Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part 4 – The End of an Era

by Ann Haddad

..

On February 4, 1835, a notice appeared in the Shipping and Commercial List and New-York Price Current that the hardware firm of Tredwell, Kissam, and Company, which had flourished for over 20 years on Pearl Street, was “dissolved by mutual consent.”

That same year, Seabury Tredwell moved his family from their home on Dey Street, in lower Manhattan not far from the seaport, to a Late Federal/Greek Revival row house on Fourth Street, in the neighborhood then known as the elite “Bond Street area.” He was 55 years old, and not about to retire from the world. For 30 years until his death he maintained an active life, keeping pace with the enormous economic changes taking place in New York City and making shrewd investments in real estate, railroads, and natural gas. (For more information about Seabury Tredwell’s hardware business and investments, see Seabury Tredwell: The Merchant Years and Seabury Tredwell: Man of Opportunity). His years of hard work led to outstanding success and enormous wealth. Now we turn our attention to his final illness and death in March 1865.

..

..

..

Seabury’s Final Illness

For some years leading up to his death, Seabury’s attending physician was Dr. George E. Belcher (1818-1890), a practitioner of homeopathy, an alternative medical practice. Dr. Belcher had converted to homeopathy from conventional medical treatments in 1844. (For more information about homeopathy and the Tredwell family’s physicians, see my blog post of October 2016: The Doctor in the House is a Homeopath!). Seabury’s death certificate, signed by Dr. Belcher, states he died from acute kidney failure caused by Bright’s Disease, now known as acute or chronic nephritis (inflammation of the kidneys). The disease is characterized by a wide range of symptoms, including swelling, coma, stroke, convulsions, and blindness.

Seabury’s homeopathic treatment plan likely included the administration of herb and plant remedies, such as arsenicum, belladonna, burdock root, and juniper berry; dietary restrictions (no red meat, cheese, or alcohol); warm compresses and massage of the lower back for pain; and inhalation of lavender oil to reduce anxiety.

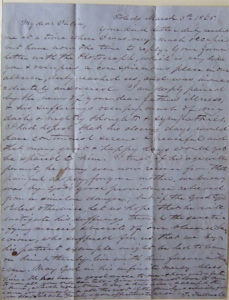

Although Dr. Belcher listed Bright’s Disease as the cause of death on Seabury’s death certificate, we do not know how long he suffered with the disease. According to a story related by his granddaughter Elizabeth Tredwell Stebbins (1885-1973), Seabury caught a cold after returning from his home in Rumson, New Jersey, by boat one winter’s day in 1865, which led to his death on March 7. On March 3, his nephew Timothy Tredwell, who lived in Toledo, Ohio, penned a letter to Seabury’s daughter Julia, after learning of his condition:

“I am deeply pained by the news of your dear father’s illness & his sufferings occupy much of my daily & nightly thoughts & sympathies… May god in his infinite mercy bless him. He has been a good uncle to me & how good a father to you all, you only can tell.”

The Civil War Draws to a Close

In early 1865, as Seabury’s life was coming to an end, the nation witnessed the collapse and death of the Confederacy. The Union Army, thanks to the brilliant military strategies of Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman, left the Confederate Army in tatters. Passage of the 13th Amendment at the end of January 1865 abolished slavery and on March 4, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as President for a second term in Washington, D.C. One month later, on April 9, the Civil War ended when General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

