Ladies of Refinement: The Women Who Educated the Tredwell Daughters

by Ann Haddad

Six Tredwell Daughters to Educate!

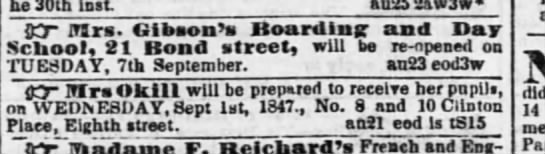

As the daughters of a prosperous merchant, the six Tredwell girls were granted all the privileges of the elite class in which they were raised, including a private school education. From among the many girl’s schools in New York City, Seabury and Eliza chose two of the best for their daughters – Mrs. Okill’s and Mrs. Gibson’s. [For a discussion of private school education for boys, click here to read “Samuel Tredwell’s School Days,” September, 2017.]

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Mary Jay Okill owed a debt of gratitude to the Tredwell family. Mrs. Okill (1785-1859), was the headmistress of one of the most highly regarded female academies in New York City in the Antebellum era. Seabury and Eliza Tredwell, by entrusting her with the education of all six of their daughters over a period of at least 20 years, demonstrated support for Mrs. Okill’s system of education, at a time when the wealthy and elite families of the City could choose from among many similar private institutions. The decision by the Tredwells to send their daughters to Mrs. Okill’s likely influenced other wealthy families in their circle.

The Finishing Touch Plus Morality

In the first half of the 19th century, the aim of elite female education was to provide young ladies with the social graces and manners befitting their place in society, and to instill a basic knowledge of literature, classics, arithmetic, and geography. Several schools also included instruction in the religious and moral principles that would lead to the development of virtuous, charitable, and benevolent character. This approach, which Mary Okill outlined in detail in her first advertisement for her new academy in the Christian Journal, and Literary Register (1823), certainly appealed to parents such as Seabury and Eliza Tredwell, for it would essentially “finish” their daughters by preparing them for the most important roles within their sphere: those of wife and mother. As the advertisement states:

“… while every attention will be paid to the ordinary and ornamental branches of a finished female education, the department of religious instruction will receive particular care. Mrs. Okill … will devote her time to the superintendence of her school, and to the religious principles, morals, and manners of those young ladies who may be confided to her care.”

So Many Choices!

The single-gender “academy,” copied in style and substance from the British finishing school, was extremely popular among the wealthy of New York City in the early-mid 19th century. Such schools, which occupied rented houses run by a head teacher, typically offered opportunities for both day and boarding school students; the staff, who lived at the establishment, included other teachers, cooks, and domestic servants. Teacher training and curriculum was not standardized. With time and the increasingly progressive nature of female education, the homelike atmosphere gradually transitioned to larger, more structured female academies (also called seminaries), with formally trained teachers and rigorous curriculums. [For a detailed description of what the Tredwell girls would have experienced while students at Mrs. Okill’s, see Mary Knapp’s An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65 (2012)].

Mrs. Okill’s Tops the List

Competition for students must have been fierce among the women who ran the schools. Every year, beginning in late August and continuing through mid-September, advertisements for the schools, complete with names of notable individuals who were willing to provide endorsements, appeared in the daily newspapers. In New York As It Is (1833-1837), Mrs. Okill’s name is at the top of a list of 20 “Principal Female Seminaries” spread throughout the city. Ten years later, that number had grown significantly. In addition to Mrs. Okill’s, some of the other renowned female schools during this period, as mentioned by Catherine Elizabeth Havens (1839-1939), in her Diary of a Little Girl in Old New York (1919), were:

“Madame Chegaray’s, Madame Canda on Lafayette Place [both french schools], Mrs. Gibson on the east side of Union Square [more about her later], Miss Green’s on Fifth Avenue, just above Washington Square, and Spingler Institute on the west side of Union Square, just below Fifteenth Street.”

Influential Connections

When one considers that Mrs. Okill included the name of Reverend Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk (1791-1861) as a reference in her advertisements, it is understandable that Seabury Tredwell supported the school. Onderdonk was a relative of Seabury’s, and, as Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, a highly respected clergyman (until he wasn’t: stay tuned for a future post that will discuss his 1845 downfall). Other renowned citizens of New York, including Bishop Hobart, James Bleecker, and Peter A. Jay, also endorsed her school, which served to guarantee her cachet among the upper class.

Mrs. Okill Illegitimate … and a Divorcee?

Several circumstances of Mrs. Okill’s life, however, turn her pedigree on its head, notably her illegitimate birth and her divorce.

Mary Jay Okill was the daughter of Sir James Jay (1732-1815), oldest brother of John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Sir James, known primarily as the inventor of an invisible ink used by George Washington and his spies during the American Revolution, was also a physician and member of the New York State Senate; he was knighted by King George III for his fundraising efforts on behalf of Kings’ College.

According to an article in the Newsletter of the Bergen County Historical Society (2015-16), Sir James Jay never married Mary Jay’s mother, Anne Erwin (1750-1840), although they lived together in Springfield, New Jersey. A staunch advocate of a woman’s right to education, Miss Erwin refused to “honor and obey” Sir James, and therefore no marriage took place.

Mary Jay married John Okill, a merchant, on August 13, 1807, at Saint John’s Church on Varick Street. City Directories indicate that from 1807 through 1814, the couple lived with her father at various addresses on Greenwich Street and White Street. After Sir James’ death in 1815, neither Mary nor John Okill appear in the directories until 1819, when John Okill is listed as a broker on Wall Street. This entry remains unchanged until 1823, when he disappears entirely from the directories. The date and place of his death could not be determined.

In his will, probated in 1815, Sir James Jay stipulated that his daughter Mary’s inheritance, which included nearly 1,000 acres of land in what is now Closter, New Jersey, be put in trust “free of any control of her present husband, John O’Kill [sic].” According to the aforementioned article, Mary Okill divorced her husband in order to claim her inheritance. To earn a living, and perhaps influenced by her mother’s feminist beliefs, she opened a school for young ladies. Mary Okill is first listed in the 1823-4 City Directory as the proprietor of a “boarding school,” located at 43 Barclay Street. She remained at this location until 1838, when she moved to 8-10 Clinton Place (now 8th Street). She maintained her school until her death in 1859. Her establishment was always known as Mrs. Okill’s Academy.

What a Woman!

It is remarkable that, despite the social stigma associated with illegitimacy and divorce during the 19th century, Mary Okill was able to achieve such renown, especially among the privileged class, who valued family pedigree above all else. One wonders what shielded her from disgrace? Did her wealthy patrons know of her past, and decide to simply look the other way, due to the reputation of her uncle, John Jay? Or did she somehow manage to keep her background and divorce hidden from public scrutiny? In whatever manner she managed to maintain her reputation, her school was continuously celebrated as being run by “a lady of distinction,” and was undoubtedly a huge financial success. In an article in the New York Daily Herald (January 11, 1845), Mrs. Mary Okill is one of only a handful of women included in a list of the “wealthiest citizens” of New York City, with a net worth of $150,000. She joined such wealthy men as Adam Tredwell, Seabury’s brother, whose net worth was listed at $200,000.

The Tredwell family had an indirect connection to John Jay, which may have been a factor in their loyalty to Mary Okill. Reverend Samuel Nichols, Elizabeth Tredwell’s father-in-law, who married Elizabeth and Effingham in 1845, pronounced the eulogy at the Chief Justice’s funeral in 1829. Additionally, one of Effingham’s brothers, John Jay Nichols, was his namesake.

Co-Ed for the Children

Although it was known primarily as a female school, Mrs. Okill’s Academy also welcomed very young boys as students. Julia Lawrence Hasbrouck (1809-1873), who lived on Greenwich Street, enrolled her six-year-old son Louis and her five-year-old daughter Julia in Mrs. Okill’s Academy in 1843. She wrote her positive impressions of the school in her diary on November 30, 1843:

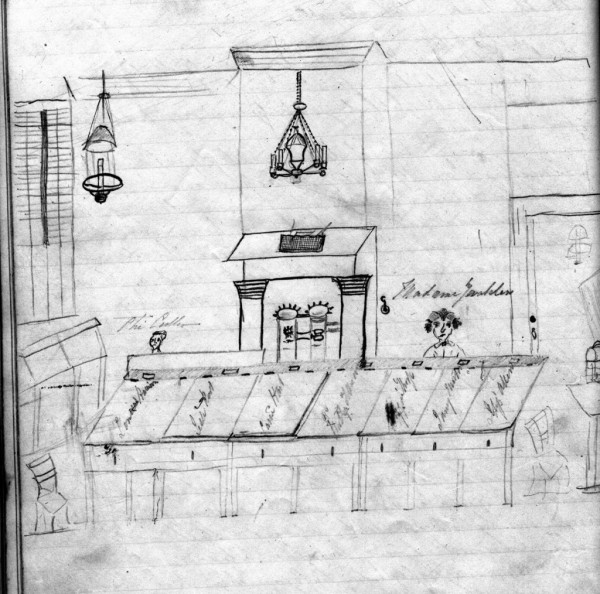

“The room was neat, comfortable, and well arranged. The little boys all looking happy, and merry. We went from there, to the little girls room, where I was equally pleased. The little creatures are not pinned down to their seats like prisoners, pale, and wearied; but were skipping around, combining study and amusement, the only safe method of instructing children.”

