“A Scene of Radiant Joy:” The Wedding of Elizabeth Tredwell & Effingham Nichols

by Ann Haddad

This is the fourth and final of a series of blog posts on mid-19th century courtship and wedding customs. Click for Part One, on 19th century courtship; Part Two, on marriage proposals and engagements; and Part Three, on wedding preparations.

A “Royal” Wedding in Old New York City

The recent marriage of Prince Harry, the younger grandson of Queen Elizabeth, and Meghan Markle, an American actress, caused a stir both in England and in America. Even those who scoff at the notion of monarchy may have been entranced by the pomp and spectacle surrounding the “Royal Wedding,” finding it to be both thrilling and heartwarming.

In 19th century New York City, there was a flourishing royalty of a sort, led by the “merchant princes,” whose success in business and resulting wealth endowed them with economic and social power. Seabury Tredwell was one such wealthy merchant, and the marriage of his eldest daughter, Elizabeth, to Effingham Nichols, on April 9, 1845, could also be considered a ‘“royal” event, for it united two established families who occupied prominent positions among the aristocratic elite of New York society.

Why April?

Why did Elizabeth choose an April wedding, and on a Wednesday? Spring was always a popular time for nuptials; perhaps Effingham’s work as an attorney eased up a bit in April. Or perhaps Elizabeth was familiar with the old adage:

“Marry in April when you can,

Joy for Maiden and for Man.”

Tuesdays, Wednesdays or Thursdays were usually chosen for a wedding, likely because the clergyman was frequently occupied with his regular pastoral duties on the weekend.

Church or Parlor?

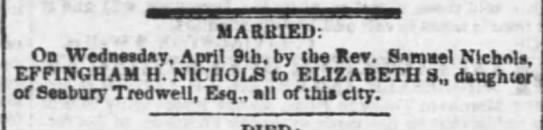

In 1845, American wedding practices were on the cusp of great change. Weddings were evolving from simple, intimate family affairs to elaborate public events, rich in tradition and ritual. We have no surviving records that describe the Tredwell and Nichols union. The only certainty is the date of their wedding and the officiant, the Reverend Samuel Nichols, father of the groom. (Coincidentally, the Reverend James Milnor, who officiated at Seabury and Eliza’s wedding on June 13, 1820, at St. George’s Chapel, died on April 8, 1845, the day before Elizabeth’s wedding.)

Elizabeth and Effingham’s marriage announcement, published on Friday, April 11, in the New York Evening Post, did not mention a church wedding, so chances are that the couple were wed in the elaborate Greek Revival double parlor of the Tredwell home on Fourth Street.

.

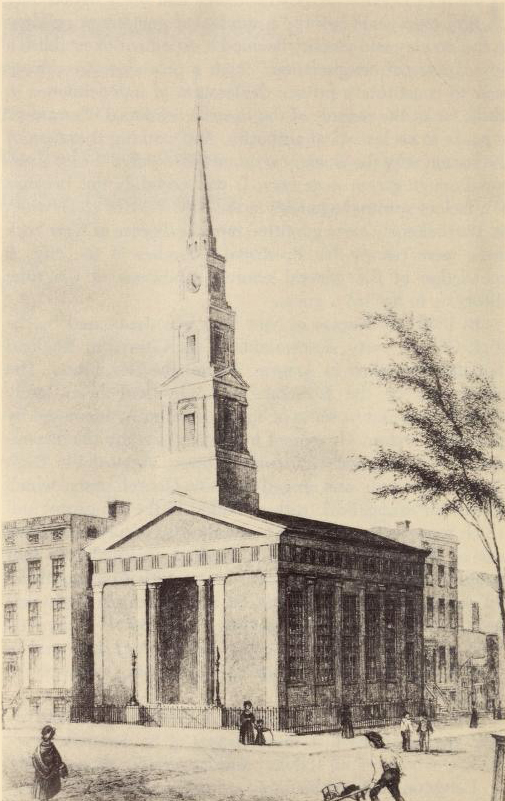

.

If the couple had been married in church, it most likely took place at St. Bartholomew’s, then located at Great Jones Street and Lafayette Place, one block away from the Tredwells’ home. In the mid-19th century, there was a growing trend away from small weddings held in the bride’s family parlor, in favor of a church wedding. A church’s large public space accommodated more guests. If Elizabeth and Effingham had been married at St. Bartholomew’s instead of at home, the Tredwells might have chosen a church setting for this reason; or because of the close ties both families had with St. Bartholomew’s. Effingham Howard Warner, the groom’s uncle and namesake, was one of its founders, and the Tredwells had worshiped there since its consecration in October 1836, one year after their move to the elite Bond Street neighborhood.

Your Hosts: Mr. and Mrs. Tredwell

Whatever location was chosen for the wedding ceremony, there was never any choice as to the venue for the reception: custom dictated that it be hosted and paid for by the bride and her parents at their home. As Elizabeth was the first of their children to marry, Seabury and Eliza likely seized the opportunity to display their wealth, refinement, and sophistication, both for their children’s benefit (five unmarried daughters were still at home), and to impress their guests.

Set and Lighting Design for the Performance

In preparation for Elizabeth’s marriage, the entire Tredwell house must have been turned upside down, for although the grand double parlor was the main stage for the action, the entire house required cleaning from top to bottom; everyone, especially the Tredwells’ four servants, was engaged in this task. New furnishings may have been purchased; and, to show the home to its best advantage, additional lighting may have been rented for the occasion. The house was elaborately decorated with an abundance of white flowers that covered nearly every surface, possibly ordered from Dunlap & Carman, located at 635 Broadway, near Bleecker Street. Musical entertainment, ranging from a soloist at the pianoforte to a quartet, may have been arranged; and dancing was common at evening wedding receptions.

In a diary entry from Wednesday, February 19, 1845, Mrs. Abiel Abbot Low described the process of readying a house for a wedding reception:

“Mr. Nevers made preparations for lighting the house. This afternoon he is having a chandelier with four burners in each parlor, four solar lamps at the folding doors, and two candelabras for five candles each, on either side of the mirrors. Abbot bought a handsome brussels carpet for the tearoom, and a handsome sideboard, as a pleasant surprise for me. Borrowed a few pieces from our friends, including a full length mirror for the ladies’ dressing room.”

Mary Harris Lester summed up the whirlwind of activity surrounding the house preparations when she hurriedly wrote in her diary on Monday, December 15, 1847, just several days before her wedding:

“Mother went with me today to order things for next Monday evening, have a great deal to attend to at present.”

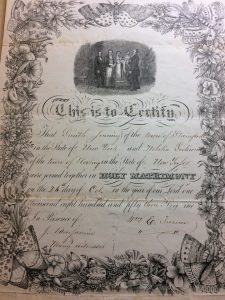

License Not Required

In 1845, the only available record that provided proof of marriage was the bridal certificate, issued by the church where the wedding was held, or, in the case of home weddings, obtained by the clergyman from his own parish church. Prior to 1847, no marriages were recorded by any cities or towns in New York State. Wedding announcements were traditionally published in local newspapers within several days of the event.

