Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part 3 – Man of Opportunity

by Ann Haddad

An Astute Businessman

George Chapman, who founded the Merchant’s House Museum in 1936, named it “The Old Merchant’s House” as a tribute to the early 19th century merchants who were known as the old merchants, among them Seabury Tredwell, who built New York City into the “commercial emporium of America” (as was said in the 19th century). However, Seabury Tredwell’s occupation certainly did not define him. Although he was a New York City hardware merchant (and a very successful one: see my post Seabury Tredwell, Part 2 – The Merchant Years), he did not confine his business interests to his Pearl Street warehouse and to life on the seaport. Rather, Seabury held a progressive view of the city and the nation’s capacity for growth; beginning in 1816, he began to invest in real estate, an interest that would continue until his death. As his career flourished, he purchased properties in Manhattan and Brooklyn, as well as further afield in North Carolina and Michigan. Seabury also kept abreast of the country’s industrial development, investing in the burgeoning railroad and coal gas companies.

New York on a Grid

Relatively early in his career (and just one year after taking on his nephew as a business partner), Seabury Tredwell started investing in the New York City real estate market. No doubt he was influenced and guided by two of his older brothers, Adam and John, who had moved to the city several years before Seabury, and who, by the first decade of the 19th century, owned extensive real estate in New York City and Brooklyn City. Seabury’s real estate investing involved him in one of the most important chapters of New York City history: the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, which called for the reorganization of Manhattan’s haphazard landscape into streets and avenues in a rectilinear grid pattern. Seabury’s first real estate purchase indicates that he was very likely aware of the Commissioners’ Plan. Probably eager to profit from the city’s anticipated growth patterns, in May 1816, prior to his marriage and while living in a boarding house, Seabury purchased a substantial three-lot parcel on the northwest corner of what is now 12th Street and Broadway, for $1,860.

The City Pays

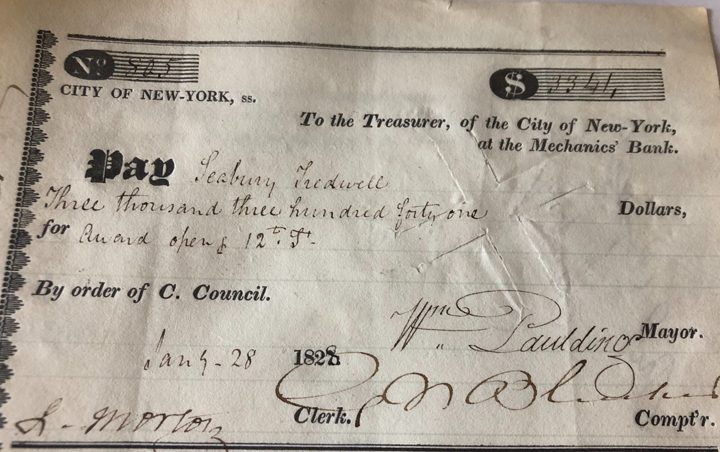

In 1826, ten years after Seabury purchased the property, New York City was preparing to open 12th Street; the first step of the process was to compensate all the property owners whose land would be claimed and used. According to the Minutes of the Common Council, on January 28, 1828, the city paid Seabury $3,341 for one lot of his property that was consumed by the grid. Nine other property owners also received payment.

Harlem Land

In December 1828, Seabury sold one of the remaining lots on 12th Street and Broadway to Michael Floy for $800, in exchange for 4 lots on 128th Street and 4th Avenue, in Central Harlem. Floy, a noted horticulturist, likely wanted the land to add to his already existing greenhouse south of what is now Union Square. The land in Harlem was a developing area, ideal for real estate speculation. Further research is required to determine if and how Seabury built on and profited from the Harlem investment.

A Wise Investment

Seabury sold the last lot on the property on 12th Street in February 1833 for $1,500. Seabury gained usable land in Harlem and realized a total profit of $5,641 from his original investment of $1,860.

