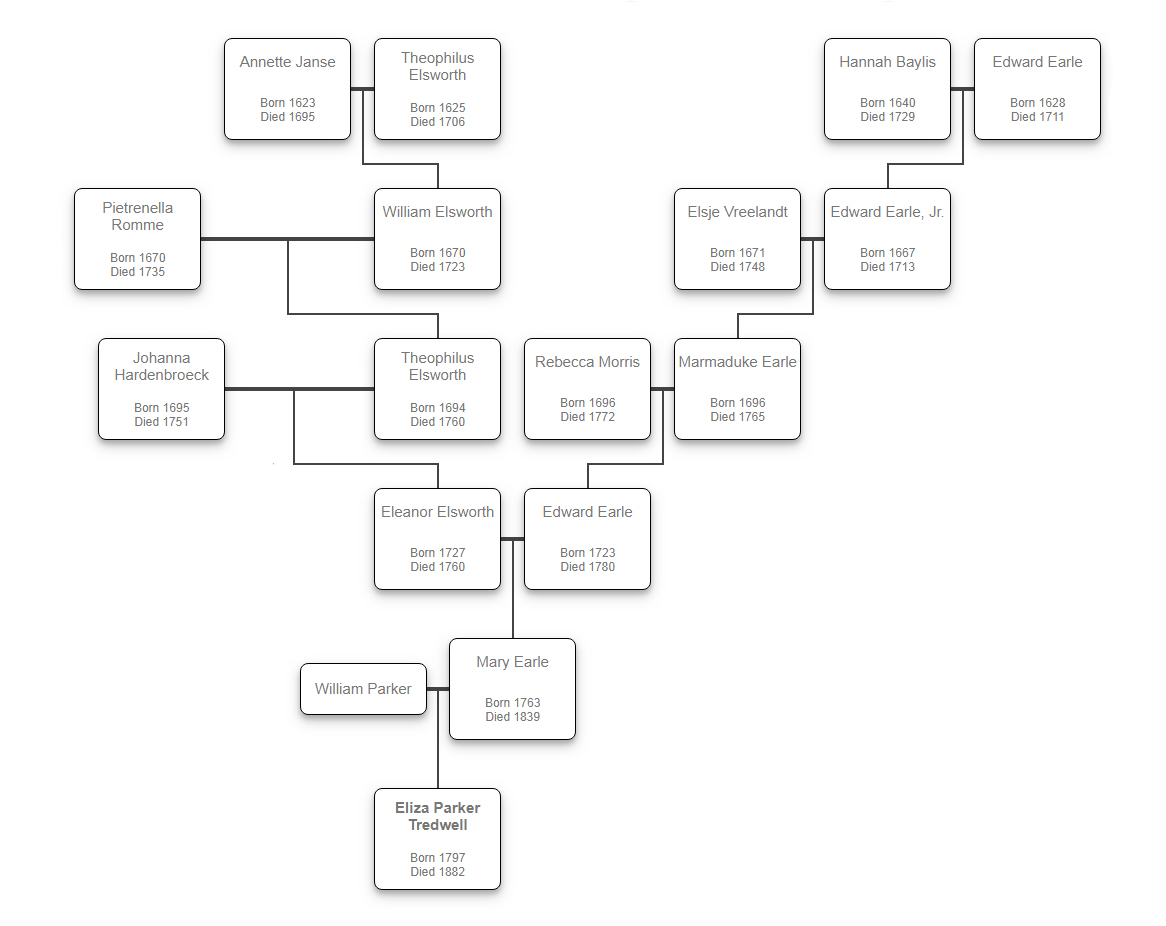

Meet the Tredwells: The Ancestry of Eliza Tredwell, Part 2

by Ann Haddad

Click here to read Part One of this post, on Eliza Tredwell’s maternal ancestry.

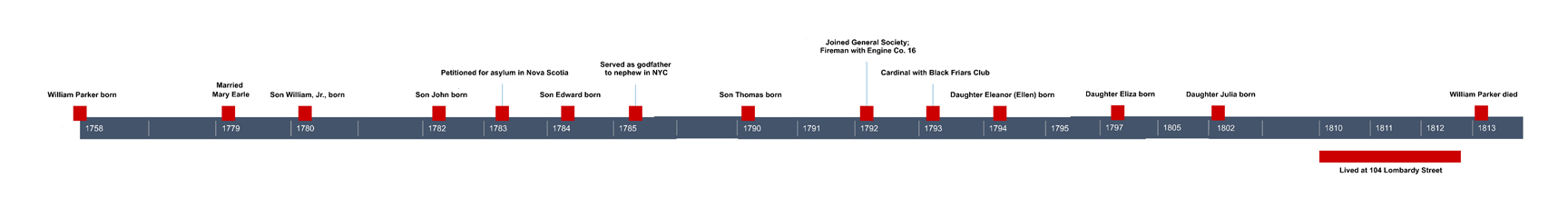

Discovering Eliza’s paternal ancestry was, and remains, a challenge, because very little was known about her father, William Parker. Aside from his name, family lore related only that he was born in England, and was a soldier in the American Revolution. Research is ongoing, but has revealed enough information about this elusive family member that we can devote an entire post to his story.

Searching for William Parker

One suspects that Eliza Parker Tredwell (1797-1882) knew very little about her father, and passed little information on to her children, for in the Nichols Family Papers at the New-York Historical Society, there are records that reveal that Gertrude herself searched for her maternal grandfather’s ancestry. In 1926, her niece Lillie Nichols paid $6 on Gertrude’s behalf to have research done at the Bureau of Vital Statistics, New Jersey Department of Health. We don’t know if Gertrude found any information on William Parker or any other relatives.

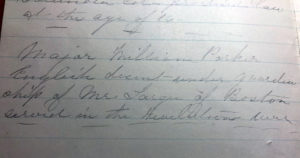

In handwritten notes in the Nichols Family Papers, Gertrude referred to William Parker as “Major,” and noted that he was “of English descent under guardianship of Mr. Larger of Boston, served in the Revolutionary War.” Other documents in the Museum archives refer to him as “Colonel” and “Captain.” There are quite a few inaccuracies in Gertrude’s notes on her ancestry (she was 86 years old at the time!), so we cannot be sure of the veracity of the information she provided on William Parker. We have not yet uncovered information on where William Parker was born, or how and when he arrived in New York City.

