The Man That Got Away: Gertrude’s Lost Sweetheart

by Ann Haddad

An Abundance of Daughters

By anyone’s measure in antebellum New York City, the Tredwell daughters would have been viewed as highly desirable marriage prospects. As the children of Seabury Tredwell, a wealthy merchant with a fine home in the elite Bond Street neighborhood, they stood to inherit a portion of their father’s estimable worth. They counted among their social circle other members of the New York City upper class, and would have mingled with many eligible young men at the frequent soirées held at one another’s homes, or at other socially acceptable venues.

Party Girls

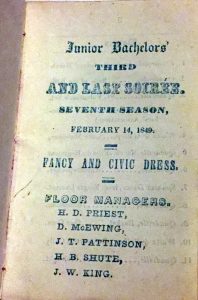

The Museum archives contain several items, including dance cards and playbills, that provide a glimpse of the Tredwell daughters’ social whirl. One is a silver Valentine’s Day dance card from the “Junior Bachelor’s Third and Last Soirée,” dated February 14, 1849. The lovely dresses in the Museum’s collection that belonged to the sisters indicate that they had the means and the sophisticated taste to keep up with fashion trends.

A Gentleman Caller

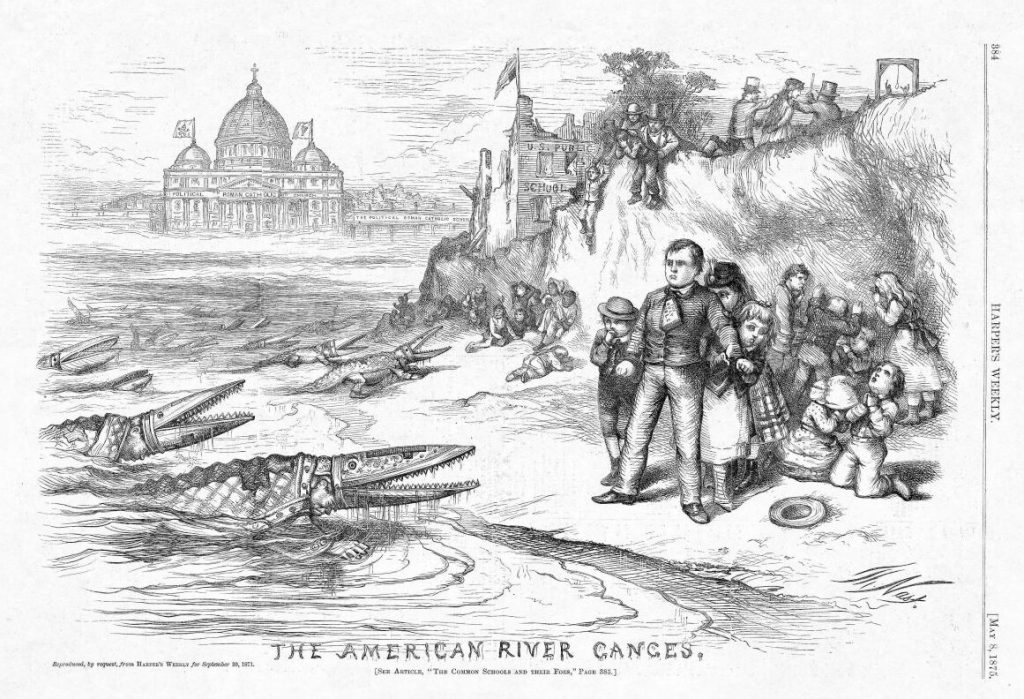

Gertrude Ellsworth Tredwell, born in 1840, was the youngest child of Seabury and Eliza. Family lore has it that when she was a young woman, Gertrude had a suitor whose name was Luis Walton. We don’t know if Luis ever had the opportunity to enter the Tredwells’ formal Greek Revival parlor to meet Gertrude’s father, and perhaps ask for her hand in marriage; however, we can be fairly certain the young man had three strikes against him. First, Luis’ father was a physician, from England. Physicians, especially those trained in England, were held in much lower esteem than they are today. Moreover, Seabury, a believer in homeopathy (see my blog post of October 18, 2016), might well have cringed at the idea of an allopath like Luis’s father becoming a member of his family. Second, Luis and his family were Roman Catholic. The Tredwell family came from a long line of staunch Episcopalians, and anti-Catholic prejudice ran deep in antebellum New York.

