Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part 1 – The Early Years

by Ann Haddad

A Revolutionary Birth

When Seabury Tredwell was born in the village of Hempstead, Long Island, on September 25, 1780, his family and other members of his farming community were in the midst of the suffering and havoc caused by the ordeal of seven long years of British occupation during the American Revolution. The countryside had become one large British military camp, and residents (both Patriot and Loyalist) saw their property confiscated, their rights disregarded, and their families divided. No doubt an air of disillusionment and disorder pervaded the village; this continued for a time after the war ended in 1783 and the unimaginable had occurred: the Patriots had defeated the fearsome British Army. As Hempstead began to rebuild and restore its land and shattered village, as the new order of government was formed, and as the animosity that had severed family ties abated, Seabury Tredwell, a future “merchant prince” of New York City, was growing up.

A Classical Education

Seabury’s parents, Dr. Benjamin Tredwell and Elizabeth Seabury Tredwell, most likely decided to send their son to the school in Hempstead begun by Elizabeth’s father, Reverend Samuel Seabury (1706-1764). Reverend Seabury became rector of St. George’s Church in Hempstead in 1743; to compensate for the inadequate salary the position provided, he opened the school sometime around 1762. According to an advertisement on March 27, 1762, in the New York Mercury, the annual tuition of 30 pounds sterling included room and board, as well as “washing and wood for school-fire.” Housed in the rear of the parsonage, the school acquired an excellent reputation over the years, while providing a classical education to the children of notable New York families and Tredwell relatives, including the Onderdonks and the Kissams. During Seabury’s school years, the rector of St. George’s (and likely Seabury’s teacher) was Reverend Thomas Lambert Moore (1758-1799).

Move to the Big City

It is uncertain when Seabury moved to New York City to begin his adult life and start a business. Most likely, he arrived in New York City sometime between 1798 and 1801, when he was between 18 and 21 years old, and had “come of age.” An obituary (source unknown), published at his death in 1865, notes that, “He came to this city in 1798 [he would have been 18 years old] and after serving as a clerk for three years started the hardware business on his own account.”

Two of Seabury’s older brothers had preceded him and were established as merchants by the time he arrived on the scene. Adam Tredwell (1772-1852), who became a hugely successful fur merchant, first appeared in the Directory 1795 as a partner in Tredwell & Thorne, on 21 Burling Slip, when he was 23 years old. John Tredwell (1775-1851) appeared in 1796 as a china and glassware merchant on 197 Water Street. He was 21 years old. Both men may have arrived earlier and clerked for others before becoming merchants in their own right.

Merchants and their families often shared living quarters with their employees “above the store.” As a clerk, Seabury may have lived in the shop of his employer; it is unclear if he would have been listed in the Directory as such. His two older brothers married in 1801, and it is doubtful that Seabury lived with them for any length of time. He is not listed in the 1800 Federal Census (the Census only listed the head-of-household and number of residents at each address); his name does not appear in the Directory until 1803, where he is listed as a merchant at 260 Pearl Street. He was 23 years old at that time.

Yellow Fever Strikes

Seabury’s arrival in New York City may have been delayed by the appearance of the worst yellow fever epidemic in New York City history, in August 1798. It continued through late October, claiming 2,086 victims. Residents fled the city in hope of escaping the scourge. Seabury did not turn 18 until September 25 of that year; he surely waited for the epidemic to subside before moving to the city. The death of his first cousin, James Tredwell, on October 8, 1798, likely caused great consternation among Seabury’s family, discouraging him from leaving Hempstead. James was a physician who died at the age of 30 while treating yellow fever victims.

Seabury Tredwell, Volunteer Fireman

In 1805, two years after his first listing in the Directory, Seabury’s name again appeared in the public record. In the Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, May 20, 1805, it is noted:

“Gurdon Manwaring, Seabury Tredwell and John L. Embree were appointed firemen of Company No. 18, instead of Alsop Hunt, Sands Ferris and Edmund Fanning resigned.”

