Meet the Tredwells: The Ancestry of Seabury Tredwell

by Ann Haddad

With this post on the ancestry of Seabury Tredwell, we begin a new blog series: “Meet the Tredwells.”

A note about the variation of the spelling of Tredwell: Although early records seem to use “Tredwell” and “Treadwell” interchangeably, by the second generation in America “Tredwell” was used exclusively to denote this branch of the family. For the sake of clarity, this post will just use the spelling “Tredwell.”

In England

Seabury Tredwell’s ancestry can be traced as far back as 16th century England, to one Thomas Tredwell of Sibford Gower (before 1510-1545). His son, Alexander of Swalcliffe and Epwell (d.1603) was the father of Thomas (born c.1565). Thomas’ son Edward would leave England for the Colonies and begin the story of the Tredwell family in America.

Edward Tredwell, Emigrant

In 1635, Seabury Tredwell’s great-great-great-grandfather, Edward Tredwell (1607-1660), with his wife and two young children, emigrated from the small village of Swalcliffe, Oxfordshire, England, the seat of the prosperous Tredwell family. The family settled in the town of Ipswich, Massachusetts Bay Colony. In February 1637, the Massachusetts Bay Company granted Edward six acres of land “for planting.” Edward was one of over 20,000 emigrants who fled England for political, religious, and economic reasons, during what is known as the “Great Migration,” 1620-1640, and settled in New England.

And thus commences the story of the branch of the Tredwell family from which Seabury Tredwell (1780-1865) descended. The chronicles of this family, like the millions of others who came, and continue to come, to America, reflect the pursuit and attainment of the American Dream of peace, prosperity, and freedom.

In the ensuing years, Edward Tredwell, his wife, Sarah (nee Howes, 1609-1684), and their six children lived in the Colony of New Haven, and then Southold, on the North Fork of Long Island. By 1660, the year of his death, Edward Tredwell lived in Huntington, Long Island, then an agricultural area on the North Shore. No doubt he was a successful farmer, for upon his death his estate inventory was valued at 285 pounds sterling, a significant sum at that time.

John Tredwell, Esquire

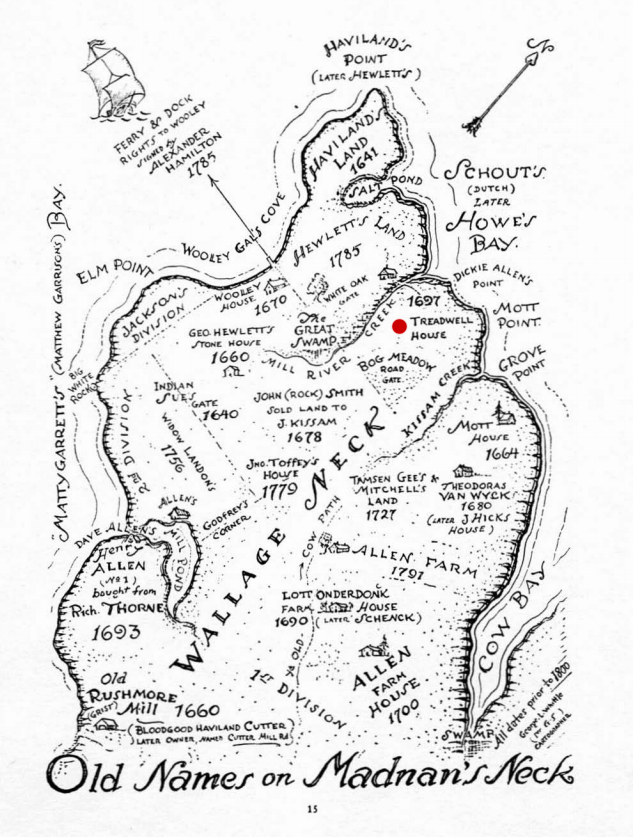

Seabury’s great-great-grandfather, John Tredwell (c.1644-before 1720), son of Edward and Sarah, moved from Huntington to Hempstead, Long Island, sometime around 1662. By 1685, John was farming 350 acres of land in Hempstead, an area known for its fertile ground, and for its abundance of wild game and fish. Throughout his adult life, John held many notable positions in the town, including assessor, county justice, auditor, constable, overseer, and surveyor. In court and civil records he was always referred to as “Gentleman” or “Esquire.” He married twice, first in 1666 or 1667 to Elizabeth Starr (who died before 1682), then to Hannah Smith (born before 1706-death unknown). In 1696, John purchased a 250-acre farm from John Kissam of Madnan’s Neck (now known as Great Neck), North Hempstead. It was the homestead of the Tredwell family for the next 100 years.