Finally, his mother was Irish; well, the Tredwell servants were Irish! The Irish were on the lowest rung of the social ladder; the contempt towards members of this large immigrant group was strenuous and prevalent. Surely, Luis could not expect to meet Seabury’s high standards of eligibility for Gertrude’s hand in marriage. And so, after his brief appearance on the Tredwell stage, Luis Walton vanished forever. Or did he?

A Liverpool Lad

Luis Puertas Richard Walton was born in Liverpool, England on November 18, 1840. The England census record of 1841 indicates that at the time of Luis’s birth, the family had a boarder named Luis Puertas, who was listed as a “cigar dealer from foreign parts.” This must have been Luis Walton’s namesake!

Luis’s father, Henry Christmas Walton, was a licensed physician and apothecary. His mother, Elizabeth, was from Ireland. In 1849, Luis was baptized Roman Catholic at the Church of St. Peter in Liverpool.

A Neighborhood Boy

Life must have been difficult for the Walton family, for in 1844 Dr. Henry Walton declared bankruptcy in London. This may be what compelled him to immigrate to New York City in 1850 with his wife and four children, when Luis was 10 years old. The family’s first identified residence was on 590 Houston Street, on the corner of Mercer Street, a short walk from the Tredwell home on East Fourth Street. From there they moved to West 10th Street. By 1860, the family was comfortably ensconced in their own home on 37 West 16th Street, with five servants in their employ, indicating that the family’s financial situation must have vastly improved. We don’t know if Seabury was aware of their good fortune, but the young man’s religious and cultural disadvantages most likely prevailed in Seabury’s consideration of him as a potential son-in-law.

On to Medical School

We can only guess that Gertrude and Luis, living in such close proximity to one another, met somewhere in the neighborhood through mutual friends. We don’t know if they saw each other once Seabury expressed his disapproval. Luis may have been discouraged, but he clearly wanted to make something of his life. He pursued an education at Columbia College (then at Madison Avenue and 49th Street), earning his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1861, and three years later a Masters of Arts degree from the same institution. In 1870, after a two year course of study, he received his M.D. from the prestigious Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons (then located at 4th Avenue and 23rd Street). His father was one of his preceptors during his medical training.

.

A Successful Medical Career

Luis became a successful physician in New York City. After medical school, he resided and practiced for several years on West 17th Street; he then lived at various residences in the West 30s, until his final move to 73 West 50th Street, where he lived and maintained a lucrative general practice until his death. No doubt he followed his well-off private patients as they moved further uptown. He was a member of the Medical Society of the County of New York (1888-1903), as well as the New York Clinical Society.

Friendship with Edward Livingston Trudeau

In addition to his private practice, Luis served as an Attending Physician at both the Northern Dispensary (at Christopher Street and Waverly Place), and the Demilt Dispensary (at Second Avenue and East 23rd Street), charitable institutions that provided care to the poor and destitute of New York City. One of his colleagues at Demilt, who co-taught a class on diseases of the chest, was public health pioneer Edward Livingston Trudeau (1848-1915). Trudeau, himself a victim of tuberculosis, would in 1885 establish a famous sanatorium for victims of the disease in Saranac Lake in the Adirondack Mountains and, several years later, the first laboratory in the United States dedicated to the study of tuberculosis. In his autobiography, Trudeau makes frequent mention of Luis Walton, and credits his friend with drawing his attention to the work of the German physician Dr. Hermann Brehmer in establishing the practice of open-air treatment for tuberculosis. On a more personal level, Trudeau reveals Walton’s frequent calls and assistance during his bouts of illness:

“Dr. Walton was the greatest comfort at that time, and assured me he would look after my wife and ‘those dreadful little Trudeau brats,’ and he certainly kept his word. Walton all through the summer made regular pilgrimages to Little Neck [where Trudeau’s family stayed while he was recuperating in the Adirondacks], and reported to me of their welfare, while assuring me what a nuisance it was to have to look after another man’s family.”

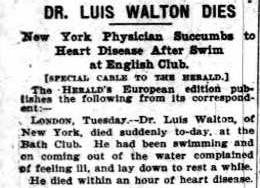

Oh, to Be in England

Luis clearly loved the country of his birth. An avid Anglophile, he was a member of the prestigious St. George’s Society of New York, a charitable organization that offered assistance to those born under the British flag. He also made frequent excursions to London, where he was a member of the elite Bath Club in Piccadilly. On September 8, 1903, after a swim at the Club, Luis died suddenly. He was 62 years old. His death was attributed to longstanding heart disease. He was buried at Kendal Green Cemetery in London. He left his estate to his surviving sister, Lucy Walton Mooney. The obituaries in professional journals that appeared at his death indicate that he was a highly esteemed physician, with a kindly manner and a deep compassion for his patients.