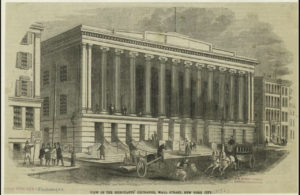

The New York Merchant’s Exchange

In addition to his personal real estate dealings, Seabury bid at auction for some of his properties at the New York Merchant’s Exchange, located at 55 Wall Street. Built in 1836-42, it replaced the original Exchange, which was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1835. The Exchange housed a post office, banks, and the Chamber of Commerce, as well as rooms for auction sales of real estate and stocks, which was at a fever pitch as the city growth pushed northward, and housing was in great demand to accommodate the exploding population.

According to the records of New York Merchant’s Exchange of July 17, 1856, Seabury purchased at auction a lot on the southwest corner of 8th Avenue and 53rd Street, for $4,050.

Seabury Bets on Brooklyn

When Seabury ventured into the frenzied Brooklyn real estate market in the mid-19th century, Brooklyn was the third largest city in America (it didn’t merge with New York City until 1898), and soon to become one of America’s major industrial centers, due to its location on the East River, which allowed for convenient transportation of materials and manufactured goods. Beginning in 1814, regular steam ferry service between Fulton Street in Brooklyn and Beekman Slip (now Fulton Street) in Manhattan, made it easy for affluent families who had moved to Brooklyn, as well as workers with jobs in the city, to commute back and forth.

.

.

Before It Was DUMBO

Seabury no doubt was aware of Brooklyn’s changing character and landscape when he acquired his first piece of Brooklyn property in March 1852, when he purchased, from the estate of his brother John, four plots on Fulton and Pearl Streets in the Second Ward, for $12,875. This area, located along the East River waterfront, is now known as the DUMBO Historic District (an area now bounded roughly by the Brooklyn Bridge, the East River, York, and Navy Streets). Although this area was one of the first residential-use sections of Brooklyn, by 1852 it was well on its way to becoming a major manufacturing center, with factories, foundries, and warehouses vying for space with two and three-story residential houses. Two ferry lines, one right at the foot of Front Street, made regular trips to and from New York City.

In 1853, Seabury sold this property for $15,500. In one and a half years, he made a profit of $3,500.

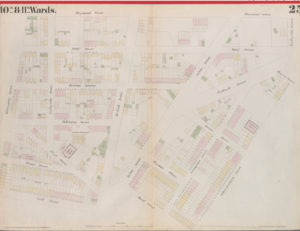

… and Fort Greene

In 1858 and 1859, Seabury added to his Brooklyn holdings with the purchase of nine lots, some with buildings, on Fulton Avenue, Raymond Street, and Navy Street, in the 11th Ward (now the Downtown Brooklyn/Fort Greene area), for $12,000. The property was advertised in the Evening Post in 1850 as being “located in the most desirable part of Brooklyn, being in the immediate vicinity of Washington Park, which is now being regulated and graded.” He immediately sold two of the lots for $4,600. In 1863, he sold four of the lots for $15,500, making a profit on land he had owned for only four years.

With the growth of middle-class residential districts, including Fort Greene, house construction in Brooklyn skyrocketed. Row houses appeared almost overnight on the quiet streets, and became ideal homes for professionals who commuted to their New York City businesses. According to Seabury’s personal ledger, he spent a great deal of money building on his Brooklyn properties. Between July and October 1863, for example, he paid John P. Seeley (a “master builder,” according to the 1860 Federal Census) $9,370, most likely for house construction. Seabury also paid $102.31 to have a sidewalk laid on his property on Raymond Street.

The Good Son-in-Law

Effingham Nichols, an attorney and the husband of Seabury’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth, must have been influential in Seabury’s decision to invest in Brooklyn real estate. He lived in Fort Greene with his wife and daughter, Lillie, from 1859 to 1864, and had begun to buy property there in 1851; by 1859 he owned at least seven properties in the neighborhood. (See my post of April 2017, “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing”). In addition, one of his brothers, William B. Nichols, owned houses near Seabury’s property on Fulton Avenue and Raymond Street. Effingham may have collected rents for Seabury, and may even have acted as an agent for him, buying and selling properties at his discretion. Records in Seabury’s personal ledger indicate that Seabury provided Effingham with funds to repair the Fulton/Raymond Street property. In 1863, for example, he gave Effingham $63.84 for sewer work.

