Miracle on Fourth Street:

The Early Years

Gertrude Tredwell, the youngest of Seabury and Eliza Tredwell’s children and the only one born in this house, died at 29 East 4th Street in 1933, leaving the house complete with the family’s original furnishings, decorative arts, and personal possessions, even clothing. Gertrude had outlived the family fortune and, after her death, the house and its contents were to be sold at auction. George Chapman, an attorney and a relative of the Tredwells, realized the tremendous historic value of the house and made the necessary legal and financial arrangements to turn it into a museum. The museum, then known as the Old Merchant’s House, opened to the public in 1936. George Chapman would devote his life – and fortune – to preserving the Museum until his death in 1959.

The House Is Saved “At the Eleventh Hour”

|

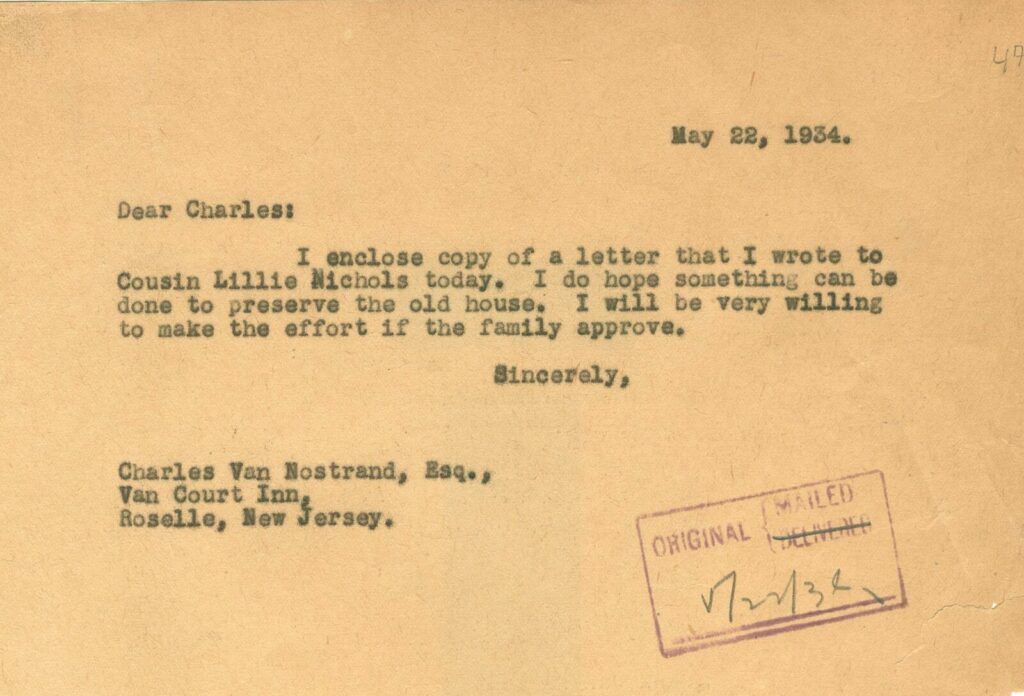

“I do hope something can be done to preserve the old house. I will be very willing to make the effort if the family approve.” — Letter from George Chapman to |

According to George Chapman, “At the eleventh hour, Charley Van Nostrand, appealed to me to rescue the place. The sale was scheduled for the very next day … I long-distanced Lillie [Gertrude Tredwell’s niece and heir] at her summer home in Connecticut, made her an offer for the house and contents. She accepted it and promised to telephone the auctioneer.”

Renovation Work Begins

In addition to the work necessary to modernize the house to into a museum (adding visitor restrooms, electricity, and central heating), George Chapman consulted William Sumner Appleton, founder of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, for advice on preserving the house. In 1935, Chapman wrote, “The plan is to put the house in good order, fix up the furniture, etc., eliminate later additions and keep it in its original period, charging an entrance fee to visitors. […] As far as we know, it is the only actual city house of any pretensions and of that period still extant, or at least is the only one in any state of condition, and with the furniture, etc., intact.”