Although young Julia Hasbrouck attended Mrs. Okill’s at least through 1850, her brother Louis eventually joined another brother at an all-boys school. It is possible, then, that the Tredwell girls (and perhaps boys) attended Mrs. Okill’s from a much earlier age than was previously assumed.

Notable Students

In addition to the Tredwells, Mrs. Okill’s school attracted other families that made up the glitterati of New York society.

One of Mrs. Okill’s students was Eliza Hamilton Schuyler (1811-1863), the granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton. In 1825, when she was a 14-year-old student, Eliza was given a “prize book” from Mrs. Okill. In the Hamilton-Schuyler Family Papers at the University of Michigan, there are references to “Miss Okill’s ‘Testimonials’ for Eliza on that dainty embossed note paper …” and “While Eliza Hamilton was at Mrs. Okill’s School winning her encomiums …”

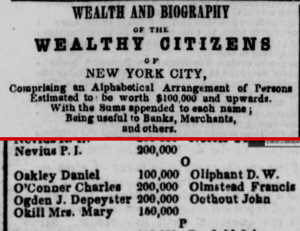

Another was Isabella Stewart (1840-1924), the daughter of a wealthy merchant, who would later marry John Lowell Gardner and become a famous art collector and philanthropist. From ages 5 to 15, while living with her family at 10 University Place, Isabella attended Mrs. Okill’s Academy. In 1855 she was awarded a Certificate of Excellence by Mrs. Okill, in return for a commitment to “remain till the close of school to receive it.” One year later, Isabella embarked on the Grand Tour of Europe with her parents and was enrolled in a French school to finish her education.

After Mary Okill’s death in 1859, the school closed, but her widowed daughter, Jane Swift, who had been a teacher at the school, continued to reside there. By May 1860, when the family moved to West Point, New York, the “very valuable property” on Clinton Place was up for sale. Like Mrs. Okill herself, the buildings were considered to be “of a superior character.”

Gertrude Tredwell, the Transfer Student

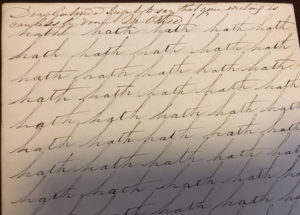

Among the copybooks belonging to the Tredwell girls in the Merchant’s House Museum archives, several belonged to Gertrude Tredwell. One, dated from December 16,1853, through February 13, 1854, (when Gertrude was 13 years old), indicates that Gertrude attended Mrs. Okill’s School, for at the end of a composition, a withering comment appears, written by the headmistress herself:

“Dear Gertrude, I regret to say that your writing is carelessly done. M. Okill”

Other copybooks of Gertrude’s, which date to 1858, do not contain any teacher’s notes. The Museum’s copy of Seabury Tredwell’s ledger book includes entries for payment of bills for “Gertrude’s tuition at Mrs. Gibson’s,” dating from 1855 and 1858 (tuition at the private academies averaged approximately $70 per year). We don’t know the reason for Gertrude’s departure from Mrs. Okill’s School. Whatever the reason for the transfer, Gertrude finished her education at the age of 18, under the tutelage of Mrs. Gibson.

Mrs. Gibson

In 1832, nearly ten years after Mrs. Okill opened her female academy, Mrs. Agnes Mason Gibson (1787-1872), from Edinburgh, Scotland, established her own school, assisted by three of her daughters. Originally located on Broome Street and operating as a day school, it was advertised on April 10, 1832, in the Evening Post:

“The Misses Gibson, having been educated under the first masters, are prepared to give instruction in all the branches of a useful and ornamental female education. Pupils will be received for French, Italian, Music, or Drawing, who may not wish to enter for other branches. Instructions upon the pianoforte and guitar will also be given in private homes. [Guitar instruction was not unusual. Christian Frederick Martin, the famous guitar maker who established his shop in New York City in 1833, sold several guitars to Mrs. Okill]. A class for conversation and composition in French will be opened on Saturdays, for young ladies who have made proficiency in the language.”

A Resounding Success

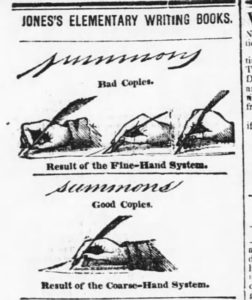

Two months later, Mrs. Gibson “expanded her plan” to include boarding students. Within a few years, her school achieved a remarkable degree of popularity; Mrs. Gibson became an influential educator in New York City. Manufacturers of school supplies sought her out for endorsements. In September 1838, an advertisement in the Evening Post featured Mrs. Gibson’s endorsement of Jones’s Elementary Writing Books. Mrs. Gibson stressed the importance of having children instructed in “large hand exercises:”

“I attribute the defects in the hand writing of young ladies to injudicious teaching in giving fine-hand exercises to write, before any foundation or command of the pen is acquired in large characters.”

“An Excellent Seminary”

As the school expanded it relocated several times, from Broome Street to Broadway to 21 Bond Street (just two blocks from the Merchant’s House), where in 1845, Mrs. Gibson gave an exhibition of her students’ work, which was lauded in the New-York Tribune. The school was referred to as “an excellent seminary – one of the best in the city for the instruction of young ladies.” The article goes on to say:

“We were particularly struck with the taste and judgment displayed in the elocutionary exercises. The French dialogues were given in a sprightly and graceful manner, and the vocal music was charming. We traced throughout the evening the workings of an intelligent, kindly, and well sustained course of instruction.”

The New York Post also covered Mrs. Gibson’s May Day Festival in May 1849:

“Of note were the performances of charades, in which the ingenuity and invention of the youthful scholars were exhibited. Many of the former pupils were present. It is charming thus to see wisdom’s ways made ways of pleasantness.”

The Dear Scottish Daughters

One of Mrs. Gibson’s students was Julia Cullen Bryant (1831-1907), daughter of poet and New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), who attended the school in 1844 at age 13. The family must have formed a strong attachment to Mrs. Gibson and her daughters, for William Bryant maintained a correspondence with his daughter’s teachers, Christianna Gibson in particular, until his death.

The Final Move

In 1851, Mrs. Gibson moved again, from 21 Bond Street to larger quarters at 38 Union Place, to accommodate her growing enrollment. Gertrude attended the school at this location, which was a short walk from her home on Fourth Street. The school operated at this location at least until 1861; eventually, Mrs. Gibson returned to Scotland with her daughters, where she died in 1872.

“An Annoyance and a Pleasure”

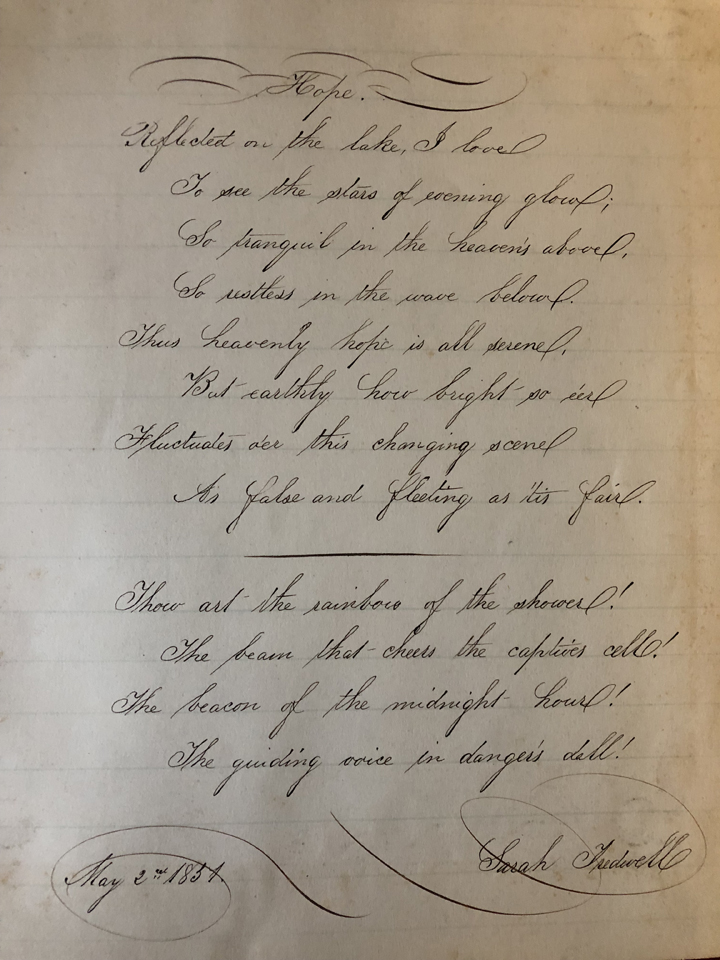

Despite the number of filled copybooks belonging to the Tredwell girls, all but one lacked any clues about the young women’s sentiments toward their schools. Only 18-year-old Sarah was brave enough to venture an opinion about her school years and the education she received. In a composition entitled “To a Dear Friend,” dated May 18, 1853, she expressed her ambivalence about her experiences and the end of her school days:

“Some say our school days are the most happy. I believe it to be true though there are certainly many things pertaining to school which are of a very perplexing nature. I will leave school the first of July, when I am to leave forever that place which I have frequented so many years and which has been to me both an annoyance and a pleasure. To those to whom I have grown and with whom I have shared the troubles of a school day life and to whom I must ever feel attached I must bid adieu but I hope not forever.”

