“The Quality of Mercy:” Tredwell Philanthropy, Part 2

by Ann Haddad

The Tredwells’ Good Genes

Between 1821 and 1840, Seabury Tredwell’s wife, Eliza, gave birth to eight children. Considering the primitive medical care available in the antebellum period, and the resulting high rate of infant and childhood mortality, it is remarkable all of the Tredwell children lived to adulthood. Gratitude for their good fortune in light of the risks associated with childbirth may have been the impetus behind the Tredwells’ decision to support the New York Asylum for Lying-In Women (NYALIW).

Poor, Widowed, Abandoned Women

By the turn of the 19th century, many women found themselves struggling alone to support themselves and their children. Two major yellow fever epidemics, in 1795 and 1798, left many of them widowed. The influx of immigrants to New York City led to a population boom, but jobs were scarce for this group.

| . |

Husbands frequently needed to travel far from the city in search of employment. Some never returned. The incidence of alcoholism among the poor increased. As a result, many pregnant women lacked traditional family support, especially when assistance was needed as the time of their confinement approached.

It is ironic that, although America began to take on a sentimental attitude toward motherhood in the late 18th century, moralistic and religious convictions found many pregnant women, especially unwed ones, with no other recourse for medical care except the almshouse at Bellevue Hospital. “Respectable” women sought to avoid this institution, however, as it had a reputation for being a haven for prostitutes and other “degraded” women.

Wealthy Women to the Rescue

In the early 1820s, wealthy women began to focus their reform efforts on women’s causes, such as education and improved health care. In 1823, a group of benevolent women led by Mrs. Arthur Tappan, wife of the abolitionist Arthur Tappan, established the New York Asylum for Lying-In Women. Its aim was to provide temporary accommodations and skilled medical assistance to poor but “reputable” women during their confinement. “Reputable” in this case meant married; in fact, all applicants were screened by a committee, and were required to furnish a marriage certificate and character references to be considered for admission.

Once admitted, a woman was supplied with a bible and a list of rules, which stipulated that she could not leave the building, could not receive visitors, and could not remain longer than four weeks after delivery. Alcohol was forbidden; that which was used for medicinal purposes was kept in a locked cabinet. Emphasis was placed on order, morals, and obedience. To emphasize their noble mission, the board of the NYALIW included the following passage from William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice in their first Annual Report:

“The quality of mercy is not strain’d.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from Heaven

Upon the place beneath: It is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.”

By Women, for Women

Although it employed a resident male physician, the NYALIW was unique in that it was managed and run by women: it had an all-female board, and barred male medical students from entering the institution. Births were attended by either a midwife or the matron. Postpartum care and vaccination of all newborns against smallpox were provided before discharge.

