Meet the Tredwells: The Ancestry of Eliza Tredwell, Part 2

by Ann Haddad

Click here to read Part One of this post, on Eliza Tredwell’s maternal ancestry.

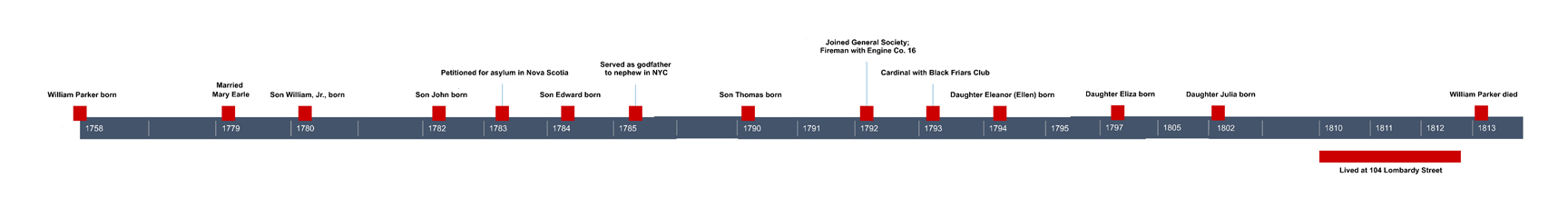

Discovering Eliza’s paternal ancestry was, and remains, a challenge, because very little was known about her father, William Parker. Aside from his name, family lore related only that he was born in England, and was a soldier in the American Revolution. Research is ongoing, but has revealed enough information about this elusive family member that we can devote an entire post to his story.

Searching for William Parker

One suspects that Eliza Parker Tredwell (1797-1882) knew very little about her father, and passed little information on to her children, for in the Nichols Family Papers at the New-York Historical Society, there are records that reveal that Gertrude herself searched for her maternal grandfather’s ancestry. In 1926, her niece Lillie Nichols paid $6 on Gertrude’s behalf to have research done at the Bureau of Vital Statistics, New Jersey Department of Health. We don’t know if Gertrude found any information on William Parker or any other relatives.

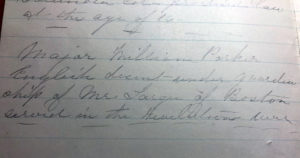

In handwritten notes in the Nichols Family Papers, Gertrude referred to William Parker as “Major,” and noted that he was “of English descent under guardianship of Mr. Larger of Boston, served in the Revolutionary War.” Other documents in the Museum archives refer to him as “Colonel” and “Captain.” There are quite a few inaccuracies in Gertrude’s notes on her ancestry (she was 86 years old at the time!), so we cannot be sure of the veracity of the information she provided on William Parker. We have not yet uncovered information on where William Parker was born, or how and when he arrived in New York City.

.

.

Loyalists in New York City

During the American Revolutionary War, New York City was under British occupation from September 1776 until November 25, 1783. Although initially a ghost town in the first year of occupation, by 1777 nearly 11,000 Loyalists (those who remained loyal to King George III) had returned from surrounding states as well as the New York hinterlands, where they had sought shelter. If William Parker was indeed of English descent, as was noted in several documents in the Museum archives, he would most likely have supported the British by either enlisting as a soldier in a Loyalist militia (as over 7,000 did in 1777 alone), or by joining a provincial unit which supplied provisions and services to the British troops.

A Double Wedding in a Garrison Town

Eliza Tredwell’s parents, William Parker and Mary Earle, married on September 19, 1779. The only way a couple could marry in the city during the occupation was if the groom was in the British Army, or if the bride and groom were Loyalists. Even the clergy were required to be Loyalists. According to “New York City During the War for Independence” (1931),

“In spite of the unsettled conditions, weddings were frequent, especially between officers of the British army and town belles. Not all who were married obtained the Governor’s license, however, because it was not uncommon, for soldiers to be married by their chaplains without such license.”