Sources:

- Brown, Henry Collins. Valentine’s Manuel of Old New York, new series, no. 2. New York: Valentine Co., 1917.

- Bryant, William Cullen and Thomas G. Voss. The Letters of William Cullen Bryant: Volume IV, 1858-1864. New York: Fordham University Press, 1993.

- Christian Journal, and Literary Register, Volume 7-8, May, 1823. https://books.google.com. Accessed 9/9/18.

- Colony Club. Catalogue Exhibition “Old New York” Relics Documents and Souvenirs. New York: Colony Club, 1917.

- Evening Post. 25 August, 1824, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/5/18.

- Evening Post. 10 April, 1832, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 13 June, 1832, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 10 September, 1833, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- Evening Post. 22 August, 1834, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 13 January 1838, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- Evening Post. 1 September, 1838, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 30 August, 1847, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Evening Post. 3 May, 1849, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Evening Post. 14 April, 1851, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Gura, Peter F. C.F. Martin & His Guitars, 1796-1873. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Hamilton-Schuyler Family Papers 1820-1924, William L. Clements Library Manuscript Division, University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu. Email 9/6/18.

-

Hayley, Ann, Robert Campbell et al. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: Daring by Design. New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2014.

- Knapp, Mary L. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- Leslie’s History of the Greater New York. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York register, and city directory. New York: David Longworth, [multiple years]. Reference, New York Historical Society.

- Madigan, Jennifer C. “The Education of Girls and Women in the United States: A Historical Perspective.” Advances in Gender and Education, 1 (2009), 11-13. www.mcrcad.org. Accessed 9/2/18.

- Manhattan, New York City, New York Directory: 1829-1830;1839-1840. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- Merchants House Museum Archives. Seabury Tredwell’s Ledger Book [copy], 1855-1865.

- Merchant’s House Museum Archives. Composition Book of Sarah Tredwell, May 18, 1853. 2002.4601.89.

- Merchants House Museum Archives. Penmanship book of Gertrude Tredwell, Dec. 16th, 1853 – Feb. 13th, 1854. 2002.4602.29.

- New York County, New York, Wills and Probates, 1658-1880. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- New York Evening Post. 22 Dec 1859. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- New York Evening Post. 27 June 1839. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- New York Daily Herald. 11 January 1845, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- New York Daily Herald. 26 February, 1856, p. 5. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- New York Herald. 9 August, 1922, p. 11. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/22/18.

- New York Times. 20 September, 1859, p. 6. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/5/18.

- New York Times. 15 May, 1860, p. 6. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- New-York Tribune. 30 December, 1845, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Stessin, Susan. The Diaries of Julia Lawrence Hasbrouck. www.frommypenandpower.wordpress.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- Williams, Edwin, ed. New York As It Is, [1833-1837]. New York: J. Disturnell, 1833-1837.

- Wilson, James Grant, ed. The Memorial History of the City of New-York, Vol. III. New York: New-York History Company, 1893. https://books.google.com. Accessed 9/5/18.

- Wright, Kevin. “Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Tenafly.” In Bergen’s Attic: Newsletter of the Bergen County Historical Society. Fall/Winter, 2015-2016, p. 7-14. www.bergencountyhistory.org. Accessed 9/11/18.

The Wedding “Whirl and Vortex:” Mid-19th Century Wedding Preparations

by Ann Haddad

This is the third in a series of blog posts on mid-19th century courtship and wedding customs. Click for Part One, on 19th century Courtship, and Part Two, on Marriage Proposals and Engagements.

High Spirits at the Tredwells

Imagine the excitement in the family room of the Tredwell home on a spring evening in late March, 1845. Elizabeth, the eldest daughter of Seabury and Eliza Tredwell, had just named Wednesday, April 9, as the date of her wedding to Effingham Nichols. One can picture Elizabeth and her betrothed, perhaps along with her mother, Eliza, and her sister Mary, seated around the table in the family room, composing the guest list and writing out the wedding invitations. The wedding was only two weeks away, and so much needed to be done! The Tredwell family was about to leap head-on into what one contemporary etiquette manual referred to as “the whirl and vortex” of a wedding. This post will address three important aspects of mid-19th century wedding planning: invitations, the trousseau, and the duties of the groom.

The Transformation of the American Wedding

Elizabeth and Effingham were married in 1845, at a time when the form of the American wedding was gradually transitioning from a simple, family-centered, informal celebration to an elaborate, public, and expensive spectacle. We have no record of their wedding, so it is impossible to know the location, format, or style of their festivities. Seabury, however, given his wealth and social status, could afford to give his eldest and first-wed daughter an elaborate wedding with all the trimmings.

What Wedding Industry?

Up until the mid-19th century, the “wedding industry” (as the providers of services and goods for weddings are collectively known today), barely existed. Because a home wedding was the standard, and the bride’s family hosted the reception, gatherings were usually small and intimate. Many of the items in the bride’s trousseau were made by hand by family members, and the wedding dress was usually the work of a reputable dressmaker known to the family. New York City newspapers from the 1840s featured no advertisements for dedicated commercial wedding “vendors,” or professionals who furnish the trappings of an elaborate wedding. Whereas florists, jewelers, confectioners, and dry goods stores existed, very few items, save for wedding attire, were marketed with a specific eye to wedding celebrations.

This would all change in the late 1850s and especially after the Civil War, as the wedding industry became a huge commercial enterprise, and wedding rituals, especially among upper class families, became more formal, public, and elaborate. Businesses sprang up to cater to the needs of the bride-to-be, including stores that offered ready-to-wear bridal dresses and complete trousseaus. Women were faced with many more choices to consider in every aspect of their wedding, and therefore required more time to shop and plan. Moving the ceremony from the home to a church, along with, some years later, the option of holding the reception in a grand hotel, meant that many more guests could be accommodated; hence, guest lists grew accordingly.

Such Short Notice!

According to wedding etiquette manuals and contemporary diaries, in the first half of the nineteenth century wedding invitations were sent out anywhere from four days to two weeks prior to the wedding date. This short span of time between the date of the invitation and the actual wedding date reflects the simplicity of the wedding form and the minimal advance planning it necessitated.

For example, on Saturday, December 11, 1847, just eight days before her wedding to Andrew Lester, Mary Harris wrote in her diary: “… we were very much engaged in preparing the invitations to be sent next Monday if nothing happens.”

In a letter dated November 1, 1854, from Phebe Tredwell to her sisters (who were at the family summer home in Rumson, New Jersey), she stated: “Shortly after you left on Saturday we received an invitation to Caroline Quackenbush’s wedding next Wednesday from 1 to 3.”

And on November 24, 1855, one month before his marriage to Agnes Suffern, Edward Tailer wrote in his diary: “It will soon be time for us to spend several evenings in directing the invitations.”

The Tredwell/Nichols Guest List

We know neither the size of the guest list for Elizabeth and Effingham’s wedding, nor the names of those invited. Both the Tredwell and Nichols families were wealthy and prominent members of elite New York society. Both had large extended families; Seabury had many former business associates; Effingham had colleagues; and undoubtedly both families had a large circle of friends. So chances are the guest list was long, especially since the Tredwells could accommodate a large gathering in their Greek Revival double parlors, and guests were accustomed to having to cram into the indoor spaces for the festivities.

The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852) warns, however, that any friends denied an invitation to the reception, because of lack of sufficient space, should not feel affronted. Rather, “It is considered a matter of friendly attention to those who cannot be invited, to be present at the ceremony in the church.”

A Sociable, or a Wedding?

Wedding invitations were hand written, in the same style as an invitation to a sociable (the 19th century term for a social gathering). The invitation usually did not announce that a wedding was to be celebrated. This speaks to the rather informal approach taken to the wedding itself, and the fact that most weddings were held in the home of the bride’s parents. So how did guests know to expect nuptials? For one thing, relatives and friends knew of the couple’s engagement, which had gone on for several months at the very least. And once the date had been set by the bride-to-be, both hers and the groom’s families shared the details within their circles by word-of-mouth. In that sense, the written invitation was a formality. In an article on New York fashion in the Buffalo Daily Courier from 1849, a gentleman commented on the speed with which news of a wedding date got around: “It is known in an hour from Union Square to the Battery.”

| .. |

In an 1844 article in the New York Daily Herald, one observant young friend of a future bride detected something in the air:

“For several days previous, the bright and happy faces of the fair ones told me that the gala night was nigh at hand. At length all doubt was removed, when a note of invitation was left at my address, stating that Miss B— would be at home on Wednesday evening, January 3rd; and then I knew that the bridal of one of our fairest maidens was to take place.”

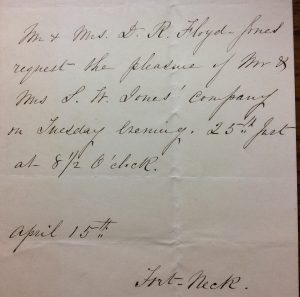

Etiquette dictated that the wedding invitation include only the name of the bride’s parents, the date and the time. In the invitation pictured at left, written on April 15, 1854, for an April 25 wedding, no mention of a wedding is made:

“Mr. And Mrs. D.R. Floyd-Jones request the pleasure of Mr. and Mrs. L.W. Jones’ company on Tuesday evening, 25th just at 8 1/2 o’clock.