.

.

Loyalists in New York City

During the American Revolutionary War, New York City was under British occupation from September 1776 until November 25, 1783. Although initially a ghost town in the first year of occupation, by 1777 nearly 11,000 Loyalists (those who remained loyal to King George III) had returned from surrounding states as well as the New York hinterlands, where they had sought shelter. If William Parker was indeed of English descent, as was noted in several documents in the Museum archives, he would most likely have supported the British by either enlisting as a soldier in a Loyalist militia (as over 7,000 did in 1777 alone), or by joining a provincial unit which supplied provisions and services to the British troops.

A Double Wedding in a Garrison Town

Eliza Tredwell’s parents, William Parker and Mary Earle, married on September 19, 1779. The only way a couple could marry in the city during the occupation was if the groom was in the British Army, or if the bride and groom were Loyalists. Even the clergy were required to be Loyalists. According to “New York City During the War for Independence” (1931),

“In spite of the unsettled conditions, weddings were frequent, especially between officers of the British army and town belles. Not all who were married obtained the Governor’s license, however, because it was not uncommon, for soldiers to be married by their chaplains without such license.”

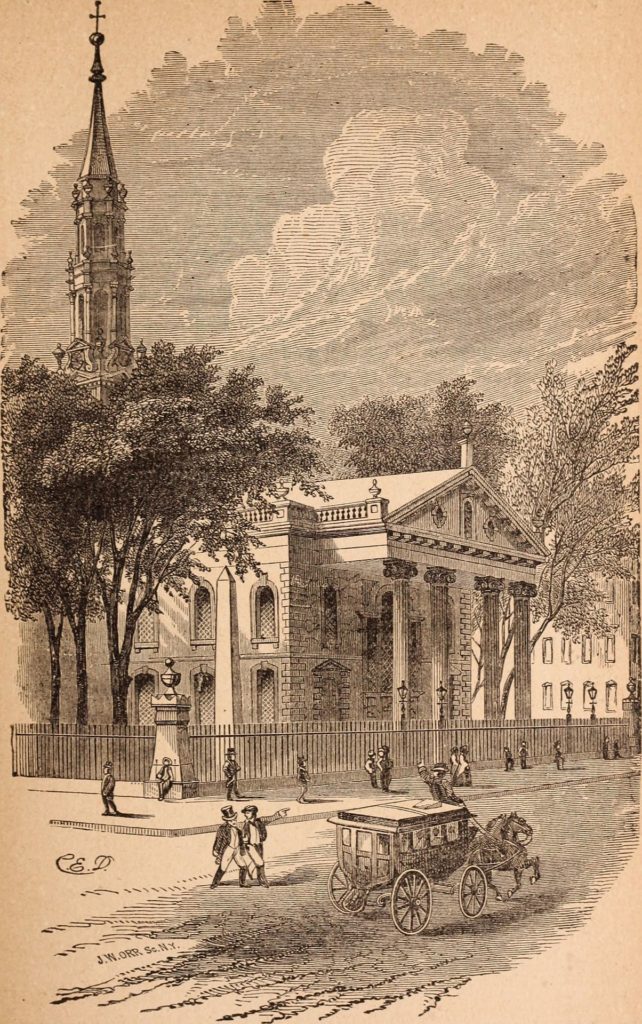

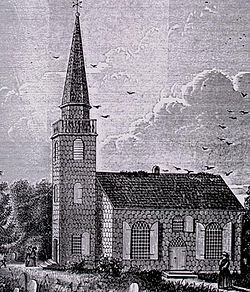

We don’t know if Mary Earle (1763-1839), Eliza Tredwell’s mother, was a “town belle” (in fact, we know nothing about her early life), but she and William Parker did obtain a marriage license from the Secretary of the Province of New York on September 14, 1779, and they were married on September 19, 1779, when Mary was 17 years of age. The ceremony most likely took place at St. Paul’s Chapel (on Broadway between Fulton and Vesey Streets), for although recorded as “Trinity Church Parish,” Trinity Church was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1776, and St. Paul’s became the primary location for worship. (Trinity Church was rebuilt in 1790.) Joining Mary and William at the altar that day was Mary’s older sister Eleanor (1753-1837), who married Thomas Laurence.

On the Road Again

| … |

Despite their allegiance to King George III, those who declared themselves Loyalists during the Revolution were treated poorly by the British. Every aspect of their lives was regulated by the ruling forces, from the food made available to them and its cost, to their living quarters. Residents were moved about town at the will of the British, as they sought to accommodate soldiers and the never ending flow of refugees. We have no knowledge as to the whereabouts of William Parker and his wife from after their marriage in 1779, to 1783. According to the Various Accounts of the British Administration of N.Y.C. During the Occupation Period, 1778-1783, from April through August 1783, William Parker, presumably with his wife and children, lived at three different addresses, all in what is now Lower Manhattan: Chatham Street (now Park Row), Fair Street (now Fulton), and Cherry Street. He must have endured financial hardship during the occupation, for his residence at Cherry Street is included in a list of “Houses Rented for Use of the Poor for 1783.”

So what exactly did William Parker do after the War? Research uncovered several clues that helped us arrive at an answer to that question.

The Post-Revolution Loyalist Exodus

Although the Revolutionary War did not formally end until the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 4, 1783, the Colonists’ victory at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781, led to an end to battle. Loyalist regiments in New York and elsewhere were gradually disbanded. New York City was reopened to Patriots, who began pouring in and demanding the restoration of their property. Loyalists had the option of remaining in the colonies and facing the ire of the Patriots, or seeking refuge in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and other Canadian provinces that were part of the British Empire. To that end, hundreds of Loyalists appealed to the Crown, in the form of petitions and memorials, in which they appealed for financial assistance, relief from hardship, and free land in Canada. It is estimated that about 42,000 Loyalists fled to Canada.

