Nature for Ladies: The Victorian Art of Flower & Seaweed Pressing

by Ann Haddad

Escaping the Summer Heat

As city dwellers do today, many 19th century New Yorkers desired to escape the wretched summer heat and humidity by retreating to the seaside or country for the fresh air and cooler temperatures. For the Tredwells, that usually meant traveling to Rumson, New Jersey, where they relaxed at their 850-acre farm near the ocean. But the summer of 1865 must have been a difficult time for the family. Their grief over the loss of Seabury Tredwell in March surely was still fresh, and they were only four months into their one-year mourning period.

A Change of Scenery

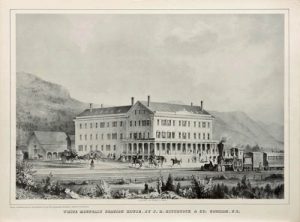

Perhaps that is why, in July 1865, 24-year-old Gertrude, no doubt along with other family members, chose a new destination. Instead of, or in addition to, summering in Rumson, they ventured to both the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and Northampton, Massachusetts. Popular tourist attractions in the mid-to-late 19th century, the White Mountains in particular drew many celebrated visitors, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, painter Thomas Cole, and Mary Todd Lincoln who, along with her son Robert, journeyed there in 1863. Northampton was called the “loveliest village of America” by The New York Times in 1865.

A Long Journey

Gertrude and her entourage could have taken two routes to reach the White Mountains. One was to hire a carriage to bring them to Peck Slip on the East River in lower Manhattan. There they would board the 3:15 p.m. steamer and travel to New Haven, Connecticut, then switch to the New Haven Railroad and later, a stagecoach, which would bring them to the White Mountains. Or, the carriage driver may have been directed to the New Haven Railroad depot at Fourth Avenue and 27th Street, where the group would board the 12:15 p.m. train and travel exclusively by rail. Either way, the day-long journey necessitated an overnight lodging, usually in Springfield, Massachusetts.

After spending a week or two enjoying the beauty of nature in the White Mountains, Gertrude and her fellow travelers made the return trip by rail, stopping for a time in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she and her party ascended Mt. Holyoke. Here she enjoyed another idyllic mountain scene, and the quiet beauty of the Connecticut River Valley, before returning home.

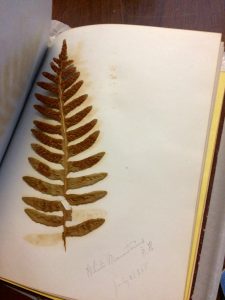

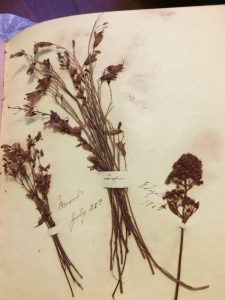

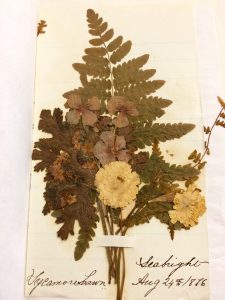

A Bounty in the Archives

How do we know for certain that Gertrude visited the White Mountains and Northampton in July 1865? The Tredwell Archives at the Merchant’s House Museum contain a large collection of pressed flowers and seaweed, both mounted in scrapbooks and on loose leaves, dating from 1858 to 1876. The scrapbooks bear Gertrude’s name and she made notations on several of the pages indicating where the specimens were obtained, such as “Mt. Holyoke,” “Northampton,” and “White Mountains.” They were dated either July 1865, or July 20, 1865.

- (Click images to enlarge.)

Mother-Daughter Time

We are not certain if all of the pressings in the extraordinary collection were made by Gertrude. Her sisters may also have enjoyed the hobby. But we do know that both scrapbooks of pressed flowers, ferns, and seaweed bear her name; and many individual pages bear the initials “E.T,” and “E.E.T.” This can only be Gertrude’s mother, Eliza Earle Tredwell. Perhaps Gertrude developed her obvious passion for the craft from her mother; it may have been an activity they pursued and delighted in together.

A Victorian Pastime

In the mid-19th century, flower pressing emerged as one of the most popular pastimes for Victorian middle and upper class women. With plenty of time on their hands, and no dearth of resources, they sought to explore their artistic side in unique ways. Wishing to be part of the skyrocketing craze for natural history at that time, yet restricted by virtue of their sex, many women found the art of identifying and collecting plant specimens to be a respectable way of examining the natural world, improving their scientific knowledge, and preserving the beauty around them. It became an acceptable way for women to merge the natural world with the domestic one; respect for nature was also viewed as a Christian road to God. A woman given to this pastime would pride herself on her “herbarium,” or collection of flora.

Women also pressed flowers for sentimental and romantic reasons. The flora pressed into a book or album served as a remembrance of a particular person or event; for Gertrude, her scrapbook also served in part as a travel log.

.

.

A Kindred Spirit

One well-known herbarium maker was the poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), who as a young girl pressed many specimens into a bound album, much like the ones created by Gertrude. In an 1845 letter to a friend, Emily wrote, “Have you made an herbarium yet? I hope you will if you have not, it would be such a treasure to you; most all the girls are making one.”

It is pleasant to imagine Gertrude and Emily (who lived only 10 miles away in Amherst) meeting on Mt. Holyoke as they pursued their shared passion!

How It Was Done

In order to maintain the freshness and vibrant color of the florals, Gertrude or Eliza purchased a wooden field press. Many stationers quickly caught on to the popularity of the hobby and rushed to stock presses and other needed supplies, such as paper and glue. For those who desired to learn the craft, popular magazines often published instructions, especially in the fall when the brilliant colors of the autumn foliage would inspire collecting.