April 15th

Fort-Neck”

As the bride was married at her parents’ home, mentioning that a wedding was to take place was deemed unnecessary. Note the evening hour, 8:30 p.m., which was typical for a home wedding.

A church wedding, on the other hand, usually took place in the morning. According to The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness (1860):

“In this case [weddings at church], none are invited to the ceremony excepting the family …”

Additional guests were invited to the reception, held at the bride’s parents’ home following the church ceremony. If Elizabeth and Effingham were married at church, their wedding invitation may have read as follows:

“Mr. and Mrs. Seabury Tredwell

request the pleasure of Mr. and Mrs. Jones’ company,

on Wednesday morning next, at eleven o’clock,

361 Fourth Street [the house number in 1845]

Thursday, April 2nd”

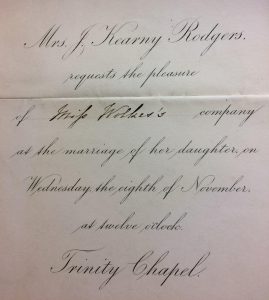

All Those Penmanship Drills Pay Off

In the 1840s, wedding invitations were hand written in a fancy cursive script on white card stock. This was hardly a challenge for well-educated young ladies; excellent penmanship was considered an essential requirement for completion of finishing school. Engraved and printed invitations did not become popular until the early 1860s; ten years later, in keeping with the formality and grandeur of the wedding itself, and more practical given the longer guest lists, such mass produced invitations became de rigueur. Note the engraved invitation (pictured at right) to the 1865 wedding of the daughter of Mrs. J. Kearny Rodgers at Trinity Chapel. Despite the formality of the style, the bride-to-be’s name is not mentioned. One assumes that Mrs. Rodgers had only one daughter!

The Bridal Trousseau

The custom of a bridal trousseau, i.e. the clothing and “soft goods” (such as bed and table linens) that a bride brought to her marriage, became increasingly popular in the mid-19th century. The size of a trousseau depended on the family’s wealth and the position the couple would be assuming in society. For Elizabeth, as the wife of a well-to-do attorney who no doubt had many social obligations, a proper trousseau consisted of a lady’s complete wardrobe (including the wedding gown) sufficient for at least an entire year. This elaborate trousseau assemblage undoubtedly occupied most of Elizabeth’s time prior to her wedding.

According to The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, Fashion, and Manual of Politeness:

“In preparing a bridal outfit, it is best to furnish the wardrobe for at least two years, in under-clothes, and one year in dresses, though the bonnet and cloak, suitable for the coming season, are all that is necessary, as the fashions in these articles change so rapidly.”

Shop ’Til You Drop

Elizabeth no doubt received a sum of money from her father with which to purchase her trousseau. It is impossible to know the cost of a trousseau in 1845, as it varied depending on the family’s social status and financial resources. In 1850, Godey’s Lady’s Book estimated that the cost of the wedding dress and veil alone to be $650. Add to that all the other complements of the trousseau, and one may safely assume that the amount spent on a trousseau by a wealthy family like the Tredwells would be upwards of $1,000 (approximately $30,000 today).

Upon the announcement of her engagement, Elizabeth, assisted by her mother, sisters, and close friends, likely commenced sewing many of the personal items included in the trousseau, such as petticoats, corset covers, nightgowns, dress sleeves, and handkerchiefs. Once her wedding date was set, the shopping began with a vengeance at popular dry-goods stores, such as A.T. Stewart, then located on Broadway near Chambers Street, and Lord and Taylor, then located on Catherine Street. These emporiums stocked many trousseau items in addition to dresses, such as sewing implements, linens, shawls, slippers, and hair combs and brushes.

In the short story Incompatibility of Temper, by Alice B. Haven, published in the January 1862 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book, the author describes how the bride’s trousseau has taken over one bedroom:

“The best bedroom was draped with the new dresses that had been made up with much thought and consultation of the fashion magazines; the clothes-press was entirely occupied by the wedding dress itself, over which a sheet was carefully hung to protect it from all possible contact with dust or flies; and Marie’s own drawers were overflowing with the four dozen cotton and two dozen linen, to say nothing of nightcaps, which were at least happily completed. There were twenty things to be done yet …”

The Most Important Item of a Trousseau: the Wedding Dress

According to the August 1849 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book, the “etiquette of trousseau” dictated that a fashionable wedding dress be made of white silk or satin, with a Brussels lace over-dress with a fitted bodice and full skirt. A white veil, long and full, and most likely made of Brussels lace, was attached to an artificial wreath of orange blooms (popularized by Queen Victoria, who wore them at her wedding in 1840) that encircled the head. Flat white satin or silk slippers decorated with ribbons; white silk stockings; short white kid gloves; and an embroidered handkerchief (perhaps with interlaced initials of the bride and groom), completed the ensemble.

According to etiquette manuals such as The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility (1846), jewelry was practically forbidden: “She should wear no ornaments but what her intended or father should present her for the occasion.”

In a letter sent by a “Sarah” from Manhasset, Long Island to Ida A. Coles, dated April 18, 1847, she wrote:

“She [the bride] has ten new dresses and some of them are very handsome. The wedding dress is white satin with an embroidered lace over, it is beautiful. She has not purchased her veil as yet.”

Dressmaker Required

Eliza Tredwell most likely hired a dressmaker to create Elizabeth’s wedding ensemble. The seamstress may have lived with the family for a few weeks before the wedding, sewing the dresses in return for room and board, or for a set fee. Imagine the excitement with which Elizabeth and her mother examined the latest silk and satin fabrics, imported from France and widely available at the many dry-good stores that catered to ladies’ fashions, such as H. Myers & Gedney, located at 375 Broadway.

Elizabeth’s fine white bridal slippers may have come from J.B. Miller’s shoe store, located at 142 Canal Street, which in 1844 advertised “White and Black satin, also french, Morocco and Kid slippers, for Balls, Parties, Weddings, &c.”

Ready-to-wear bridal dresses were not widely available in stores until the 1860s, but the earliest advertisements for “wedding dresses,” as distinct from dresses for other occasions, and made in France, appeared in New York newspapers by the mid-1840s. One enterprising woman was selling them in 1844, according to an advertisement in the New York Daily Herald:

“Madame N. Scheltema informs her customers … that she has just received per last Havre packet, a new and splendid assortment of rich embroidered and other Wedding Dresses.”

James Beck & Co., and William A. Smets, two dry-goods stores located on Broadway, advertised “Wedding and Soiree Dresses.” Shops like these, however, no doubt catered to the wealthy upper class, who could afford the fine items sold there. The Tredwell family probably patronized these establishments.

Dressing the Rest of the Family

One can only imagine Eliza’s state of mind in the weeks before her daughter’s wedding. Not only did she have to oversee Elizabeth’s trousseau and all it entailed, she was also faced with the daunting task of dressing herself and her FIVE other daughters! There were new ensembles to be purchased (white dresses for those sisters chosen to be bridesmaids); and a hairdresser to be engaged for Eliza, Elizabeth, and perhaps Elizabeth’s sister Mary (who at 20 was considered a young lady). Her wealth would have allowed Eliza to hire a dresser to assist the women with their toilettes.

Eliza also bore the responsibility of making sure that Elizabeth’s younger brothers Horace and Samuel (ages 21 and 18, respectively), were properly attired. Whether or not they were groomsmen, because of their age their outfits would have been very similar to Effingham’s (described below).

Mrs. Abiel Abbot Low, a wealthy woman who lived in Brooklyn Heights, recorded in her diary the extensive preparations for the wedding of a family member, to be held on Sunday, February 2, 1845 (just two months before Elizabeth’s wedding). She made frequent trips by coach back and forth from her home in Brooklyn to Manhattan for this purpose. On Thursday January 23, 1845, she wrote: “I selected a superb silk dress at Stewart’s to wear to Josiah’s wedding.”

Several days later, on Thursday January 30, she noted: “I went to New York to engage Martelle to dress my hair for the wedding, but he was engaged for the time that I needed him. I bought a pretty evening fan …”

What Does Effingham Do?

Compared to Elizabeth’s multiple wedding chores, Effingham had relatively little to do. As his father, the Reverend Samuel Nichols, was to perform the wedding ceremony, it spared him the headache of having to track down an available rector, as Henry Patterson indicated in his diary on July 14, 1844, one week before his wedding:

“I made an engagement with Mr. Edwin Hatfield pastor of the Presbyterian Church, corner of Broome and Ridge Street, to perform the marriage ceremony for us, next Thursday evening at eight o’clock. I endeavored to get Mr. Bellows or Mr. Dewey, but they are both absent from the city.”

Custom dictated that the groom was also responsible for finding a suitable home for his bride. Effingham was spared this task, however; after the wedding and travel (if any) he simply joined his bride at the Tredwell home on Fourth Street. It was not atypical for newlyweds to live with family, which gave a man time to establish himself in business before buying a home.

If a “wedding tour” (as it is called in The Art of Good Behavior) was planned for after the marriage, Effingham made the arrangements, including clearing his work schedule for anywhere from two weeks to one month to accommodate his absence.