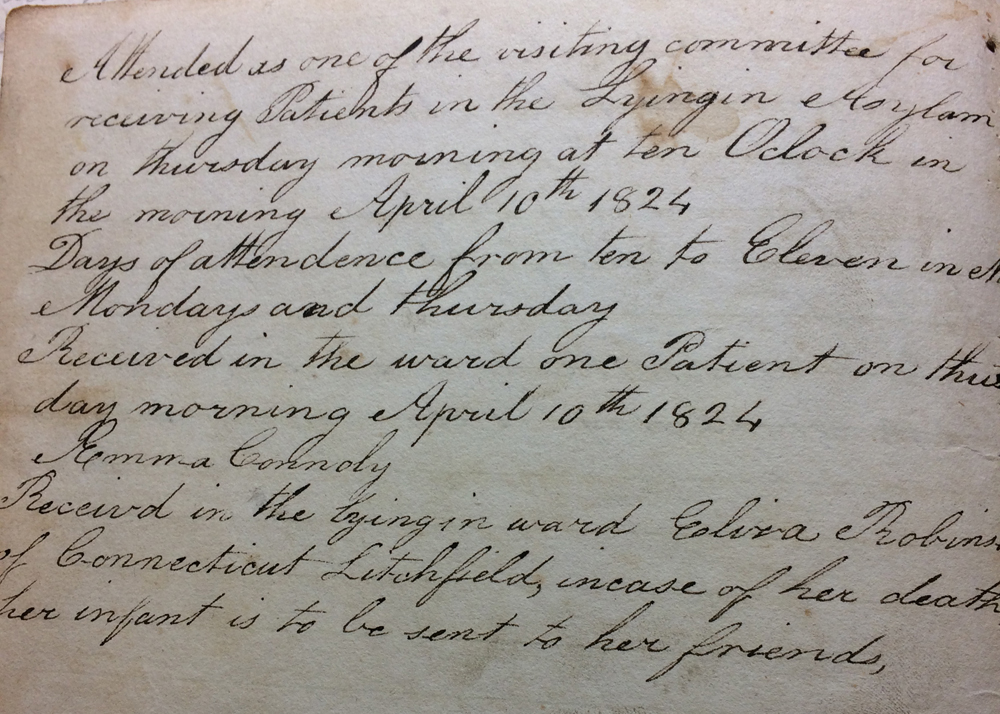

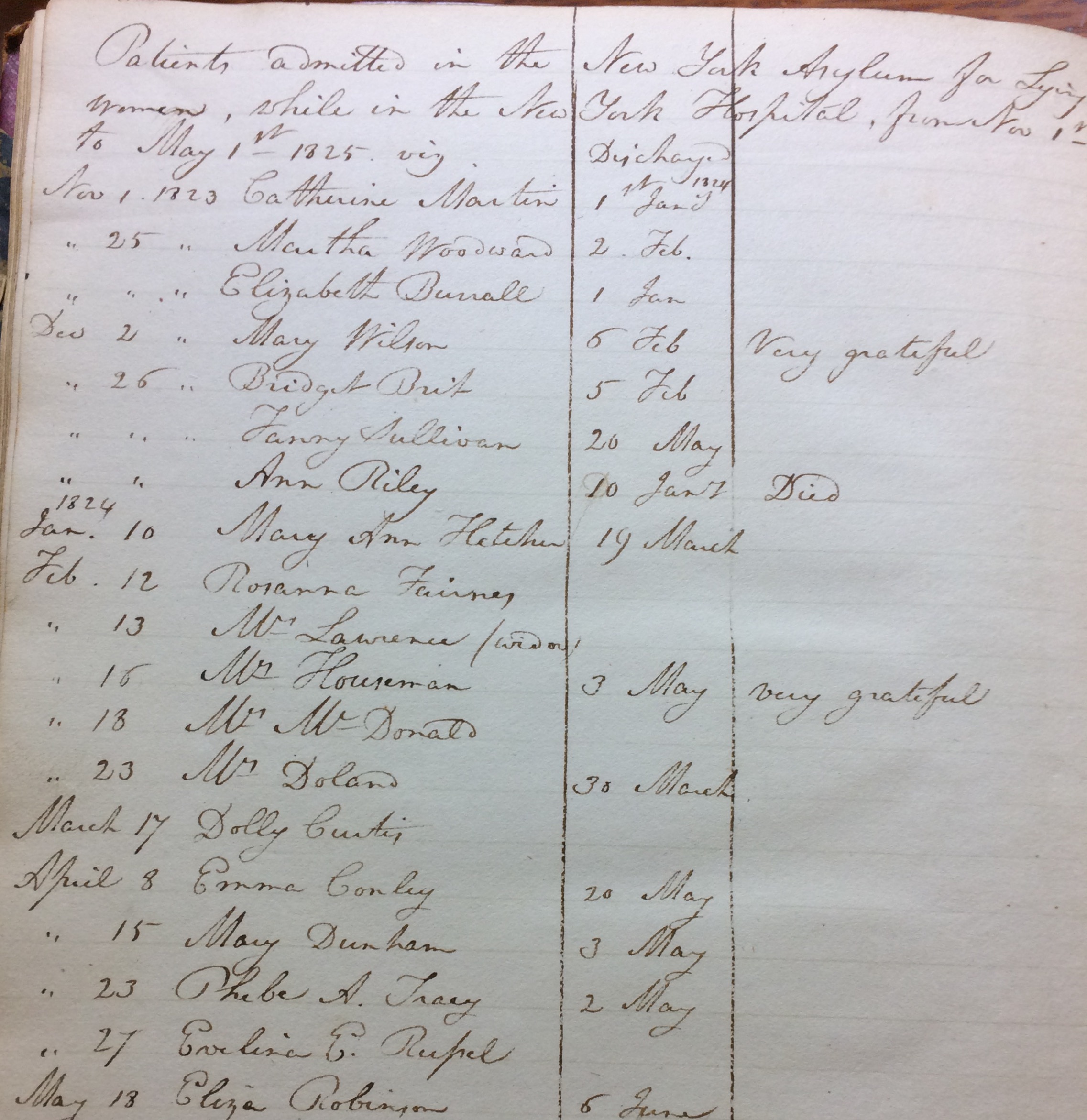

The charity’s first home was the Square Ward of New York Hospital, then located on Broadway between Anthony Street (now Duane Street) and Catherine Street (now Worth Street), which opened for admissions on November 1, 1823. The first patient was Catherine Martin, the wife of a weaver, John G. Martin, who had left his wife three months previous to look for work. Mrs. Martin was admitted on the 21st of November, and gave birth to a healthy child. She was discharged on January 1, 1824.

The Tredwells Support NYALIW

Within a few years the NYALIW outgrew its ward at New York Hospital, and sought donations for the purchase of larger quarters. In 1825, Seabury Tredwell was among the first group of donors, giving $24; the amount collected enabled the charity to move to larger facilities on Greene Street. In 1830, the charity had garnered sufficient funds to relocate to a three story building on 83 Marion Street (now Lafayette Street), where it remained until its move in 1885 to 139 Second Avenue, between 8th and 9th Streets, in the heart of the 14th Ward.

In 1832, Seabury once again donated to the NYALIW. His $25 subscription made him an “Honorable Member for Life,” along with other prominent citizens such as Joseph Brewster, Philip Hone, Duncan Phyfe, and Benjamin and George W. Strong. No doubt the Tredwells felt strongly about this cause, because from 1828 to 1861 Eliza Tredwell, an Annual Subscriber, donated $3-$5/year.