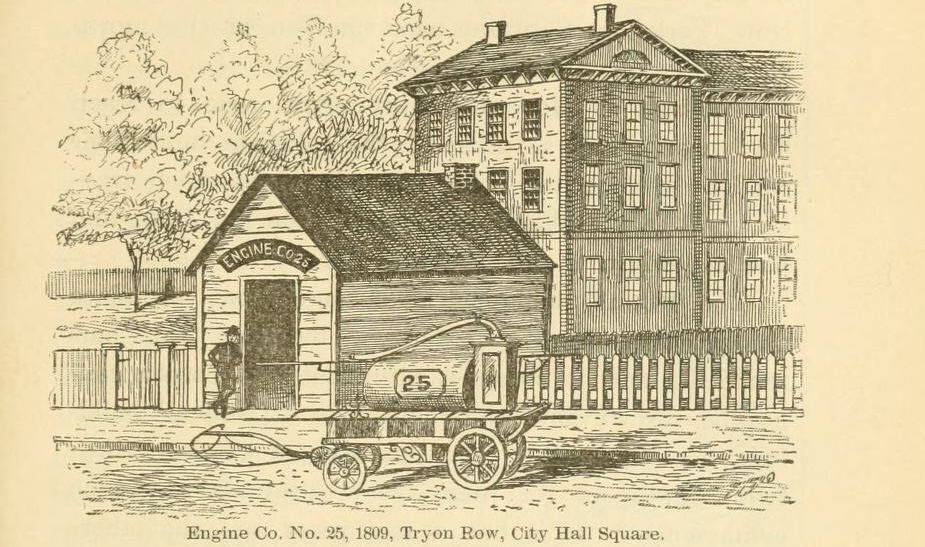

Seabury became a fireman during the volunteer era of firefighting; firefighting in New York City did not become a salaried position until 1865. New York City had established the voluntary New York Fire Department in 1786. The method of fighting fires involved mobilizing the volunteer company (each with 18 “able-bodied, sober men”), to participate in a bucket brigade, in which buckets of water were taken from a well and passed hand to hand to fill the cisterns of the hand fire engine pumps. In 1791, the Common Council passed an ordinance stipulating that each city ward have a designated Fire Warden. The Warden’s role was to examine the houses and buildings in his ward to ascertain that each possessed the required number of leather buckets (one per fireplace). The buckets, with a capacity of at least 2.5 gallons of water, were to be marked with the initials of the landlord (who purchased them at his own expense), and were to be hung by the front door.

| … |

The ordinance also required firemen to:

“at least once a month to exercise with their engines, etc., and to wash, clean, and examine them, under a penalty of six shillings; and for every failure to attend at a fire, and for leaving his engine while at a fire, and for failure to do his duty at a fire, a fine of 12 shillings is imposed, and to be removed from office as a fireman.”

According to Our Firemen: The History of the New York Fire Departments… (1887), Seabury’s Company, Engine Company 18, or the “Union,” was organized in April 1792, and was originally located on John Street, near Pearl Street. In 1813, its location was moved to 228 Water Street, and later to Fulton Street. The company was disbanded in 1828.

By 1805, the year Seabury was appointed Fireman, there were approximately 700 firemen in the ranks. We have no further record of Seabury’s involvement with the New York City Fire Department.