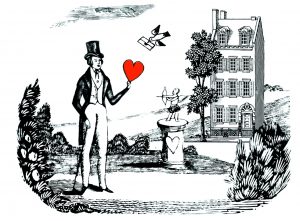

Effingham Gets Dressed Up, Too

Men’s fashion in the 1840s was characterized by low, tightly cinched waists; snug waistcoats and trousers; high collared shirts tied with a cravat; and flared frock-coats. The groom’s attire is described in The Art of Good Behavior:

“The bridegroom must be in full dress, black or blue dress coat, which may be faced with white satin; a white vest, black pantaloons, and dress boots, or pumps, with black silk stockings, and white kid gloves, and a white cravat. The groomsmen should be dressed in a similar manner.”

In the 1840s, a colorful, embroidered waistcoat was a fashionable item in a groom’s attire. The waistcoat was occasionally worked by the bride, and presented as a wedding gift to the groom. Elizabeth may have shopped at William T. Jennings on Broadway, which advertised in 1844, “a lot of rich silk and satin vestings, suitable for ball and wedding vests,” for material for Effingham’s waistcoat.

Destroy the Evidence!

The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony also strongly recommended that a gentleman begin his marriage with a clean moral slate, by divesting himself of certain bachelor friends whose company would not be deemed fitting for a newly married gentleman. Burning one’s bachelor letters is also considered essential, for: “Not to do this might hereafter lead to inconvenience.”

Not a Whisker Out of Place

One other concern may have occupied Effingham’s mind before the wedding. If he sported whiskers, they must be neat and full by his wedding day. So, he may have followed the lead of Henry Patterson, who on Sunday, May 19, 1844, approximately two months before his wedding, wrote in his diary: “I cut off my whiskers, intending immediately to let them grow again, so as to have a new sett [sic] on my wedding day.”

With This Ring I Thee Wed

The task that probably had the greatest significance for Effingham was purchasing Elizabeth’s wedding ring. The fashion for wedding bands was plain, thick gold. Although jewelry store advertisements were plentiful in newspapers in 1845, only one, William Wise, located at 79 Fulton Street in Brooklyn, offered “gold wedding rings” for sale. To ensure that the ring was properly sized for his bride, according to the Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony, the man must: “… get a sister of your fair one to lend you one of the lady’s rings.” One can just picture Effingham convincing Mary to secretly remove a ring from Elizabeth’s jewelry box!

In the poem “The Bridal” (1849), which one may imagine had been written with Elizabeth and her sisters in mind, one finds reference to the wedding ring:

“Oh! They are blest indeed, and swift the hours

Till her young sisters wreathe her hair in flowers.

Then before all they stand; the holy vow,

And ring of gold—no fond illusion now—

Bind her as his.”

Stay tuned: the next blog post will cover the wedding day!

|

Sources:

- Anonymous. The Art of Good Behavior, and Letter Writer, on Love, Courtship, and Marriage: A Complete Guide. New York: Huestis & Cozans, 1845. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society.

- Anonymous. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony. London: David Bogue, 1852. books.google.com. Accessed 1/18/18.

- Bradford, Isabella. “A Fashion Worth Revisiting? A Bridegroom’s Embroidered Wedding Waistcoat, 1842.” Two Nerdy History Girls. Tuesday, November 11, 2014. www.twonerdyhistorygirls.blogspot.com. Accessed 4/4/18.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Wednesday, March 5, 1845, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/6/18.

- Coles Family Papers, 1803-1859. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- David R. and Mary Floyd-Jones Invitation, 1854 April 15, Floyd-Jones Papers. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Emily Hosack Rodgers Collection, 1848-1888. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- “Etiquette of Trousseau.” Godey’s Lady’s Book. August, 1849.

- The Evening Post. Tuesday, 16 January, 1844, p. 3. www.nespapers.com. Accessed 3/6/18.

- The Evening Post. Friday, 26 January, 1844, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/13/18.

- The Evening Post. Friday, 6 September, 1844, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/6/18.

- The Evening Post. Saturday, November 16, 1844, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/21/18.

- The Evening Post, Monday, 10 March, 1845, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/30/18.

- Hartley, Florence. The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, Fashion, & Manual of Politeness. Boston: G.W. Cottrell, 1860. www.gutenberg.org. Accessed 3/15/18.

- Haven, Alice B. “Incompatibility of Temper.” Godey’s Lady’s Book. January, 1862.

- Lester, Mary H. Diary, 1847-1849. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Low, Harriet. Diary, 1844-45, Low Family Papers, 1750-1900. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- New York Daily Herald. Tuesday, 27 February, 1844, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/13/18.

- New York Daily Herald. Saturday, May 18, 1844, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/11/18.

- New York Daily Herald. Thursday, April 24, 1845, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/16/18.

- “New York Fashions.” Buffalo Daily Courier. Monday, 5 November, 1849, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/18/18.

- New York Tribune. Saturday, 28 December, 1844, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/7/18.

- O’Neil, Patrick W. Tying the Knots: The Nationalization of Wedding Rituals in Antebellum America. Dissertation Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2009. www.cdr.lib.unc.edu. Accessed 3/15/18.

- Patterson, Henry. Diaries, 1832-1848. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Pinckney, Cotesworth, ed. The Wedding Gift, To All Who are Entering the Marriage State. Lowell: Milton Bonney, 1849. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 4/5/18.

- Reeves, Emma. History of the Bridal Trousseau. September 15, 2016. www.theribboninmyjournal.com. Accessed 3/18/18.

- Rothman, Ellen K. Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Tailer, Edward Neufville. Diaries, 1848-1917. Manuscripts Division, New York-Historical Society.

- Thornwell, Emily. The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility: In Manners, Dress, and Conversation. New York: Derby & Jackson, 1856. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/17/18.

- Tredwell, Phebe. Letter, November 1, 1854. Nichols Family Papers. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “History of Fashion 1840-1900.” www.vam.ac.uk. Accessed 4/4/18.

- Wallace, Carol McD. All Dressed in White: The Irresistible Rise of The American Wedding. New York: Penguin Books, 2004.

- “Wedding Memories: The Bride’s Trousseau.” Magpie Wedding. www.magpiewedding.com. Accessed 4/9/18.

Mine and Mine Only: The Marriage Proposal and Engagement

by Ann Haddad

This is the second in a series of blog posts on mid-19th century courtship and wedding customs. Click here to read the first post, on 19th century courtship.

A Horse and a Wife

Charles A. Bristed, in his satirical sketch of American society, The Upper Ten Thousand (1852), noted:

“The first thing, as a general rule, that a young Gothamite does is to get a horse; the second, to get a wife.”

Although it is uncertain if Effingham Nichols owned a horse, he did indeed acquire a wife, the bride being none other than Elizabeth Tredwell, eldest daughter of Seabury and Eliza Tredwell. Effingham was only two years into his law practice, located on 7 Nassau Street, when he wed the very eligible 23-year-old Elizabeth on April 9, 1845. We do not know the duration of their courtship, but Effingham must have received significant encouragement from the young lady during that time, emboldening him to declare his love and to propose marriage.

Never Flirt!

Asking a young woman for her hand in marriage was never perceived as an easy task for a gentleman. After all, his fate rested in her hands! For this reason, the etiquette manuals of the day warned women repeatedly not to trifle with a young man’s affections, lest it earn the woman the dreaded reputation of being a flirt. If a gentleman’s behavior towards a woman conveyed romantic feelings, and she did not wish to encourage him, she was to do her utmost to gently rebuff his sentiments in a kindly manner, and gradually withdraw from his company. An honorable woman never shared (except with her parents) that she had rejected a suitor. As A Manual of Etiquette (1868) stated:

“If you possess either a decent generosity, or the least good breeding, you will not divulge a secret which should be sacred between you.”

Passing the Test

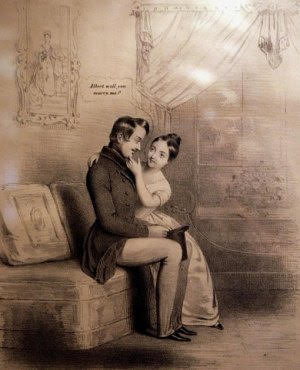

| … |

After their courtship had gone on for an appropriate period (etiquette manuals were reluctant to establish the proper length of the courtship period), a woman who found the attention from her suitor more than agreeable indicated in unspoken ways that a proposal of marriage would be welcome. She, of course, could not propose to a gentleman (only queens were permitted to do so; Queen Victoria notably proposed to Prince Albert); but, according to the Dictionary of Love (1858):

“… she may lawfully do all in her power to put him in the notion of proposing. She may be very glad to see him when he calls, she may gently chide him for staying away so long ‘We feared you had forgotten us,’ or she may, by the purest accident, always happen to get a seat very near him whenever she is in his company. It is clearly a lady’s right to modestly open the way for the approaches of a gentleman whose heart she honorably wishes to obtain.”