The First Clue: the Memorial of the Royal Artillery Regiment

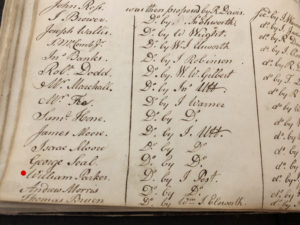

In one such memorial, Memorial of Artificers and Laborers of the Civil Branch of the Ordnance [1783], a William Parker is listed as being a member of the Royal Artillery Regiment’s group of Officers, Artificers, and Laborers, who petitioned for asylum in Nova Scotia at the War’s end. It includes the following appeal:

“That they mean only to inform His Excellency that a Sett of men who have zealously done their duty thro’ the whole course of the War, and many of them thro’ the former War, are determined to continue to do it while their services are required, and only wish an Asylum for themselves and their families, when their personal exertions are no longer necessary.”

In this document, William Parker is listed as having a wife and two children, and gives his occupation as “painter.” This concurs with what we subsequently learned about him.

![The Memorial of the Officers, Artificers, & Laborers of the Civil Branch of the Ordnance [1783]. National Archives of Great Britain, Kew. (William Parker marked in red.)](https://merchantshouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/The-Memorial.jpg)

The Memorial of the Officers, Artificers, & Laborers of the Civil Branch of the Ordnance [1783]. National Archives of Great Britain, Kew. (William Parker marked in red.)

To Nova Scotia?

It is possible that William Parker did move to Nova Scotia in 1783, and that he was back in New York City by 1785.

Mary and William Parker’s first two children, William and John, were born in 1780 and 1782, respectively. The Parker family must have been living in New York from 1780 until 1782, because William and John’s baptismal records are in the Trinity Church Register. In 1785, Mary’s sister Eleanor and her husband, Thomas Laurence, had a son, also named Thomas. Mary and William Parker must have been in New York in 1785; they served as godparents to their nephew, who was born and baptized in New York.

While we know that the Parkers were in New York from 1780 to 1782, and again in 1785, it is possible that in the intervening years the family was in Nova Scotia. Further research is required to confirm this. From his name on the Memorial, we know that William Parker wanted to go; perhaps he made the journey and returned due to hardship or family ties. Many Loyalists who left after the War trickled back in as the years went on, once the hostility ceased and the threat of retaliation dissipated.

William Parker, Jr., (1780-1812) and John Parker (1782-1827) were Eliza’s two oldest brothers; they both died relatively young. Another brother, Edward Parker (1784-1825), may have been born in Nova Scotia, as there is no record of his baptism in the Trinity Church Register, as there is with his two older brothers.

No records can be found at this time of any other Parker children born between 1784 and 1790, when Thomas Laurence Parker (1790-1881) was born. Thomas was followed by Eleanor (Ellen) Parker (1794-1855); Eliza Earle Parker (1797-1882), the future Mrs. Seabury Tredwell; and Julia Ann Parker (1802-1869).

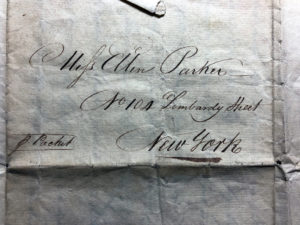

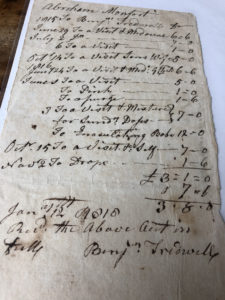

Two Letters Provide Another Clue

In the New York City Directory, a William Parker is listed as living at 104 Lombardy Street (now Monroe Street) from 1810 through 1812. His occupation is given as “painter and glazier.” In fact, William Parker, “painter and glazier,” is listed in the Directory from 1786 through 1812. In the Nichols Family Papers at the New-York Historical Society, there are two letters, dated 1810 and 1812, written to Miss Eleanor Parker, Eliza’s sister, at that same address. So we can conclude that this William Parker is indeed the father of Eliza Parker Tredwell, and, based on his occupation, that he is the same William Parker who signed the Memorial. It is interesting to note that at least three of William’s sons, John, Edward, and Thomas, became painters, likely apprenticing with their father.

.

.

.

The Wrong William Parker

Gertrude Tredwell was correct when she wrote of her grandfather William Parker as having “served in the Revolutionary War.” But she was far off the mark when she referred to him as “Major.” William Parker was not a British officer. He no doubt was a Loyalist “laborer,” who worked as a painter for the Royal Artillery. There was, however, a Major William Parker of the Royal Corps of Engineers in New York City at the same time; he had a wife and children in England, and died there after the War. Perhaps the Tredwell descendants confused this person with “our” William Parker. It is noteworthy that Mary Parker’s obituary (1839) referred to her as the wife of the “late William Parker,” with no mention of him having an official military rank.

The General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen

Further research has revealed that William Parker was initiated into the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen in 1792. This mutual aid society, founded by a group of skilled craftsmen in 1785 in New York City, served to unite mechanics and tradesmen as they sought to improve their economic situation and recover from the devastation wrought by the Revolution. A “mechanic” during this time denoted a highly skilled craftsman who either worked for himself or was employed by a merchant. William, by virtue of his occupation (painter, gilder, and glazier), clearly qualified for membership.William had been proposed for membership by Jotham Post, a butcher, member of the Common Council, and Cherry Street neighbor (William Parker lived on Cherry Street from 1792 through 1796), who, like William, was a Loyalist during the War; and Joseph Jadwin, a cooper, and one of the General Society’s founding members. Both men, in recommending William for membership, were obliged to attest to his “industry, honesty, and sobriety.”

Polly Guerin, in her 2015 history of the General Society, paints a colorful picture of the stylish attire worn by merchants and tradesmen in the late 18th century:

“In those early years the merchant class and tradesmen were stylishly dressed, sporting a cutaway tailored coat, a waist length waistcoat and knee length breeches. The adornment of wigs was de rigeur, and a tricorne hat was proper.”

Although William Parker paid his initiation fee of $5, he was struck from the register of the society in June 1793, for being in arrears of his monthly dues of 12¢.

.

.

.

William Parker, Black Friars Club Member?