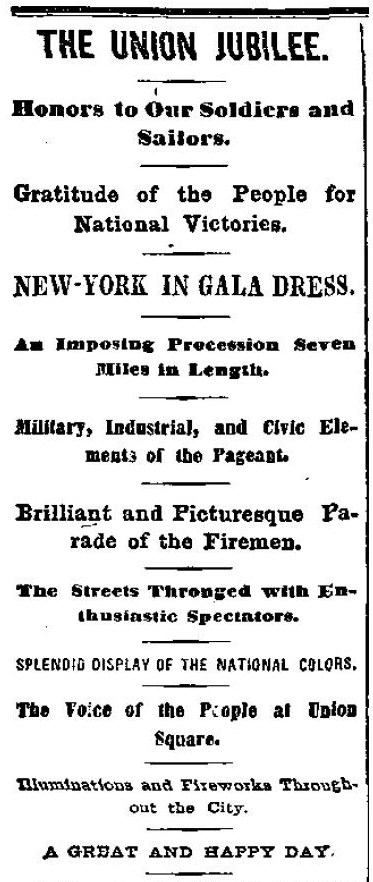

The Union Jubilee

On March 6, as Seabury lay on his deathbed, surrounded by his family, New York City joyously celebrated the anticipated end of the Civil War with a “Union Jubilee.” Over one million spectators lined the streets to see the grand parade, which included military troops; volunteer firemen; members of clubs, businesses, and community organizations; and even a menagerie of, among other animals, elephants and camels. John Ward, Jr., who was a National Guardsman and who lived near the Tredwells, on Thompson and Bleecker Streets, marched in the parade with his Company; the excitement of the event is palpable in his diary entry:

“Beautiful, perfect day. I put on my uniform and medal after breakfast & rigged the flag out of Mother’s window. …We formed in Washington Square….Tremendous crowd. Largest ever known. We wheeled well into Broadway, marched down to the Museum, up Park Row, etc., and Bowery to Union Square (where we saw the procession still passing down Broadway) up 4th Avenue, to 23rd Street, up Madison Ave. to 29th St…up to 33rd St. over to 8th Ave., down to Washington Square where we were dismissed. Flags & decorations were fine. …Dined. Then went to Union Square to see the fireworks. Great crowd. Splendid pieces. Change of rebel to loyal flag. “Sumter” “Bombardment of Fort Fisher,” “Monitor & Merrimack” etc. Rockets & balloons. Homes and clubs illuminated. Mother had gas all lighted.”

As the Tredwell family maintained their vigil at Seabury’s deathbed that day, they surely heard the commotion of the celebration, the pealing church bells, and the gun salute fired in Union Square to signal the start of the parade. It is hard to imagine them sharing in the immense relief and happiness of the citizens of New York City. And the no doubt unadorned Tredwell home on Fourth Street must have stood out sharply among its neighboring dwellings, for The New York Daily Herald reported on March 7:

“Looking at the houses, you beheld one, grand continuous exhibition of flags from windows, poles, awnings, and every point whereon to hang this badge of loyalty and nationality. All of the hotels and public buildings were covered with the Stars and Stripes, and many houses displayed mottoes and inscriptions of an appropriate character.”

|

Death of the Patriarch

The day after the “Union Jubilee,” on March 7, Seabury died at the age of 84. His wife, Eliza, their eight children, and five grandchildren, survived him. After being waked in the front parlor for three days, on March 11 (a “beautiful, bright cold day,” according to John Ward, Jr.), Seabury’s funeral took place in the double parlor of his home, and he was interred in the New York City Marble Cemetery on East Second Street. On December 28, he was moved to his final resting place in the family plot in Christ Church Cemetery in Manhasset, Long Island.

A Family, and a Nation, Mourn

Eliza Tredwell and her family were approximately one month into their mourning period for Seabury when the American Civil War ended on April 9, 1865. Five days later, on April 14, President Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, and the glory of the Union victory was instantly forgotten, as the City plunged into mourning. Philip Hamilton Hill (1839-1915), a 27-year-old York City dry-goods clerk, noted the tragedy in his diary on April 15:

“Was horrified on waking this morning, to hear that President Lincoln was assassinated last night at Ford’s Theatre, Washington, by a man supposed to be J. Wilkes Booth the actor, and that an attempt had been made, upon the life of Sec’y Seward. Business was at a standstill all day, many of the Stores being closed, and most all draped in mourning, and a feeling of intense excitement existed throughout the City.”