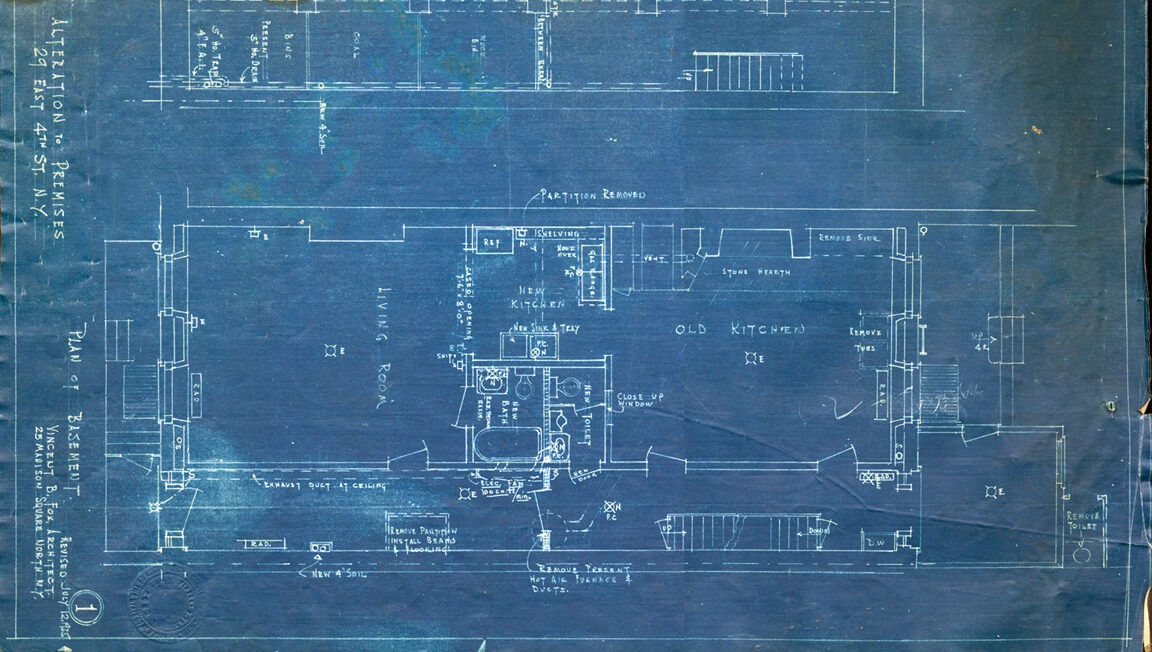

In 1935, as he began renovation work to turn the house into a museum open to the public, George Chapman hired architect Vincent Fox to draw up plans of the building.