It is also possible that “our” William Parker was a member of the Black Friars Club, one of the popular fraternal orders formed in New York City after the Revolution. In the New York City Register and Directory, William is listed as a Cardinal in the organization from 1793 to 1799. No further information could be found about the club, except that, according to the New York Directory and Register for 1794, it was founded in 1784 for “local, charitable and humane purposes.” It must have been of some import in the City during its heyday, for the young, rising politician DeWitt Clinton (1769-1828) gave an address at one of their meetings in November of 1794, in which he stressed the importance of benevolence.

William Parker, Fireman?

William Parker may have been involved with the New York City Fire Department for several years. In 1789 and 1790 (when there was only one William Parker listed in the New York Directory), he is listed in the New York City Register as an “affiliant” under the List of Officers Belonging to the Fire Department. In 1792, a William Parker is listed as “Fireman of Number 16” (“in Liberty Street, near the new Dutch Church”). By 1792, there were two other men by that name in the New York Directory, but it is likely that that this is “our” William Parker. William may have been recruited by his friend Jotham Post, who was a fireman of Engine Co. 2 in 1786, or perhaps by his wife Mary’s relatives (several Elsworth and Earle names are listed in the rosters).

When Did William Parker Die?

William Parker’s last entry as a “painter” in the New York City Directory appears in 1812. There is no entry for either William or Mary in the 1813 Directory. In 1814, the entry “Mary Parker, widow, boardinghouse, 282 Pearl Street” appears for the first time. This indicates that William Parker most likely died in 1812-1813, and financial necessity compelled Mary Parker to go into business for herself. Further research located a burial record in the Trinity Church Register, which indicates that a William Parker, age 55, was buried at St. Paul’s Chapel Churchyard on March 3, 1813. New York City Municipal Death Records for 1813 indicate that a William Parker died on March 4 (either of these dates could have been written in error). He lived on Greenwich Street, and the cause of death was listed as “pleurisy” (lung inflammation). If William Parker was 55 years old in 1813, he would have been born in 1758, and was 21 years of age when he wed Mary Earle. It is very likely that these records refer to our William Parker, as he and Mary were married at St. Paul’s; and both his son William Parker, who died in 1812, and his brother-in-law Thomas Laurence, who died in 1804, are buried there, as would later be his son John, who died in 1827.

Love in Mrs. Parker’s Boardinghouse

In 1814, Mrs. Parker took over the management of the boardinghouse and its occupants previously run by a Mrs. Williams at 282 Pearl Street. Seabury Tredwell was a boarder at that time; hence, that is the year he met Mrs. Parker’s 17-year-old daughter, Eliza Earle Parker. Love clearly blossomed under Mrs. Parker’s roof, for Seabury and Eliza fell in love and were married in 1820. (Click here to read “Seabury Tredwell to Eliza Parker:” A New York City Wedding.)

Mamma Moves In

Mary Parker continued to run her boardinghouse through 1822, two years after Eliza wed Seabury. In 1823, the year her son Thomas Parker married and left home, Mary Parker’s name disappears from the City Directory. It is possible that she, along with her daughter Ellen, who never married, moved in with one of her other children at that time. She died in 1839, at the home of her daughter Eliza and son-in-law Seabury Tredwell, on East 4th Street. We do not know how many years she lived with the family. Her death notice in the New York Evening Post (July 6, 1839), reads: “Friday, July 5th, Mary, relict [widow] of late William Parker, in 77th y, son Thomas L., sons in law Henry S. Thorp and Seabury Tredwell, 361-4th St.” Mary is buried in St. Mark’s Church-In-The-Bowery (at the intersection of Second Avenue and Stuyvesant and East 10th Streets), along with her daughter Ellen, who also lived with the Tredwell family for a time, and who died in 1855 at their summer home in Rumson, New Jersey.

Note: It is hoped that in a future post we will be able to provide more details about the life of William Parker.

Thanks to colleague Rich Fipphen for his assistance with this post.

Sources:

- Ancestry.com. 1790 and 1800 United States Federal Census. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Ancestry.com. History of Secaucus, New Jersey in Commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of its independence emphasizing its earlier development, 1900-1950. Secausus, N.J.: Secausus Home News, c1950. [database on-line]. Provo, UT: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005.

- Ancestry.com. Names of Persons for Whom Marriage Licenses were Issued by the Secretary of the Province of New York, Previous to 1784. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2004. Accessed 2/19/19.

- Ancestry.com. Newspaper Extractions from the Northeast, 1704-1930 [database-on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

- Ancestry.com. New York County, New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1658-1880 (NYSA) [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA; ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Ancestry.com. New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Barck, Oscar. New York City During the War for Independence. New York: Columbia University Press, 1931. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society, E173.C6.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: oxford University Press, 1999.

- Chopra, Ruma. Unnatural Rebellion: Loyalists in New York City During the Revolution. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2011.

- Costello, Augustine E. Our Firemen: A History of the New York Fire Departments, Volunteer and Paid. New York: Augustine Costello, 1887. www.babel.hathitrust,org. Accessed 3/6/19.

- Duncan, William. The New-York Directory and Register, for the Year 1794. New York: T. and J. Sword, 1794.

- Earle, Thomas, and Charles T. Congdon, eds. Annals of the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen of the City of New York, from 1785-1880. New York: The Society, 1882. www.hathitrust.org. Accessed 3/3/19.

- Evening Post. Sat., July 6, 1839, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/13/16.

- General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen of the City of New York. First Minutes of the Society, November, 1785-December, 1802.

- Guerin, Polly. The General Society of Mechanics & Tradesmen of the City of New York: A History. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015. www.books.google.com. Accessed 3/5/19.

- Great Britain, Public Record Office, Headquarters Papers of the British Army in America, PRO 30/55/87/71: 5: 9756. The Memorial of the Officers, Artificers, & Laborers of the Civil Branch of the Ordnance [1783]. National Archives of Great Britain, Kew.

- Jones, Thomas. History of New York During the Revolutionary War, Volume I. New York: The New York Historical Society, 1879, p. 114-116. www.internetarchive.org. Retrieved 3/12/16.

- Mather, Frederic Gregory. The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut. Albany, N.Y.: J.B. Lyon Co., 1913, p. 607-608. www.internetarchive.org. Accessed 5/5/16.

