Ladies of Refinement: The Women Who Educated the Tredwell Daughters

by Ann Haddad

Six Tredwell Daughters to Educate!

As the daughters of a prosperous merchant, the six Tredwell girls were granted all the privileges of the elite class in which they were raised, including a private school education. From among the many girl’s schools in New York City, Seabury and Eliza chose two of the best for their daughters – Mrs. Okill’s and Mrs. Gibson’s. [For a discussion of private school education for boys, click here to read “Samuel Tredwell’s School Days,” September, 2017.]

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Mary Jay Okill owed a debt of gratitude to the Tredwell family. Mrs. Okill (1785-1859), was the headmistress of one of the most highly regarded female academies in New York City in the Antebellum era. Seabury and Eliza Tredwell, by entrusting her with the education of all six of their daughters over a period of at least 20 years, demonstrated support for Mrs. Okill’s system of education, at a time when the wealthy and elite families of the City could choose from among many similar private institutions. The decision by the Tredwells to send their daughters to Mrs. Okill’s likely influenced other wealthy families in their circle.

The Finishing Touch Plus Morality

In the first half of the 19th century, the aim of elite female education was to provide young ladies with the social graces and manners befitting their place in society, and to instill a basic knowledge of literature, classics, arithmetic, and geography. Several schools also included instruction in the religious and moral principles that would lead to the development of virtuous, charitable, and benevolent character. This approach, which Mary Okill outlined in detail in her first advertisement for her new academy in the Christian Journal, and Literary Register (1823), certainly appealed to parents such as Seabury and Eliza Tredwell, for it would essentially “finish” their daughters by preparing them for the most important roles within their sphere: those of wife and mother. As the advertisement states:

“… while every attention will be paid to the ordinary and ornamental branches of a finished female education, the department of religious instruction will receive particular care. Mrs. Okill … will devote her time to the superintendence of her school, and to the religious principles, morals, and manners of those young ladies who may be confided to her care.”

So Many Choices!

The single-gender “academy,” copied in style and substance from the British finishing school, was extremely popular among the wealthy of New York City in the early-mid 19th century. Such schools, which occupied rented houses run by a head teacher, typically offered opportunities for both day and boarding school students; the staff, who lived at the establishment, included other teachers, cooks, and domestic servants. Teacher training and curriculum was not standardized. With time and the increasingly progressive nature of female education, the homelike atmosphere gradually transitioned to larger, more structured female academies (also called seminaries), with formally trained teachers and rigorous curriculums. [For a detailed description of what the Tredwell girls would have experienced while students at Mrs. Okill’s, see Mary Knapp’s An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65 (2012)].

Mrs. Okill’s Tops the List

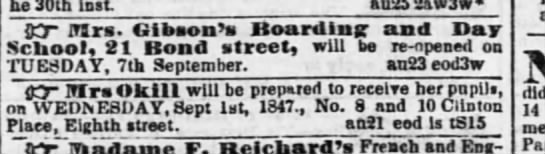

Competition for students must have been fierce among the women who ran the schools. Every year, beginning in late August and continuing through mid-September, advertisements for the schools, complete with names of notable individuals who were willing to provide endorsements, appeared in the daily newspapers. In New York As It Is (1833-1837), Mrs. Okill’s name is at the top of a list of 20 “Principal Female Seminaries” spread throughout the city. Ten years later, that number had grown significantly. In addition to Mrs. Okill’s, some of the other renowned female schools during this period, as mentioned by Catherine Elizabeth Havens (1839-1939), in her Diary of a Little Girl in Old New York (1919), were:

“Madame Chegaray’s, Madame Canda on Lafayette Place [both french schools], Mrs. Gibson on the east side of Union Square [more about her later], Miss Green’s on Fifth Avenue, just above Washington Square, and Spingler Institute on the west side of Union Square, just below Fifteenth Street.”

Influential Connections

When one considers that Mrs. Okill included the name of Reverend Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk (1791-1861) as a reference in her advertisements, it is understandable that Seabury Tredwell supported the school. Onderdonk was a relative of Seabury’s, and, as Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, a highly respected clergyman (until he wasn’t: stay tuned for a future post that will discuss his 1845 downfall). Other renowned citizens of New York, including Bishop Hobart, James Bleecker, and Peter A. Jay, also endorsed her school, which served to guarantee her cachet among the upper class.