Picking the flowers late in the afternoon ensured that all the dew had dried. They were then placed between sheets of blotting paper and pressed with a crank or straps to tighten and flatten the specimen. Once dried, the flowers were glued, sewn, or attached onto paper (which was plentiful and inexpensive during the Industrial Revolution), silk, velvet, or other fabric. Gertrude kept hers in a scrapbook; framing under glass was also a popular way to exhibit one’s work. Or the flowers could be pressed between the pages of a beloved book or family Bible.

Many of the specimens in the Merchant’s House Museum collection are of delicate, intricately-patterned seaweed, probably gathered at the shore in New Jersey. Readily available, especially for women who spent summers at the seaside, seaweed emits a sticky, gelatinous substance when pressed, thereby eliminating the need for glue when mounting. The pungent smell subsided once the specimen was pressed. Seaweed presented an artistic and technical challenge (even for devotees such as Queen Victoria), for one had to work very carefully to avoid disrupting its complex structure. Added to that was the difficulty of wading into the water wearing heavy Victorian garb. The noted seaweed collector Margaret Gatty (1809-1873) recommended that “seaweeders” wear heavy men’s boots when wading: “Feel all the luxury of not having to be afraid of your boots.”

The collection also includes ferns gathered along the banks of the Shrewsbury River near to the family farm, as well as several specimens marked “Harlem,” reflecting the rural nature of that part of New York City in the mid-19th century.

Patience, Patience

One has to only glance at the Tredwells’ collection of pressed flora to realize the extraordinary precision, patience, and technical skill that was required to arrange the delicate specimens, especially the seaweed. Indeed, in a New York Times article from 1874, the reader is cautioned that seaweed pressing requires:

“… the greatest delicacy of touch and the most absolute attention. It would not be a bad idea to serve a preliminary apprenticeship at lace-making.”

Although they did not label their specimens, both Gertrude and Eliza created unique arrangements that are works of art. It must have taken hours to do such painstaking work; clearly both women loved exercising their artistic talents in this manner. Many of the flowers still retain their bright colors because they have had little exposure to light.

Mementos

It is uncertain if the trip to the White Mountains in July 1865 was the family’s first; they did make subsequent trips to the area, but none of the other pressings are marked as having been collected there. The latest specimen that bears Eliza’s name is dated August 24, 1876, and was collected from Seabright (another name for Rumson), when she was 79 years old! Eliza would die 6 years later, in 1882. We do not know how long Gertrude continued to enjoy the craft of flower pressing, or whether she derived joy from looking through the albums in later years. We like to think that they evoked sweet memories of happy days, and of her mother.

Sources:

- Farr, Judith. “Victorian Treasure: Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium.” February 19, 2014. Academy of American Poets. www.poets.org. (accessed 8/8/17).

- Giaimo, Cara. “The Forgotten Victorian Craze for Collecting Seaweed.” November 14, 2016. Atlas Obscura. www.atlasobscura.com. (accessed 8/8/17).

- “From Northampton. Beauties of the Scenery.” The New York Times, 01 Sep 1865, Pg. 1.

www.newspapers.com. (accessed 8/4/17). - Oatman-Stanford, Hunter. “When Housewives were Seduced by Seaweed.” Collector’s Weekly. November 7, 2013. www.collectorsweekly.com. (accessed 8/8/17).

- “Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains.” Museum of the White Mountains Online Exhibition. Plymouth State University. www.plymouth.edu. (accessed8/4/17).

- Richards, T. Addison. Appletons’ Companion Hand-Book of Travel. New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1862.

- “Seaweed Pressing.” The New York Times, 29 May, 1874, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. (accessed 8/4/17).

- Wallace, R. Stewart. “Turnpikes, Stage Coaches and the White Mountain Express: Transportation in the White Mountains.” wwwwhitemountainhistory.org/uploads/Turnpikes_enh.pdf. (accessed 8/4/17).

- Witemeyer, Karen. “Victorian Flower Pressing,” Petticoats and Pistols. April 30th, 2011. www.petticoatsandpistols.com. (accessed 8/8/17).

“The Destroying Angel:” New York’s 1832 Cholera Epidemic

by Ann Haddad

Disturbing News

In the harsh winter of 1831-32, Seabury Tredwell had cause for alarm. As he conducted his business at the seaport and in his warehouse on Pearl Street, he could not have avoided the terrifying news. It was spoken of at every turn, and reported daily in the newspapers: “King Cholera” was heading west! By mid-June, after cutting a path of death as it traveled west from India through Europe, cholera had crossed the Atlantic and reached Canada. If Seabury had kept a journal, most likely he would have written words similar to those of the former New York mayor and diarist Philip Hone, whose entry on June 15 reads:

“It [cholera] must come, and we are in a dreadful state to receive it.

The city is in a more filthy state than Quebec and Montreal.”

“Seabury Tredwell to Eliza Parker:” A New York City Wedding, June 13, 1820

by Ann Haddad

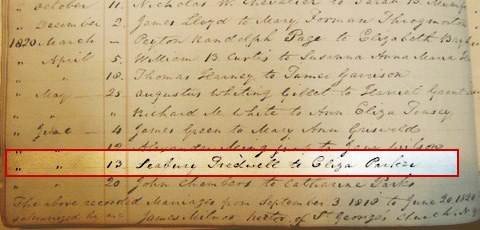

The entry in the wedding registry of St. George’s Episcopal Church on Chapel (now Beekman) Street, dated June 13, 1820, reads simply “Seabury Tredwell to Eliza Parker.” The tying of the knot between 40-year-old Seabury and 23-year-old Eliza, officiated by the rector, Reverend Dr. James Milnor (1773-1845), was the start of a 45-year union.

Wedding Registry, St. George’s Episcopal Church