Julia Tredwell Takes the “Water-Cure”

by Ann Haddad

Julia Eliza Tredwell (pictured at right), Seabury and Eliza’s sixth child, was born on May 16, 1833. She was two years old when her father purchased the house on East Fourth Street that would be Julia’s home for the rest of her life. Many books in the Tredwell Book Collection bear her name, including several on French language and grammar, natural history, poetry, and mathematics.

Julia Eliza Tredwell (pictured at right), Seabury and Eliza’s sixth child, was born on May 16, 1833. She was two years old when her father purchased the house on East Fourth Street that would be Julia’s home for the rest of her life. Many books in the Tredwell Book Collection bear her name, including several on French language and grammar, natural history, poetry, and mathematics.

Julia’s Mysterious Illness

In a letter in the museum’s archive, written in August of an unnamed year, Julia expressed her concerns about her health to her mother. She was a guest at the National Hotel in Richfield Springs, a popular spa resort town in upstate New York, where she apparently went to take the “water-cure” to recover from an illness.

“I have felt very much better the past week. They all say I have gained. I feel it, but by weight I only have gained two pounds. I took a bath and I felt stronger as soon as I came out … It is so lonesome to be separated that I feel as if I ought not to stay as long as I have, but I hope in so doing that I will quite gain my strength.”

An Ancient Health Remedy: Water

Although we do not know the nature of the illness that befell Julia that summer, it would certainly not have been unusual for her to seek treatment at a spa hotel that offered the “water-cure,” a 19th century health reform movement that employed the therapeutic use of water to revitalize health and treat disease. Also known as hydrotherapy, it has been practiced since ancient times, when Greeks, Romans, and other early civilizations employed water for medicinal purposes. The perceived therapeutic value of springs rich in minerals such as bromine and sulfur was thought to be attained by a combination of bathing and drinking the water. After waning in the Middle Ages, the popularity of this form of alternative medicine spread throughout Europe and eventually became a craze in the United States, in part as a reaction to the brutal practices of blood-letting, purging, blistering, and other medical treatments of the time, which often worsened the patient’s condition.

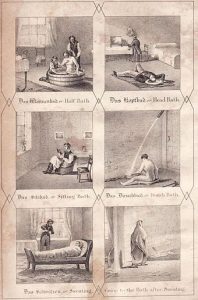

The “water-cure” involved various rituals, some less aggressive than others, such as submersion in hot or cold tubs of mineral-rich water for hours at a time; wrapping in cold sheets and then sweating; as well as ingestion of 1-2 liters of foul-tasting mineral water in one sitting. Cold water enema was also considered to be of therapeutic value in treating bowel inflammations and constipation. The “water-cure” was prescribed for the relief of many other ailments, especially gout and arthritis; it offered a gentler alternative to the violent medical therapies typically employed. Dietary remedies, including abstention from coffee, tea, salt, and alcohol, as well as meat and dairy products, were also prescribed.

“For the Invalid and Pleasure Seeker”: Water-Cure and Vacation in One!

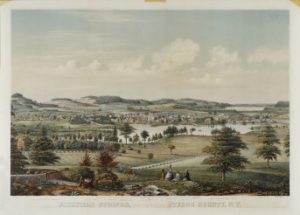

By the mid-19th century, the popularity of summer resort towns built around curative springs had soared, especially in New York State. The grand spa hotels typically featured hot and cold water therapy along with dietary and hygienic programs. Ever fearful of the summer cholera and other illnesses caused by the “miasma” that pervaded the air in New York City, those wealthy enough to escape eagerly adopted this fashionable practice, combining their quest for health with a desire for an elite vacation amidst splendid scenery. Among the most popular spa towns were Saratoga Springs, Ballston Spa, and Richfield Springs, which was celebrated for its sulfur water. Located about 65 miles west of Albany, Richfield Springs, where Julia stayed one August, began to draw visitors as early as the 1820s, after Dr. Horace Manley brought 25 patients to take the “water-cure” at his new sanitarium on the site of the Great White Sulphur Springs.

The Water-Cure for New Yorkers, Too

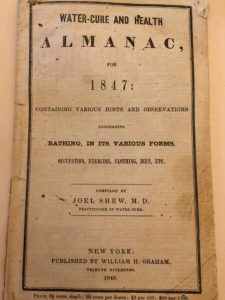

In 1843, Dr. Joel Shew (1816-1865) established a hydropathic treatment business in New York City, the first of its kind in America. He and his wife, Marie Louise Shew, ran the center out of their home on 4th Street, four blocks away from the Tredwell home. In 1845, Dr. Shew founded “The Water-Cure Journal and Herald of Reforms,” which promoted the principles and efficacy of the “water-cure.” Mrs. Shew, herself a staunch promoter of healthy living for women and children, wrote a popular treatise on the benefits of the water-cure, as well as proper diet and exercise, “Water-Cure for Ladies.”

By 1846, the Shews had relocated to 56 Bond Street, just a block from the Tredwells, where their Institution for the Practice of Water-Cure, was “situated in a very airy and pleasant part of up town, New York.” The Shews charged $1 to $2 per day for room and board, medical treatment, and advice, and focused their attention particularly on lung disorders, as “the air of New York is exceedingly bland and favorable for cases of the above-named kind.” The Tredwells may have known of the Shews’ water-cure business; they most likely would have been acquainted with and perhaps even subscribed to the Journal, as it was a very popular periodical of the time, acquiring 50,000 subscribers by 1850. As Dr. Shew stated in his Water-Cure and Health Almanac of 1847:

“…by the judicious use of cold water alone, the good effects of bleeding and blistering are most readily produced, without any of the bad effects, including the pain.”

Mineral Water in Central Park

Even New York City residents who did not have the means to escape the heat and humidity of their home town had access to therapeutic waters. In 1869 Central Park opened its own Mineral Water Pavilion north of the Sheep Meadow, which sold many varieties of spring water with desirable chemical properties thought to promote health and cure illness. Not to be outdone by the offerings of the lavish summer resorts outside of New York City, the Pavilion offered morning summer recitals as an entertainment for the water-ingesting masses. Due to the unprecedented demand for mineral water in the city, merchants in the spa towns took to bottling the mineral water and shipping it to the municipal markets. In the letter to her mother, Julia refers to a neighbor being able to obtain the mineral water from “Cozzens,” who is mentioned in an advertisement in The New York Times, May 16, 1861:

“Sulphur water from these celebrated Springs has been kept for sale, at F.S. Cozzens, number 23 Warren Street.”

Did Julia Recover?

By the turn of the century, with the discovery of germ theory and advances in drug therapy, and as the leisure class sought other forms of entertainment, the popularity of the resort spa towns and the “water-cure” declined. While we don’t know if the “water-cure” proved therapeutic for Julia, or if that was her only foray into a spa town for her health, it most likely did her no harm. She died in 1909 at her home on East 4th Street, at the age of 76.

Sources:

- Bailey, W.T. Richfield Springs and Vicinity. New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1874.

- Legan, Marshall Scott. Hydrotherapy, or the Water-Cure in Wrobel, Arthur, ed. Pseudoscience & Society in 19th-Century America. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1987.

- Miller, Tom. “The Lost Mineral Water Pavilion of Central Park.” Web blog post. Daytonian in Manhattan daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com. 14 August 2010. Web 20 April 2016.

- Shew, Joel, ed. Water-Cure and Health Almanac for 1847. New York: William H. Graham, 1846.