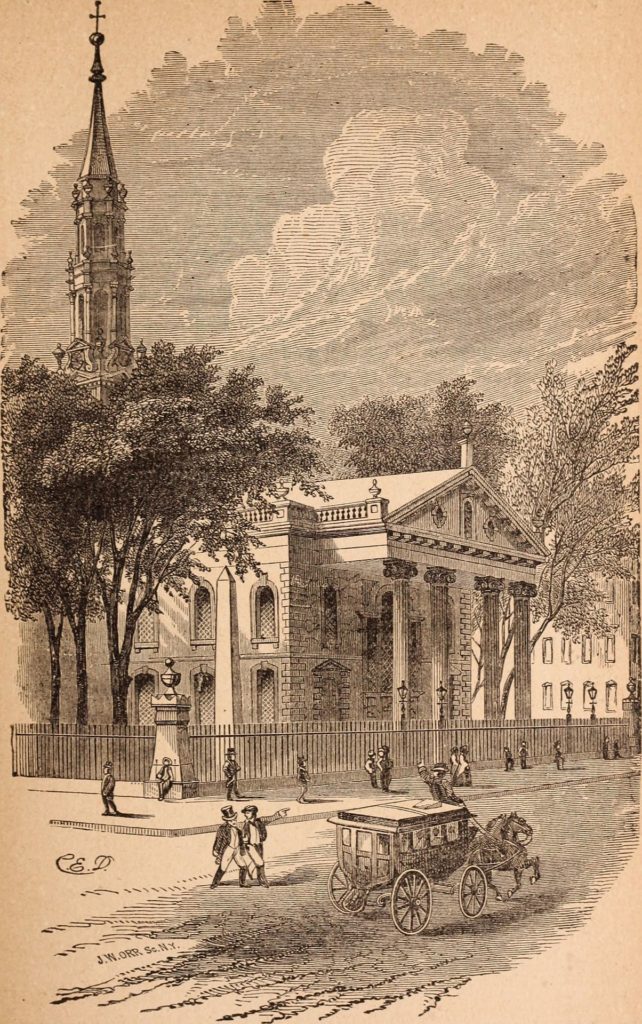

We don’t know if Mary Earle (1763-1839), Eliza Tredwell’s mother, was a “town belle” (in fact, we know nothing about her early life), but she and William Parker did obtain a marriage license from the Secretary of the Province of New York on September 14, 1779, and they were married on September 19, 1779, when Mary was 17 years of age. The ceremony most likely took place at St. Paul’s Chapel (on Broadway between Fulton and Vesey Streets), for although recorded as “Trinity Church Parish,” Trinity Church was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1776, and St. Paul’s became the primary location for worship. (Trinity Church was rebuilt in 1790.) Joining Mary and William at the altar that day was Mary’s older sister Eleanor (1753-1837), who married Thomas Laurence.

On the Road Again

| … |

Despite their allegiance to King George III, those who declared themselves Loyalists during the Revolution were treated poorly by the British. Every aspect of their lives was regulated by the ruling forces, from the food made available to them and its cost, to their living quarters. Residents were moved about town at the will of the British, as they sought to accommodate soldiers and the never ending flow of refugees. We have no knowledge as to the whereabouts of William Parker and his wife from after their marriage in 1779, to 1783. According to the Various Accounts of the British Administration of N.Y.C. During the Occupation Period, 1778-1783, from April through August 1783, William Parker, presumably with his wife and children, lived at three different addresses, all in what is now Lower Manhattan: Chatham Street (now Park Row), Fair Street (now Fulton), and Cherry Street. He must have endured financial hardship during the occupation, for his residence at Cherry Street is included in a list of “Houses Rented for Use of the Poor for 1783.”

So what exactly did William Parker do after the War? Research uncovered several clues that helped us arrive at an answer to that question.