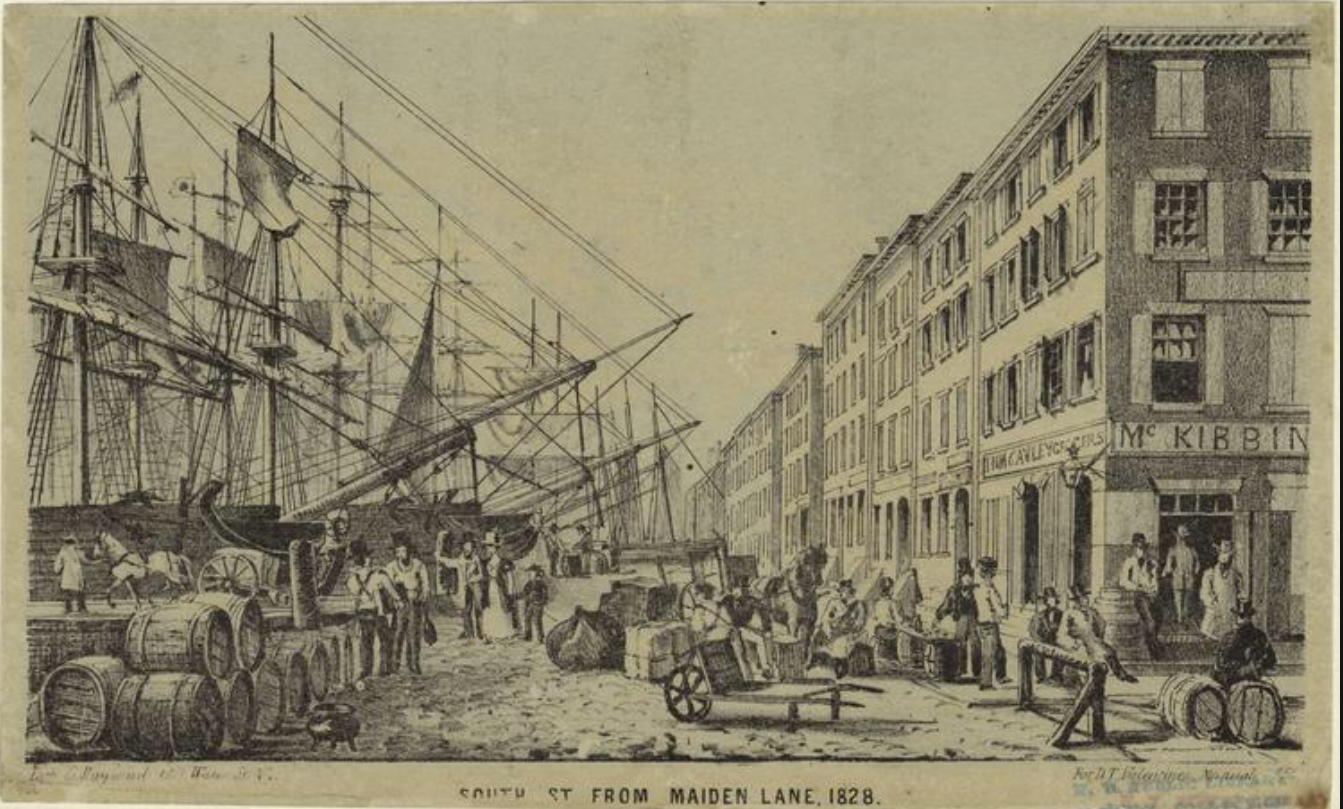

The Seaport Air Turns Sour

As a result of rapid urban growth and increasing commercial and mercantile development by the early 19th century, the lower Manhattan waterfront became an overcrowded, disease-prone, shanty-filled neighborhood that drew residents from all walks of life. The usual custom of living and working in a common space therefore became untenable to affluent gentlemen with families. Living “above the store” was no longer genteel. Adverse to socializing with the lower classes, these men of means sought to separate their homes from their businesses, and sought dwellings in cleaner and safer, i.e., more upscale, residential neighborhoods. Lower Broadway, and the neighborhood to its west, including streets that ran to the North (now Hudson) River, such as White, Barclay, Dey, Warren, and Vesey, became a popular haven for the wealthy. According to Burrows and Wallace in Gotham (1999),by 1810 more than half the merchants or professionals in the Directory listed separate work and living addresses. And, once they left the seaport area, the elite no longer wanted to provide living quarters for their workers.