Mrs. Okill Illegitimate … and a Divorcee?

Several circumstances of Mrs. Okill’s life, however, turn her pedigree on its head, notably her illegitimate birth and her divorce.

Mary Jay Okill was the daughter of Sir James Jay (1732-1815), oldest brother of John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Sir James, known primarily as the inventor of an invisible ink used by George Washington and his spies during the American Revolution, was also a physician and member of the New York State Senate; he was knighted by King George III for his fundraising efforts on behalf of Kings’ College.

According to an article in the Newsletter of the Bergen County Historical Society (2015-16), Sir James Jay never married Mary Jay’s mother, Anne Erwin (1750-1840), although they lived together in Springfield, New Jersey. A staunch advocate of a woman’s right to education, Miss Erwin refused to “honor and obey” Sir James, and therefore no marriage took place.

Mary Jay married John Okill, a merchant, on August 13, 1807, at Saint John’s Church on Varick Street. City Directories indicate that from 1807 through 1814, the couple lived with her father at various addresses on Greenwich Street and White Street. After Sir James’ death in 1815, neither Mary nor John Okill appear in the directories until 1819, when John Okill is listed as a broker on Wall Street. This entry remains unchanged until 1823, when he disappears entirely from the directories. The date and place of his death could not be determined.

In his will, probated in 1815, Sir James Jay stipulated that his daughter Mary’s inheritance, which included nearly 1,000 acres of land in what is now Closter, New Jersey, be put in trust “free of any control of her present husband, John O’Kill [sic].” According to the aforementioned article, Mary Okill divorced her husband in order to claim her inheritance. To earn a living, and perhaps influenced by her mother’s feminist beliefs, she opened a school for young ladies. Mary Okill is first listed in the 1823-4 City Directory as the proprietor of a “boarding school,” located at 43 Barclay Street. She remained at this location until 1838, when she moved to 8-10 Clinton Place (now 8th Street). She maintained her school until her death in 1859. Her establishment was always known as Mrs. Okill’s Academy.

What a Woman!

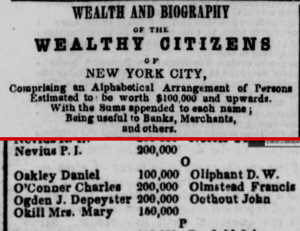

It is remarkable that, despite the social stigma associated with illegitimacy and divorce during the 19th century, Mary Okill was able to achieve such renown, especially among the privileged class, who valued family pedigree above all else. One wonders what shielded her from disgrace? Did her wealthy patrons know of her past, and decide to simply look the other way, due to the reputation of her uncle, John Jay? Or did she somehow manage to keep her background and divorce hidden from public scrutiny? In whatever manner she managed to maintain her reputation, her school was continuously celebrated as being run by “a lady of distinction,” and was undoubtedly a huge financial success. In an article in the New York Daily Herald (January 11, 1845), Mrs. Mary Okill is one of only a handful of women included in a list of the “wealthiest citizens” of New York City, with a net worth of $150,000. She joined such wealthy men as Adam Tredwell, Seabury’s brother, whose net worth was listed at $200,000.

The Tredwell family had an indirect connection to John Jay, which may have been a factor in their loyalty to Mary Okill. Reverend Samuel Nichols, Elizabeth Tredwell’s father-in-law, who married Elizabeth and Effingham in 1845, pronounced the eulogy at the Chief Justice’s funeral in 1829. Additionally, one of Effingham’s brothers, John Jay Nichols, was his namesake.

Co-Ed for the Children

Although it was known primarily as a female school, Mrs. Okill’s Academy also welcomed very young boys as students. Julia Lawrence Hasbrouck (1809-1873), who lived on Greenwich Street, enrolled her six-year-old son Louis and her five-year-old daughter Julia in Mrs. Okill’s Academy in 1843. She wrote her positive impressions of the school in her diary on November 30, 1843:

