Scoville, Joseph A.]. The Old Merchants of New York City. New York: [various publishers]: 1863-1866. www.archive.org. Accessed 4/28/19.

- Black, Samuel W. “Tools of Oppression: Cotton Cards.” Collection Spotlight at the Heinz History Center Blog. www.heinzhistorycenter.org. Accessed 3/17/19.

- Burrows, Edwin G. And Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Calendar of the American Fur Company Papers. Orders Outward, Volume 2, 1827-1833. Manuscript Collections, New-York Historical Society.

- Commercial Directory, Containing a Topographical Description…” Philadelphia: J.C. Kayser & Co., 1823.

- Davenport, Linda Haas. Haas/Davenport Homepage. www.lhaasdav.com. Accessed 3/18/19.

- Elihu Harrison Papers, 1812-1836. Litchfield Historical Society.

- Elijah Boardman Papers, 1782-1853, Litchfield Historical Society.

- Evening Post. September 11, 1812, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 5/6/19.

- Evening Post. November 2, 1815, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/23/15.

- Evening Post. August 16, 1816, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/23/15.

- Evening Post. December 23, 1819, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/28/19.

- Evening Post. March 3, 1824, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/23/15.

- Evening Post. April 4, 1832, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/23/15.

- Fayetteville Weekly Observer. November 16, 1831, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed May 25, 2017.

- [Green, Asa}. The Perils of Pearl Street, Including a Taste of the Dangers of Wall Street. New York: Betts & Anstice, 1834.

- “John C. Tucker.” The Iron Age: A Review of the Hardware, Iron, and Metal Trades. Volume 49, February 18, 1892, pp. 321-22. New York: David Williams. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 4/23/19.

- Lanier, Henry W. A Century of Banking In New York, 1822-1922. New York: G.H. Doran Co., 1922.

- Leonard Jr., Robert D. “Collecting U.S. Tokens: Challenges and Rewards.” Chicago Coin Clu, 1986. wwwchicagocoinclub.org. Accessed 4/26/19.

- Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1784-1831.New York: The City of New York, 1917. www.archive.org. Accessed 3/1/19.

- Newtown Register, Thursday, February 13, 1896: www.fultonhistory.com. Accessed 3/12/19.

- New York Land Records, Conveyances, 1835-36 vol. 343-345. www.familysearch.org.

- Public Documents Printed by Order of the Senate of the United States, Volume II. United States Congressional Serial Set, Volume 239. Washington, D.C.: December 1, 1834. www.books.google.com. Accessed 3/18/19.

- Sells, Steve. Traditional Muzzleloader. www.traditionalmuzzleloader.com. Accessed 5/4/19.

- Shipping and Commercial List and New-York Price Current. February 4, 1835, p. 3. America’s Historical Newspapers. www.newsbank.com. NYPL. Accessed 6/29/17.

- Townsend, Margaret. Townsend-Townshend, 1066-1909. New York: [Press of the Broadway Publishing Company], p. 107. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 4/23/19.

Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part 1 – The Early Years

by Ann Haddad

A Revolutionary Birth