Dressing the Bride

The Art of Good Behavior (1845) states unequivocally that “it is the duty of the bridesmaids to assist in dressing the bride.” On Elizabeth’s wedding day, she was almost certainly assisted by her sisters Mary (then age 20) and Phebe (age 16). They most likely dressed in one of the bedrooms on the third floor. After dressing themselves in their own simple white dresses, the sisters helped Elizabeth into her wedding dress; tied up her silk or satin slippers; affixed her lace or net veil with a wreath of orange blossoms, as was the fashion (being careful not to disturb Elizabeth’s hair, which had been dressed at home by a hairdresser); put on her gloves; and, when all else was in readiness, hand her a white leather prayer book or embroidered handkerchief to carry.

Toasting the Groom

The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852) states the essential requirements of the groomsmen: “Young and unmarried they must be, handsome they should be, good humored they cannot fail to be, and well dressed they ought to be.”

It was customary for the groom, after dressing at home, to meet his groomsmen at the home of his future wife. Upon arriving at another third floor bedroom in the Tredwell house, Effingham may have found his friends gathered around a punch bowl, ready to toast him with a tumbler or two, and to make sure that he, too, enjoyed a nip of “liquid courage.”

The chief groomsman also needed to be certain that the wedding ring, wrapped in silver paper, was securely placed into the groom’s waistcoat prior to the ceremony. Among his other duties was to greet the clergyman upon his arrival and introduce him to the family and friends who gathered in the parlor to witness the ceremony. It is at this time that he obtained the certificate of marriage from the clergyman, to present to the groom after the reception.

Here Come the Bride and Groom!

Once a servant announced to the gentlemen that the ladies were ready, the men joined their partners in the hallway, and, arm in arm, with the bridal pair bringing up the rear, descended the staircase to the parlors on the first floor, where the invited guests were waiting. Even if Elizabeth had been married in church, her father, Seabury, most likely did not escort her; contemporary diaries of this period indicate that the bride and groom simply took their place before the altar. It wasn’t until the mid-late 19th century and the prevalence of church weddings that the ritual of the father “giving away his daughter” became commonplace.

Upon entering the front parlor, the bridal party positioned themselves in a semicircle facing the guests, who were either seated or standing, depending on the number attending. The bride stood to the right of the groom, and was flanked on her right by her bridesmaids; the groomsmen stood to the left of the groom. The clergyman then proceeded with the ceremony, taken from The Book of Common Prayer; vows were exchanged; then the groom removed from his waistcoat pocket the plain gold wedding ring (perhaps engraved with their initials and the wedding date) and placed it on the fourth finger of the bride’s left hand.

Mrs. Nichols

Once the nuptials were completed and Effingham kissed his bride, the clergyman addressed Elizabeth for the first time by her newly acquired name, “Mrs. Nichols.” The newlyweds were congratulated first by Seabury and Eliza, then Effingham’s parents, followed by family and friends, who were escorted to the couple by the chief groomsman.

After all the congratulations had been offered, the bridal party was free to mingle with the guests.

At some point after the ceremony, it was the responsibility of the chief groomsman to quietly thank and compensate the clergyman for his services. The sum was determined by the financial ability and generosity of the groom.

Henry Patterson wrote in his diary of his wedding, which took place on Thursday, July 18, 1844:

“Thursday [the wedding day] I spent at my usual business until four o’clock, [note that he worked as usual on his wedding day!] then went home and dressed. ….went to Mrs. Wright’s at 7 o’clock. From then until a quarter after eight the company was assembling and preparations going forward then all being ready, Ophelia acting as bridesmaid and Turner as groomsman, we walked into the room, and were immediately married by Mr. Hatfield. The ceremony was short, but impressive, and suited us both. After receiving the congratulations of our friends who were present, the evening was passed with conversation, a little music, and by eleven o’clock all had dispersed.”

And on December 27, 1855, Edward Tailer wrote sweetly in his diary of his wedding to Agnes Suffern, and of the moment when he first heard his wife addressed by her married name:

“The Dr. read the service in an impressive manner and occasionally a tear could be seen trickling down the face of those who loved us both, and who had our interests at heart, but a few moments sufficed to proclaim us to be man and wife, and it was not until I heard our mutual friends calling Agnes “Mrs. Tailer,” that I could realize that any change had taken place or that new responsibilities have been assumed by me. It was a pleasant affair, and all appeared to enjoy themselves, about 110 persons being present. Numerous were the congratulations of our friends and if all the kind wishes which were expressed within my hearing could only be realized, I shall be a very happy man.”

Eat, Drink, and Faint!

Guests to a home wedding were usually invited for 8 p.m. Other than the requirement that the wedding reception be held at the bride’s parent’s home, there were no hard and fast rules about the number of guests, the type of reception, or the entertainment. Upon arriving at the Tredwell home, guests proceeded directly up to the second floor, where Seabury and Eliza’s bedroom had been turned into “dressing rooms,” for guests to fix their hair, adjust their gowns, or polish their boots, assisted by one or two servants. They then went down to the front parlor, where Mr. and Mrs. Tredwell greeted them as for any sociable.

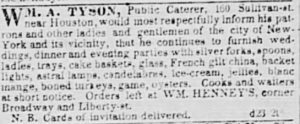

Depending on the size of the guest list, Mrs. Tredwell may have elected to have the wedding buffet feast catered, perhaps by William A. Tyson (see advertisement of December 24, 1846), who, in addition to preparing the food, provided equipment, servers and cooks to assist with the reception. The lavish “wedding supper,” which was typically served at 11 p.m., consisted of oysters, cold meats, fish, fruits, and various confections. Beverages included lemonade, punch, wine, and champagne. The table was usually set up in the rear parlor and the overflow of the many guests spilled into the halls and tea room. Imagine the scene of the Tredwell front hall, tearoom, and both parlors crowded with guests trying to reach the supper table!

Mrs. Abiel Abbot Low wrote in her diary Sunday, February 2, 1845, of one parlor wedding she attended:

“I should judge there were more than three hundred present during the evening. I never was at so crowded company before. There was a band of music and some dancing during the evening. Supper was announced at 11 o’clock and a most bountiful and elegant repast it was, but such crowding in a supper room I never witnessed before. The drawing room was so warm at one time, and the air so perfumed with the profusion of flowers that several of the ladies fainted. We returned home between 12 and 1 o’clock.”

John Hadden, a young man who lived at 20 Lafayette Place, right around the corner from the Tredwells, could have been describing the Tredwell home when he wrote of a lively and somewhat chaotic wedding reception he attended on Tuesday, January 17, 1843:

“It was a very pleasant party. The whole house was open. The two drawing rooms for dancing, and on the back stoop which was enclosed a small room [like the Tredwell tea room] with a little refreshment, punch and lemonade with cake, the piazza having a couch where the bride sat and received the company. The second story back room for the ladies, the front room for the gents. As usual at most crowded parties the company went to the supper room about 3/4 of an hour before things were ready and we had to stand until everything was in order. Before this was accomplished Mr. Wright took up a bottle of champagne from the table and was about to open it, one of the waiters told him the table was not ready yet, but he took it out of the supper room with him and opened it somewhere else.”