A young lady’s father (especially a wealthy one like Seabury Tredwell, who needed to protect his daughter from fortune hunters) had already assessed the suitor’s finances (were his prospects good enough to provide a home for and support a wife and children?), scrutinized his lineage (did he come from a reputable family?), and deemed him acceptable. At this point, it was safe and indeed incumbent on the young man to seize the opportunity and proceed with a proposal. As stated in The Art of Good Behavior (1846), a popular etiquette manual:

“As a general rule, a gentleman need never be refused. Every woman, except a heartless coquette, finds the means of discouraging a man whom she does not intend to have, before the matter comes to the point of a declaration.”

An unidentified young clerk in New York City indicated his confidence that he had a future with his beloved Julia when he wrote in his diary on October 13, 1844:

“Was much amused at a remark Julia made. She said ‘I don’t know how to take you.’ I replied ‘Take me as I am.’ She answered, ‘I expect I shall be obliged to.’ It may be a prophetic remark.”

Once the suitor determined that his offer of marriage would be welcomed, there was nothing left to do but “pop the question” (an idiom in use since 1826). The Art of Good Behavior perfectly captured the anxiety of the moment:

“… and though he may tremble, and feel his pulses throbbing and tingling through every limb; though his heart is filling up in his throat, and his tongue cleaves to the roof of his mouth, yet the awful question must be asked.”

Will You Marry Me?

Should a gentleman find elusive the right words with which to propose, he needed only consult one of the popular etiquette manuals, which offered many suggestions. Here are some from The Art of Good Behavior:

“Will you tell me what I most wish to know!”

“Yes, if I can.”

“The happy day when we shall be married?”

“Have you any objection to change your name?” “How would mine suit you?”

“One word from you would make me the happiest man in the universe.”

“Well, Mary, when is the happy day?” “What day, pray?” “Why, everybody knows we are going to get married, and it might as well be one time or another; so, when shall it be?”

And then there was the laconic gentleman who, according to the Evening Post of August 14, 1840, proposed in the following manner:

“Pray, madam, do you like buttered toast?” “Yes, sir.” “Buttered on both sides?” “Yes, sir.” “Will you marry me?”

The joyous declaration of love was described in the Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852):

“The happy moment of opportunity arrives, in sweet suddenness, when the flood gates of feeling are loosened, and the full tide of mutual affection gushes forth uncontrolled.”

James R. Burtin, a young New York gentleman who worked as an engraver, recorded in his diary the exciting moment when, after nearly two years of courtship, he proposed to his beloved Ann Elisa on February 18, 1844:

“This is an evening I shall always remember with mingled feelings of pleasure and pain. One question I asked my dear Ann, the answer of which depended my future happiness or misery and she hesitated to answer it. It was a moment of suspense tho if she knew how I loved her and how dear she is to me she would have given me an answer at once. I did not doubt but that her answer would be such as one as I wish and the answer was one that put all doubt aside. She loves truly and I love her and whatever may take place I shall love her as long as life shall last. She is dearer to me than Mother, brother or Sister. Without her I may almost say that life would be unendurable, but now all doubts are at an end. She is mine and mine only.”

Put It in Writing

For those timid, tongue-tied gentlemen who could not bear the thought of proposing in person, etiquette manuals, such as the American Fashionable Letter Writer (1845), also offered sample proposal letters, such as:

“Every one of those qualities in you which claim my admiration, increased my diffidence, by showing the great risk I run in venturing, perhaps before my affectionate assiduities have made the desired impression upon your mind, to make a declaration of the ardent passion I have long since felt for you.”

On October 28, 1843, Henry Patterson, a contemporary of Burtin’s, wrote in his diary about his written proposal of marriage to Eleanor Wright:

“Last week Thursday I made proposals of marriage to her in writing; Sunday evening I received a conditional acceptance, also in writing, and Wednesday evening we spent in unfolding to each other our situation, prospects, hopes, principles, feelings, in short everything which would tend to a judicious and proper settlement of the question now the subject of our joint consideration. I will only record, that as I become acquainted with her, I become more thoroughly convinced of our suitableness to each other; and the outpouring of tender feelings which I enjoyed on Wednesday evening, that sensation of mutual love and trust which I have since felt within us, renders the present the happiest period of my life.”

| … |

I’ll Get Back to You

When a gentleman made an offer of marriage either in person or by letter, it was incumbent upon the young lady to receive it graciously. She knew, either by instruction from her parents or by the advice provided by etiquette manuals, never to accept or reject the offer immediately. Such an important decision merited deep reflection, and discussion with her parents, whose consent was necessary before any answer was given. As Farrar reminds her readers in The Young Lady’s Friend (1837):

“It should be an avowed principle of your life, that you will never marry without the consent of your parents, nor merely to please them.”

If the young lady’s parents opposed the match, the couple carefully considered the objection, and perhaps delayed their marriage until the reason for the disapproval had been overcome.

The American Fashionable Letter Writer provided an example of a young lady’s written reply to a proposal of marriage:

“There are many points beside mere personal regard to be considered; these I must refer to the superior knowledge of my father and brother, and if the result of their inquiries is such as my presentiments suggest, I have no doubt my happiness will be attended to by a permission to decide for myself.”

Man to Man

After proposing marriage, the next daunting step for the gentleman was a formal meeting with the woman’s father, to officially ask for his consent to the marriage. It is noteworthy, with regard to parental consent, that the opinion of the young woman’s parents appears to be the only one that matters. None of the diaries consulted for this post made any mention of the suitor’s parents in any aspect of the courtship or engagement. As Ellen K. Rothman concluded in Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America (1984), “A woman’s parents were asked; a man’s parents were told.”

Seabury Tredwell was probably not surprised when Effingham Nichols entered his study to request Elizabeth’s hand in marriage; he most likely was expecting it. Effingham would have been prepared to discuss his law practice, his future prospects, and his financial situation in detail. He was, after all, responsible for providing a stable economic environment for Seabury’s daughter; it was critical that he explain how he planned to go about this. Seabury already knew Effingham came from an excellent family, and must have been willing to accept Effingham’s status and envision his future success. Imagine the joyful scene on Fourth Street when, once Seabury gave the couple his blessing, Elizabeth and Effingham shared the happy news with her mother, Eliza, and her siblings!

The parents of Eleanor Wright, the young woman with whom Henry Patterson was in love, were separated (separation and divorce were not as uncommon as we might think — a topic for a future blog post). That may explain why it took two months for Henry to meet with her father. On December 30, 1843, he wrote:

“By mutual agreement that it was advisable, I called the next morning on her Father, in Fifth Street, and briefly acquainted him with my past intercourse with his daughter and my plans for the future; I asked his approval. He expressed his approbation as far as he was acquainted with the circumstances, and treated me in every respect in a gentlemanly manner.”

We have no idea what Elizabeth’s siblings thought of her suitor, Effingham Nichols. The opinion of brothers and sisters held little weight when it came to choosing a mate for life. Elizabeth Brevoort was a young girl of fourteen when on July 31, 1848, she wrote in her diary of her sister’s love interest:

“I must say it is not the marriage I wish for her but if she thinks she will be happy with him, I am sure it is none of my business.”

The Engagement Period

Patrick W. O’Neil, in his dissertation thesis, Tying the Knots: The Nationalization of Wedding Rituals in Antebellum America (2009), described the engagement period (which typically lasted from six months to two years, depending on the family circumstances and the age of the couple) as a moment of transition between courtship and married life wherein couples could come to a full understanding of the meaning behind their commitment to one another. It was viewed as an opportunity for the lovers to imagine themselves married, and to declare their suitability to the world. In doing so, they experienced a loosening to some extent of the restrictive bonds of decorum, and hence were able to deepen their knowledge of each other. O’Neil cautioned, however, that the easing of rules in this rigid society only went so far:

“None of this is to say that the middle-class men pursued gender equality in their married relationships: they would not have taken kindly to assertions of autonomy from their future wives.”

In the mid-19th century, once the young lady and her parents consented to the marriage, the announcement of the engagement was initially made to family and intimate friends only; this was typically done in writing. This allowed all involved to take a collective breath and live with the idea; it would be during this time that either party could gracefully break off the engagement without doing widespread damage. After a week or two, the wider circle of friends and acquaintances would receive news of the engagement.

The Ring-Bearers

According to Ellen Rothman, in Hands and Hearts, the custom of presenting one’s betrothed with a ring upon engagement began in the 1840s. The simple bands, which sometimes included a cut stone, were mutually exchanged; they served as a public sign of the couple’s commitment to each other. Occasionally, another personal token, such as a portrait miniature of the future bride, was presented to the groom-to-be in place of a ring. Diamond engagement rings as we know them today did not become popular until Tiffany & Co. introduced the Tiffany setting in 1886.

Behave Yourselves

Not surprisingly, the conduct of a betrothed couple was also governed by a strict protocol. When in public, any overt signs of familiarity and exclusivity were forbidden. The gentleman was to behave gallantly and honorably toward any woman in his presence, not just to his fiancée; and his future bride refrain from pouting or reacting with jealousy and anger when he did so. That didn’t mean, however, that the gentleman refrained from being protective of his sweetheart, or that she ignored him. Ideally, they presented to the world an image of blissful and contented happiness. Although the couple did not isolate themselves from the society of others, the woman was careful to avoid spending time with any other man in private. When attending sociables and other entertainments in the absence of her betrothed, etiquette dictated that she be accompanied by a family member or intimate family friend.