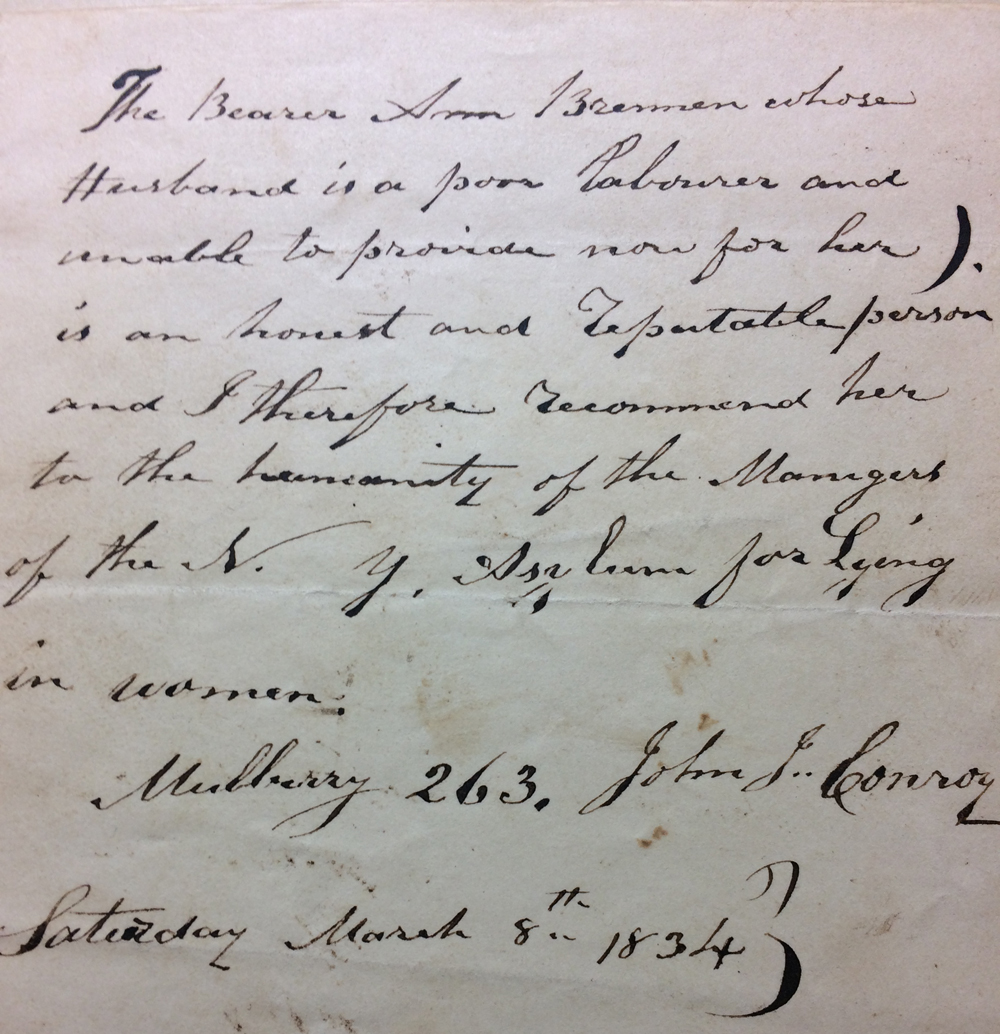

As a Subscriber, Seabury was permitted to recommend two women per year to the institution. One supporter who wrote a letter of recommendation for a woman in need was John J. Connor, who wrote the following:

“The bearer Ann Brennen whose husband is a poor laborer and unable to provide now for her is an honest and reputable person and I therefore recommend her to the humanity of the Managers of the N.Y. Asylum for Lying in women.

Mulberry 263. John J. Connor

Saturday March 8th 1834″

.

Heartbreaking Stories

One story in the NYALIW’s minutes, which is typical of the circumstances that befell many poor women, is that of Mrs. Anne Croaker, who applied for admission on September 13, 1828. Her husband, who had worked as a locksmith for seven years for a Mr. Pye, had recently died. His death was hastened by a dose of arsenic, which was sold in error by the druggist. Mrs. Croaker, left completely destitute, lived with her five young children in a room on Canal Street, which had been loaned by a friend. The Admissions Committee visited Mr. Pye, who vouched for Mrs. Croaker’s character; he stated that she was forced to “sell her most valuable things to procure comforts for him [Mr. Croaker] during his illness.” Mr. Pye generously offered to provide for the children during their mother’s confinement.

Women seeking relief came from Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and outlying parts of New York State. Mrs. Collin Reed, a wealthy New Yorker who served on the Admissions Committee for NYALIW in 1824 and 1825, noted the following in her ledger book:

“Received in the lying-in Ward Eliza Robinson of Connecticut, Litchfield. In case of her death, her infant is to be sent to her friend. [Eliza is] clean and tidy, but very destitute. She supports herself by taking work from the slop shops. Received on the 18th of May, left June 6th.”

In 1831, due to the insufficient numbers of married women who were seeking assistance at the doors of NYALIW, the institution broadened its admission requirements to include unmarried women. It also began making home visits to extend its outreach. For several years previous, however, some committee members had begun to overlook the questionable tales of woe and the dubious marriage certificates furnished by some applicants; thus a number of unmarried women were permitted to enter.

NYALIW’s Employment Agency

| . |

Upon their discharge, the administration sought to place unmarried women as wet nurses in respectable families for one-year periods. After careful screening at the time of admission, observation throughout their confinement, and physical examination by a physician at the time of delivery, the charity was able to offer a guarantee of the health and character of the wet nurses hired by prospective upper class families. In 1828, NYALIW proudly announced that “Of fifty who have been discharged from the house…23 have obtained places as wet nurses in respectable families.” No mention was made of the fact, however, that these women most likely would have had to find a wet nurse for their own infants.