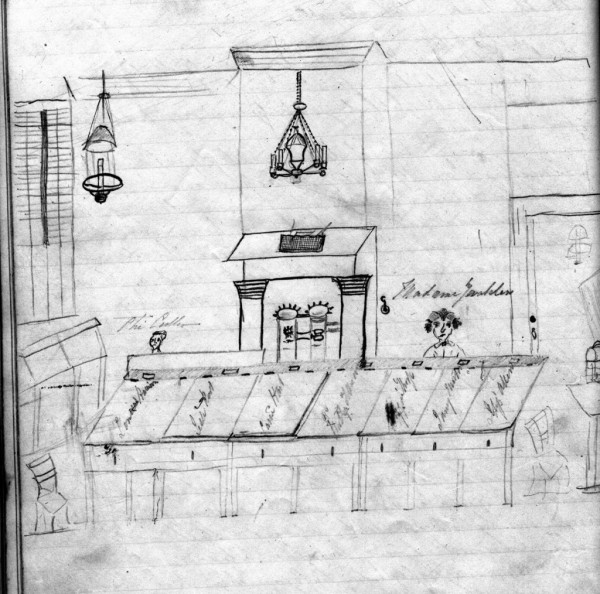

“The room was neat, comfortable, and well arranged. The little boys all looking happy, and merry. We went from there, to the little girls room, where I was equally pleased. The little creatures are not pinned down to their seats like prisoners, pale, and wearied; but were skipping around, combining study and amusement, the only safe method of instructing children.”

Although young Julia Hasbrouck attended Mrs. Okill’s at least through 1850, her brother Louis eventually joined another brother at an all-boys school. It is possible, then, that the Tredwell girls (and perhaps boys) attended Mrs. Okill’s from a much earlier age than was previously assumed.

Notable Students

In addition to the Tredwells, Mrs. Okill’s school attracted other families that made up the glitterati of New York society.

One of Mrs. Okill’s students was Eliza Hamilton Schuyler (1811-1863), the granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton. In 1825, when she was a 14-year-old student, Eliza was given a “prize book” from Mrs. Okill. In the Hamilton-Schuyler Family Papers at the University of Michigan, there are references to “Miss Okill’s ‘Testimonials’ for Eliza on that dainty embossed note paper …” and “While Eliza Hamilton was at Mrs. Okill’s School winning her encomiums …”

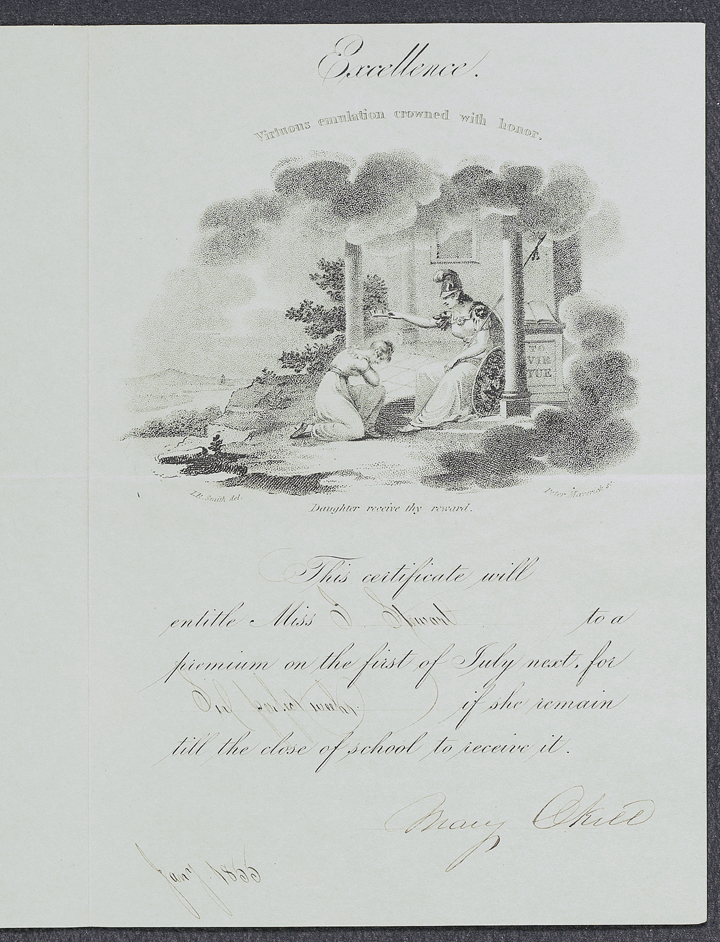

Another was Isabella Stewart (1840-1924), the daughter of a wealthy merchant, who would later marry John Lowell Gardner and become a famous art collector and philanthropist. From ages 5 to 15, while living with her family at 10 University Place, Isabella attended Mrs. Okill’s Academy. In 1855 she was awarded a Certificate of Excellence by Mrs. Okill, in return for a commitment to “remain till the close of school to receive it.” One year later, Isabella embarked on the Grand Tour of Europe with her parents and was enrolled in a French school to finish her education.

