Plaster Walls and Ceilings

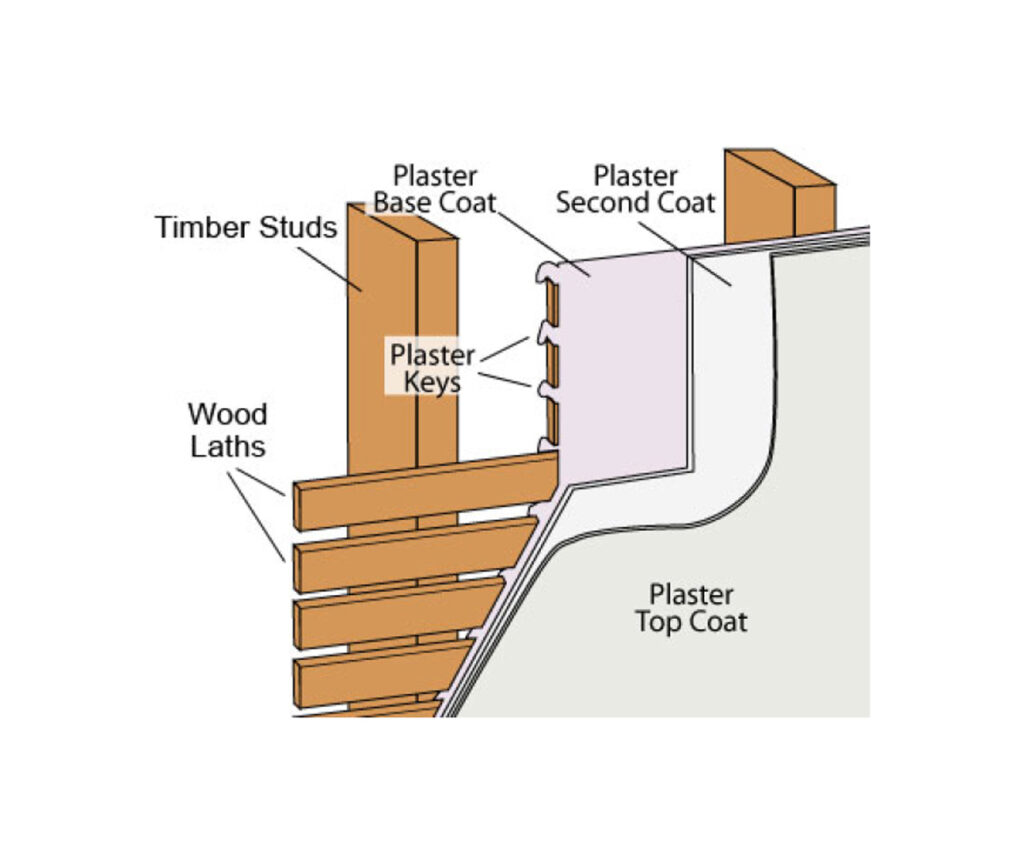

Plaster was ideal for walls and ceilings because it was strong, durable, and fire resistant. It also reduced sound between rooms. Walls and ceilings were generally 1 1⁄2” thick and required three coats of plaster.

- For the first coat, called the “scratch coat,” the plaster was made of a combination of clay, the minerals gypsum and lime, and sand, with animal hair used as a reinforcing binder. The plaster was gently pressed onto and between the wood laths (thin strips of wood with spaces between nailed at right angles to wall studs or ceiling joists). Pushed between the laths, the moist plaster slumped over the back, forming “keys,” which held the heavy plaster in place. The plaster was applied with a “darby,” a long wooden trowel-like tool.

- A second layer of plaster, called the “brown coat,” was applied to build up the wall and ceiling thickness and to provide a uniform surface for the finish plaster. The “brown coat” was made of the same mixture of materials as the “scratch coat.”

- For the final coat, lime was mixed with water and fine sand, but no hair, to form lime putty. Gypsum – used to speed curing – was added to the putty just before application. The finish plaster, which was applied with a trowel, was generally less than 1⁄4” thick, and gave the walls and ceilings a smooth, white surface finish. Plaster walls typically required 40 days to cure before they could be painted or wallpapered.

In 1831-32, 19 plasterers were listed in the New York City Directory. They were highly trained craftsmen. The quality of their work determined the durability of the plaster. The proper mix, application, thickness, and curing were all essential factors.

|

|

|