For those of lesser financial means, a simple menu of wedding cake, wine, and lemonade was customary. Usually within two hours after the reception commenced, the bride quietly left the festivities and, escorted by her attendants, retired to her bedroom. There they helped her undress and perform her “night toilette.” According to The Art of Good Behavior (1845): “The groom retires without ceremony or notice.” According to contemporary diaries, guests typically lingered until anywhere between 11 p.m. and 2 a.m.

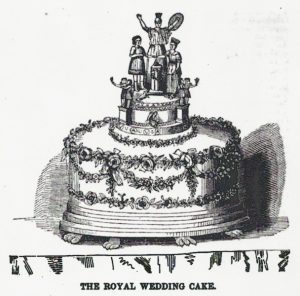

Let Them Eat Cake

Until the mid-1850s, when tiered cakes became popular, the bridal cake was usually of a single layer, and typically consisted of a rich, dark fruitcake covered in almond paste and a hard, white sugar icing. It was either baked at home or, as was probably the case with Elizabeth’s cake, ordered from one of the many confectioners in the city that prepared fancy desserts, such as James Tompson’s Premium Bakery, located at 40 Lispenard Street.

The cake, usually decorated simply with fresh flowers, was placed on a rectangular table covered with a white cloth. When the cake was ready to be cut, Elizabeth and Effingham sat in front of it, surrounded by their bridesmaids and groomsmen, who stood at either side, while their parents took their places at either end. The rector stood opposite the bride and groom. Champagne was usually served, then the chief groomsman offered a toast to the newly married couple, and to the health of the parents of the bride. The bride then cut the cake (sometimes with a special saw, as the cake was typically too thick and hard to cut with a regular knife!), which her bridesmaids, assisted by the servants, distributed to the guests.

Wedding Favors for Dreaming

It was customary for the bride and groom to give away tiny boxes of wedding cake to guests. These slices were cut from a second cake baked specifically for this purpose before the wedding. Many stationers, such as Stouts, located at the corner of Broadway and Maiden Lane, advertised special cake boxes, as in this ad from December 21, 1848: “elegant boxes for cake at $8 per hundred.” Mary Harris Lester wrote on the eve of her wedding on December 18, 1847, “… house all in order quite busy all evening in tying up boxes of cake.”

The evening before the wedding, the bridesmaids helped the future bride to ready the cake boxes, which were distributed to the guests upon their departure from the reception.

It was important for newlyweds to let their friends and acquaintances know when they would commence receiving well-wishers at their home upon returning from their bridal tour. A new “at home” card was made expressly for this purpose; it was attached to the wedding cake boxes as a convenience for the guests. Stout’s wedding cards were advertised as “elegantly engraved and printed…”

Etiquette and fashion experts stressed that a woman may not distribute a card bearing her married name until after she utters her marital vows. As stated in the New York Evening Mirror on November 14, 1844: “It is tampering with serious things, very dangerously, to circulate the three words ‘Mrs. John Smith,’one minute before the putting on of the irrevocable ring. The first proper use of the wedded name is to send it with parcels of wedding cake … to friends and persons desired as visiting acquaintances.”

Elizabeth and Effingham’s “at home” card may have been written as:

Mr. and Mrs. Effingham Nichols

at home

on the morning of Tuesday, Wednesday,

Thursday, and Friday next,

from 12 till 4.

361 Fourth St.

A popular tradition surrounding the boxed wedding cake called for an unmarried lady to sleep with the cake beneath her pillow on the night of the wedding. As a result her dreams would be “sweetened,” and she would be granted a vision of her future husband.

Wedding Gifts

At the time of Elizabeth and Effingham’s marriage, wedding gifts were usually bestowed only by the immediate family and very close friends of the couple. They were never of a practical nature (giving such gifts would be perceived as an insult, for it would imply need on the part of the receiver); in fact, they usually denoted a personal relationship with the bride and were often handmade. Typical gifts included shawls, clocks, fancy fans, richly ornamented thimbles, pictures, gold pencils, and gift books. Two popular books were The Bridal Keepsake, by Mrs. Coleman (1846), a collection of writings on religious and moral themes, and Austin’s Voice to the Married (1848), advertised as “The Best Bridal Gift.”

As the century progressed, it became more common to receive wedding gifts from relatives and friends. By the late-19th century, gift-giving became so profuse (a custom frequently renounced by preachers, etiquette manuals, and Godey’s Lady’s Book) that among the elite, special areas of the future bride’s home were set up to display the items; the bride-to-be would offer visiting hours to show off her silver and other acquisitions, which silently announced that her future prosperity was assured.

Silverware was always a gift to the bride, and thus was always engraved with the bride’s maiden name or initials; Elizabeth’s silver thus bears the mark “E.T.”

The “Bridal Cushion”

One popular wedding gift offered for sale by fancy dry-goods stores in the 1840s was the “bridal cushion.” Known as a Globe de Mariee in France, where the custom originated, it consisted of a tufted velvet cushion, usually red in color, that sat under a glass dome or globe decorated with gilt metal flora and fauna, as well as little mirrors. It was used to convey the love and hope brought to a marriage through meaningful objects accumulated by the couple throughout their lives. The bride would nestle her wedding mementos on the cushion; over the years she would add significant objects to the display. The cushion occupied pride of place in the Victorian parlor. Guests shopping for a bridal cushion for Elizabeth may have patronized Woodworth’s, located at 325 Broadway. In an advertisement on November 2, 1841, the shop offered “a new and beautiful collection of French Fancy Articles…which have been selected with great care by our tasteful agents in Paris.”

The Bridal Tour

The post-wedding trip, or bridal tour, taken by couples was an imitation of a ritual begun in 19th century England. Typically lasting one to two weeks, the journey served to as a means by which the pair traveled to visit friends and family who could not attend the wedding ceremony. Fashionable spots included Philadelphia, Washington D.C., as well as Niagara Falls and other natural wonders that were not too far from home. Overseas trips were largely unheard of. Couples were often accompanied by relatives or close friends. In the late 19th century the bridal tour became an exclusive, private trip for the newlyweds, and evolved into what we know of today as the traditional honeymoon.

Make Room for the Groom

As Charles Bristed mentioned in The Upper Ten Thousand: Sketches of American Society (1852): “It is the invariable custom that the young couple shall reside with the bride’s father for the first four or six months.”

Judging by the contemporary diaries of the period, very little advance preparation or thought was given to the groom’s move into his wife’s family home. In fact, like so many of the other wedding customs at this time, it was all rather last minute. On December 26, 1855, the day before his wedding, Edward Tailer wrote in his diary: “Mother assisted me in packing my trunk, and I am to send it over to Mr. Suffern’s [his father-in-law] after dark.”