In private, a gentleman never took advantage of his bride-to-be, for he had her honor to maintain. As the Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852) pointed out: “he is dealing with his future wife.” Whenever he was in the presence of his betrothed, it was a young man’s duty to avoid any display of fatigue, low spirits, or “excessive animation.” Several etiquette manuals also discussed the engagement period as a time when a gentleman bore the responsibility of advising and guiding his betrothed, by correcting her faults and helping to mold her character. It was the rare mid-19th century treatise, such as Mrs. A.J. Graves’ Woman in America (1858) that challenged this notion, stating, “woman was not given to a man for a toy to amuse his idle hours; but to be, in truth and in reality, a helpmate to him – a minister for good.”

The Welcome Mat

Once the engagement was underway, the gentleman was expected to pay frequent calls at his bride-to-be’s home. He was to ascertain, however, the time most convenient for his call; and when he visited, he was to focus attention on the entire family, not just on his betrothed. His aim in making the calls was to gradually win the affection of the family, especially the girl’s mother. The visits were usually made in the evening, with the gentleman wearing evening attire, as he would for the theatre or a concert. As the Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony stated,

“The neglect of this point would betray, first, a carelessness in habits, next, a want of deference to the lady’s family, and lastly, a deficiency in due respect to herself.”

According to their diary entries, both Henry Patterson and James Burtin could be found almost nightly at the homes of their betrothed. Often they had tea with the family in the afternoon and then return in the evening! Burtin, who had made a habit of frequent visits even before his engagement, wrote in his diary on November 16, 1843:

“I am inclined to think that love makes a fool of a man , that is in other people’s estimation, but what is the use. I love Ann Elisa and when I can see her there is not the least doubt but that I will.”

| .. |

Stealing a Kiss

Despite the protocol set forth in popular etiquette manuals, evidence in diaries of this period indicates that betrothed couples were frequently left alone in the young lady’s home, often until 1 or 2 a.m. Henry Patterson and Eleanor Wright spent many evenings alone in her parlor, playing chess, whist, reading to one another, and ultimately exchanging mutual affection. On January 21, 1844, he wrote:

“Monday evening I spent with Eleanor, with chess, reading, and conversation, all of which, having mingled with them expressions of the most tender love and kindest feelings, served to render that evening one of the happiest seasons of my life.”

James Burtin even exercised with Ann Elisa, as he wrote on his diary on May 25, 1843:

“In the evening called over to see Ann Elisa found her jumping the rope joined in with her and had some fine exercise but found it rather warm work.

“This is a Waste of Our Time”

Once betrothed, couples were permitted to go out together unaccompanied: for walks on the Battery; to concerts at Niblo’s Garden; to museums, theatre, church, lectures, and to weddings of friends and family. After months of such activity, with no wedding date yet set, Henry Patterson was growing increasingly frustrated. He wrote in his diary on March 24, 1844:

“Oh! how tired and impatient I feel, to be thus compelled to take a part in amusements, and join in company for which I feel no affinity. Enjoying alone Eleanor’s society, with no restraints on the interchange of tokens of love, is almost the only thing that is at all satisfactory to me: how painful to me that this is a waste of our time, in foolery, and empty amusements. Yet, may it not be played upon us to exercise our patience, and and learn us to prize more highly and justly the unspeakable blessing which we do enjoy?”

Fixing the Day

The days of idle amusements were soon over for Henry and Eleanor; once their marriage date was set (by the woman, this being one of her express privileges), they found themselves busier than ever. There was a household to set up, a trousseau to purchase, and a wedding to arrange. As the wedding industry was in its infancy, it was typical for a wedding date to be announced only two to three weeks prior to the actual date. As a result, the wedding preparations were intense and extensive, requiring hard work by both parties. The burden, as we shall see, rested more on the woman’s shoulders, for as Rothman points out in Hands and Hearts: “While engagement interfered with a man’s work, it was a woman’s work.”

Sources:

- Anonymous. The American Fashionable Letter Writer, Original and Selected. Troy, N.Y.: W. & H. Merriam, 1845. www.catalog.hathitrust.org. Accessed 3/1/18.

- Anonymous. The Art of Good Behavior, and Letter Writer, on Love, Courtship, and Marriage: A Complete Guide. New York: Huestis & Cozans, 1845. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society.

- Anonymous. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony: With A Complete Guide to the Forms of a Wedding. London: David Bogue, 1852. www.books.google.com. Accessed 2/2/18.

- Arthur, T[imothy]S[hay]. Advice to Young Ladies on Their Duties and Conduct in Life. Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1847. babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 1/16/18.

- Brevoort, Elizabeth. Diary, 1848. Rare Books and Manuscripts Division, New York Public Library.

- Bristed, Charles Astor. The Upper Ten Thousand; Sketches of American Society. London: Parker and son, 1852. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 2/13/18.

- Diary of an Unidentified Clerk in New York City, 1844-45. MssCol. 2147, Rare Books and and Manuscripts Division, New York Public Library.

- Diary of an Unidentified Young Man [James R. Burtin], January 1, 1843- 1844. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Farrar, Mrs. John. A Young Lady’s Friend. Boston: American Stationers’ Company, 1838. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/23/18.

- Graves, Mrs. A.J. Woman in America; Being an Examination into the Moral and Intellectual Condition of American Female Society. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1858. www.catalog.hathitrust.org. Accessed 3/2/18.

- Johnson, S. O. [Sophia Orne]. A Manual of Etiquette with Hints on Politeness and Good Breeding. Philadelphia: D. McKay, 1868. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/26/18.

- O’Neil, Patrick W. Tying the Knots: The Nationalization of Wedding Rituals in Antebellum America. Dissertation Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2009. www.cdr.lib.unc.edu. Accessed 3/1/18.

- Patterson, Henry. Diaries, 1832-1848. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- “Popping the Question.” The Evening Post, Fri., August 14, 1840, p. 2. www.newspapaers.com. Accessed 2/28/18.

- Rothman, Ellen K. Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1984.

- Theocritus, Junior [pseud.]. Dictionary of Love. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1858. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/5/18.

- “Tiffany and Co. History,” Tiffany & Co. www.press.tiffany.com. Accessed 3/2/18.

Romance and Sweet Dreams: Mid-19th Century Courtship

by Ann Haddad

.

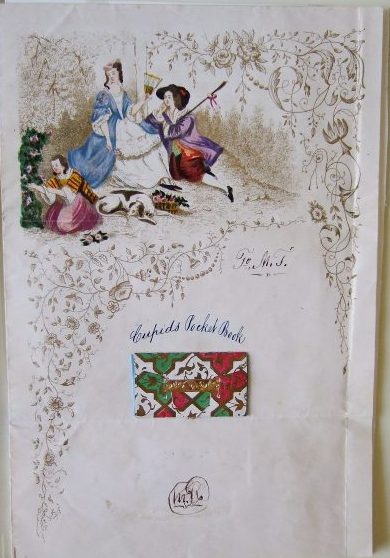

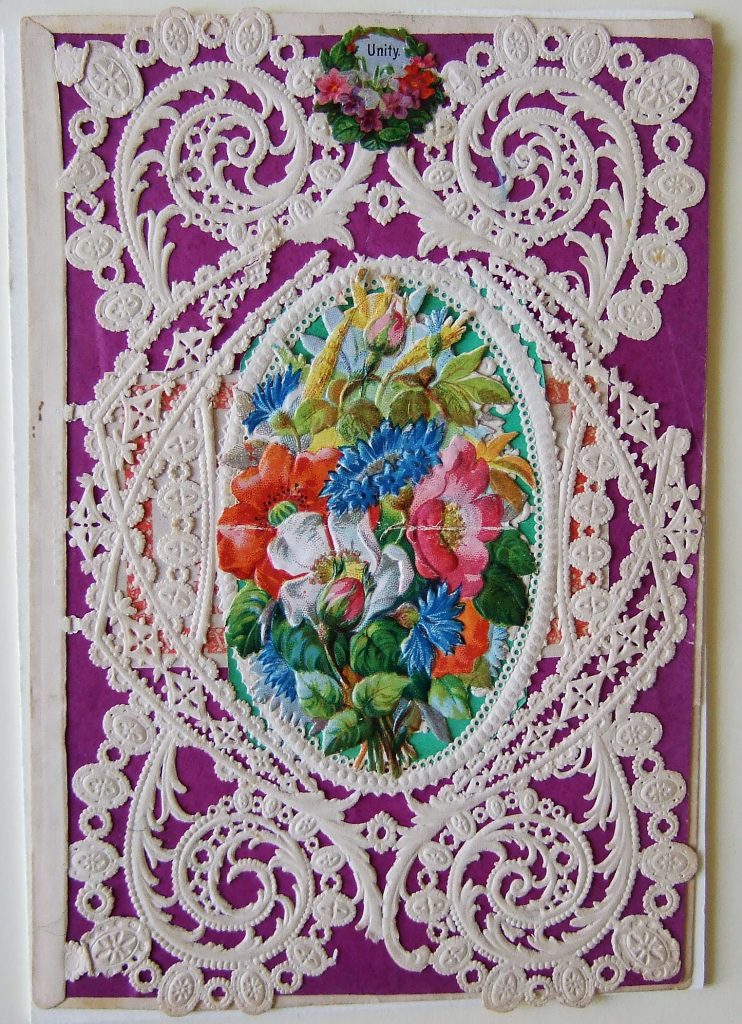

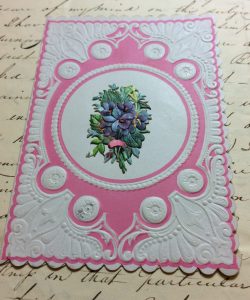

Valentines for an Eligible Lady

Valentine’s Day has been celebrated for centuries, but only became entrenched in American culture in the early 1840s, with the rise in popularity of commercially produced paper valentine cards. Made of delicately embossed and perforated lace papers, valentines became the fashionable way to convey romantic interest and to freely express the desire for romantic love.