In 1863, Seabury made what may have been his last purchase of Brooklyn real estate, bidding at auction for another parcel of land in Fort Greene, paying $4,400. The Land Conveyance Records Index for Kings County indicate that Seabury purchased at least three other properties in Brooklyn; the details of these purchases could not be determined because the conveyance records are missing.

Seabury the Landlord

Seabury also collected rents on some of his properties. In 1862, he rented three buildings on Fulton Avenue to Mary Louise Tredwell (a distant cousin) for $1,200/year. Seabury’s personal ledger indicates that in 1852 he was collecting rent of $1,000/year on a factory on Front Street, and $212.50/year for a Pearl Street property.

Seabury also engaged in seller financing, wherein he financed purchases of his property to individuals, rather than have them obtain a bank mortgage. In his personal ledger, he listed several individuals to whom he sold property, such as John and William Healy, John Rupp, and John David, and the amounts of the mortgages he granted.

Ventures Further Afield

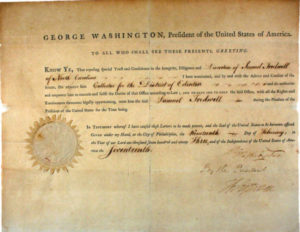

Records show that Seabury also invested in commercial property with his partners for their business. Seabury and his nephews likely decided to invest in real estate in North Carolina due to their business dealings there and their familiarity with the state. Seabury’s eldest brother, Samuel Tredwell (1763-1827), had been a prestigious figure in North Carolina after the Revolutionary War. In 1785, Samuel moved to Edenton, North Carolina, whose vital port was the second largest in the state. In 1793, he was appointed Collector of the Port of Edenton by President Washington, a position he held until his death. He also served as State Commissioner of North Carolina in 1818.

In 1835, Tredwell, Kissam & Company purchased 13,000 acres of North Carolina swampland from Charles Johnson for the purpose of harvesting lumber to make shingles. A North Carolina Supreme Court case in June 1840 involved a lawsuit brought against a trespasser who was using the land illegally. At this time it is unknown when and to whom Seabury sold the land.

In the Transactions of the Supreme Court of the Territory of Michigan, 1825-1836, there is a record of a court case involving Tredwell, Kissam & Company in a lawsuit against three men, Isaac Otis, George Walker, and John Hale. The nature of the suit is unknown.

The Children Benefit

A portion of the original property on Fulton Avenue and Raymond Street in Brooklyn was still under Seabury’s name upon his death in 1865, and became part of his estate. His children benefited from Seabury’s real estate savvy. In 1902, Samuel Lennox, his younger son, who had purchased the Fulton Avenue property from his father’s estate some years earlier, sold it for $40,200. The property was described in a February 1902 advertisement in the Brooklyn Eagle as “being a very valuable plot with three two story and cellar brick buildings thereon, with 5 stores therein.”

Seabury’s Investment Portfolio

It is unclear when Seabury set about building an investment portfolio, but by his death in 1865 he had amassed enough stock to significantly cushion his family’s inheritance. Getting in on the ground floor of both the steam engine and lighting revolutions taking place in New York City and elsewhere, he invested heavily in various railroad stock (including the New York and Erie Line, the Hudson Line, Chicago and Rock Island lines, and Hartford and New Haven lines) and in gas lighting. Seabury may have consulted his friends and former colleagues in the business world for advice; he also may have looked to his sons-in-law Effingham Nichols and Charles Richards for guidance in choosing his investments.