And Henry Patterson wrote in his diary on July 21, 1844: “Wednesday forenoon [the day before the wedding] I sent my furniture, clothing, etc. to Mrs. Wright’s.

Bristed provided a hilarious description of the items his fictional groom brought to his bride’s home (earlier on the day of his wedding!):

“… seven coats and twelve pairs of trousers, and about thirty waistcoats, no end of linen, and carpet-bags full of boots, a gorgeous dressing-gown, and Turkish slippers, and smoking cap, and cigars numerous, and all sorts of paraphernalia generally, until the little dressing room adjoining the nuptial chamber is overflowing with foppery.”

Gaining A Son

After returning from their bridal tour, Effingham and Elizabeth took up residence in the Tredwell home on Fourth Street, and, in a decided departure from tradition, remained there for eleven years! (For a description of their married life, see the blog post of April 2017 “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing). Once settled at home, they commenced receiving congratulatory wedding calls from friends and acquaintances. In keeping with the custom of the time, Elizabeth may have worn her wedding dress, without the veil, for these visits.

Love’s Devotion

As Elizabeth and Effingham enter into the “divine” institution of marriage, let us imagine a lovely scene similar to the one described in the following poem, “Eras of Life: Marriage,” by Mrs. A.F. Law, which appeared in the January 1851 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book:

“One sacred oath hath tied

Our loves; one destiny our life shall guide;

Nor wild nor deep our common way divide!

Ushered thus, we haste to enter on a scene of radiant joy—

List’ning vows in ardor plighted, which alone can death destroy.

Passing fair the bride appeareth, in her robes of snowy white,

While the veil around her streameth, like a silvery halo’s light;

And amid her hair’s rich braidings rests the pearly orange bough,

With its fragrant blossoms pressing on her pure, unclouded brow.

Love’s devotion yields the future with young Hope’s resplendent beam;

And her spirit thrills with rapture, yielding to its blissful dream!”

Sources:

- Abell, L.G. Woman in Her Various Relations: Containing Practical Rules for American Families. New York: J.M. Fairchild & Co., 1855.

- Allen, Emily. “Culinary Exhibition: Victorian Wedding Cakes and Royal Spectacle.” Victorian Studies Vol. 45, No. 3 (Spring 2003), pp. 457-484. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3830185.

- Anonymous. The Art of Good Behavior, and Letter Writer, on Love, Courtship, and Marriage: A Complete Guide. New York: Huestis & Cozans, 1845. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society.

- Anonymous. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony. London: David Bogue, 1852. books.google.com. Accessed 1/18/18.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Tuesday, November 2, 1841, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/16/18.

- Bristed, Charles Astor. The Upper Ten Thousand; Sketches of American Society. London: John W. Parker and Son, 1852. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 2/13/18.

- The Evening Post. Friday, April 11, 1845, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/9/18.

- The Evening Post. Thursday, December 21, 1848, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 2/19/18.

- Godey’s Lady’s Book. Volume 42: January, 1851. www.hathitrust.org. Accessed 3/18/18.

- Hadden, John. Diary, 1841-1843. Rare Books and Manuscripts Division, New York Public Library.

- Lester, Mary H. Diary, 1847-1849. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Low, Harriet. Diary, 1844-45, Low Family Papers, 1750-1900. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- New York Daily Herald. Tuesday, March 26, 1844, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/6/18.

- New York Evening Mirror in the Buffalo Daily Gazette. Thursday, November 14, 1844, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 2/19/18.

- New York Tribune. Thursday, December 24, 1846, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/4/18.

- O’Neil, Patrick W. Tying the Knots: The Nationalization of Wedding Rituals in Antebellum America. Dissertation Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2009. www.cdr.lib.unc.edu. Accessed 3/15/18.

- Patterson, Henry. Diaries, 1832-1848. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Rothman, Ellen K. Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Tailer, Edward Neufville. Diaries, 1848-1917. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Thornwell, Emily. The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility: In Manners, Dress, and Conversation. New York: Derby & Jackson, 1856. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/17/18.

- Wallace, Carol McD. All Dressed in White: The Irresistible Rise of The American Wedding. New York: Penguin Books, 2004.

- Young, Leonard. A Short History of St. Bartholomew’s Church in the City of New York, 1835-1860. www.archive.org. Accessed 4/2/18.

The Wedding “Whirl and Vortex:” Mid-19th Century Wedding Preparations

by Ann Haddad

This is the third in a series of blog posts on mid-19th century courtship and wedding customs. Click for Part One, on 19th century Courtship, and Part Two, on Marriage Proposals and Engagements.

High Spirits at the Tredwells

Imagine the excitement in the family room of the Tredwell home on a spring evening in late March, 1845. Elizabeth, the eldest daughter of Seabury and Eliza Tredwell, had just named Wednesday, April 9, as the date of her wedding to Effingham Nichols. One can picture Elizabeth and her betrothed, perhaps along with her mother, Eliza, and her sister Mary, seated around the table in the family room, composing the guest list and writing out the wedding invitations. The wedding was only two weeks away, and so much needed to be done! The Tredwell family was about to leap head-on into what one contemporary etiquette manual referred to as “the whirl and vortex” of a wedding. This post will address three important aspects of mid-19th century wedding planning: invitations, the trousseau, and the duties of the groom.

The Transformation of the American Wedding

Elizabeth and Effingham were married in 1845, at a time when the form of the American wedding was gradually transitioning from a simple, family-centered, informal celebration to an elaborate, public, and expensive spectacle. We have no record of their wedding, so it is impossible to know the location, format, or style of their festivities. Seabury, however, given his wealth and social status, could afford to give his eldest and first-wed daughter an elaborate wedding with all the trimmings.

What Wedding Industry?

Up until the mid-19th century, the “wedding industry” (as the providers of services and goods for weddings are collectively known today), barely existed. Because a home wedding was the standard, and the bride’s family hosted the reception, gatherings were usually small and intimate. Many of the items in the bride’s trousseau were made by hand by family members, and the wedding dress was usually the work of a reputable dressmaker known to the family. New York City newspapers from the 1840s featured no advertisements for dedicated commercial wedding “vendors,” or professionals who furnish the trappings of an elaborate wedding. Whereas florists, jewelers, confectioners, and dry goods stores existed, very few items, save for wedding attire, were marketed with a specific eye to wedding celebrations.

This would all change in the late 1850s and especially after the Civil War, as the wedding industry became a huge commercial enterprise, and wedding rituals, especially among upper class families, became more formal, public, and elaborate. Businesses sprang up to cater to the needs of the bride-to-be, including stores that offered ready-to-wear bridal dresses and complete trousseaus. Women were faced with many more choices to consider in every aspect of their wedding, and therefore required more time to shop and plan. Moving the ceremony from the home to a church, along with, some years later, the option of holding the reception in a grand hotel, meant that many more guests could be accommodated; hence, guest lists grew accordingly.

Such Short Notice!

