Sylvia’s Life Unveiled

Once I knew Sylvia’s name, I researched archives in both New England and New York to learn more about her life. I could find only the dates of her birth, marriage, and death, written in musty old ledgers. Then one day, a fortuitous Internet search led me to Sylvia’s great-granddaughter, who had a steamer trunk filled with Sylvia’s possessions, including letters and journals, dresses (that eerily fit me), and photographs of Sylvia as a young woman. Sylvia’s life soon unfolded before my eyes. Though we were born 133 years apart, I have come to know Sylvia better than most people in my life today.

Through the years, Sylvia’s great-granddaughter, now in her eighties, has been extraordinarily kind and supportive of my quest to bring Sylvia to life. If it were not for her generosity, I would have had to write Sylvia off to historical fiction. I am forever beholden to her.

Displayed here are traces of Sylvia’s life that I uncovered after meeting her great-granddaughter.

A Daughter of the American Revolution

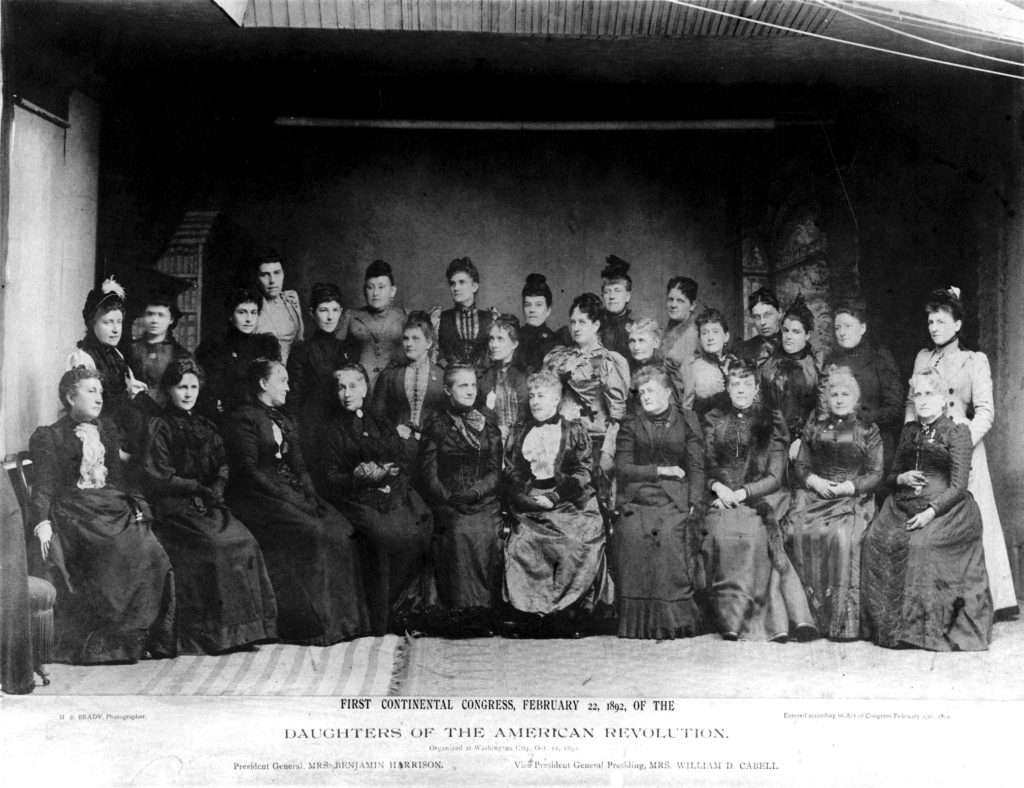

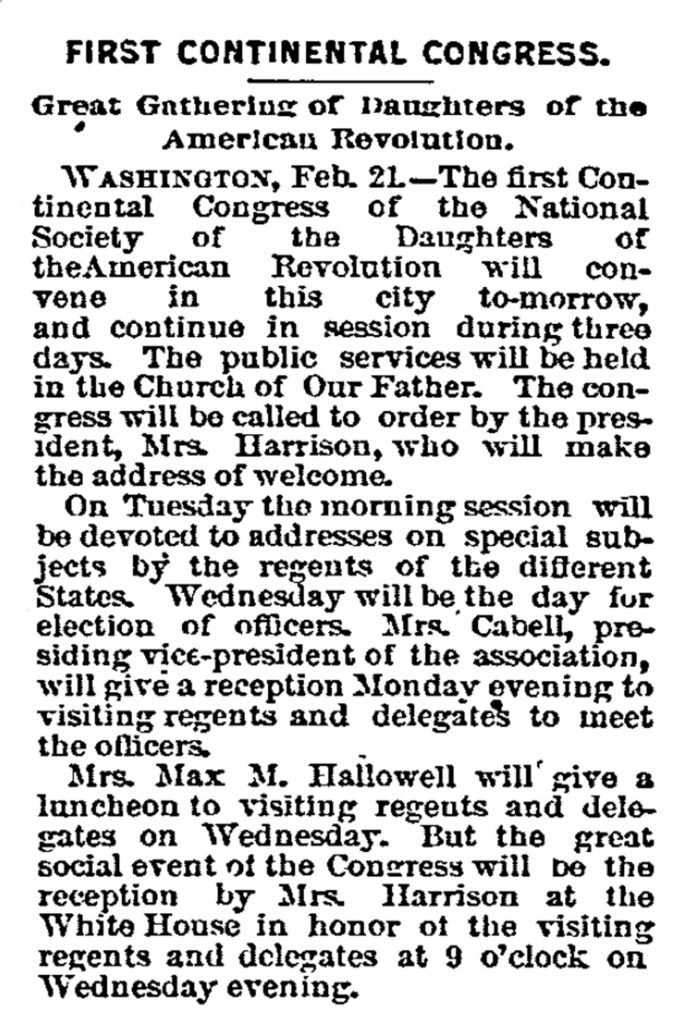

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) was founded in 1890, after the Sons of the American Revolution, formed in 1889, voted to exclude women as members. Sylvia, as the great-granddaughter of John DeWolf, a private in the Revolutionary War, was accepted on December 14, 1891; she was the organization’s 933rd member.

Two months later, on February 22, 1892, Sylvia attended the DAR’s first Continental Congress in Washington, DC. Caroline Harrison, the First Lady, held a reception for the DAR Regents at the White House.

Was Jud the Love of Sylvia’s Life?