John Tredwell had two children with his first wife, Elizabeth. It is unknown if he had any children with his second wife, Hannah.

Thomas Tredwell, Captain of the Militia

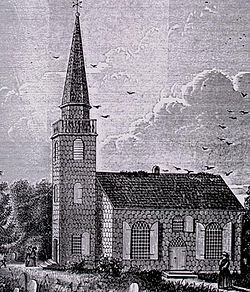

Seabury’s great-grandfather, Thomas Tredwell (before 1676-1722), son of John and his first wife, Elizabeth, continued farming the land at Madnan’s Neck; like his father, he also served as a vestryman and warden of St. George’s Church in Hempstead. In 1697, he was appointed by the Governor of the Province of New York to the office of Captain of a Company of Foot in Colonel Thomas Willet’s regiment. He held this position until his death, in 1722. His wife, Hannah Denton, whom he married sometime before 1698, died in 1748. Thomas and Hannah Tredwell had eight children. Clearly the Tredwell family had become wealthier over the years, for after his death Thomas Tredwell’s estate was valued at 825 pounds sterling.

Colonel Benjamin Tredwell

Seabury’s grandfather, Benjamin Tredwell (1702-1782), son of Thomas and Hannah, married his first wife, Phebe Platt, in 1727; she died in 1738 at the age of 28 years old. In 1739 or 1740, he married Sarah Allen (1717-1782). Benjamin, like his father and grandfather before him, was a farmer and a vestryman in St. George’s Church; he would later be instrumental in the building of a new church building in Hempstead.

He served as a Major in Colonel John Cornell’s regiment of the militia, and by 1750 was ranked as Colonel. According to Henry Onderdonk, Jr., in his Queens County in Olden Times (1865), Benjamin Tredwell was described as “a gentleman who ever supported an unblemished character and was remarkable for his hospitality, cheerfulness and affability.” Benjamin died just four months after the death of his second wife, Sarah.

Benjamin had four children with his first wife, Phebe, and five with his second wife, Sarah.

.

Doctor Benjamin Tredwell, Adventurer

Seabury’s father, Benjamin Tredwell, Jr., (1735-1830), son of Benjamin and his first wife, Phebe, lived a long and eventful life in Hempstead and later in East Williston, part of the town of Westbury. In 1756, as a 22-year-old physician and surgeon (likely trained by apprenticeship), he joined a privateering expedition against the French during the Seven Years War (1756-1763) on board the ship Hercules.

Marriage to a Mayflower Descendent

Six years after completing the voyage, Dr. Benjamin Tredwell married Elizabeth Seabury (1743-1818), daughter of Reverend Samuel Seabury (1706-1764), who was rector of St. George’s Church from 1742 to 1764; her half-brother, also named Reverend Samuel Seabury (1729-1796), became the first Episcopal Bishop of the United States (see “Uncle Sam(uel): Bishop, Loyalist … Broadway Star? from July, 2016). Elizabeth’s third great-grandfather was John Alden, who with his future wife, Priscilla Mullins, arrived in the New World aboard the Mayflower in 1620.

A Loyalist Brush with the British

During the Revolutionary War, in August 1776, British troops occupied Long Island and imposed martial law. Hempstead and its Churches of England were centers of military and Loyalist life. Dr. Tredwell, a vestryman of St. George’s, was an ardent Loyalist; in fact, he was one of the signers from Queens County of the Declaration of Loyalty to the King, dated October 21, 1776. At one point during the war, he quartered Hessian soldiers at his home; this show of loyalty to the King, however, did not prevent him and many other Loyalists from being denied favor and enduring mistreatment by the British. In 1776, while riding alone, he was robbed of his valuable horse by Lieutenant-Colonel Birch, Commander of the 17th Light Dragoons. The eminent physician was sent home carrying his saddle. When he protested the injustice of the theft, Dr. Tredwell was labeled a “rebel” and threatened with arrest.