The New York and Erie Railroad Line

Seabury Tredwell was an early investor – and possibly one of the original investors – in the New York and Erie Line, a railroad that linked Erie Canal towns directly to New York City, allowing for faster transportation of lumber and agricultural goods. Leading merchants of the day, as well as land investors and bankers, were granted the charter in 1832, creating a railroad line that ran west from the Hudson River in Piermont, New York, to Dunkirk on Lake Erie. This proved to be a risky investment through the years, however; the railroad went bankrupt several times, and became known as “the scarlet woman of Wall Street,” due to the financial shenanigans of men like Jay Gould and Cornelius Vanderbilt, who vied for control of the railroad and manipulated the company holdings to their own advantage.

Take the Hudson River Line

The Hudson River Line was another of Seabury’s investments. In 1846, 11 years after Seabury sold his business, the Hudson River Line was chartered. This commuter line initially ran from Chambers and Hudson Streets in lower Manhattan up the West Side via horse cars (steam trains were not permitted below 30th Street) to a depot at 32nd Street, where the horses were exchanged for steam engines, then along the east side of the Hudson River, to Peekskill. By 1851 it had been extended to Poughkeepsie, which remains its terminus. Through a connection with the Troy and Greenbush Railroad, it provided a link between Albany and lower Manhattan, a trip of less than four hours. A similar journey by steamboat took over seven hours! One imagines that the growth of the railroad industry (with its speed, efficiency, and convenience) and its revolutionary impact on 19th century life was not lost on Seabury, who, like everyone else, had previously relied on the comparatively snail-paced omnibuses, ferries, and coaches.

New York Gas Light Company

Seabury’s personal ledger indicates that he owned 133 shares of stock in the New York Gas Light Company, the first coal gas company in New York, founded in 1823. One wonders if he was one of the original investors in the company, which first focused on street lighting, servicing Manhattan south of Canal Street. Ultimately six gas companies supplied gas for illumination and later, for heating and cooking. The competition for customers was so fierce in the growing city, that workers from different companies would do battle in the streets over the installation of gas mains; known as “gas house gangs.” In 1884, the companies merged to form Consolidated Gas Company (now known as Con-Edison).

More than a Merchant

Now that Seabury’s varied business interests have come to light, and we see the extent to which he ventured into unchartered investments, it is clear the title “merchant” doesn’t embrace all that Seabury was in the business world of the 19th century. Seabury Tredwell, along with many of his peers in the merchant class, were men of opportunity who shaped the economic future of New York City. Perhaps we should consider renaming the Merchant’s House — the “Investor’s House”? The “Risk-Taker’s House”? What do you think?

Sources:

- Blume, William Wirt, ed. Transactions of the Supreme Court of the Territory of Michigan 1825-1836, Volume II. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1940. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 5/29/19.

- Bristed, Charles A. The Upper Ten Thousand: Sketches of American Society. New York: Stringer and Townsend, 1852. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 6/5/19.

- Brooklyn Citizen. April 2, 1902, p. 9. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 5/3/19.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 22, 1902, p. 15. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 5/3/19.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Conveyances, 1724-. New York Land Records, 1630-1975. Images. familysearch.org.

- “Erie Railroad Company.” Encyclopedia Britannica. www.britannica.com. Accessed 6/3/19.

- Evening Post. October 5, 1850, pg. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 5/22/19.

- “History of Con Edison.” American Oil & Gas Historical Society. www.aoghs.org. Accessed 6/3/19.

- Koeppel, Gerard. City on a Grid: How New York Became New York. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2015.

- Lockwood, Charles. Manhattan Moves Uptown: An Illustrated History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1976.

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. DUMBO Historic District Designation Report. December 18, 2007. www.neighborhoodpreservation.org. Accessed 5/21/19.

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Fort Greene Historic District Designation Report. September 26, 1978. www.home2.nyc.gov. Accessed 5/22/19.

- New York Daily Herald, March 11, 1865, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/9/19.

- North Carolina. Supreme Court. North Carolina Reports: Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of North Carolina, [v 023, June Term 1840-June Term 1841]. State Library of North Carolina. www.digital.ncdcr.gov. Accessed 5/29/19.

- Notes from Seabury Tredwell’s Personal Ledger Book. Merchant’s House Museum Archives.