After Mary Okill’s death in 1859, the school closed, but her widowed daughter, Jane Swift, who had been a teacher at the school, continued to reside there. By May 1860, when the family moved to West Point, New York, the “very valuable property” on Clinton Place was up for sale. Like Mrs. Okill herself, the buildings were considered to be “of a superior character.”

Gertrude Tredwell, the Transfer Student

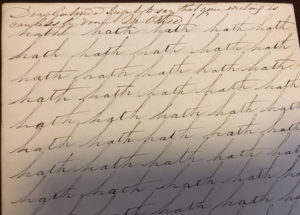

Among the copybooks belonging to the Tredwell girls in the Merchant’s House Museum archives, several belonged to Gertrude Tredwell. One, dated from December 16,1853, through February 13, 1854, (when Gertrude was 13 years old), indicates that Gertrude attended Mrs. Okill’s School, for at the end of a composition, a withering comment appears, written by the headmistress herself:

“Dear Gertrude, I regret to say that your writing is carelessly done. M. Okill”

Other copybooks of Gertrude’s, which date to 1858, do not contain any teacher’s notes. The Museum’s copy of Seabury Tredwell’s ledger book includes entries for payment of bills for “Gertrude’s tuition at Mrs. Gibson’s,” dating from 1855 and 1858 (tuition at the private academies averaged approximately $70 per year). We don’t know the reason for Gertrude’s departure from Mrs. Okill’s School. Whatever the reason for the transfer, Gertrude finished her education at the age of 18, under the tutelage of Mrs. Gibson.

Mrs. Gibson

In 1832, nearly ten years after Mrs. Okill opened her female academy, Mrs. Agnes Mason Gibson (1787-1872), from Edinburgh, Scotland, established her own school, assisted by three of her daughters. Originally located on Broome Street and operating as a day school, it was advertised on April 10, 1832, in the Evening Post:

“The Misses Gibson, having been educated under the first masters, are prepared to give instruction in all the branches of a useful and ornamental female education. Pupils will be received for French, Italian, Music, or Drawing, who may not wish to enter for other branches. Instructions upon the pianoforte and guitar will also be given in private homes. [Guitar instruction was not unusual. Christian Frederick Martin, the famous guitar maker who established his shop in New York City in 1833, sold several guitars to Mrs. Okill]. A class for conversation and composition in French will be opened on Saturdays, for young ladies who have made proficiency in the language.”

A Resounding Success

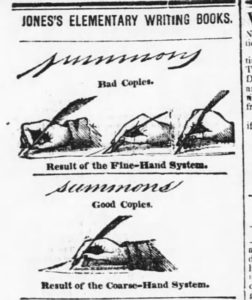

Two months later, Mrs. Gibson “expanded her plan” to include boarding students. Within a few years, her school achieved a remarkable degree of popularity; Mrs. Gibson became an influential educator in New York City. Manufacturers of school supplies sought her out for endorsements. In September 1838, an advertisement in the Evening Post featured Mrs. Gibson’s endorsement of Jones’s Elementary Writing Books. Mrs. Gibson stressed the importance of having children instructed in “large hand exercises:”

“I attribute the defects in the hand writing of young ladies to injudicious teaching in giving fine-hand exercises to write, before any foundation or command of the pen is acquired in large characters.”

“An Excellent Seminary”

As the school expanded it relocated several times, from Broome Street to Broadway to 21 Bond Street (just two blocks from the Merchant’s House), where in 1845, Mrs. Gibson gave an exhibition of her students’ work, which was lauded in the New-York Tribune. The school was referred to as “an excellent seminary – one of the best in the city for the instruction of young ladies.” The article goes on to say:

“We were particularly struck with the taste and judgment displayed in the elocutionary exercises. The French dialogues were given in a sprightly and graceful manner, and the vocal music was charming. We traced throughout the evening the workings of an intelligent, kindly, and well sustained course of instruction.”