According to wedding etiquette manuals and contemporary diaries, in the first half of the nineteenth century wedding invitations were sent out anywhere from four days to two weeks prior to the wedding date. This short span of time between the date of the invitation and the actual wedding date reflects the simplicity of the wedding form and the minimal advance planning it necessitated.

For example, on Saturday, December 11, 1847, just eight days before her wedding to Andrew Lester, Mary Harris wrote in her diary: “… we were very much engaged in preparing the invitations to be sent next Monday if nothing happens.”

In a letter dated November 1, 1854, from Phebe Tredwell to her sisters (who were at the family summer home in Rumson, New Jersey), she stated: “Shortly after you left on Saturday we received an invitation to Caroline Quackenbush’s wedding next Wednesday from 1 to 3.”

And on November 24, 1855, one month before his marriage to Agnes Suffern, Edward Tailer wrote in his diary: “It will soon be time for us to spend several evenings in directing the invitations.”

The Tredwell/Nichols Guest List

We know neither the size of the guest list for Elizabeth and Effingham’s wedding, nor the names of those invited. Both the Tredwell and Nichols families were wealthy and prominent members of elite New York society. Both had large extended families; Seabury had many former business associates; Effingham had colleagues; and undoubtedly both families had a large circle of friends. So chances are the guest list was long, especially since the Tredwells could accommodate a large gathering in their Greek Revival double parlors, and guests were accustomed to having to cram into the indoor spaces for the festivities.

The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852) warns, however, that any friends denied an invitation to the reception, because of lack of sufficient space, should not feel affronted. Rather, “It is considered a matter of friendly attention to those who cannot be invited, to be present at the ceremony in the church.”

A Sociable, or a Wedding?

Wedding invitations were hand written, in the same style as an invitation to a sociable (the 19th century term for a social gathering). The invitation usually did not announce that a wedding was to be celebrated. This speaks to the rather informal approach taken to the wedding itself, and the fact that most weddings were held in the home of the bride’s parents. So how did guests know to expect nuptials? For one thing, relatives and friends knew of the couple’s engagement, which had gone on for several months at the very least. And once the date had been set by the bride-to-be, both hers and the groom’s families shared the details within their circles by word-of-mouth. In that sense, the written invitation was a formality. In an article on New York fashion in the Buffalo Daily Courier from 1849, a gentleman commented on the speed with which news of a wedding date got around: “It is known in an hour from Union Square to the Battery.”

| .. |

In an 1844 article in the New York Daily Herald, one observant young friend of a future bride detected something in the air:

“For several days previous, the bright and happy faces of the fair ones told me that the gala night was nigh at hand. At length all doubt was removed, when a note of invitation was left at my address, stating that Miss B— would be at home on Wednesday evening, January 3rd; and then I knew that the bridal of one of our fairest maidens was to take place.”

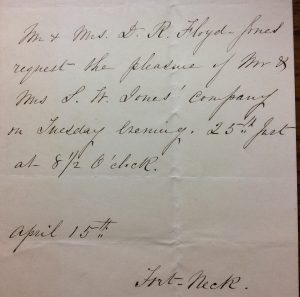

Etiquette dictated that the wedding invitation include only the name of the bride’s parents, the date and the time. In the invitation pictured at left, written on April 15, 1854, for an April 25 wedding, no mention of a wedding is made:

“Mr. And Mrs. D.R. Floyd-Jones request the pleasure of Mr. and Mrs. L.W. Jones’ company on Tuesday evening, 25th just at 8 1/2 o’clock.

April 15th

Fort-Neck”

As the bride was married at her parents’ home, mentioning that a wedding was to take place was deemed unnecessary. Note the evening hour, 8:30 p.m., which was typical for a home wedding.

A church wedding, on the other hand, usually took place in the morning. According to The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness (1860):

“In this case [weddings at church], none are invited to the ceremony excepting the family …”

Additional guests were invited to the reception, held at the bride’s parents’ home following the church ceremony. If Elizabeth and Effingham were married at church, their wedding invitation may have read as follows:

“Mr. and Mrs. Seabury Tredwell

request the pleasure of Mr. and Mrs. Jones’ company,

on Wednesday morning next, at eleven o’clock,

361 Fourth Street [the house number in 1845]

Thursday, April 2nd”

All Those Penmanship Drills Pay Off

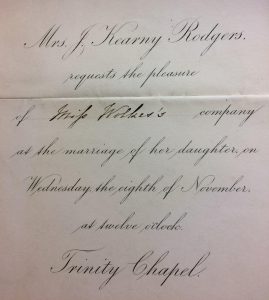

In the 1840s, wedding invitations were hand written in a fancy cursive script on white card stock. This was hardly a challenge for well-educated young ladies; excellent penmanship was considered an essential requirement for completion of finishing school. Engraved and printed invitations did not become popular until the early 1860s; ten years later, in keeping with the formality and grandeur of the wedding itself, and more practical given the longer guest lists, such mass produced invitations became de rigueur. Note the engraved invitation (pictured at right) to the 1865 wedding of the daughter of Mrs. J. Kearny Rodgers at Trinity Chapel. Despite the formality of the style, the bride-to-be’s name is not mentioned. One assumes that Mrs. Rodgers had only one daughter!

The Bridal Trousseau

The custom of a bridal trousseau, i.e. the clothing and “soft goods” (such as bed and table linens) that a bride brought to her marriage, became increasingly popular in the mid-19th century. The size of a trousseau depended on the family’s wealth and the position the couple would be assuming in society. For Elizabeth, as the wife of a well-to-do attorney who no doubt had many social obligations, a proper trousseau consisted of a lady’s complete wardrobe (including the wedding gown) sufficient for at least an entire year. This elaborate trousseau assemblage undoubtedly occupied most of Elizabeth’s time prior to her wedding.

According to The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, Fashion, and Manual of Politeness:

“In preparing a bridal outfit, it is best to furnish the wardrobe for at least two years, in under-clothes, and one year in dresses, though the bonnet and cloak, suitable for the coming season, are all that is necessary, as the fashions in these articles change so rapidly.”

Shop ’Til You Drop

Elizabeth no doubt received a sum of money from her father with which to purchase her trousseau. It is impossible to know the cost of a trousseau in 1845, as it varied depending on the family’s social status and financial resources. In 1850, Godey’s Lady’s Book estimated that the cost of the wedding dress and veil alone to be $650. Add to that all the other complements of the trousseau, and one may safely assume that the amount spent on a trousseau by a wealthy family like the Tredwells would be upwards of $1,000 (approximately $30,000 today).

Upon the announcement of her engagement, Elizabeth, assisted by her mother, sisters, and close friends, likely commenced sewing many of the personal items included in the trousseau, such as petticoats, corset covers, nightgowns, dress sleeves, and handkerchiefs. Once her wedding date was set, the shopping began with a vengeance at popular dry-goods stores, such as A.T. Stewart, then located on Broadway near Chambers Street, and Lord and Taylor, then located on Catherine Street. These emporiums stocked many trousseau items in addition to dresses, such as sewing implements, linens, shawls, slippers, and hair combs and brushes.