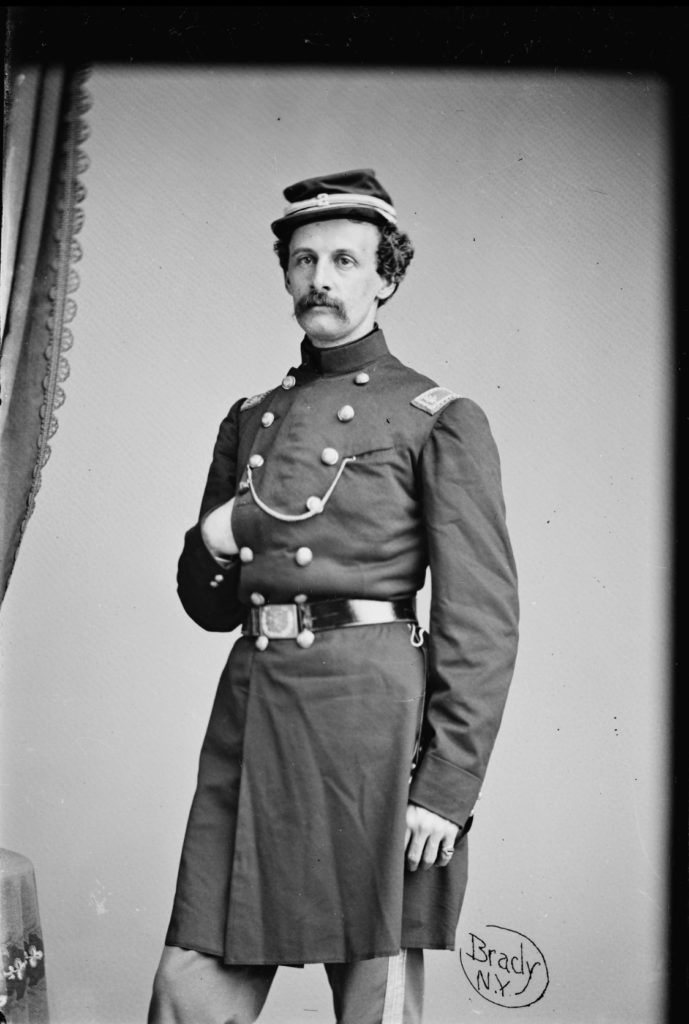

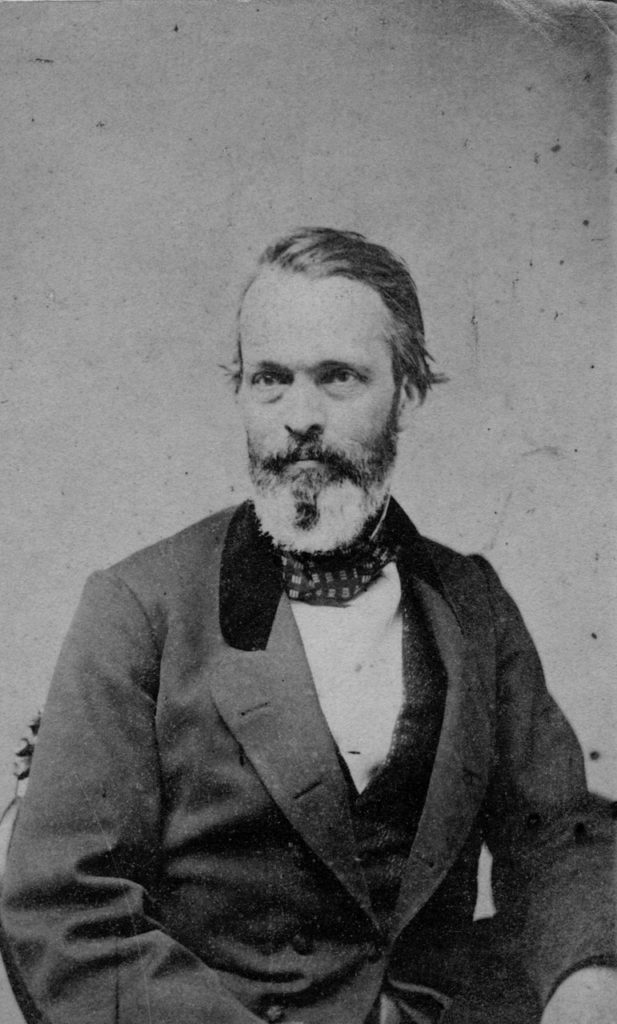

Joseph Judson Dimock (Jud) was married to Sylvia’s cousin, Isadora DeWolf. During the Civil War, he served as a major in the 82nd New York Infantry and, in the summer of 1861, Jud wrote letters to Sylvia. Sylvia was 20 and engaged to Jud’s brother William; Jud was 34. Ambiguous references, in both Jud’s letters and Sylvia’s journals, point to a possible romantic connection.

On August 4, 1861, he writes: “I want to see you very much and have a good long talk about ourselves, and matters that have occurred since we met. I have often thought of you and wished to see you but the Fates seem to interfere, so we must wait patiently until the appointed time as the scriptures saith.”

And just three weeks later, he writes: “You know my fondest wish is to see you happy, and to have you to love and cherish as a sister would be next to love you as my own wife.”

In this same letter, Jud writes that he does not question Sylvia’s love for William, but he is pointed in his doubts about William’s sustaining a lasting affection for her. Jud warns her of his brother’s “follies” with other women.