The Post-Revolution Loyalist Exodus

Although the Revolutionary War did not formally end until the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 4, 1783, the Colonists’ victory at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781, led to an end to battle. Loyalist regiments in New York and elsewhere were gradually disbanded. New York City was reopened to Patriots, who began pouring in and demanding the restoration of their property. Loyalists had the option of remaining in the colonies and facing the ire of the Patriots, or seeking refuge in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and other Canadian provinces that were part of the British Empire. To that end, hundreds of Loyalists appealed to the Crown, in the form of petitions and memorials, in which they appealed for financial assistance, relief from hardship, and free land in Canada. It is estimated that about 42,000 Loyalists fled to Canada.

The First Clue: the Memorial of the Royal Artillery Regiment

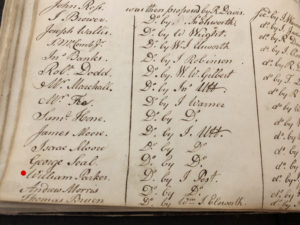

In one such memorial, Memorial of Artificers and Laborers of the Civil Branch of the Ordnance [1783], a William Parker is listed as being a member of the Royal Artillery Regiment’s group of Officers, Artificers, and Laborers, who petitioned for asylum in Nova Scotia at the War’s end. It includes the following appeal:

“That they mean only to inform His Excellency that a Sett of men who have zealously done their duty thro’ the whole course of the War, and many of them thro’ the former War, are determined to continue to do it while their services are required, and only wish an Asylum for themselves and their families, when their personal exertions are no longer necessary.”

In this document, William Parker is listed as having a wife and two children, and gives his occupation as “painter.” This concurs with what we subsequently learned about him.

![The Memorial of the Officers, Artificers, & Laborers of the Civil Branch of the Ordnance [1783]. National Archives of Great Britain, Kew. (William Parker marked in red.)](https://merchantshouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/The-Memorial.jpg)

The Memorial of the Officers, Artificers, & Laborers of the Civil Branch of the Ordnance [1783]. National Archives of Great Britain, Kew. (William Parker marked in red.)

To Nova Scotia?

It is possible that William Parker did move to Nova Scotia in 1783, and that he was back in New York City by 1785.

Mary and William Parker’s first two children, William and John, were born in 1780 and 1782, respectively. The Parker family must have been living in New York from 1780 until 1782, because William and John’s baptismal records are in the Trinity Church Register. In 1785, Mary’s sister Eleanor and her husband, Thomas Laurence, had a son, also named Thomas. Mary and William Parker must have been in New York in 1785; they served as godparents to their nephew, who was born and baptized in New York.

While we know that the Parkers were in New York from 1780 to 1782, and again in 1785, it is possible that in the intervening years the family was in Nova Scotia. Further research is required to confirm this. From his name on the Memorial, we know that William Parker wanted to go; perhaps he made the journey and returned due to hardship or family ties. Many Loyalists who left after the War trickled back in as the years went on, once the hostility ceased and the threat of retaliation dissipated.

William Parker, Jr., (1780-1812) and John Parker (1782-1827) were Eliza’s two oldest brothers; they both died relatively young. Another brother, Edward Parker (1784-1825), may have been born in Nova Scotia, as there is no record of his baptism in the Trinity Church Register, as there is with his two older brothers.

No records can be found at this time of any other Parker children born between 1784 and 1790, when Thomas Laurence Parker (1790-1881) was born. Thomas was followed by Eleanor (Ellen) Parker (1794-1855); Eliza Earle Parker (1797-1882), the future Mrs. Seabury Tredwell; and Julia Ann Parker (1802-1869).