A Rabble of Rebels

Dr. Benjamin Tredwell’s wife, Elizabeth, also beloved by the community and known for her hospitality, was involved in an what must have been a frightening incident during the Revolution: on August 2, 1780, while returning from New York City in a chaise, she was robbed of her horse and money by a group of militant patriots. Her eight-year-old son, Adam, who in his adulthood became a successful fur merchant in New York City, was with her at the time. It is extremely fortunate that Mrs. Tredwell was unharmed during this incident, for one month later, on September 25, she gave birth to the eighth of her nine children, Seabury Tredwell.

Slavery and Servitude

The presence of the institution of slavery on Long Island during the 17th and 18th century is clearly documented in the historical record. Slave records exist in Long Island as early as 1683. Four generations of Seabury’s ancestors owned slaves who worked the Tredwell farms. According to the 1800 Federal census, Benjamin Tredwell, Seabury’s father, owned six slaves. Slavery was finally abolished in New York in 1827.

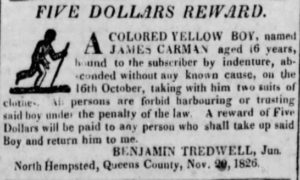

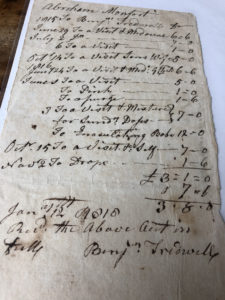

Dr. Benjamin Tredwell also hired indentured servants to work for him; indentures were legal contracts that bound a person to work for another for a specified period of years. In 1826, Benjamin Tredwell paid for an advertisement in the Long-Island Star, in which he offered $5 for the return of one James Carman, a runaway. Servitude remained legal in New York State until its abolition in 1917.

Slaves Freed

With the creation of the New York Manumission Society in 1785, abolitionist New Yorkers set about promoting the gradual manumission (release from slavery) of slaves. New York passed its first gradual emancipation law in 1799. This law provided that all children born into slavery after July 4, 1799 in the state would be freed when they turned 25 (for women) or 28 (for men). This meant that slaveholders would be able to retain their slaves during their most productive years. Slavery was finally abolished in New York in 1827.

Dr. Benjamin Tredwell legally freed three of his slaves in 1808, 1810, and 1819, by signing manumission registration certificates. The three slaves were adults at the time they received their freedom. Dr. Tredwell, along with the Overseers of the Poor of Queens County, who issued the certificates, had to guarantee that each freed person was “of sufficient abilities to provide for himself.” He retained at least one slave, however; in his Last Will and Testament, dated September 21, 1829, he bequeathed his “female slave, Cloe,” to his son Benjamin. Although this was illegal, it most likely was by mutual consent. If Cloe was incapable of supporting herself (perhaps she was elderly or disabled), this could be viewed as at act of charity. If she did not live with Benjamin’s son, her only other option, most likely, was the almshouse.

“Esteem and Confidence”

Family lore has it that on the birth of each of his children, Dr. Tredwell planted an evergreen tree in front of his house. By 1784, with the birth of his last child, George, Benjamin would have planted nine evergreen trees. All of Benjamin and Elizabeth’s children lived to adulthood.

Upon his death at the age of 95, Dr. Benjamin Tredwell’s obituary in the Long Island Telegraph and General Advertiser (June 24, 1830), stated:

“Such is said to have been the esteem and confidence of the community in this aged Physician, that to the last, he retained a large portion of the practice in the neighborhood where he resided.”

The next blog post in the series “Meet the Tredwells” will explore the fascinating story of Eliza Earle Parker Tredwell’s ancestors.

.

.

.

Sources:

- Ancestry.com. 1790 and 1800 United States Federal Census. [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Ancestry.com. New York County, New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1658-1880 (NYSA) [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA; ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Ancestry.com. New York, Wills and Probate records, 1659-1999 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Accessed 2/11/19.

- Cutter, William Richard, ed. American Biography: A New Cyclopedia, Vol XL. New York: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1930, pgs. 177-178.