The New York Post also covered Mrs. Gibson’s May Day Festival in May 1849:

“Of note were the performances of charades, in which the ingenuity and invention of the youthful scholars were exhibited. Many of the former pupils were present. It is charming thus to see wisdom’s ways made ways of pleasantness.”

The Dear Scottish Daughters

One of Mrs. Gibson’s students was Julia Cullen Bryant (1831-1907), daughter of poet and New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), who attended the school in 1844 at age 13. The family must have formed a strong attachment to Mrs. Gibson and her daughters, for William Bryant maintained a correspondence with his daughter’s teachers, Christianna Gibson in particular, until his death.

The Final Move

In 1851, Mrs. Gibson moved again, from 21 Bond Street to larger quarters at 38 Union Place, to accommodate her growing enrollment. Gertrude attended the school at this location, which was a short walk from her home on Fourth Street. The school operated at this location at least until 1861; eventually, Mrs. Gibson returned to Scotland with her daughters, where she died in 1872.

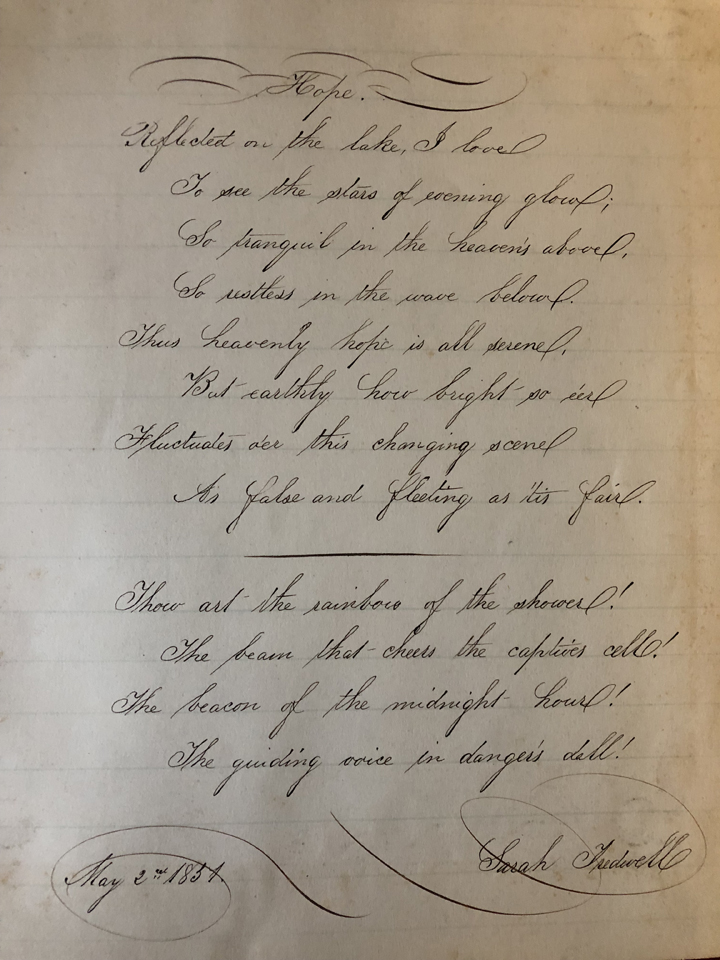

“An Annoyance and a Pleasure”

Despite the number of filled copybooks belonging to the Tredwell girls, all but one lacked any clues about the young women’s sentiments toward their schools. Only 18-year-old Sarah was brave enough to venture an opinion about her school years and the education she received. In a composition entitled “To a Dear Friend,” dated May 18, 1853, she expressed her ambivalence about her experiences and the end of her school days:

“Some say our school days are the most happy. I believe it to be true though there are certainly many things pertaining to school which are of a very perplexing nature. I will leave school the first of July, when I am to leave forever that place which I have frequented so many years and which has been to me both an annoyance and a pleasure. To those to whom I have grown and with whom I have shared the troubles of a school day life and to whom I must ever feel attached I must bid adieu but I hope not forever.”

Sources:

- Brown, Henry Collins. Valentine’s Manuel of Old New York, new series, no. 2. New York: Valentine Co., 1917.