At its 48th annual meeting, held on April 19, 1871, NYALIW reported that since opening its doors, it had gratuitously assisted 16,329 women. It noted that in 1870, 86 patients had been treated at the Asylum, and 188 more at their homes.

In 1894, NYASIW changed its name to the Old Marion Street Maternity Hospital; in 1899, it merged with the New York Infant Asylum. The charity ultimately became the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center.

A Christmas Recipe from 1825

Like many 19th century women, Mrs. Reed, NYALIW’s Admission Committee Member, used her manuscript ledger as a recipe book as well as a diary and account book. Here is her recipe for a festive “Rich Plum Cake”:

Of flour, butter and sugar 3 pounds each, 2 doz eggs, 4 lb and a half of currents 6 lb of raisins, mace, cinnamon, nutmeg each ounce 1/4 oz of cloves, 2 tablespoon full of ginger 2 gills of wine, 1/2 pound of citron.

Wishing you a joyous holiday season! Merry Christmas!

Sources:

- “Anniversary of the New-York Asylum for Lying-In Women.” New York Times. April 20th, 1871, p. 2. timesmachine.nytimes.com. Accessed 12/6/16.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Golden, Janet. A Social History of Wet Nursing in America: From Breast to Bottle. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Managers of the New York Asylum for Lying-In Women. Annual Reports, 1824-1855. www.archive.org Accessed 11/15/16.

- Minutes, 1823 Nov. 1-1831 Feb. 28. New York Asylum for Lying In Women. BV 89584. New York Historical Society Manuscript Collection.

- New York Asylum for Lying-In Women Materials. Delaplaine Family Papers. 89638. Box 4, Folder 9. New York Historical Society Manuscript Collection.

- Quiroga, Virginia A. Metaxas. Poor Mothers and Babies: A Social History of Childbirth and Child Care in Nineteenth Century New York City. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1989.

- Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice, Act IV, Scene 1.

The Doctor in the House is a Homeopath!