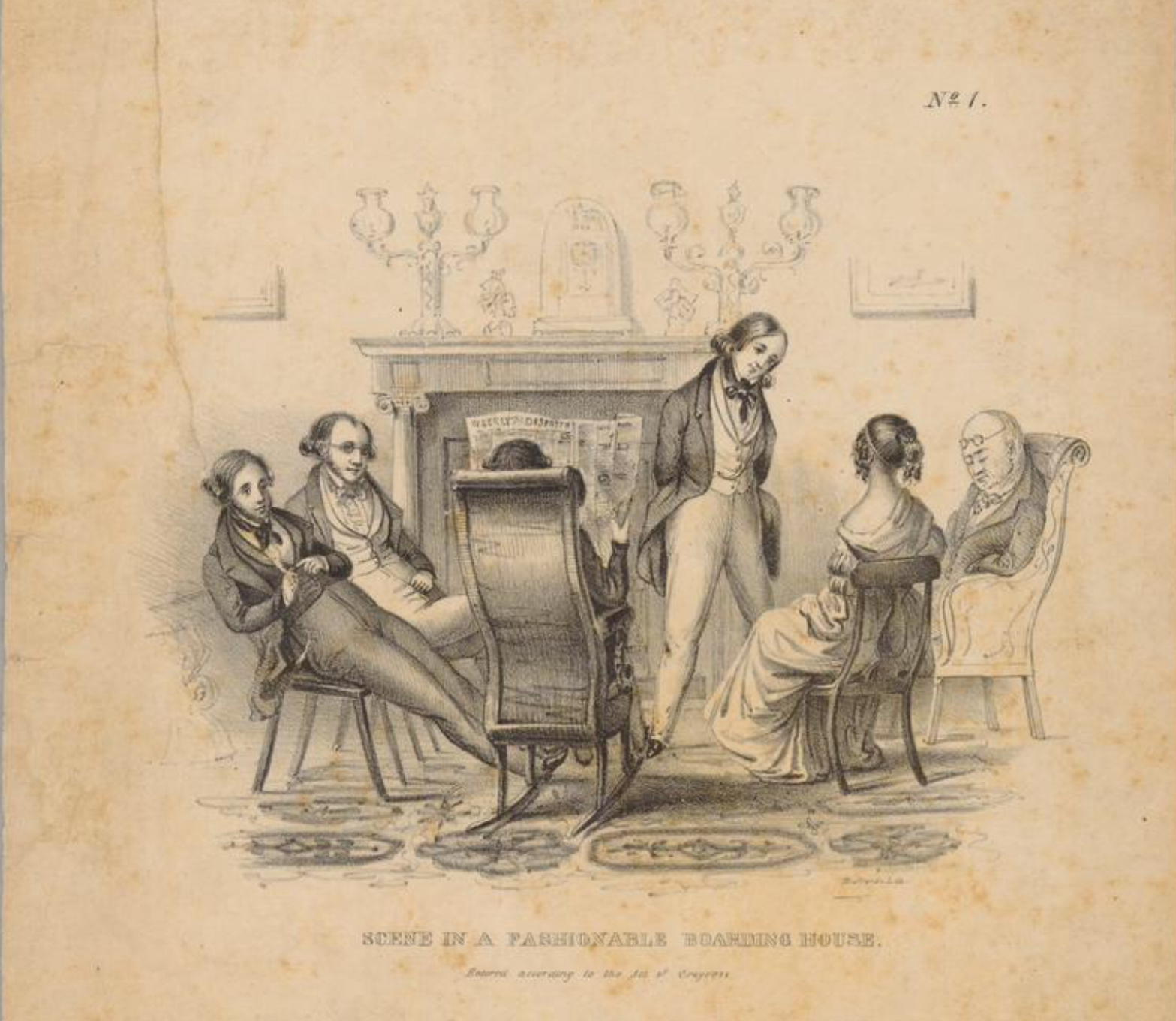

A City of Boarding Houses

This presented a dilemma for single young men newly arrived in the city. They could neither afford to live in nor did they need an entire house for themselves in more expensive neighborhoods. As a result, the humble boarding house became the solution to their housing needs. These were public establishments (often converted from the former homes of the wealthy who had moved on to more appealing surroundings) that provided room and board for a price; they became a popular living option for men like Seabury Tredwell. Wendy Gamber, in The Boarding House in Nineteenth-Century America (2007), estimates that “between a third and a half of nineteenth century city dwellers either took in boarders or were boarders themselves,” and of the latter, the majority were single young men.

Many boarding houses were located in the center of town, that is, the congested, dirty, mercantile area, near the bustling wharves of the East River. Here the warehouses that could provide employment were nearby, and housing was affordable. Living in a boarding house often brought together men of similar interests; newcomers sat side by side at the dinner table with more experienced residents, who could educate them in the social and work habits of city people, and provide companionship.

We don’t know what Seabury’s rent was during his boarding house years. Gamber states that in the mid-nineteenth century the standard weekly rate for lodging and meals was between $3 and $4, equivalent to approximately $125 today. Seabury, who boarded from approximately 1800 to 1820, most likely paid less.