- Bryant, William Cullen and Thomas G. Voss. The Letters of William Cullen Bryant: Volume IV, 1858-1864. New York: Fordham University Press, 1993.

- Christian Journal, and Literary Register, Volume 7-8, May, 1823. https://books.google.com. Accessed 9/9/18.

- Colony Club. Catalogue Exhibition “Old New York” Relics Documents and Souvenirs. New York: Colony Club, 1917.

- Evening Post. 25 August, 1824, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/5/18.

- Evening Post. 10 April, 1832, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 13 June, 1832, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 10 September, 1833, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- Evening Post. 22 August, 1834, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 13 January 1838, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- Evening Post. 1 September, 1838, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 30 August, 1847, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Evening Post. 3 May, 1849, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Evening Post. 14 April, 1851, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Gura, Peter F. C.F. Martin & His Guitars, 1796-1873. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Hamilton-Schuyler Family Papers 1820-1924, William L. Clements Library Manuscript Division, University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu. Email 9/6/18.

-

Hayley, Ann, Robert Campbell et al. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: Daring by Design. New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2014.

- Knapp, Mary L. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- Leslie’s History of the Greater New York. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York register, and city directory. New York: David Longworth, [multiple years]. Reference, New York Historical Society.

- Madigan, Jennifer C. “The Education of Girls and Women in the United States: A Historical Perspective.” Advances in Gender and Education, 1 (2009), 11-13. www.mcrcad.org. Accessed 9/2/18.

- Manhattan, New York City, New York Directory: 1829-1830;1839-1840. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- Merchants House Museum Archives. Seabury Tredwell’s Ledger Book [copy], 1855-1865.

- Merchant’s House Museum Archives. Composition Book of Sarah Tredwell, May 18, 1853. 2002.4601.89.

- Merchants House Museum Archives. Penmanship book of Gertrude Tredwell, Dec. 16th, 1853 – Feb. 13th, 1854. 2002.4602.29.

- New York County, New York, Wills and Probates, 1658-1880. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- New York Evening Post. 22 Dec 1859. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- New York Evening Post. 27 June 1839. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- New York Daily Herald. 11 January 1845, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- New York Daily Herald. 26 February, 1856, p. 5. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- New York Herald. 9 August, 1922, p. 11. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/22/18.

- New York Times. 20 September, 1859, p. 6. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/5/18.

- New York Times. 15 May, 1860, p. 6. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- New-York Tribune. 30 December, 1845, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Stessin, Susan. The Diaries of Julia Lawrence Hasbrouck. www.frommypenandpower.wordpress.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- Williams, Edwin, ed. New York As It Is, [1833-1837]. New York: J. Disturnell, 1833-1837.

- Wilson, James Grant, ed. The Memorial History of the City of New-York, Vol. III. New York: New-York History Company, 1893. https://books.google.com. Accessed 9/5/18.

- Wright, Kevin. “Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Tenafly.” In Bergen’s Attic: Newsletter of the Bergen County Historical Society. Fall/Winter, 2015-2016, p. 7-14. www.bergencountyhistory.org. Accessed 9/11/18.

Samuel Tredwell’s School Days

by Ann Haddad

Back-to-School!

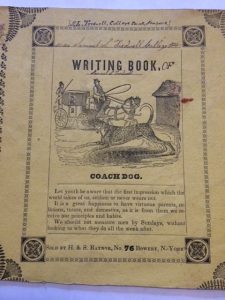

September was a busy month for Eliza Tredwell. After spending summer vacation at the family farm in Rumson, New Jersey, this mother of seven children (ranging in age from 3 to 17), returned to the city and faced the task of back-to-school shopping. Like today’s mothers who endure long lines at Staples, Mrs. Tredwell likely dealt with the crowds at such shops as H. & S. Raynor, on the Bowery, and C. Shepard & Co., on Fulton Street, to buy ledgers, notebooks, and writing instruments for her children’s school work. She also may have patronized clothing stores such as Brooks Brothers or Lord and Taylor’s, on Catherine Street, to outfit the children for the school year.

Boarding School for Samuel

What made 1838 different was that her 11-year-old son, Samuel Lenox (1827-1917), was enrolled in boarding school for the first time. Leaving home at a young age to attend school was not unusual, for in the early 19th century, most schools of higher education enrolled students between the ages of 12 and 15.