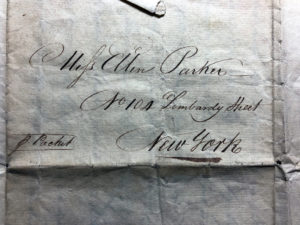

Two Letters Provide Another Clue

In the New York City Directory, a William Parker is listed as living at 104 Lombardy Street (now Monroe Street) from 1810 through 1812. His occupation is given as “painter and glazier.” In fact, William Parker, “painter and glazier,” is listed in the Directory from 1786 through 1812. In the Nichols Family Papers at the New-York Historical Society, there are two letters, dated 1810 and 1812, written to Miss Eleanor Parker, Eliza’s sister, at that same address. So we can conclude that this William Parker is indeed the father of Eliza Parker Tredwell, and, based on his occupation, that he is the same William Parker who signed the Memorial. It is interesting to note that at least three of William’s sons, John, Edward, and Thomas, became painters, likely apprenticing with their father.

.

.

.

The Wrong William Parker

Gertrude Tredwell was correct when she wrote of her grandfather William Parker as having “served in the Revolutionary War.” But she was far off the mark when she referred to him as “Major.” William Parker was not a British officer. He no doubt was a Loyalist “laborer,” who worked as a painter for the Royal Artillery. There was, however, a Major William Parker of the Royal Corps of Engineers in New York City at the same time; he had a wife and children in England, and died there after the War. Perhaps the Tredwell descendants confused this person with “our” William Parker. It is noteworthy that Mary Parker’s obituary (1839) referred to her as the wife of the “late William Parker,” with no mention of him having an official military rank.

The General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen

Further research has revealed that William Parker was initiated into the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen in 1792. This mutual aid society, founded by a group of skilled craftsmen in 1785 in New York City, served to unite mechanics and tradesmen as they sought to improve their economic situation and recover from the devastation wrought by the Revolution. A “mechanic” during this time denoted a highly skilled craftsman who either worked for himself or was employed by a merchant. William, by virtue of his occupation (painter, gilder, and glazier), clearly qualified for membership.William had been proposed for membership by Jotham Post, a butcher, member of the Common Council, and Cherry Street neighbor (William Parker lived on Cherry Street from 1792 through 1796), who, like William, was a Loyalist during the War; and Joseph Jadwin, a cooper, and one of the General Society’s founding members. Both men, in recommending William for membership, were obliged to attest to his “industry, honesty, and sobriety.”

Polly Guerin, in her 2015 history of the General Society, paints a colorful picture of the stylish attire worn by merchants and tradesmen in the late 18th century:

“In those early years the merchant class and tradesmen were stylishly dressed, sporting a cutaway tailored coat, a waist length waistcoat and knee length breeches. The adornment of wigs was de rigeur, and a tricorne hat was proper.”

Although William Parker paid his initiation fee of $5, he was struck from the register of the society in June 1793, for being in arrears of his monthly dues of 12¢.

.

.

.

William Parker, Black Friars Club Member?

It is also possible that “our” William Parker was a member of the Black Friars Club, one of the popular fraternal orders formed in New York City after the Revolution. In the New York City Register and Directory, William is listed as a Cardinal in the organization from 1793 to 1799. No further information could be found about the club, except that, according to the New York Directory and Register for 1794, it was founded in 1784 for “local, charitable and humane purposes.” It must have been of some import in the City during its heyday, for the young, rising politician DeWitt Clinton (1769-1828) gave an address at one of their meetings in November of 1794, in which he stressed the importance of benevolence.

William Parker, Fireman?

William Parker may have been involved with the New York City Fire Department for several years. In 1789 and 1790 (when there was only one William Parker listed in the New York Directory), he is listed in the New York City Register as an “affiliant” under the List of Officers Belonging to the Fire Department. In 1792, a William Parker is listed as “Fireman of Number 16” (“in Liberty Street, near the new Dutch Church”). By 1792, there were two other men by that name in the New York Directory, but it is likely that that this is “our” William Parker. William may have been recruited by his friend Jotham Post, who was a fireman of Engine Co. 2 in 1786, or perhaps by his wife Mary’s relatives (several Elsworth and Earle names are listed in the rosters).

When Did William Parker Die?