- New York City Registers and Directories, 1786-1840. New York Public Library. digitalcollections.nypl.org. Accessed 3/1/19.

- New York City Municipal Archives. Manhattan Death Libers, 1795-1820, Vol.1-3, March 4, 1813.

- Nichols Family Papers, 1810-1833. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Runlet, Philip. The New York Loyalists. 2nd Edition. Latham, MD: University Press of America, 2002.

- [Smith, John 1772-1786] Various Accounts of the British Administration of N.Y.C. During the occupation period, 1778-1783. BV NYC -Treasurer. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- St. George’s Episcopal Church Archives. New York, NY. Record of St. George’s Church/Baptisms 1809-1830/Marriages 1816-1837.

- Trinity Church. Trinity Church Records of Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials. www.registers.trinitywallstreet.org. Accessed 3/16/16.

- Van Buskirk, Judith L. Generous Enemies: Patriots and Loyalists in Revolutionary New York. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

- Wilson, James Grant, ed. The Memorial History of the City of New York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892 Volume II. New York: New-York History Company, 1892. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Young, Alfred F. The Democratic Republicans of New York: The Origins, 1763-1797. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1967. www.books.google.com. Accessed 3/6/19.

Meet the Tredwells: The Ancestry of Eliza Tredwell, Part 1

by Ann Haddad

In this post, the second in our “Meet the Tredwell” series, we will examine the ancestry of Eliza Earle Parker Tredwell. Part One will cover her maternal ancestry; Part Two will cover her father, William Parker.

Despite the importance of Eliza Tredwell (1797-1882), matriarch of the Tredwell family who occupied the house on East Fourth Street for nearly 100 years, little was known about her ancestry. Tracing Eliza’s maternal line was rather straightforward.

On her mother’s side, Eliza Tredwell was descended from both Dutch and English settlers.

Edward Earle, Emigrant and Landowner

Edward Earle (1628-1711), Eliza’s great-great-great grandfather, was most likely born in Great Tilse, Doncaster, Yorkshire, England. He was descended from the prominent Earle family, with branches all over England and ancestry that can be traced back to the 12th century and the reign of King Henry II. Edward probably arrived first in Barbados in or around 1635, when he was seven years old. The next record of Edward Earle, dated 1664, places him in Maryland, when he was 37 years old. Three years later, in 1667, he married Hannah Baylis (1640-c.1729); they had one son, Edward Earle, Jr., in 1667 or 1668.

After spending several years in New York City, Edward and his family settled in Secaucus, New Jersey (an inland island that was a former Dutch settlement), no later than 1673. By 1676, Edward was the owner of over 2,000 acres of land, purchased from Nicholas Bayard for “2000 Dutch Dollars,” considered to be a very large sum of money for the time. His deed of ownership refers to him as “Edward Earle of New Yorke, Planter.” Upon this land he built an estate overlooking the Hackensack River; the homestead remained in the family for more than 130 years, until 1792. According to the History of Secausus, New Jersey (1950), an assessment done in 1676, which enumerates the contents of the estate, includes among its property: “four neggro[sic] men, five christian servants.” (New Jersey abolished slavery in 1804, through a process of gradual emancipation, but some slaves were kept as late as 1865).

Edward Earle was a socially prominent and influential member of his community, and served in the House of Delegates, the English governing body of New Jersey at the time.

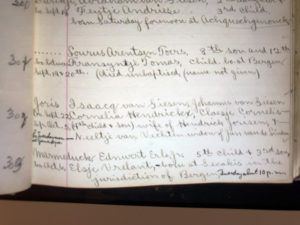

Edward Earle, Jr., Sheriff and Gentleman

Eliza’s great-great-grandfather, Edward Earle Jr. (1667 or 1668-1713), the son and only child of Edward and Hannah, was born in Maryland, and was approximately eight years old when he moved with his parents to Secaucus. Little is known of his early life. He married Elsje Vreelandt (1671-1748), who was born in what is now Jersey City, on February 13, 1688 at Reformed Dutch Church in Bergen, New Jersey. Elsje was of full Dutch descent; her parents, Enoch Vreelandt and Dircksje Meyers, were from Amsterdam. Edward and Elsje had 12 children, and lived in a stone house situated on one half of his father’s estate. Edward Earle, Jr., held many important public offices during his lifetime, including High Sheriff of Bergen County (1692), County Clerk (1693), and Coroner (1694). Like his father, he served in the House of Delegates, and was a large landowner in New Jersey. Edward, Jr., died in 1713, 18 months after his father. He was about 45 years old.

Marmaduke Earle, Freeman of New York City

Eliza’s great-grandfather, Marmaduke (an Anglo-Saxon name meaning “a mighty noble”) Earle (1696-1765), the third son of Edward, Jr., and Elsje, was born in Secaucus. He married his brother Enoch’s wife’s sister, Rebecca William Morris (1696-c.1772), daughter of William Morris and Rebecca Anderson, circa 1721. Some time around 1730, Marmaduke moved his family to New York City. By 1738, he was thoroughly established in New York. In the Memorial History of the City of New York,Volume II (1892), he is listed as being admitted in that year as a “freemen” (a person entitled to political and civil rights, including the right to vote). Marmaduke and Rebecca had six children. Nothing else is know about Marmaduke’s life or death, except that he left his entire estate to one son, Morris Earle, who was a hat maker, and with whom Marmaduke eventually lived.

.

.

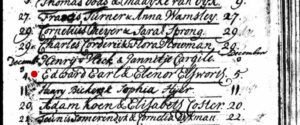

Edward Earle Marries an Elsworth

Very little is known about Edward Earle (1723-1780), Marmaduke and Rebecca’s son and Eliza’s grandfather, aside from the fact that he was born in Secaucus. Let us direct our attention to the ancestry of his wife, Eleanor Elsworth (1727-1760), Eliza Tredwell’s grandmother, whom he married on December 5, 1745, at the Dutch Reformed Church in New York City, and with whom he had six children.