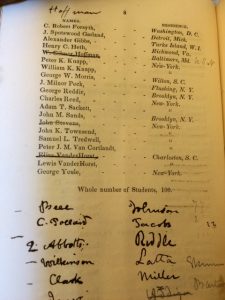

On October 1, 1838, Samuel began his first year at St. Paul’s College and Grammar School, located over six miles from Manhattan in College Point, on 100 acres along the shore of Long Island Sound (now part of Queens). In the Introductory Class, he counted among his 31 classmates members of the Van Cortlandt, Morris, Jones, and other distinguished New York families.

As he would be living away from home for the entire school year, Samuel’s shopping list was longer than those of his sisters, who attended day schools. As stipulated by St. Paul’s, his necessities included sufficient clothing, at least half a dozen towels, hair brushes, and other toiletries. On Sundays and religious feast days he was required to wear a uniform dress suit:

“a single breasted round jacket, with a rolling collar and black worsted buttons,

of dark blue cloth, pantaloons, and a black silk vest.”

In addition, Samuel needed a bible and a prayer book, both stamped with his name.

The Respected Founder

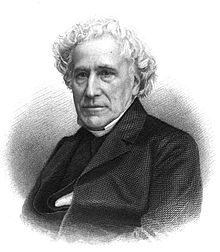

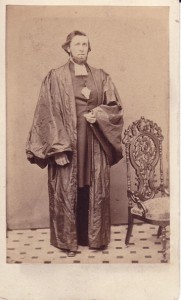

Founded in 1835 by Dr. William Augustus Muhlenberg (1796-1877), St Paul’s College and Grammar School had as its objective “the intellectual and moral education of Boys, in accordance with the principles of the Protestant Episcopal Church.” An early “Church-School” scholastic model that combined a classical education with the tenets of Christianity, it sought to provide both academic rigor and moral lessons, while emphasizing the familial nature of the school.

Daily chapel was an important part of the school day, as was the study of Scripture; from these practices standards were set that would lead to the development of Christian character. Dr. Muhlenberg, upon being asked, “What kind of boys do you want?” replied:

“Give us such boys as have been blessed with the instructions of a pious mother.”

.

The Cost of an Education

Seabury Tredwell paid a yearly tuition of $300 for his son’s education at St. Paul’s. The school year ran from the first week of October through the first week of August. The cost included all classes (except for music and drawing), and room and board. After paying an optional fee of $7 per year for the care of a physician who resided at the school, it must have reassured the Tredwells to learn that:

“It is a remarkable fact that since its opening…not a pupil has died, or contracted a fatal illness on the premises.”

On to “College”

After spending three years in the Grammar School, where he studied mathematics, English, and writing, Samuel matriculated at age 14 to the College. When his use of the term “College” was called into question, Dr. Muhlenberg, responded:

“Whenever our senior boys know less of Latin, Greek, or Mathematics,

than the majority of the A.B.s in the US, we shall begin to think

there is some arrogance in calling our school St. Paul’s College.”

The curriculum, taught by distinguished professors and clergymen (among whom was Reverend Samuel Seabury, the son of Seabury Tredwell’s namesake), included Greek and Latin classics, mathematics, Scripture studies, French and English literature; and, (unusual for the time), physics, geology, chemistry, and anatomy. The skills of elocution and recitation were also highly valued and emphasized in the daily studies. Corporal punishment was forbidden; monthly reports of the students’ progress, including marks for “disorder,” were sent home to parents. Viewed as a superb and progressive school in its time, St. Paul’s saw many of its graduates go on to esteemed colleges.

St. Paul’s also offered a “Mercantile Studies” program, in which students took courses such as Merchandise and Commerce, Laws of Trade, Statistical and Commercial Geography, and Bookkeeping. For reasons unknown to us, Samuel did not choose this program.

All Work and No Play Makes Samuel a Dull Boy

The daily schedule at St. Paul’s was long and regimented, but three hours of every day were set aside for recreation. Saturdays were devoted to play and to the welcoming of visitors.