The lovely Elizabeth Tredwell, eldest daughter of Seabury and Eliza, no doubt received her share of valentines from young men of her class. She was pretty and accomplished, and would certainly have been considered an eligible young lady. The Tredwell Archives contain several charming valentines; however, the senders and recipients are unknown.

On April 9, 1845, Elizabeth married Effingham Nichols (see our April 2017 blog post, “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing: The Marriage of Elizabeth Tredwell and Effingham Nichols”). We do not know when and how Elizabeth and Effingham met, nor are we aware of the length of their courtship. Based on the many strict codes of etiquette that governed courtship, however, we can assume theirs followed a dictated course.

.

.

.

Romantic Love

In the mid-19th century, romantic love was viewed as the solid rock upon which a healthy marriage was built; according to Karen Lystra, author of Searching the Heart (1989), it was only within the sacred state of marriage that one’s “ideal self” could be revealed. Courtship, therefore, was respected as a special time in the lives of a young couple. This period, after introductions and before a formal engagement, served to intensify the feelings of romantic love; to insure that the bond formed between a couple was true; to guide one in learning the real character of the other; and to ensure that their attraction was based on mutual respect and admiration. In Theocritus’ The Dictionary of Love (1858), it is defined as the period that is “all romance, excitement, hope, desire, expectation, and sweet dreams.”

Before Courtship: Under Mama’s Watchful Eyes

The time for a young woman to enter society and assume her role as a marriageable woman was determined by her parents; it depended not on her age, but on her level of maturity. A woman was also expected to have completed her education, or “finishing,” typically between the ages of 16 and 18, before entering society. Elizabeth most likely went “into company” (or “came out,” as it was later called) sometime around the age of 20.

Courting before this age was highly frowned upon. After completing her schooling, a daughter remained at home (which was viewed as a woman’s empire), under the watchful eyes of her mother. Here she learned domestic arts; assisted with rearing her younger siblings; and was instructed in the rules of manners and civility, which were highly valued in society. A young lady was chaperoned at public entertainments, such as theatre or dances, by her parents, brothers, or an intimate family friend. (Once she became formally engaged, her lover became her “legitimate protector and companion.”) She was expected to rebuff any male attention, and maintain a polite disinterest in courtship. Mrs. John Farrar, in A Young Lady’s Friend (1837), writes,

“The less your mind dwells upon lovers and matrimony, the more agreeable and profitable will be your intercourse with gentlemen. Regard men as intellectual beings who have access to certain sources of knowledge to which you are denied.”

Elizabeth also received guidance from her mother (likely culled from popular advice books such as Lydia Maria Child’s The Frugal Housewife (1829); Godey’s Lady’s Book; and etiquette and conduct manuals) about acceptable behaviors that reflect what Mrs. John Farrar called “delicacy and refinement” when in the company of young men. Never let a man hold your hand; decline his offer of assistance with getting in and out of carriages; never squeeze into a tight space with a gentleman; never speak of your private affairs or feelings; always have a friend present for carriage rides; never borrow money from a man; avoid gossip. Mrs. Farrer stressed:

“Your whole deportment should give the idea that your person, your voice, and your mind are entirely under your own control. Self-possession is the first requisite to good manners.”

Above all, a young lady was never to make obvious public plays for the attention of a young man, or insinuate that she wanted an invitation from him. According to T.S. Arthur, author of Advice to Young Ladies (1847), such inappropriateness indicated “an outrageous want of all decent respect for herself.”

Money and Religion

Aside from the usual parental concerns associated with finding a suitable partner for their daughter, Seabury and Eliza Tredwell had another reason to be extremely careful when vetting young men who were interested in courting Elizabeth: the family’s enormous wealth. Guarding against any unprincipled suitor who viewed a fortune as indispensable when choosing a wife was no doubt of utmost importance. They therefore sought to find a husband for Elizabeth whose own wealth was equal to or greater than her own. Similarity of religion was also considered to be a requisite; whoever sought and won Elizabeth’s hand had to be of the Episcopal faith (see our February 2017 blog post, “The Man That Got Away,” for a discussion of the aborted romance of Elizabeth’s youngest sister, Gertrude, and Luis Walton).

A Formal Introduction

A gentleman did not consider courting a woman unless he had been formally introduced to her. (Men were not without their etiquette manuals: Lord Chesterfield’s Advice to His Son on Men and Manners, first published in 1774, was the popular source.) Effingham may have been introduced to Elizabeth through her father or one of her uncles, or through a respected friend of the family. For those without known connections, it was the gentleman’s task to respectfully make her acquaintance. Upon noticing a woman at a dance, for example, he first learned her name by making discreet inquiries, and then, through his societal connections, asked for an introduction. As the couple became acquainted through conversation, the gentleman ascertained the woman’s level of interest, and whether any further attentions were welcome.

Dear Mr. Tredwell

If he perceived that she was not averse, and he was confident that his position in life and circumstances were sufficient to allow him to proceed, a gentleman took the next step — writing to the woman’s father to ask permission to pay a visit to their home. In this important communication, he stated his position and prospects, and mentioned his family. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852) cautioned the suitor against any smugness or over-confidence at this stage:

“Never think you are doing the family a favor. A man must convey delicate respect towards the parents, to prove himself worthy of the treasure of which he is about to deprive them.”

The following portion of a sample letter from The Art of Good Behavior (1845) may be similar to one sent to Seabury Tredwell from Effingham Nichols, when he desired to begin courting Elizabeth:

“The subject upon which I presume to address you is one so near to my heart, and so connected with my prospects of happiness in this life, that I find it difficult to summon resolution for the task; but sir, I have dared to entertain so high an opinion of your goodness, that I am emboldened to write to you with candor, to solicit the greatest favor it is in your power to bestow.”

Emily Thornwell, in The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility (1856), defined the proper look of a letter from a potential suitor to a young woman’s father:

“Observe that letters of introduction are never sealed by well-bred people. Every letter to a superior ought to be folded in an envelope. It shows a want of respect to seal with a wafer; we must use sealing wax; men usually select red.”

Once permission was obtained from the father, the young lady in question then extended a letter to the gentleman, inviting him to pay a call. She avoided displaying any excessive interest in him, however. Thornwell emphasized the importance of restraint:

“You should not remark to a gentleman, ‘I am very happy to make your acquaintance;’ because it should be considered a favor for him to be presented to you, therefore the remark should come rather from him.”

The Trial Period

As soon as the father established that a young gentlemen was suitable company for his daughter (accomplished through inquiries among his set as to the family and status of the suitor), courtship commenced. In the young lady’s front parlor, with a chaperone present, a courting couple engaged in allowed activities including singing, talking, piano playing, and parlor games with other guests. Supervised carriage rides and outdoor excursions to dances, picnics, dinners, and concerts were also permitted. During this time, the couple observed one another’s habits and conduct for evidence of good moral character and virtuous principles, and hence suitability.

A woman considered positive traits, such as a man’s ability to speak with ease, respect, and courtesy to all; a neat appearance; excellent manners and deference to all women; and his readiness to honor and defend the opposite sex. Among the negative qualities that put a woman on her guard, as noted in The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony, were:

“Keeps irregular hours

His studies do not form the subject of his conversation, as bearing on his future prospects

Shows disrespect for any age

Laughs at things sacred

Absents himself from regular attendance at church

Shows an inclination to expensive pleasures, or to low and vulgar amusements

Betrays a desire for enjoyments beyond his means or reach

Makes his dress a study

Betrays a continuous frivolity of mind.”

Etiquette manuals were replete with warnings to young ladies to beware being dazzled by “morally depraved” men or, as stated in Advice to Young Ladies:

“A young lady should be careful that brilliant qualities of mind, a cultivated taste, and superior conversational powers, do not overcome her virtuous repugnance to base principles and a depraved life.”

The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony also provided guidelines for gentlemen as they waded into the murky waters of courtship. A woman who was kind, patient, benevolent, peaceful, and charitable; and who enjoyed home-centered pleasures, was worth pursuing. But a gentleman should “retire speedily but politely” from a woman with any of the following traits:

“Has the heartless buzzing of a flirt

Gives smiles to all and a heart to none

An uneven temper

Is fond of dress, and eager for admiration

Is ecstatic in trifles and nonsense, and frivolity

Is weak in her duties

Is petulant, saucy, or insolent

If the holiness of religion does not hover like a sanctifying dove ever over her head

Is prideful, boasting, vane, sharp rather than quiet

Gaudy”

When choosing to cast his eye upon a young lady with views toward matrimony, a gentleman needed to be mindful of the following:

“You do not catch us by mere beauteous look,

Tis but the bait, floating without the hook.”