William Parker’s last entry as a “painter” in the New York City Directory appears in 1812. There is no entry for either William or Mary in the 1813 Directory. In 1814, the entry “Mary Parker, widow, boardinghouse, 282 Pearl Street” appears for the first time. This indicates that William Parker most likely died in 1812-1813, and financial necessity compelled Mary Parker to go into business for herself. Further research located a burial record in the Trinity Church Register, which indicates that a William Parker, age 55, was buried at St. Paul’s Chapel Churchyard on March 3, 1813. New York City Municipal Death Records for 1813 indicate that a William Parker died on March 4 (either of these dates could have been written in error). He lived on Greenwich Street, and the cause of death was listed as “pleurisy” (lung inflammation). If William Parker was 55 years old in 1813, he would have been born in 1758, and was 21 years of age when he wed Mary Earle. It is very likely that these records refer to our William Parker, as he and Mary were married at St. Paul’s; and both his son William Parker, who died in 1812, and his brother-in-law Thomas Laurence, who died in 1804, are buried there, as would later be his son John, who died in 1827.

Love in Mrs. Parker’s Boardinghouse

In 1814, Mrs. Parker took over the management of the boardinghouse and its occupants previously run by a Mrs. Williams at 282 Pearl Street. Seabury Tredwell was a boarder at that time; hence, that is the year he met Mrs. Parker’s 17-year-old daughter, Eliza Earle Parker. Love clearly blossomed under Mrs. Parker’s roof, for Seabury and Eliza fell in love and were married in 1820. (Click here to read “Seabury Tredwell to Eliza Parker:” A New York City Wedding.)

Mamma Moves In

Mary Parker continued to run her boardinghouse through 1822, two years after Eliza wed Seabury. In 1823, the year her son Thomas Parker married and left home, Mary Parker’s name disappears from the City Directory. It is possible that she, along with her daughter Ellen, who never married, moved in with one of her other children at that time. She died in 1839, at the home of her daughter Eliza and son-in-law Seabury Tredwell, on East 4th Street. We do not know how many years she lived with the family. Her death notice in the New York Evening Post (July 6, 1839), reads: “Friday, July 5th, Mary, relict [widow] of late William Parker, in 77th y, son Thomas L., sons in law Henry S. Thorp and Seabury Tredwell, 361-4th St.” Mary is buried in St. Mark’s Church-In-The-Bowery (at the intersection of Second Avenue and Stuyvesant and East 10th Streets), along with her daughter Ellen, who also lived with the Tredwell family for a time, and who died in 1855 at their summer home in Rumson, New Jersey.

Note: It is hoped that in a future post we will be able to provide more details about the life of William Parker.

Thanks to colleague Rich Fipphen for his assistance with this post.

Sources:

- Ancestry.com. 1790 and 1800 United States Federal Census. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Ancestry.com. History of Secaucus, New Jersey in Commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of its independence emphasizing its earlier development, 1900-1950. Secausus, N.J.: Secausus Home News, c1950. [database on-line]. Provo, UT: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2005.

- Ancestry.com. Names of Persons for Whom Marriage Licenses were Issued by the Secretary of the Province of New York, Previous to 1784. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2004. Accessed 2/19/19.

- Ancestry.com. Newspaper Extractions from the Northeast, 1704-1930 [database-on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

- Ancestry.com. New York County, New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1658-1880 (NYSA) [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA; ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Ancestry.com. New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Barck, Oscar. New York City During the War for Independence. New York: Columbia University Press, 1931. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society, E173.C6.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: oxford University Press, 1999.

- Chopra, Ruma. Unnatural Rebellion: Loyalists in New York City During the Revolution. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2011.

- Costello, Augustine E. Our Firemen: A History of the New York Fire Departments, Volunteer and Paid. New York: Augustine Costello, 1887. www.babel.hathitrust,org. Accessed 3/6/19.

- Duncan, William. The New-York Directory and Register, for the Year 1794. New York: T. and J. Sword, 1794.

- Earle, Thomas, and Charles T. Congdon, eds. Annals of the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen of the City of New York, from 1785-1880. New York: The Society, 1882. www.hathitrust.org. Accessed 3/3/19.