by Ann Haddad

A Discovery in the Archives

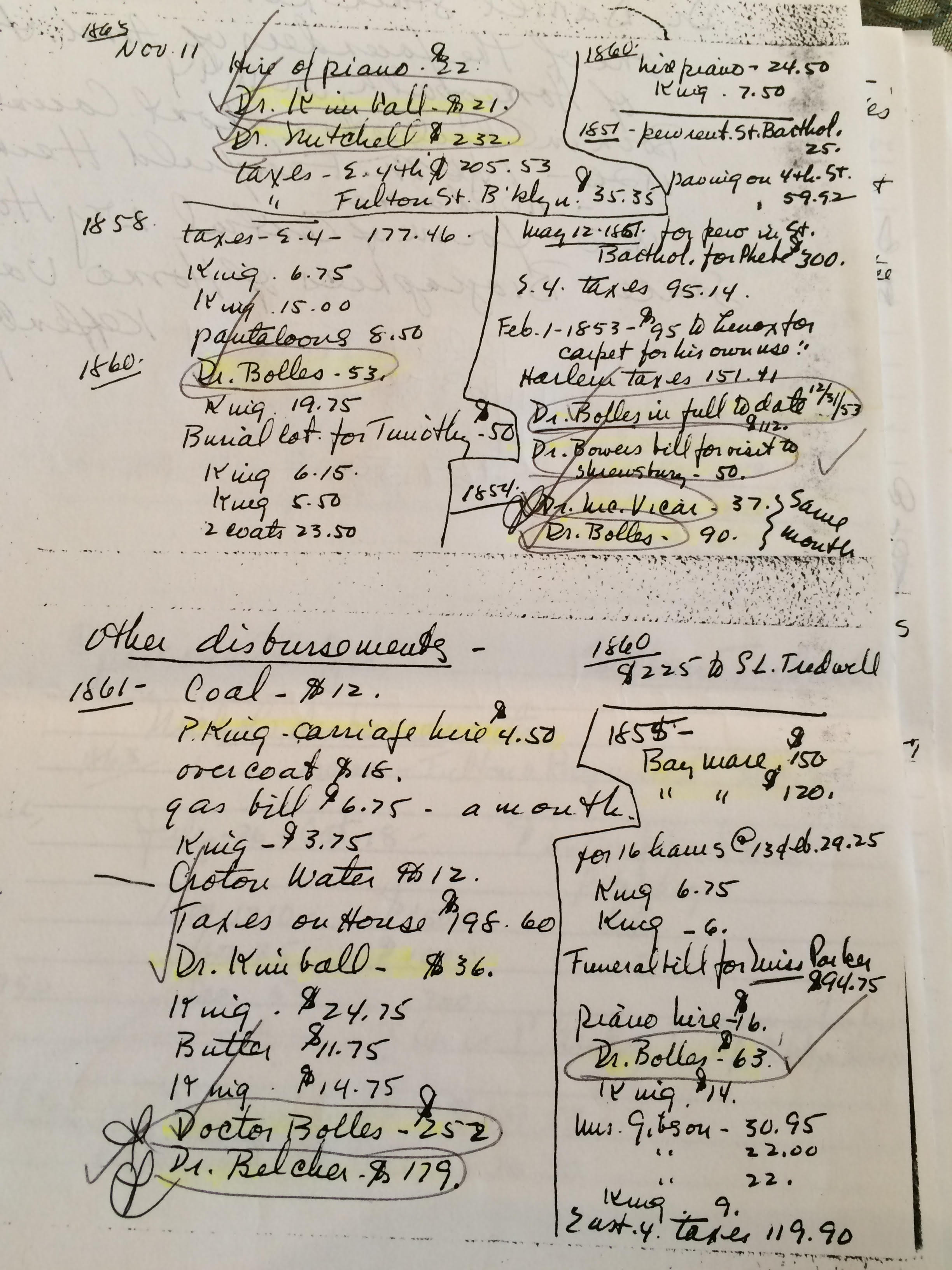

Among the papers in the Tredwell family archives are notes, copied by a staff member from Seabury Tredwell’s personal ledger, that date from 1851 until his death in 1865. (Unfortunately, the ledger is missing.) Judging by his detailed entries of monthly debits and credits, Seabury kept a tight hold on his family’s purse strings. He carefully included expenses both large and small, such as his pew rental at St. Bartholemew’s Church in 1851 ($300), frequent carriage rentals ($8 average), and 16 hams ($29.25).

The most exciting information gleaned from Seabury’s ledger book, however, relates to payments to various physicians for 18 house calls made during those 14 years. Based on standard medical practice of the time, that would have meant a lot of purging and bloodletting. But most likely, not a drop of blood was shed in the Tredwell household in the name of therapy; for in researching the medical practices of the six doctors who ministered to the Tredwell family, it was discovered that, far from being mainstream practitioners, they were all non-traditional homeopaths.

The Typical Treatment: Arsenic and Leeches

Prior to the development and gradual acceptance of germ theory in the mid-to-late 19th century, summoning one’s physician to treat an illness was risky at best. Orthodox medical practice offered little in the way of treatments, and the choices were harsh, potentially toxic and painful, and largely futile. Mercury, arsenic, and lead were used to elicit violent purging and vomiting; bloodletting and use of leeches caused severe anemia, which only worsened the patient’s condition. As a result, laymen developed a severe distrust of physicians, and expressed their doubts and criticisms publicly.

The Emergence of Homeopathy

| . |

As “regular” physicians (or allopaths) struggled to identify more evidence-based treatment modalities, homeopathy emerged as a sophisticated and gentler alternative to the barbaric practices of regular medicine. The origin of homeopathy dates to the work of the German physician Samuel Hahnemann (1755-1843). It was introduced in the United States by Hans Burch Gram (1786-1840), who began practicing medicine in New York City in 1825. Treatment was based on the “Laws of Infinitesimal Dose” and the “Law of Similars,” in which minute and extremely diluted doses of medicines were administered to produce symptoms similar to those of the disease being treated, thereby allowing the body to naturally heal. This was perceived as a gentler, more holistic approach to treating disease.