- Hawk, Alan J. “ArtiFacts: Benjamin Tredwell Jr.’s Amputation Knives.” Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research (2018) 476: pgs. 1715-1716. www.researchgate.net. Accessed 2/8/19.

- Hoff, Henry B. Genealogies of Long Island Families, Vol. II. From The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. Volume II. Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc, 1987.

- Jones, Thomas. History of New York During the Revolutionary War, Volume I. New York: The New York Historical Society, 1879, p. 114-116. www.internetarchive.org. Retrieved 3/12/16.

- Long-Island Star (Brooklyn, New York) 23 November, 1826, Thursday, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Luke, Dr. Myron H. Vignettes of Hempstead Town 1643-1800. Hempstead, New York: Long Island Studies Institute, 1993.

- Mather, Frederic Gregory. The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut. Albany, N.Y.: J.B. Lyon Co., 1913, p. 607-608. www.internetarchive.org. Retrieved 5/5/16.

- Moore, William H. History of St. George’s Church, Hempstead, Long Island, N.Y. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1881. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/8/19.

- Onderdonk, Jr., Henry. Documents and Letters Intended to Illustrate the Revolutionary Incidents of Queens County. New York: Levitt, Trow and Company, 1846., p. 117-128, p. 172-173, p. 244-249. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 3/11/16.

- Robbins, William A. “Descendants of Edward Tre[a]dwell Through His Son John.” The New York Genealogical & Biographical Record. April, 1912 (Volume 43, No. 2), p. 127; Ibid., July, 1912, (Volume 43, No. 3), p. 221; Ibid., Oct, 1912 (Volume 43, No. 4). www.archive.org. Accessed 2/8/19.

- Smith, Dean Crawford. The Ancestry of Eva Belle Kempton, 1878-1908, Part II: The Ancestry of Amanda Spiller 1823-1873. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2008.

- St. George’s Episcopal Church Archives. New York, NY. Record of St. George’s Church/Baptisms 1809-1830/Marriages 1816-1837.

- Treadwell, Thomas Alanson. “Tredwells in Search of Tredwells: Adventures in Ancestry.” New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, 104, No. 4 (1973): 195-204.

- Tredwell, Thomas Allison., “Tredwells in Search of Tredwells” in New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, 104 (1973): 195-204.

- Wilson, James Grant, ed. The Memorial History of the City of New York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892 Volume II. New York: New-York History Company, 1892. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/11/19.

What you are doing is invaluable! Knowing this information about the Tredwell family and having it readily available for researchers or anyone interested in the Merchant’s House is simply marvelous! It enhances the Merchant’s House as a historic document. It’s not just an old house—it’s a historic home where real people lived and here they are and here’s how they got here. Congratulations! I look forward to the rest of this series.

I never even imagined we would have this type of insight into the Tredwell family, what a true marvel you are!

Thank you so much for writing this history. It is a real insight into the lives of a family and how they lived. I had heard we were related to John Alden but this cleared it up for me. I haven’t made it to the Merchant’s House yet but now it is certainly on my ‘bucket list’ I just wish the family had held on to a few square blocks of the upper east side to pass down to future generations (like me).

Hi I am Gail Treadwell from the UK a descendant of Thomas and Edward Treadwell from Oxfordshire

Hello Gail! Thank you for reading my blog post and for your comment. I imagine there are many descendants of the early Treadwells. I do hope you have the opportunity to visit the MHM one day!

Hi Ann

I am a descendant of Caroline Treadwell born in New Jersey between 1815 and 1820. Unfortunately women had no bios at that time. She was my 2nd gt grandmother. Your information is wonderful.Thank you

This was a gold mine of information to add to my family tree. The Woolleys were neighbors, friends and spouses of the Tredwells in Great Neck. The intro indicates this page was the first in a blog series called, “Meet the Tredwells,” but I can’t find where subsequent blogs may have been posted. Can you please help me find them, assuming they exist? Thanks very much!

Hi Bill, I’m glad this information was helpful to you. To see all my blog posts, go to the Merchant’s House Museum website, click on “Learn,” then from the drop-down menu choose Blog (it’s at the very bottom).