- Evening Post. Sat., July 6, 1839, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/13/16.

- General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen of the City of New York. First Minutes of the Society, November, 1785-December, 1802.

- Guerin, Polly. The General Society of Mechanics & Tradesmen of the City of New York: A History. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015. www.books.google.com. Accessed 3/5/19.

- Great Britain, Public Record Office, Headquarters Papers of the British Army in America, PRO 30/55/87/71: 5: 9756. The Memorial of the Officers, Artificers, & Laborers of the Civil Branch of the Ordnance [1783]. National Archives of Great Britain, Kew.

- Jones, Thomas. History of New York During the Revolutionary War, Volume I. New York: The New York Historical Society, 1879, p. 114-116. www.internetarchive.org. Retrieved 3/12/16.

- Mather, Frederic Gregory. The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut. Albany, N.Y.: J.B. Lyon Co., 1913, p. 607-608. www.internetarchive.org. Accessed 5/5/16.

- New York City Registers and Directories, 1786-1840. New York Public Library. digitalcollections.nypl.org. Accessed 3/1/19.

- New York City Municipal Archives. Manhattan Death Libers, 1795-1820, Vol.1-3, March 4, 1813.

- Nichols Family Papers, 1810-1833. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Runlet, Philip. The New York Loyalists. 2nd Edition. Latham, MD: University Press of America, 2002.

- [Smith, John 1772-1786] Various Accounts of the British Administration of N.Y.C. During the occupation period, 1778-1783. BV NYC -Treasurer. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- St. George’s Episcopal Church Archives. New York, NY. Record of St. George’s Church/Baptisms 1809-1830/Marriages 1816-1837.

- Trinity Church. Trinity Church Records of Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials. www.registers.trinitywallstreet.org. Accessed 3/16/16.

- Van Buskirk, Judith L. Generous Enemies: Patriots and Loyalists in Revolutionary New York. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

- Wilson, James Grant, ed. The Memorial History of the City of New York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892 Volume II. New York: New-York History Company, 1892. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Young, Alfred F. The Democratic Republicans of New York: The Origins, 1763-1797. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1967. www.books.google.com. Accessed 3/6/19.

Amazing work as always! So many great tidbits but I think my favorite is that Gertrude was also looking for answers, and at 86! Gives us some great insight into her later life as well.

It must have been quite a shift for Eliza from her upbringing to running an elaborate household and managing servants!

Thanks, Jackie! Yes, it probably was a bit daunting for Eliza. But she had servants to help her, and she no doubt learned from her mother Mary Parker, who ran a boarding house! Imagine what that mist have been like? I’d wager that Eliza and her sisters Eleanor (“Aunt Ellen”) and Julia helped their mother. Eliza was 16 when her mother took over the job and was in the house until she was 23. That’s plenty of time to learn the ins and outs of domestic economy.

So now we know what happened to Eliza’s father and why her mother took over the boarding house! As a recent widow she did what so many other women in her circumstances did. This research is so valuable and so difficult. Annie, you are to be congratulated for this contribution to the standing of the Merchant’s House–makes it even more important as a historic document to have documented evidence of its residents!

Thank you, Mary! There’s is so much more research to be done on William Parker’s early life -was he indeed born in England, when did he arrive in the colonies, and how did he wind up in NYC? And, the most romantic question, how did he meet Mary Earle?

Outstanding work in every way, Annie. All of the information is valuable, and I am particularly drawn to the fact that Mary Parker is buried at St. Mark’s Church-in-The-Bowery. St. Mark’s is a key element in the MHM Noho walking tour, for while we do not visit the church, we describe it while at the corner of Astor Place and Cooper Square West. Part of the description is devoted to naming the prominent New Yorkers buried there, especially Peter Stuyvesant himself. Others, according to the church’s web site, include Philip Hone, Daniel Tompkins, and A. T. Stewart. The direct connection to the Tredwell family adds a wonderful touch.