Widow Williams

The two boarding house owners who figured prominently in Seabury’s story were widows. Widow Susannah Williams, who ran the boarding house where Seabury eventually lived, first appeared in the New York City Directory in 1799, when her establishment was on 31 Lumber Street (now Trinity Place). She subsequently moved to Harmon Street (now East Broadway), then to 263 Pearl Street, in 1805. Seabury’s first location of his hardware business (from 1803 to 1809), was 260 Pearl Street; Mrs. Williams’ boarding house was across the street. Their proximity may be what led them to meet. In 1810, Mrs. Williams relocated to 282 Pearl Street, and two years later, in 1812, Seabury Tredwell was listed at this address in the Directory.

It is noteworthy that in the 1812 Directory, the occupants of Mrs. William’s boarding house are actually listed. Seabury’s name appears, as does his younger brother George Tredwell (1784-1848), who first appears in the Directory in 1805, at the age of 22, at Seabury’s business address of 260 Pearl Street. Perhaps George apprenticed under Seabury; he would eventually join his brother John in the china business.

Due to space and financial constraints, boarders frequently shared rooms with one another. Seabury and his brother George, two of four boarders at Mrs. Williams’ in 1812, probably shared a room (and a bed) when they lived there.

Widow Parker

In 1814, approximately one year after the death of her husband, Seabury’s future mother-in-law, widow Mary Earle Parker, took over Mrs. Williams’ boarding house at 282 Pearl Street. Despite the conveniences of boarding house living, it was nothing like the domestic ideal so beloved in America at this time. In The Physiology of the New York Boarding-Houses (1857), the author states, “A Boarding-House is emphatically, NOT a home.” Having grown up in a large family, Seabury perhaps welcomed the arrival of Mrs. Parker and her four children, including 17 year-old Eliza. He was 34 years old, and had been living as a boarder for approximately 15 years, which was much longer than the average length of stay for single men. According to Kenneth Scherzer in “The Unbounded Community” (1992), “A few people boarded into their late twenties and even into their thirties, but for most, boarding was simply a passing stage of the life cycle.”

Love at 282 Pearl Street

In 1814, when Seabury met Eliza Parker, he was 34 years old, well-established in his lucrative hardware business, and most likely eager to marry. And despite the assertion by the author of Boarders and Boarding House Keepers (1847) that”Landladies are … inevitably cognizant of most of the little meannesses, jealousy, and faults of their boarders – for in no place does an individual exhibit himself more completely in his true colors than in a Boarding-House,” Seabury and Eliza must have found much to admire in one another, for love soon blossomed.

| … |

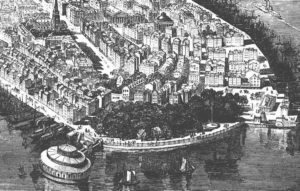

The Battery: The “Lover’s Lane” of Its Day

We can only imagine how Seabury’s courtship of Eliza played out. It must not have been easy, living under the same roof and the watchful eye of Mrs. Parker. No doubt the couple sought ways to escape the confines of the boarding house for some private moments. Most likely they walked to the Battery, a popular trysting place for lovers, where the paved walkway, the stately trees that lined the waterside, and the fresh air made it seem like an oasis from the congestion of their neighborhood. Perhaps Seabury and Eliza, from this vantage point, admired the handsome private homes that lined State Street, and talked about their future.

Another romantic spot for young couples in search of privacy was the genteel Vauxhall Garden, located between Bowery and Broadway on what is now Lafayette Street. Seabury and Eliza perhaps hired a hackney coach (for 25¢ per person), up to this bucolic garden, where they could enjoy ice cream, and music or theatrical performances. (See my post of January 2018, Vauxhall Garden: The Coney Island of Its Day).

A Wedding and a New Home

Seabury and Eliza were married on June 13, 1820, at St. George’s Episcopal Church on Chapel (now Beekman) Street. Seabury was 40 years old; his young bride was 23. (See post of June 2016, “Seabury Tredwell to Eliza Parker:” A New York City Wedding) After their wedding, Seabury, by that time a successful merchant and real estate investor, no doubt was eager to find a home for himself and his new bride; one that would provide the privacy he had long been without, and which would be large enough for a family. Most likely Seabury knew of the attractive house for sale on fashionable Dey Street through the advertisement that ran in the Evening Post from January 12 to February 3, 1820, which offered:

“The very neat two story house, No. 12 Dey street, brick front and iron railings. The house is replete with every convenience and is in excellent order.”