.

Lovers Apart?

We do not know the extent to which Gertrude and Luis maintained any relationship through the years. They must have corresponded with one another, for Gertrude referred to him in a letter to her nephew John T. Richards, dated November 18, 1924:

“You know Dr. Walton had “Angina Pectoris” but he lived for years with it – Strained himself climbing the Alps.”

Gertrude also kept in touch with at least one member of Luis’s family. The law firm hired by Gertrude and Julia to manage the estate of Sarah and Phebe Tredwell upon their deaths in 1906 and 1907 was Blandy, Mooney, and Shipman. The Mooney is Edmund Luis Mooney, a nephew of Luis Walton, who was with him in London at the time of his death. Coincidence? What do you think?

Assuming that Seabury’s disapproval of Luis is what precipitated the young man’s disappearance from Gertrude’s life, what kept the couple apart after Seabury’s death in 1865? Why did Gertrude never marry? Tradition has it that she vowed that if she couldn’t wed Luis, she would never marry. Perhaps her mother and older siblings were as much against the marriage as her father had been. Gertrude may have been reluctant to go against his wishes and the predominant Protestant culture of affluence and gentility in which she was raised. Or maybe the answer is simply that she never fell in love with any man after Luis. Whatever their reasons, there is one certainty: neither Gertrude, nor Luis, ever married.

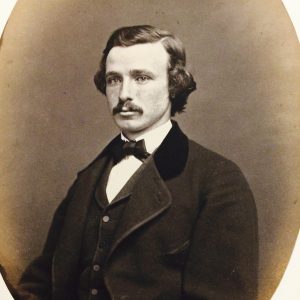

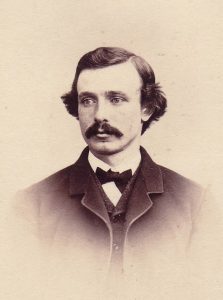

While researching Luis Walton, his 1861 graduate photograph was located in the Class Photograph Albums Collection at Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Museum staff recognized him from a previously unidentified photo in the collection (pictured above). We don’t know how the carte-de-visite of Luis came to be in the Tredwell home, but it remained there for the rest of Gertrude’s life. Valentine’s Day is the perfect occasion to celebrate the star-crossed love story of Gertrude and Luis!

Sources:

- ancestry.com England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975. Accessed 7/29/14.

- ancestry.com England Census, 1841. Accessed 7/31/14.

- ancestry.com New York, State Census, 1855. Accessed 7/29/14.

- ancestry.com United States Federal Census, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900. Accessed 7/31/14.

- ancestry.com U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989: 1902, 1903. Accessed 7/27/14.

- ancestry.com Directory of Deceased American Physicians, 1804-1929, JAMA Citation: 1903:41:736. Accessed 7/27/14.

- ancestry.com U.S. School Catalogues, 1765-1935: 1857-1861. Accessed 7/21/14.

- “Apothecaries Hall.” Lancet. Volume 1, p. 167. Accessed 7/21/14.

- “Bankrupts.” archive.thetablet.uk, pg. 8, 17 August, 1844. Accessed 7/21/14.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons. Catalogue of the Alumni, Officers, and Fellows 1807-1880, p. 122. Archives & Special Collections, A.C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons. Student Registers 1863-64 – 1878-79. Archives & Special Collections, A.C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons. Graduates of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Annual Catalog, 1870, p. 16. Archives & Special Collections, A.C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center.

- Columbia University. Class Photograph Albums Collection 1856-1902, UA#0131, Bib. ID 10278078, Box 79, 1861. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Butler Library, Columbia University.

- Medical Directory of the City of New York. New York: Medical Society of the City of New York, 1887-1900.

- Medical Register of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, 1872, p.158, 159.

- New England Journal of Medicine. Volume 149, September 17th, 1903, p. 332.

- newspaperarchive.com. London Standard, Friday, September 11th, 1903, p.7.

- newspaperarchive.com. London Monitor and New Era. Friday, September 18th, 1903, p. 11.

- Records of the Northern Dispensary, 1827-1955. Series 1, Box 3. New York University Archives, Bobst Library, New York University.

- St. George’s Society. A History of St. George’s Society of New York from 1770 to 1913. New York, [St. George’s Society], 1913.

- Trudeau, Edward Livingston. An Autobiography. New York: Doubleday, Doran, and Company, 1915.