In the short story Incompatibility of Temper, by Alice B. Haven, published in the January 1862 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book, the author describes how the bride’s trousseau has taken over one bedroom:

“The best bedroom was draped with the new dresses that had been made up with much thought and consultation of the fashion magazines; the clothes-press was entirely occupied by the wedding dress itself, over which a sheet was carefully hung to protect it from all possible contact with dust or flies; and Marie’s own drawers were overflowing with the four dozen cotton and two dozen linen, to say nothing of nightcaps, which were at least happily completed. There were twenty things to be done yet …”

The Most Important Item of a Trousseau: the Wedding Dress

According to the August 1849 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book, the “etiquette of trousseau” dictated that a fashionable wedding dress be made of white silk or satin, with a Brussels lace over-dress with a fitted bodice and full skirt. A white veil, long and full, and most likely made of Brussels lace, was attached to an artificial wreath of orange blooms (popularized by Queen Victoria, who wore them at her wedding in 1840) that encircled the head. Flat white satin or silk slippers decorated with ribbons; white silk stockings; short white kid gloves; and an embroidered handkerchief (perhaps with interlaced initials of the bride and groom), completed the ensemble.

According to etiquette manuals such as The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility (1846), jewelry was practically forbidden: “She should wear no ornaments but what her intended or father should present her for the occasion.”

In a letter sent by a “Sarah” from Manhasset, Long Island to Ida A. Coles, dated April 18, 1847, she wrote:

“She [the bride] has ten new dresses and some of them are very handsome. The wedding dress is white satin with an embroidered lace over, it is beautiful. She has not purchased her veil as yet.”

Dressmaker Required

Eliza Tredwell most likely hired a dressmaker to create Elizabeth’s wedding ensemble. The seamstress may have lived with the family for a few weeks before the wedding, sewing the dresses in return for room and board, or for a set fee. Imagine the excitement with which Elizabeth and her mother examined the latest silk and satin fabrics, imported from France and widely available at the many dry-good stores that catered to ladies’ fashions, such as H. Myers & Gedney, located at 375 Broadway.

Elizabeth’s fine white bridal slippers may have come from J.B. Miller’s shoe store, located at 142 Canal Street, which in 1844 advertised “White and Black satin, also french, Morocco and Kid slippers, for Balls, Parties, Weddings, &c.”

Ready-to-wear bridal dresses were not widely available in stores until the 1860s, but the earliest advertisements for “wedding dresses,” as distinct from dresses for other occasions, and made in France, appeared in New York newspapers by the mid-1840s. One enterprising woman was selling them in 1844, according to an advertisement in the New York Daily Herald:

“Madame N. Scheltema informs her customers … that she has just received per last Havre packet, a new and splendid assortment of rich embroidered and other Wedding Dresses.”

James Beck & Co., and William A. Smets, two dry-goods stores located on Broadway, advertised “Wedding and Soiree Dresses.” Shops like these, however, no doubt catered to the wealthy upper class, who could afford the fine items sold there. The Tredwell family probably patronized these establishments.

Dressing the Rest of the Family

One can only imagine Eliza’s state of mind in the weeks before her daughter’s wedding. Not only did she have to oversee Elizabeth’s trousseau and all it entailed, she was also faced with the daunting task of dressing herself and her FIVE other daughters! There were new ensembles to be purchased (white dresses for those sisters chosen to be bridesmaids); and a hairdresser to be engaged for Eliza, Elizabeth, and perhaps Elizabeth’s sister Mary (who at 20 was considered a young lady). Her wealth would have allowed Eliza to hire a dresser to assist the women with their toilettes.

Eliza also bore the responsibility of making sure that Elizabeth’s younger brothers Horace and Samuel (ages 21 and 18, respectively), were properly attired. Whether or not they were groomsmen, because of their age their outfits would have been very similar to Effingham’s (described below).

Mrs. Abiel Abbot Low, a wealthy woman who lived in Brooklyn Heights, recorded in her diary the extensive preparations for the wedding of a family member, to be held on Sunday, February 2, 1845 (just two months before Elizabeth’s wedding). She made frequent trips by coach back and forth from her home in Brooklyn to Manhattan for this purpose. On Thursday January 23, 1845, she wrote: “I selected a superb silk dress at Stewart’s to wear to Josiah’s wedding.”

Several days later, on Thursday January 30, she noted: “I went to New York to engage Martelle to dress my hair for the wedding, but he was engaged for the time that I needed him. I bought a pretty evening fan …”

What Does Effingham Do?

Compared to Elizabeth’s multiple wedding chores, Effingham had relatively little to do. As his father, the Reverend Samuel Nichols, was to perform the wedding ceremony, it spared him the headache of having to track down an available rector, as Henry Patterson indicated in his diary on July 14, 1844, one week before his wedding:

“I made an engagement with Mr. Edwin Hatfield pastor of the Presbyterian Church, corner of Broome and Ridge Street, to perform the marriage ceremony for us, next Thursday evening at eight o’clock. I endeavored to get Mr. Bellows or Mr. Dewey, but they are both absent from the city.”

Custom dictated that the groom was also responsible for finding a suitable home for his bride. Effingham was spared this task, however; after the wedding and travel (if any) he simply joined his bride at the Tredwell home on Fourth Street. It was not atypical for newlyweds to live with family, which gave a man time to establish himself in business before buying a home.

If a “wedding tour” (as it is called in The Art of Good Behavior) was planned for after the marriage, Effingham made the arrangements, including clearing his work schedule for anywhere from two weeks to one month to accommodate his absence.

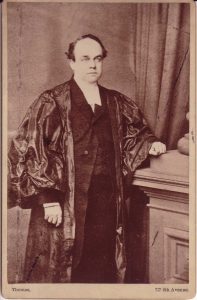

Effingham Gets Dressed Up, Too

Men’s fashion in the 1840s was characterized by low, tightly cinched waists; snug waistcoats and trousers; high collared shirts tied with a cravat; and flared frock-coats. The groom’s attire is described in The Art of Good Behavior:

“The bridegroom must be in full dress, black or blue dress coat, which may be faced with white satin; a white vest, black pantaloons, and dress boots, or pumps, with black silk stockings, and white kid gloves, and a white cravat. The groomsmen should be dressed in a similar manner.”

In the 1840s, a colorful, embroidered waistcoat was a fashionable item in a groom’s attire. The waistcoat was occasionally worked by the bride, and presented as a wedding gift to the groom. Elizabeth may have shopped at William T. Jennings on Broadway, which advertised in 1844, “a lot of rich silk and satin vestings, suitable for ball and wedding vests,” for material for Effingham’s waistcoat.

Destroy the Evidence!

The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony also strongly recommended that a gentleman begin his marriage with a clean moral slate, by divesting himself of certain bachelor friends whose company would not be deemed fitting for a newly married gentleman. Burning one’s bachelor letters is also considered essential, for: “Not to do this might hereafter lead to inconvenience.”