Seabury must have rented the house after his marriage, for the 1821 Directory lists his home address as 12 Dey Street. In the 1822 Directory, however, Seabury is listed at 34 Cedar Street, which was another boarding house, located east of Broadway near Pearl Street. It was surprising to discover that in May of 1822, an advertisement ran in the Evening Post, offering boarding to to “a few gentlemen” with “a small respectable private family” at 12 Dey Street. The ad asked that inquiries be directed to“Rev. M’Vickar, Columbia College” This no doubt was Reverend John McVickar (1787-1868), Professor of Moral Philosophy and Rhetoric at Columbia College. It is unclear why Seabury moved out, and Rev. McVickar moved in.

By 1823, Seabury and Eliza, along with their two-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, were back in the house on Dey Street. According to New York City Land Records, on April 1, 1823, Seabury purchased the house from Elizabeth Gillespie, widow of dry goods merchant George Gillespie, for $6,000. Seabury and Eliza made their home and raised their family at 12 Dey Street for 12 years, until 1835, when Seabury retired and bought the house on Fourth Street.

Moving Up in the World

Today, Dey Street today runs only two blocks, from Broadway to Church Street, but in Seabury’s day it was much longer, running all the way to West Street. Homes built on this street were brick rowhouses, typically 75-80 feet long by 25 feet wide, and therefore were large enough to accommodate a growing family. The house at 12 Dey, which was close to Broadway, had a new cistern and two grapevines in the garden. And Dey Street was on the fashionable, respectable west side of Broadway. Being the lady of the house on Dey Street was quite a social climb for Eliza, who spent her childhood in the poor Fourth Ward. In 1823, settled in their new home in the respectable, genteel part of town, Seabury and Eliza had arrived in elite society.

Sources:

- Albion, Robert Greenhalgh. The Rise of New York Port [1815-1860]. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1939.

- Bayles, William Harrison. Old Taverns of New York. New York: Frank Allaben Genealogical Company, 1915. www.gutenberg.org. Accessed 4/2/19.

- Burrows, Edwin G. And Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- City of New York. Minutes of the Common Council, May 1805. www.archive.org. Accessed 4/1/19.

- Costello, Augustine E. Our Firemen: A History of the New York Fire Departments, Volunteer and Paid. New York: Augustine E. Costello, 1887. www.archive.org. Accessed 3/15/19.

- Evening Post. July 12, 1805, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/1/19.

- Evening Post. May 13, 1812, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/2/19.

- Evening Post. January 12, 1820, p. 3. www.nespapers.com. Accessed 1/29/19.

- Evening Post. June 14, 1820, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/23/15.

- Evening Post. May 22, 1822, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/3/19.

- Gamber, Wendy. The Boardinghouse in Nineteenth Century America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

- Gunn, Thomas Butler. The Physiology of the New York Boarding-Houses. New York: Mason Brothers, 1857. www.archive.org. Accessed 3/26/19.

- Hardie, James. An Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in the City of New-York. New York: Hurtin and M’Farlane. 1799. U.S. National Library of Medicine. www.collections.nlm.nih.gov. Accessed 3/30/19.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission. Treadwell Farm Historic District, Borough of Manhattan. December 13, 1967, Calendar No. 3 LP-0536. www.s-media.nyc.gov.

- Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, and City Directory. New York: David Longworth, 1796-1835. www.digitalcollections.nypl.org.

- McAtamney, Hugh Entwistle. Cradle Days of New York (1609-1825). New York: Drew & Lewis, 1909. www.books.google.com. Accessed 4/5/19.

- Moore, William H. History of St. George’s Church, Hempstead, Long Island, N.Y. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1881. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/8/19.

- Moss, Frank. The American Metropolis: from Knickerbocker Days to the Present Time. New York: P.F. Collier, 1897. www.archive.org. Accessed 4/4/19.

- New York Land Records. Conveyances 1823 vol. 164-167. www.familysearch.org. Accessed 3/30/19.

- Scherzer, Kenneth A. The Unbounded Community: Neighborhood Life and Social Structure in New York City, 1830-1875. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992.

Another great addition to the private lives of the Tredwells. Thanks, Annie!

Such great information about the early life of Seabury and Eliza!!