The recovery rates of patients treated with homeopathy were higher than those treated by orthodox medicine, simply because the new remedies did little or nothing to harm the patients. The apparent success of this new approach, especially during the cholera epidemic of 1832, led many regular physicians to seriously consider “converting” to more homeopathic remedies. Many of these were physicians who had trained at highly regarded allopathic medical schools.

.

The Practice Grows

In 1834-1835, both the New York Homoeopathic Society and The American Journal of Homoeopathia were established. By 1844, the number of practicing homeopaths in the United States had grown to such an extent that the American Institute of Homeopathy was formed. In 1860, the Homoeopathic Medical College of New York was opened and by 1900, the city had more than 100 homeopathic hospitals, clinics, and dispensaries, including one on Bond Street, two blocks away from the Tredwells’ home.

If Mark Twain Believes in It …

Many highly respected public figures of the day espoused the benefits of homeopathy, thereby contributing to its increasing popularity. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Cullen Bryant, Daniel Webster, and Henry James were advocates of its methods. Homeopathy was also very popular among women, including authors Harriet Beecher Stowe and Louisa May Alcott, and members of the clergy. Mark Twain, another believer, said in 1890 that homeopathy:

“…Forced the old school doctor to stir around and learn something of a rational nature about his business, … And you may honestly feel grateful that homeopathy survived the attempts of the allopaths to destroy it.”

The number of homeopaths in New York City grew from 93 in 1857 to 322 in 1904, which was over 15 percent of all practicing physicians.

Traditional Medicine vs. “Quackery”

The reaction by the majority of mainstream physicians and pharmacists to the new practice of homeopathy was fierce and prolonged. Labeled as “quacks” and “irregulars,” homeopaths were perceived as a threat to the medical establishment, for financial as well as theoretical reasons. The traditional physicians were losing patients, and the apothecaries lost business, because homeopaths typically prescribed one medication at a time, and in minute doses. In 1847, the established members of the New York medical community united against the practice of homeopathy and formed the New York Academy of Medicine, and on February 3rd of that year, the first President of the Academy, Dr. John Stearns, had this to say about homeopathy in his inaugural address:

“No man in the full exercise of his reason can believe in the truth of this strange doctrine; and if he attempts to practice upon the principles which that doctrine inculcates, he must possess a depraved moral faculty.”

That same year, the American Medical Association was founded, largely to impose severe restrictions on all forms of alternative medicine. The battle of the allopaths and the homeopaths was fought in the newspapers. The following anonymous poem, which appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in November 1849, lambasts the heavily diluted therapies prescribed by homeopaths:

“Take a little rum,

The less you take the better,

Mix it with the lakes

Of Wenner and of Wetter.

Dip a spoonful out–

Mind you don’t get groggy–

Pour it in the lake

Winnippisseogee.

Stir the mixture well,

Lest it prove inferior;

Then, put a half a drop

Into Lake Superior.

Every other day

Take a drop of water;

You’ll be better soon,

Or at least you ought to.”

Seabury Tredwell Meets Homeopathy

We do not know why or when Seabury Tredwell began to turn to homeopaths for his family’s medical care. There were at least four physicians in his immediate and extended family; although the nature of their practices is unknown, they were most likely allopaths. Seabury may have been influenced by colleagues in the mercantile world, two of whom, Robert B. Folger and Ferdinand Little Wilsey, studied homeopathy and established medical practices after being successfully treated by Dr. Gram in 1826.

| . |

Who Were These Guys?

Whatever his motivation, records indicate that between 1853 and 1865, Seabury relied exclusively on homeopathic physicians. Dr. Richard M. Bolles (1797-1865), made the most frequent house calls to the Tredwell family between 1853 and 1861. He adopted the tenets of homeopathy in 1840, and his practice diminished as a consequence. Bolles remained an advocate of this alternative treatment, and served as president of the Hahnemann Academy of Medicine. He also worked in several of the homeopathic dispensaries in the city. His Poetic Descriptions of the Chest-Pains and their Appropriate Remedies was famous among homeopaths. Dr. Bolles’ bills to the Tredwell family over eight years totaled $693. He died in August 1865, five months after the death of his patient, Seabury Tredwell.