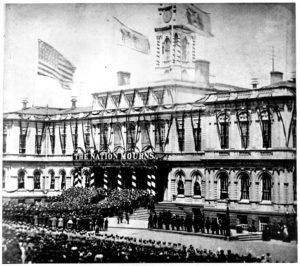

On Tuesday, April 25, Hill recorded in his diary how he joined the crowd (over 150,000 mourners) which lined up outside City Hall, from which hung a banner reading “THE NATION MOURNS,” to view the late President’s body, and the somber mood as Lincoln’s funeral cortege passed through New York City:

“By dint of hard work, and a good deal of tight squeezing, I managed to get through. I wouldn’t go through the same crowd again for ten dollars…The remains lay at the door of the Governor’s room, surrounded by a guard of honor…He looked the same as in life, with the exception of his skin, which was of a much darker hue….At 1 P.M. all the stores were closed, and the funeral procession commenced to move up Broadway towards the train on the Hudson River road which was to convey the remains West. Had our room full of company to view the procession.”

One wonders if any of the Tredwell family joined Hill at City Hall to view the President’s remains. They most likely joined the half a million New Yorkers who viewed the funeral procession, as it made its way up Broadway past Fourth Street. Even in their mourning attire, they would not have stood out in the crowds, for on that day many women donned widow’s weeds, and the men wore black crepe armbands, as a sign of their grief over President Lincoln’s death.

A Long Mourning Period

Mourning, the personal expression of loss and grief, was considered women’s work in the 19th century. Men, as the breadwinners who had to return to the workforce, were not expected to remain at home and follow the societal restrictions required by mourning etiquette. They donned a black hatband or armband and resumed their regular life. It fell to the women of the house to conform to social norms, by donning black mourning attire, sharply curtailing their socialization, and following the other precise rules of mourning frequently found in popular household manuals. The ability to follow elaborate mourning rituals was also a subtle indication of the wealth, respectability, and social status of the family; mourning attire and its accoutrements were expensive.

For Eliza Tredwell, mourning and all its associated traditions became a daily part of her life, perhaps for the remainder of her life. Typically, a widow in “full” or “deep” mourning adhered to a strict dress code of dull black for a year and one day, then proceeded, in the ensuing nine months to one year, to “half-mourning,” in which some colors, such as gray, white, mauve, and lavender, were permitted.

For much more information about mid-19th century mourning customs, please visit our exhibition “Death, Mourning, and the Hereafter in Mid-19th Century New York,” on view from September 26 to November 4. As part of the exhibition, visitors may meet Mrs. Tredwell in the front parlor and offer their condolences every Saturday afternoon in October from 1:30-3:30 p.m.

The End of an Era

An obituary in the New York Post on March 11, 1865, noted Seabury’s death:

“Among the deaths noticed in our column today is that of one of our oldest and most respected merchants, Seabury Tredwell. He was a gentleman of the old school, dignified and accomplished in his manners and high-minded and honorable in all his transactions…“He now goes out from us, one of the last of his generation, honored, respected and beloved by all.”

Sources:

- Hill, Philip Hamilton. Diaries, 1855-1865. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Knapp, Mary L. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- New York Daily Herald. March 7, 1865, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/17/19.

- New York Evening Post. March 11, 1865. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/9/19.

- New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1759-1949. www.familysearch.org.

- Merchant’s House Museum Archives. Tredwell, Timothy. Manuscript Letter, March 3, 1865. MHM 2002.4601.32.

- Shipping and Commercial List and New-York Price Current. February 4, 1835, p. 3. America’s Historical Newspapers, via ProQuest. Accessed 6/29/17.

- Spann, Edward K. Gotham at War: New York City, 1860-1865. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 2002.

- Strausbaugh, John. City of Sedition: The History of New York City During the Civil War. New York: Twelve Hachette Book Group, 2016.

- Ward, John. Diaries, 1847-1888. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.