Situated on an idyllic peninsula, the campus of St. Paul’s was ideally situated for outdoor sports. The boys enjoyed rowing and swimming in a cove immediately in front of the school, as well as ice skating, gardening, and riding. Several religious festival days, including the Epiphany and St. Paul’s Day, were celebrated with the cancellation of classes, and with “huge” cakes and other sweets provided by parents.

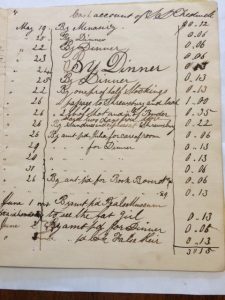

Samuel’s 1843 cash book paints an amusing picture of the school life and antics of a 16-year-old boy. Among his purchases that year were boots, an accordion, fishing tackle, a lock of “false hair,” and entry to “Peal’s Museum to see the fat girl.” Samuel must have broken the school rules when he paid 31 cents for a dog named Nip, only to pay Charly 6 cents to take care of Nip for one day! And, on at least one occasion, he broke the rule that forbade visits home to parents, when he traveled by boat to Rumson and back.

On the last few pages of the same cash book may be found Samuel’s awkward attempts at romantic poetry, along with this line scrawled in the margin:

“Poetry is the way to the heart of a woman.”

Life after St. Paul’s

Due to lack of sufficient endowment funds, the New York State legislature repeatedly denied St. Paul’s College a collegiate charter, which in effect forbade the school from granting degrees. In 1846, after 11 years of service to the school, Dr. Muhlenberg resigned his position to become rector of the Church of the Holy Communion in New York City. Despite their best efforts, the lack of funds forced the administrators to close the school in 1850. The buildings and land were sold to a private developer.

We don’t know what Samuel thought of the education he received at St. Paul’s College. Did he find the experience memorable? How did it impact his life and the choices he made? At least one former student seemed to recall the school with fondness. Thomas Kelah Wharton (1814-1862), wrote in his diary many years later:

“I passed some 8 years of my life in the pleasant seclusion of scholastic

pursuits. What a change! The revered Professors gone! The Muses’ haunt,

the marble porch where Wisdom went to talk with Socrates or Tully, hears

no more, save the hoarse dissonance of jarring wheels.”

Sometime after 1843, Samuel Tredwell left the school. According to city directories, by 1845, at age 18, he was back home on 4th Street, working as a commercial merchant on Front Street. On December 13 of that year, he began a four-year law clerkship with his brother-in-law, Effingham Nichols, an attorney in New York City, while simultaneously continuing as a commercial merchant and, in 1847, as a distiller on Water Street. The law must not have been Samuel’s cup of tea, for in December 1848, he took over his cousin’s crockery business at 195 Pearl Street, an enterprise he owned until 1854. Samuel had followed in his father’s footsteps after all, literally walking down the same street, to become a merchant.

Sources

- An Account of the Grammar School, or Junior Department, of St. Paul’s College. New York: F.C. Gutierrez, 1842. New York Historical Society Library.

- Ayres, Anne. The Life and Work of William Augustus Muhlenberg. New York: T. Whittaker, 1889. Accessed September 8, 2016. www.anglicanhistory.org.

- Cash Book, S.L.Tredwell, College Point, N.Y., 1843. Merchant’s House Museum Archives. 2002.4602.27 Box 3.

- Catalogue of the professors, instructors, and students of St. Paul’s College and Grammar School, for the session of 1839-40; together with the act of incorporation, constitution of the college, board of visitors, course of studies, discipline, &c. and observations addressed to parents intending to place their sons in the institution. College Point, N.Y. : [s.n.], 1840. New York Historical Society Library.

- Doggett’s New-York City Directory. New York: John Doggett, Jr. 1846-1854. New York Historical Society Library.

- Hunt, Thomas C. and James C. Carper, eds. The Praeger Handbook of Faith-Based Schools in the United States, K-12, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2012.

- Journal of Saint Paul’s College, Feb., 1844, Vol 1, no. 1, College Point, NY: Charles R. Lincoln, 1844. New York Historical Society Library.

- Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “College Point in 1839” New York Public Library Digital Collections.1854. Accessed September 7, 2016. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ecfc2630-e5fd-0132-978d-58d385a7bbd0.

- Writing Book, S.L. Tredwell, College Point, NY, 1843. Merchant’s House Museum Archives. 2002.4602.28 Box 3.