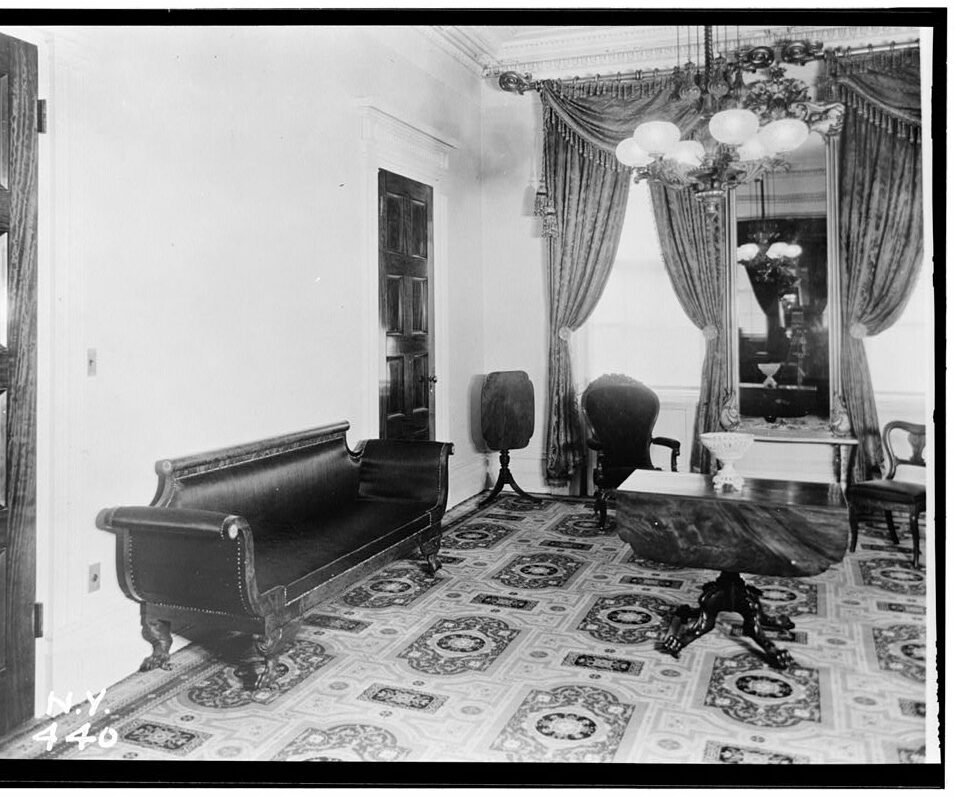

In 1936, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) documented the Merchant’s House with interior and exterior photographs and architectural drawings. HABS, a program run by the National Parks Service, was established in 1933 to provide work to architects, draftsmen, and photographers who lost jobs during the Great Depression. According to the program’s founder, Charles Peterson, “Our architectural heritage of buildings from the last four centuries diminishes daily at an alarming rate. The … demolition and alterations caused by real estate ‘improvements’ form an inexorable tide of destruction destined to wipe out the great majority of the buildings which knew the beginning and first flourish of the nation.”

The Museum Opens

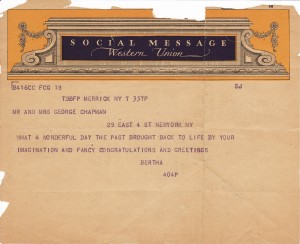

The Old Merchant’s House opened to the public as a museum on May 11, 1936. It was open seven days a week: Sundays from 1 to 5 p.m., and Monday-Saturday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Admission was 50 cents; schoolchildren were admitted free of charge.

Elizabeth Tredwell Stebbins, one of Seabury and Eliza Tredwells’ granddaughters, wrote to George Chapman to thank him for restoring her father’s childhood home:

“Dear Cousin, It would be impossible for me to find words adequate to express my appreciation and admiration for the wonderful work you and your wife have done at 29 East 4th Street. Father loved the old place very much and I was brought up to appreciate its natural beauty. I know how pleased he and my dear sister Lizzie would be with it.”

The Struggle to Raise Funds

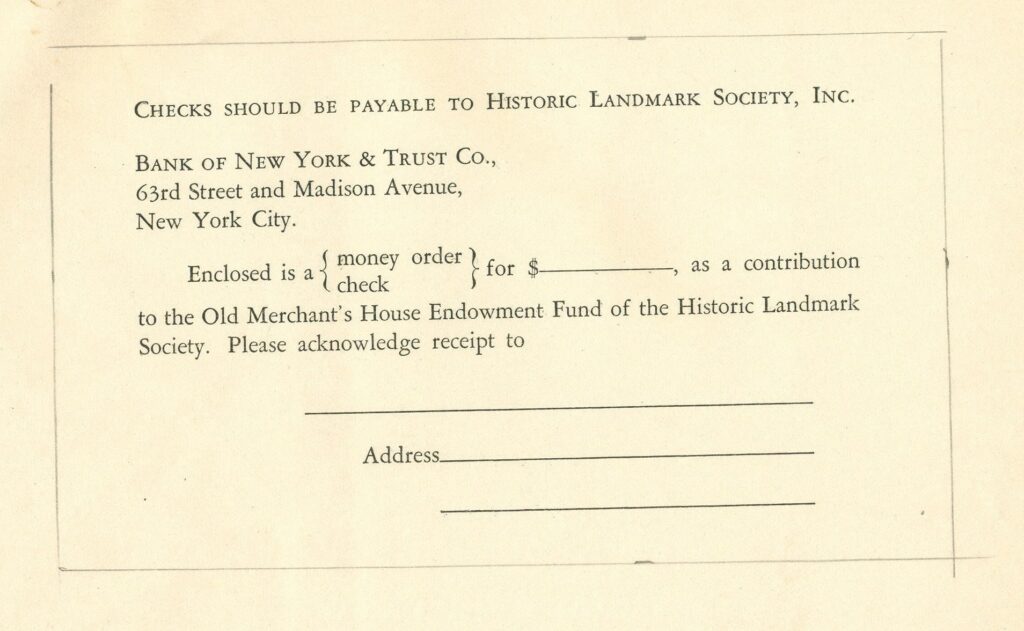

Soon after the museum opened, Chapman’s health began to decline. He realized that if the house were to survive him, it would need to be self-sustaining. In 1938, he began a fund-raising campaign, hoping to raise a $100,000 endowment. Although Chapman admitted that the timing was not ideal for a fundraising appeal, he was encouraged when the very first donation was an astonishing $50. Ultimately, the campaign would prove a disappointment, raising a meager $220. Over the next two decades, Chapman would spend over $50,000 of his own money to preserve the house.

Miracle on Fourth Street: 85 Years as a Museum |

||||

.

..Overview... |

..The Early Years.. |

..Mid-Century Changes.. |

..An Architect Steps In.. |

..The ’90s to Today.. |