Theophilus Elsworth, Mariner

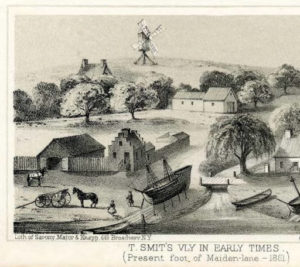

Theophilus Elsworth (c.1625-1706), Eliza Tredwell’s great-great-great grandfather, was a mariner and boat builder who was originally from Bristol, England, and who in 1652 emigrated to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam via Amsterdam. Theophilus arrived six years after Petrus Stuyvesant (1610-1672) became Director-General of the colony, which was governed by the West India Company. Stuyvesant had spent those years whipping New Amsterdam into shape by enacting many ordinances that imposed order and sanitation; he also created a municipal market to boost the town’s economy. New Amsterdam was taken by the British in 1664 and renamed New York.

While in Amsterdam, Theophilus had married Annette Janse (1623-c.1695). In New Amsterdam, they lived in what was then known as “Smits Valley” (or Vly), located on the East River between Wall Street and Maiden Lane. Theophilus and Annette had eight children.

William and Theophilus Elsworth, Shipwrights

Eliza’s great-great grandfather, Willem “William” Elsworth (1670-1723), son of Theophilus and Annette, married Pietrenella Romme (1670-1735) in New York in 1694. Their eldest son, also named Theophilus Elsworth (1694-1760), Eliza’s great-grandfather, was a shipwright like his father (according to their wills). He married Johanna Hardenbroeck (1695-after 1751) in 1716, and had six children; his third child, Eleanor Elsworth, who became the wife of Edward Earle, inherited 50 pounds sterling upon her father’s death.

Children of Edward Earle and Eleanor Elsworth

Despite Reverend Isaac Newton Earle’s assertion in “History and Genealogy of the Earles of Secausus” (1924) that “We are not able to trace the descendants of Edward any further,” we did find that Edward Earle and Eleanor Elsworth had six children. Their oldest child, Johanna, died in infancy in 1746. Hannah (1748-1829), married George Fisher, and lived in New York City near her sisters before moving to Montezuma, New York. Eleanor (1753-1837), was married to Thomas Laurence on September 19, 1779. Little is known about their next two children, Rebecca (born 1750), and Joseph (born 1756).

.

Mary Earle, Eliza Tredwell’s Mother

Mary Earle (1763-1839), Edward and Eleanor’s last child and the mother of Eliza Tredwell, was born in New York City. Little is known of her early life; of paramount importance to us is that on September 19, 1779, in a double wedding with her sister Eleanor at St. Paul’s Chapel, she married William Parker, Eliza’s father. She was 17 years old.

No doubt Eliza Tredwell was proud of her Dutch ancestors, for her youngest child, Gertrude Tredwell, was given the middle name Ellsworth (spelled with two Ls, the name having changed over the years).

Part Two of this post will focus on the story of Mary and William Parker, including recent discoveries about the life of Eliza’s father.

Sources:

- Ancestry.com. 1790 and 1800 United States Federal Census. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Ancestry.com. History of Secaucus, New Jersey in Commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of its independence emphasizing its earlier development, 1900-1950. Secausus, N.J.: Secausus Home News, c1950. [database on-line]. Provo, UT: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005.

- Ancestry.com. Newspaper Extractions from the Northeast, 1704-1930 [database-on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

- Ancestry.com. New York County, New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1658-1880 (NYSA) [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA; ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Ancestry.com. New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Ancestry.com. United States Dutch Reformed Church Records from Selected States, 1660-1926. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc. 2014. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: oxford University Press, 1999.

- Earle, Rev. Isaac Newton. History and Genealogy of the Earles of Secaucus. Marquette, Mich., Guelff Printing Company, [1924]. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 6/6/16.

- Longworth’s American Almanac, New York Register, and City Directory. New York: Thomas Longworth, [1798-1840].

- Roberts, Norma. Theophilus Ellsworth and Descendents. www.genealogy.com. Accessed 2/11/19.

- St. George’s Episcopal Church Archives. New York, NY. Record of St. George’s Church/Baptisms 1809-1830/Marriages 1816-1837.

- Trinity Church. Trinity Church Records of Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials. www.registers.trinitywallstreet.org. Accessed 3/16/16.

- Wilson, James Grant, ed. The Memorial History of the City of New York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892 Volume II. New York: New-York History Company, 1892. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/11/19.

Meet the Tredwells: The Ancestry of Seabury Tredwell

by Ann Haddad

With this post on the ancestry of Seabury Tredwell, we begin a new blog series: “Meet the Tredwells.”

A note about the variation of the spelling of Tredwell: Although early records seem to use “Tredwell” and “Treadwell” interchangeably, by the second generation in America “Tredwell” was used exclusively to denote this branch of the family. For the sake of clarity, this post will just use the spelling “Tredwell.”

In England

Seabury Tredwell’s ancestry can be traced as far back as 16th century England, to one Thomas Tredwell of Sibford Gower (before 1510-1545). His son, Alexander of Swalcliffe and Epwell (d.1603) was the father of Thomas (born c.1565). Thomas’ son Edward would leave England for the Colonies and begin the story of the Tredwell family in America.

Edward Tredwell, Emigrant

In 1635, Seabury Tredwell’s great-great-great-grandfather, Edward Tredwell (1607-1660), with his wife and two young children, emigrated from the small village of Swalcliffe, Oxfordshire, England, the seat of the prosperous Tredwell family. The family settled in the town of Ipswich, Massachusetts Bay Colony. In February 1637, the Massachusetts Bay Company granted Edward six acres of land “for planting.” Edward was one of over 20,000 emigrants who fled England for political, religious, and economic reasons, during what is known as the “Great Migration,” 1620-1640, and settled in New England.

And thus commences the story of the branch of the Tredwell family from which Seabury Tredwell (1780-1865) descended. The chronicles of this family, like the millions of others who came, and continue to come, to America, reflect the pursuit and attainment of the American Dream of peace, prosperity, and freedom.

In the ensuing years, Edward Tredwell, his wife, Sarah (nee Howes, 1609-1684), and their six children lived in the Colony of New Haven, and then Southold, on the North Fork of Long Island. By 1660, the year of his death, Edward Tredwell lived in Huntington, Long Island, then an agricultural area on the North Shore. No doubt he was a successful farmer, for upon his death his estate inventory was valued at 285 pounds sterling, a significant sum at that time.