Not a Whisker Out of Place

One other concern may have occupied Effingham’s mind before the wedding. If he sported whiskers, they must be neat and full by his wedding day. So, he may have followed the lead of Henry Patterson, who on Sunday, May 19, 1844, approximately two months before his wedding, wrote in his diary: “I cut off my whiskers, intending immediately to let them grow again, so as to have a new sett [sic] on my wedding day.”

With This Ring I Thee Wed

The task that probably had the greatest significance for Effingham was purchasing Elizabeth’s wedding ring. The fashion for wedding bands was plain, thick gold. Although jewelry store advertisements were plentiful in newspapers in 1845, only one, William Wise, located at 79 Fulton Street in Brooklyn, offered “gold wedding rings” for sale. To ensure that the ring was properly sized for his bride, according to the Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony, the man must: “… get a sister of your fair one to lend you one of the lady’s rings.” One can just picture Effingham convincing Mary to secretly remove a ring from Elizabeth’s jewelry box!

In the poem “The Bridal” (1849), which one may imagine had been written with Elizabeth and her sisters in mind, one finds reference to the wedding ring:

“Oh! They are blest indeed, and swift the hours

Till her young sisters wreathe her hair in flowers.

Then before all they stand; the holy vow,

And ring of gold—no fond illusion now—

Bind her as his.”

Stay tuned: the next blog post will cover the wedding day!

|

Sources:

- Anonymous. The Art of Good Behavior, and Letter Writer, on Love, Courtship, and Marriage: A Complete Guide. New York: Huestis & Cozans, 1845. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society.

- Anonymous. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony. London: David Bogue, 1852. books.google.com. Accessed 1/18/18.

- Bradford, Isabella. “A Fashion Worth Revisiting? A Bridegroom’s Embroidered Wedding Waistcoat, 1842.” Two Nerdy History Girls. Tuesday, November 11, 2014. www.twonerdyhistorygirls.blogspot.com. Accessed 4/4/18.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Wednesday, March 5, 1845, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/6/18.

- Coles Family Papers, 1803-1859. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- David R. and Mary Floyd-Jones Invitation, 1854 April 15, Floyd-Jones Papers. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Emily Hosack Rodgers Collection, 1848-1888. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- “Etiquette of Trousseau.” Godey’s Lady’s Book. August, 1849.

- The Evening Post. Tuesday, 16 January, 1844, p. 3. www.nespapers.com. Accessed 3/6/18.

- The Evening Post. Friday, 26 January, 1844, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/13/18.

- The Evening Post. Friday, 6 September, 1844, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/6/18.

- The Evening Post. Saturday, November 16, 1844, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/21/18.

- The Evening Post, Monday, 10 March, 1845, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/30/18.

- Hartley, Florence. The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, Fashion, & Manual of Politeness. Boston: G.W. Cottrell, 1860. www.gutenberg.org. Accessed 3/15/18.

- Haven, Alice B. “Incompatibility of Temper.” Godey’s Lady’s Book. January, 1862.

- Lester, Mary H. Diary, 1847-1849. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Low, Harriet. Diary, 1844-45, Low Family Papers, 1750-1900. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- New York Daily Herald. Tuesday, 27 February, 1844, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/13/18.

- New York Daily Herald. Saturday, May 18, 1844, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/11/18.

- New York Daily Herald. Thursday, April 24, 1845, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/16/18.

- “New York Fashions.” Buffalo Daily Courier. Monday, 5 November, 1849, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/18/18.

- New York Tribune. Saturday, 28 December, 1844, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/7/18.

- O’Neil, Patrick W. Tying the Knots: The Nationalization of Wedding Rituals in Antebellum America. Dissertation Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2009. www.cdr.lib.unc.edu. Accessed 3/15/18.

- Patterson, Henry. Diaries, 1832-1848. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Pinckney, Cotesworth, ed. The Wedding Gift, To All Who are Entering the Marriage State. Lowell: Milton Bonney, 1849. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 4/5/18.

- Reeves, Emma. History of the Bridal Trousseau. September 15, 2016. www.theribboninmyjournal.com. Accessed 3/18/18.

- Rothman, Ellen K. Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Tailer, Edward Neufville. Diaries, 1848-1917. Manuscripts Division, New York-Historical Society.

- Thornwell, Emily. The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility: In Manners, Dress, and Conversation. New York: Derby & Jackson, 1856. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/17/18.

- Tredwell, Phebe. Letter, November 1, 1854. Nichols Family Papers. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “History of Fashion 1840-1900.” www.vam.ac.uk. Accessed 4/4/18.

- Wallace, Carol McD. All Dressed in White: The Irresistible Rise of The American Wedding. New York: Penguin Books, 2004.

- “Wedding Memories: The Bride’s Trousseau.” Magpie Wedding. www.magpiewedding.com. Accessed 4/9/18.

Mine and Mine Only: The Marriage Proposal and Engagement

by Ann Haddad

This is the second in a series of blog posts on mid-19th century courtship and wedding customs. Click here to read the first post, on 19th century courtship.

A Horse and a Wife

Charles A. Bristed, in his satirical sketch of American society, The Upper Ten Thousand (1852), noted:

“The first thing, as a general rule, that a young Gothamite does is to get a horse; the second, to get a wife.”

Although it is uncertain if Effingham Nichols owned a horse, he did indeed acquire a wife, the bride being none other than Elizabeth Tredwell, eldest daughter of Seabury and Eliza Tredwell. Effingham was only two years into his law practice, located on 7 Nassau Street, when he wed the very eligible 23-year-old Elizabeth on April 9, 1845. We do not know the duration of their courtship, but Effingham must have received significant encouragement from the young lady during that time, emboldening him to declare his love and to propose marriage.

Never Flirt!

Asking a young woman for her hand in marriage was never perceived as an easy task for a gentleman. After all, his fate rested in her hands! For this reason, the etiquette manuals of the day warned women repeatedly not to trifle with a young man’s affections, lest it earn the woman the dreaded reputation of being a flirt. If a gentleman’s behavior towards a woman conveyed romantic feelings, and she did not wish to encourage him, she was to do her utmost to gently rebuff his sentiments in a kindly manner, and gradually withdraw from his company. An honorable woman never shared (except with her parents) that she had rejected a suitor. As A Manual of Etiquette (1868) stated:

“If you possess either a decent generosity, or the least good breeding, you will not divulge a secret which should be sacred between you.”

Passing the Test

| … |

After their courtship had gone on for an appropriate period (etiquette manuals were reluctant to establish the proper length of the courtship period), a woman who found the attention from her suitor more than agreeable indicated in unspoken ways that a proposal of marriage would be welcome. She, of course, could not propose to a gentleman (only queens were permitted to do so; Queen Victoria notably proposed to Prince Albert); but, according to the Dictionary of Love (1858):

“… she may lawfully do all in her power to put him in the notion of proposing. She may be very glad to see him when he calls, she may gently chide him for staying away so long ‘We feared you had forgotten us,’ or she may, by the purest accident, always happen to get a seat very near him whenever she is in his company. It is clearly a lady’s right to modestly open the way for the approaches of a gentleman whose heart she honorably wishes to obtain.”