Dr. Benjamin F. Bowers (1796-1875), who was considered very influential on the growth of homeopathy in New York, made one visit in 1853 to the Tredwells’ farm in Rumson, New Jersey. Dr. Bowers was expelled from his position at the New York Dispensary in 1839 for providing non-traditional medical care. He later served as president of the Homeopathic Medical Society of New-York, and was involved with the Protestant Half-Orphan Asylum (as was his colleague Dr. Bolles, who served as Medical Supervisor), a charitable institution that:

“… has been exclusively under homeopathic treatment for the past 24 years with the most gratifying results, having had an average mortality as compared with all the other asylums in the city, of only one to three.”

Dr. George Belcher (1818-1890), who ministered to Seabury Tredwell during his final illness in March 1865 (Dr. Bolles having retired some years prior), had one of the largest medical practices in New York City. An 1839 graduate of Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, he “converted” to homeopathy in 1844. He signed Seabury Tredwell’s death certificate, listing Bright’s Disease (now nephritis, or kidney disease), as the cause of death. On December 31, 1865, he submitted his bill for $70 for his final visit to the Tredwell home on East 4th Street.

Following in Father’s Footsteps

After his death in 1865, at least one of Seabury’s children continued to turn to homeopaths for medical treatment. Elizabeth Tredwell Nichols (1821-1880), Seabury’s oldest child, was a patient of Dr. John Samuel Bassett (1830-1912), a Harvard-trained physician with a practice on West 31st Street, near the Nichols’ residence on Fifth Avenue and 34th Street. Dr. Bassett was a highly regarded physician to many of New York City’s most distinguished families, including the Astors, Chandlers, and Rhinelanders. A respected member of the American Institute of Homeopathy, Dr. Bassett was frequently consulted by other physicians because of his skills as a diagnostician. In 1880, he attended Elizabeth in her final struggle with chronic bronchitis. Elizabeth was 59 years old at the time of her death.

Demise, Then Resurgence

After the turn of the century, the popularity of homeopathy gradually declined as a result of the increasingly scientific approach and rational treatments of regular medicine. By 1923, only two homeopathic colleges remained in the United States, and by 1950 they too had closed.

Within the past 40 years, homeopathic medicine has re-emerged onto the medical scene. It is not unusual for mainstream physicians who focus on a holistic approach to patient care to incorporate homeopathy in their practices, and homeopathic remedies are sold in pharmacies alongside traditional medicine. The Tredwells, no doubt, would feel perfectly at home.

Sources:

- Bowers, Benjamin F. “Opposition to Homeopathy in New York,” in The North American Journal of Homeopathy. Vol. 15, May, 1867, p 580-604. http://books.google.com. Accessed 9/26/16.

- Bradford, Thomas Lindsley. Biographies of Homeopathic Physicians, Vols. 3, 4, 19, 21, 22: Beach-Bixby. Philadelphia, 1916. www.archives.com. Accessed 9/22/16.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Friday, November 9, 1849. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/30/16.

- Duffy, John. History of Public Health in New York City, 1625-1866, Volume 1. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1968. p. 464-471.

- “Homeopathic Directory.” New England Medical Gazette. April, 1871, p. 190-191. www.archive.org. Accessed 9/8/16.

- King, William Harvey, Ed. History of Homeopathy and Its Institutions in America. New York: Lewis Publishing Co., 1905. www.archive.org Accessed 9/28/16.

- Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic, 1982.

Ullman, Dana. A Condensed History of Homeopathy. www.homeopathic.com. Accessed 2/28/16.

![Henry Monnier. “Allopath and Homeopath argue over method of treatment. [183-]”. (National Library of Medicine.)](https://merchantshouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/allopath-argue.jpg)