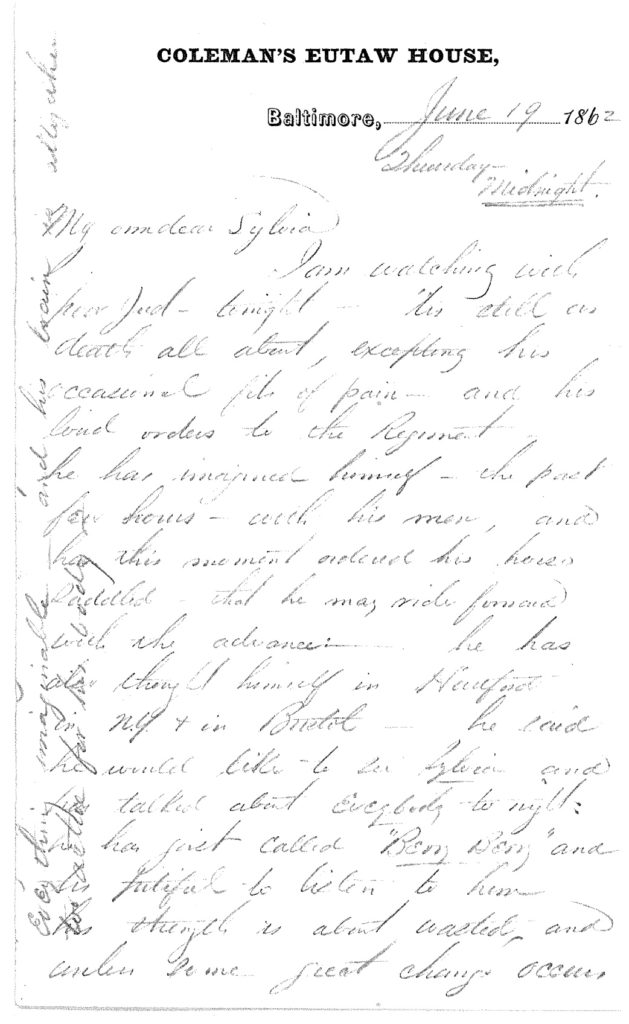

Jud died in June 1862 of typhoid fever. As Sylvia’s journal entries attest, his loss was devastating. She expresses her deep sadness, describes her journey to Hartford, Connecticut, in the pouring rain for the funeral, and wonders, “What will we all do without him?” After the funeral, she takes flowers from his grave as a remembrance.

In October, four months after Jud’s death, Sylvia married William. Shortly after the marriage, she began writing in her journal about her husband’s alcoholism, physical abuse, and desertion. In April 1864, she writes: “Feeling miserably all day long. Went to ride with William. The doctor came and vaccinated and He came home drunk, beats me and hurt the baby.”

Sylvia expresses much sadness and anger in her journals through the years, but she also shows resilience. She is often apart from William and seeks the council of others to help her with financial matters. Though divorce was legal, it was not considered proper for a woman of her social standing.

I will always wonder if Sylvia married William because she could not marry Jud and believed it to be the next best thing, sadly to be proven disastrously wrong.

Sylvia’s Family

Sylvia was the first child of Jonathan Russell Bullock and Susan Amelia DeWolf. Sylvia’s father (1815-1899) was a lawyer; in 1860 he was elected Lieutenant Governor of Rhode Island. Sylvia’s mother (1820-1866) was a member of the wealthy DeWolf family of Rhode Island, who made their fortune in the Triangle Trade.

Sylvia’s maternal grandfather, John “Fessor” DeWolf (1786-1862), was a highly distinguished scholar of English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, ethics, mathematics, chemistry, and astronomy. He was a professor of chemistry at Brown University from 1817-1837, and was also a poet. He died in 1862, when Sylvia was 20; she writes in her journal, “I came home, found a telegram that Grandpa DeWolf was dead, so I had to give up going to the Sociable. So disappointed.”