John Tredwell, Esquire

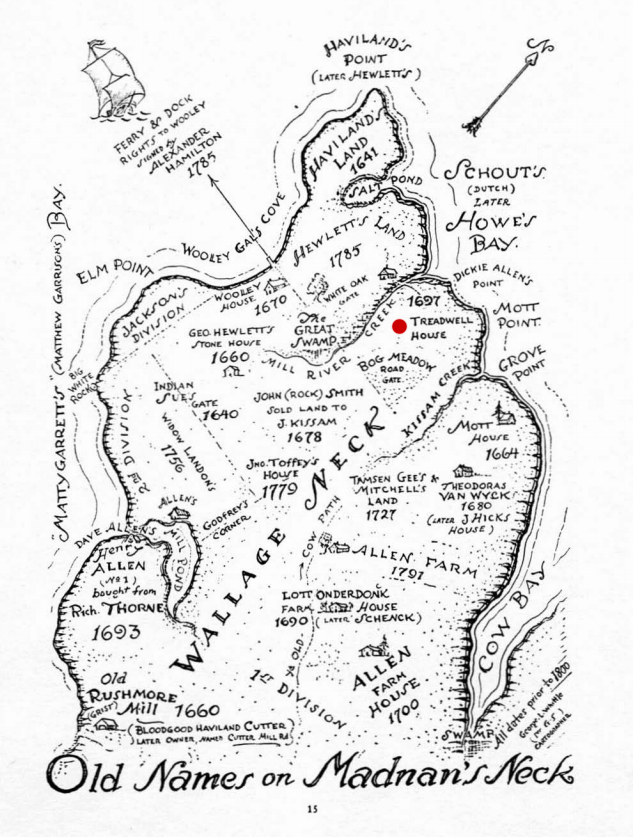

Seabury’s great-great-grandfather, John Tredwell (c.1644-before 1720), son of Edward and Sarah, moved from Huntington to Hempstead, Long Island, sometime around 1662. By 1685, John was farming 350 acres of land in Hempstead, an area known for its fertile ground, and for its abundance of wild game and fish. Throughout his adult life, John held many notable positions in the town, including assessor, county justice, auditor, constable, overseer, and surveyor. In court and civil records he was always referred to as “Gentleman” or “Esquire.” He married twice, first in 1666 or 1667 to Elizabeth Starr (who died before 1682), then to Hannah Smith (born before 1706-death unknown). In 1696, John purchased a 250-acre farm from John Kissam of Madnan’s Neck (now known as Great Neck), North Hempstead. It was the homestead of the Tredwell family for the next 100 years.

John Tredwell had two children with his first wife, Elizabeth. It is unknown if he had any children with his second wife, Hannah.

Thomas Tredwell, Captain of the Militia

Seabury’s great-grandfather, Thomas Tredwell (before 1676-1722), son of John and his first wife, Elizabeth, continued farming the land at Madnan’s Neck; like his father, he also served as a vestryman and warden of St. George’s Church in Hempstead. In 1697, he was appointed by the Governor of the Province of New York to the office of Captain of a Company of Foot in Colonel Thomas Willet’s regiment. He held this position until his death, in 1722. His wife, Hannah Denton, whom he married sometime before 1698, died in 1748. Thomas and Hannah Tredwell had eight children. Clearly the Tredwell family had become wealthier over the years, for after his death Thomas Tredwell’s estate was valued at 825 pounds sterling.

Colonel Benjamin Tredwell

Seabury’s grandfather, Benjamin Tredwell (1702-1782), son of Thomas and Hannah, married his first wife, Phebe Platt, in 1727; she died in 1738 at the age of 28 years old. In 1739 or 1740, he married Sarah Allen (1717-1782). Benjamin, like his father and grandfather before him, was a farmer and a vestryman in St. George’s Church; he would later be instrumental in the building of a new church building in Hempstead.

He served as a Major in Colonel John Cornell’s regiment of the militia, and by 1750 was ranked as Colonel. According to Henry Onderdonk, Jr., in his Queens County in Olden Times (1865), Benjamin Tredwell was described as “a gentleman who ever supported an unblemished character and was remarkable for his hospitality, cheerfulness and affability.” Benjamin died just four months after the death of his second wife, Sarah.

Benjamin had four children with his first wife, Phebe, and five with his second wife, Sarah.

.

Doctor Benjamin Tredwell, Adventurer

Seabury’s father, Benjamin Tredwell, Jr., (1735-1830), son of Benjamin and his first wife, Phebe, lived a long and eventful life in Hempstead and later in East Williston, part of the town of Westbury. In 1756, as a 22-year-old physician and surgeon (likely trained by apprenticeship), he joined a privateering expedition against the French during the Seven Years War (1756-1763) on board the ship Hercules.

Marriage to a Mayflower Descendent

Six years after completing the voyage, Dr. Benjamin Tredwell married Elizabeth Seabury (1743-1818), daughter of Reverend Samuel Seabury (1706-1764), who was rector of St. George’s Church from 1742 to 1764; her half-brother, also named Reverend Samuel Seabury (1729-1796), became the first Episcopal Bishop of the United States (see “Uncle Sam(uel): Bishop, Loyalist … Broadway Star? from July, 2016). Elizabeth’s third great-grandfather was John Alden, who with his future wife, Priscilla Mullins, arrived in the New World aboard the Mayflower in 1620.

A Loyalist Brush with the British

During the Revolutionary War, in August 1776, British troops occupied Long Island and imposed martial law. Hempstead and its Churches of England were centers of military and Loyalist life. Dr. Tredwell, a vestryman of St. George’s, was an ardent Loyalist; in fact, he was one of the signers from Queens County of the Declaration of Loyalty to the King, dated October 21, 1776. At one point during the war, he quartered Hessian soldiers at his home; this show of loyalty to the King, however, did not prevent him and many other Loyalists from being denied favor and enduring mistreatment by the British. In 1776, while riding alone, he was robbed of his valuable horse by Lieutenant-Colonel Birch, Commander of the 17th Light Dragoons. The eminent physician was sent home carrying his saddle. When he protested the injustice of the theft, Dr. Tredwell was labeled a “rebel” and threatened with arrest.