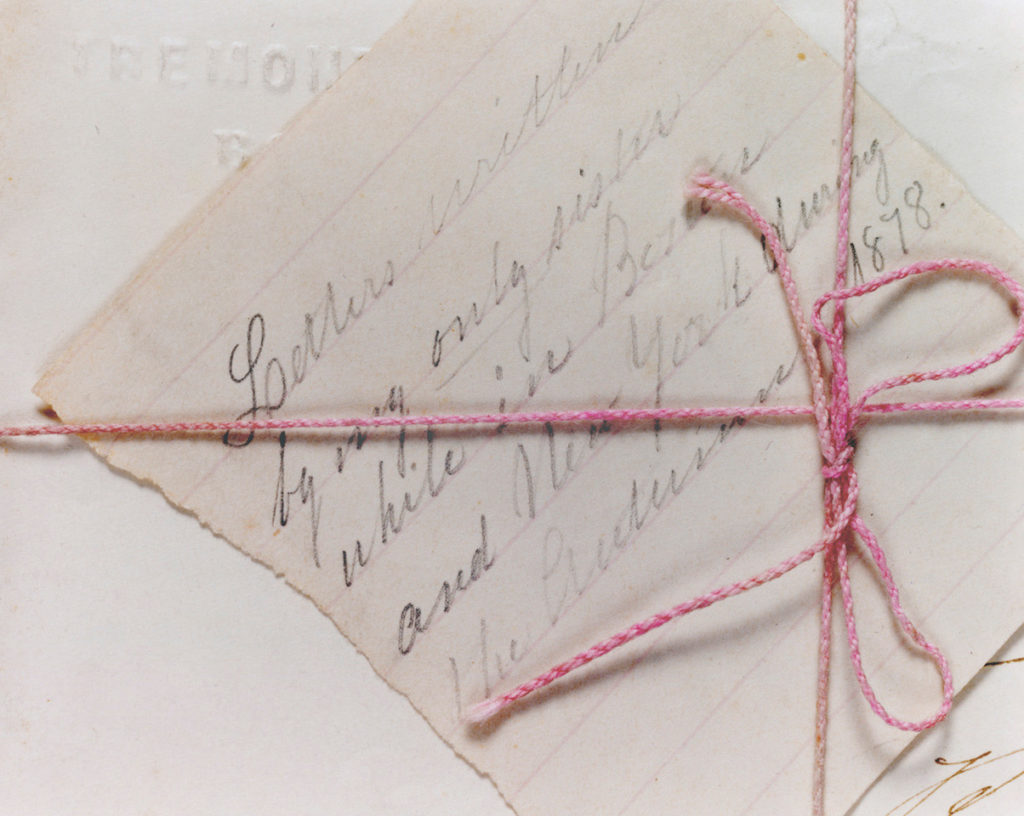

Sylvia was especially close to her sister Annie, who was just two years younger. She did not have much of a relationship with her other sisters; Sylvia was 17 years old when her sister Elizabeth was born, and nearly 30 when her half-sister, Emma, was born. Annie never married, and died in New York City in 1883.

The Triangle Trade

In the 18th and early 19th century, Sylvia’s great-grandfather John DeWolf and his brothers were involved in the Triangle Trade. Sylvia’s great-granduncle James DeWolf was said to be the second-richest man in the United States by the end of his life. The DeWolfs made rum in their distilleries in Bristol, Rhode Island, then sailed to West Africa where they traded the rum for men, women, and children and brought the captives to family-owned plantations in Cuba. The enslaved were later taken to Charleston, South Carolina, or auctioned in Havana, and the DeWolf ships in Cuba were filled with sugar to bring back to Rhode Island to make more rum.

In 2008, Katrina Browne, a DeWolf descendant, produced and directed an Emmy-nominated PBS documentary film entitled Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North. The film follows ten DeWolf descendants as they retrace the Triangle Trade and their family’s past. In 2009, she and others founded the Tracing Center “to create greater awareness of the full extent of the nation’s complicity in slavery and the transatlantic slave trade and to inspire acknowledgement, dialogue and active response to this history and its many legacies … for the purpose of racial justice, healing, and reconciliation, for the benefit of all.” One family member in this film, Tom DeWolf, has written multiple books on the legacy of the slave trade, which have opened dialogue on how to build racial healing in the present.

Sylvia was born after her great-grandfather had died. I do not know how much Sylvia knew about her ancestors’ involvement in the slave trade, or what views she might have held.

Sylvia: A 19th Century Life Unveiled |

||||

.

..Overview... |

..Sylvia’s Story: The Beginning.. |

..Sylvia’s Life Unveiled.. |

..No-When.. |

..Sylvia as Muse.. |