A Rabble of Rebels

Dr. Benjamin Tredwell’s wife, Elizabeth, also beloved by the community and known for her hospitality, was involved in an what must have been a frightening incident during the Revolution: on August 2, 1780, while returning from New York City in a chaise, she was robbed of her horse and money by a group of militant patriots. Her eight-year-old son, Adam, who in his adulthood became a successful fur merchant in New York City, was with her at the time. It is extremely fortunate that Mrs. Tredwell was unharmed during this incident, for one month later, on September 25, she gave birth to the eighth of her nine children, Seabury Tredwell.

Slavery and Servitude

The presence of the institution of slavery on Long Island during the 17th and 18th century is clearly documented in the historical record. Slave records exist in Long Island as early as 1683. Four generations of Seabury’s ancestors owned slaves who worked the Tredwell farms. According to the 1800 Federal census, Benjamin Tredwell, Seabury’s father, owned six slaves. Slavery was finally abolished in New York in 1827.

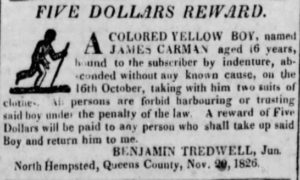

Dr. Benjamin Tredwell also hired indentured servants to work for him; indentures were legal contracts that bound a person to work for another for a specified period of years. In 1826, Benjamin Tredwell paid for an advertisement in the Long-Island Star, in which he offered $5 for the return of one James Carman, a runaway. Servitude remained legal in New York State until its abolition in 1917.

Slaves Freed

With the creation of the New York Manumission Society in 1785, abolitionist New Yorkers set about promoting the gradual manumission (release from slavery) of slaves. New York passed its first gradual emancipation law in 1799. This law provided that all children born into slavery after July 4, 1799 in the state would be freed when they turned 25 (for women) or 28 (for men). This meant that slaveholders would be able to retain their slaves during their most productive years. Slavery was finally abolished in New York in 1827.

Dr. Benjamin Tredwell legally freed three of his slaves in 1808, 1810, and 1819, by signing manumission registration certificates. The three slaves were adults at the time they received their freedom. Dr. Tredwell, along with the Overseers of the Poor of Queens County, who issued the certificates, had to guarantee that each freed person was “of sufficient abilities to provide for himself.” He retained at least one slave, however; in his Last Will and Testament, dated September 21, 1829, he bequeathed his “female slave, Cloe,” to his son Benjamin. Although this was illegal, it most likely was by mutual consent. If Cloe was incapable of supporting herself (perhaps she was elderly or disabled), this could be viewed as at act of charity. If she did not live with Benjamin’s son, her only other option, most likely, was the almshouse.

“Esteem and Confidence”

Family lore has it that on the birth of each of his children, Dr. Tredwell planted an evergreen tree in front of his house. By 1784, with the birth of his last child, George, Benjamin would have planted nine evergreen trees. All of Benjamin and Elizabeth’s children lived to adulthood.

Upon his death at the age of 95, Dr. Benjamin Tredwell’s obituary in the Long Island Telegraph and General Advertiser (June 24, 1830), stated:

“Such is said to have been the esteem and confidence of the community in this aged Physician, that to the last, he retained a large portion of the practice in the neighborhood where he resided.”

The next blog post in the series “Meet the Tredwells” will explore the fascinating story of Eliza Earle Parker Tredwell’s ancestors.

.

.

.

Sources:

- Ancestry.com. 1790 and 1800 United States Federal Census. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Ancestry.com. New York County, New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1658-1880 (NYSA) [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA; ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Ancestry.com. New York, Wills and Probate records, 1659-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Cutter, William Richard, ed. American Biography: A New Cyclopedia, Vol XL. New York: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1930, pgs. 177-178.

- Hawk, Alan J. “ArtiFacts: Benjamin Tredwell Jr.’s Amputation Knives.” Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research (2018) 476: pgs. 1715-1716. www.researchgate.net. Accessed 2/8/19.

- Hoff, Henry B. Genealogies of Long Island Families, Vol. II. From The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. Volume II. Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc, 1987.

- Jones, Thomas. History of New York During the Revolutionary War, Volume I. New York: The New York Historical Society, 1879, p. 114-116. www.internetarchive.org. Retrieved 3/12/16.

- Long-Island Star (Brooklyn, New York) 23 November, 1826, Thursday, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Luke, Dr. Myron H. Vignettes of Hempstead Town 1643-1800. Hempstead, New York: Long Island Studies Institute, 1993.

- Mather, Frederic Gregory. The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut. Albany, N.Y.: J.B. Lyon Co., 1913, p. 607-608. www.internetarchive.org. Retrieved 5/5/16.

- Moore, William H. History of St. George’s Church, Hempstead, Long Island, N.Y. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1881. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/8/19.

- Onderdonk, Jr., Henry. Documents and Letters Intended to Illustrate the Revolutionary Incidents of Queens County. New York: Levitt, Trow and Company, 1846., p. 117-128, p. 172-173, p. 244-249. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Robbins, William A. “Descendants of Edward Tre[a]dwell Through His Son John.” The New York Genealogical & Biographical Record. April, 1912 (Volume 43, No. 2), p. 127; Ibid., July, 1912, (Volume 43, No. 3), p. 221; Ibid., Oct, 1912 (Volume 43, No. 4). www.archive.org. Accessed 2/8/19.

- Smith, Dean Crawford. The Ancestry of Eva Belle Kempton, 1878-1908, Part II: The Ancestry of Amanda Spiller 1823-1873. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2008.

- St. George’s Episcopal Church Archives. New York, NY. Record of St. George’s Church/Baptisms 1809-1830/Marriages 1816-1837.

- Treadwell, Thomas Alanson. “Tredwells in Search of Tredwells: Adventures in Ancestry.” New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, 104, No. 4 (1973): 195-204.

- Tredwell, Thomas Allison., “Tredwells in Search of Tredwells” in New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, 104 (1973): 195-204.

- Wilson, James Grant, ed. The Memorial History of the City of New York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892 Volume II. New York: New-York History Company, 1892. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/11/19.