A young lady’s father (especially a wealthy one like Seabury Tredwell, who needed to protect his daughter from fortune hunters) had already assessed the suitor’s finances (were his prospects good enough to provide a home for and support a wife and children?), scrutinized his lineage (did he come from a reputable family?), and deemed him acceptable. At this point, it was safe and indeed incumbent on the young man to seize the opportunity and proceed with a proposal. As stated in The Art of Good Behavior (1846), a popular etiquette manual:

“As a general rule, a gentleman need never be refused. Every woman, except a heartless coquette, finds the means of discouraging a man whom she does not intend to have, before the matter comes to the point of a declaration.”

An unidentified young clerk in New York City indicated his confidence that he had a future with his beloved Julia when he wrote in his diary on October 13, 1844:

“Was much amused at a remark Julia made. She said ‘I don’t know how to take you.’ I replied ‘Take me as I am.’ She answered, ‘I expect I shall be obliged to.’ It may be a prophetic remark.”

Once the suitor determined that his offer of marriage would be welcomed, there was nothing left to do but “pop the question” (an idiom in use since 1826). The Art of Good Behavior perfectly captured the anxiety of the moment:

“… and though he may tremble, and feel his pulses throbbing and tingling through every limb; though his heart is filling up in his throat, and his tongue cleaves to the roof of his mouth, yet the awful question must be asked.”

Will You Marry Me?

Should a gentleman find elusive the right words with which to propose, he needed only consult one of the popular etiquette manuals, which offered many suggestions. Here are some from The Art of Good Behavior:

“Will you tell me what I most wish to know!”

“Yes, if I can.”

“The happy day when we shall be married?”

“Have you any objection to change your name?” “How would mine suit you?”

“One word from you would make me the happiest man in the universe.”

“Well, Mary, when is the happy day?” “What day, pray?” “Why, everybody knows we are going to get married, and it might as well be one time or another; so, when shall it be?”

And then there was the laconic gentleman who, according to the Evening Post of August 14, 1840, proposed in the following manner:

“Pray, madam, do you like buttered toast?” “Yes, sir.” “Buttered on both sides?” “Yes, sir.” “Will you marry me?”

The joyous declaration of love was described in the Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852):

“The happy moment of opportunity arrives, in sweet suddenness, when the flood gates of feeling are loosened, and the full tide of mutual affection gushes forth uncontrolled.”

James R. Burtin, a young New York gentleman who worked as an engraver, recorded in his diary the exciting moment when, after nearly two years of courtship, he proposed to his beloved Ann Elisa on February 18, 1844:

“This is an evening I shall always remember with mingled feelings of pleasure and pain. One question I asked my dear Ann, the answer of which depended my future happiness or misery and she hesitated to answer it. It was a moment of suspense tho if she knew how I loved her and how dear she is to me she would have given me an answer at once. I did not doubt but that her answer would be such as one as I wish and the answer was one that put all doubt aside. She loves truly and I love her and whatever may take place I shall love her as long as life shall last. She is dearer to me than Mother, brother or Sister. Without her I may almost say that life would be unendurable, but now all doubts are at an end. She is mine and mine only.”

Put It in Writing

For those timid, tongue-tied gentlemen who could not bear the thought of proposing in person, etiquette manuals, such as the American Fashionable Letter Writer (1845), also offered sample proposal letters, such as:

“Every one of those qualities in you which claim my admiration, increased my diffidence, by showing the great risk I run in venturing, perhaps before my affectionate assiduities have made the desired impression upon your mind, to make a declaration of the ardent passion I have long since felt for you.”

On October 28, 1843, Henry Patterson, a contemporary of Burtin’s, wrote in his diary about his written proposal of marriage to Eleanor Wright:

“Last week Thursday I made proposals of marriage to her in writing; Sunday evening I received a conditional acceptance, also in writing, and Wednesday evening we spent in unfolding to each other our situation, prospects, hopes, principles, feelings, in short everything which would tend to a judicious and proper settlement of the question now the subject of our joint consideration. I will only record, that as I become acquainted with her, I become more thoroughly convinced of our suitableness to each other; and the outpouring of tender feelings which I enjoyed on Wednesday evening, that sensation of mutual love and trust which I have since felt within us, renders the present the happiest period of my life.”

| … |

I’ll Get Back to You

When a gentleman made an offer of marriage either in person or by letter, it was incumbent upon the young lady to receive it graciously. She knew, either by instruction from her parents or by the advice provided by etiquette manuals, never to accept or reject the offer immediately. Such an important decision merited deep reflection, and discussion with her parents, whose consent was necessary before any answer was given. As Farrar reminds her readers in The Young Lady’s Friend (1837):

“It should be an avowed principle of your life, that you will never marry without the consent of your parents, nor merely to please them.”

If the young lady’s parents opposed the match, the couple carefully considered the objection, and perhaps delayed their marriage until the reason for the disapproval had been overcome.

The American Fashionable Letter Writer provided an example of a young lady’s written reply to a proposal of marriage:

“There are many points beside mere personal regard to be considered; these I must refer to the superior knowledge of my father and brother, and if the result of their inquiries is such as my presentiments suggest, I have no doubt my happiness will be attended to by a permission to decide for myself.”

Man to Man

After proposing marriage, the next daunting step for the gentleman was a formal meeting with the woman’s father, to officially ask for his consent to the marriage. It is noteworthy, with regard to parental consent, that the opinion of the young woman’s parents appears to be the only one that matters. None of the diaries consulted for this post made any mention of the suitor’s parents in any aspect of the courtship or engagement. As Ellen K. Rothman concluded in Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America (1984), “A woman’s parents were asked; a man’s parents were told.”

Seabury Tredwell was probably not surprised when Effingham Nichols entered his study to request Elizabeth’s hand in marriage; he most likely was expecting it. Effingham would have been prepared to discuss his law practice, his future prospects, and his financial situation in detail. He was, after all, responsible for providing a stable economic environment for Seabury’s daughter; it was critical that he explain how he planned to go about this. Seabury already knew Effingham came from an excellent family, and must have been willing to accept Effingham’s status and envision his future success. Imagine the joyful scene on Fourth Street when, once Seabury gave the couple his blessing, Elizabeth and Effingham shared the happy news with her mother, Eliza, and her siblings!

The parents of Eleanor Wright, the young woman with whom Henry Patterson was in love, were separated (separation and divorce were not as uncommon as we might think — a topic for a future blog post). That may explain why it took two months for Henry to meet with her father. On December 30, 1843, he wrote:

“By mutual agreement that it was advisable, I called the next morning on her Father, in Fifth Street, and briefly acquainted him with my past intercourse with his daughter and my plans for the future; I asked his approval. He expressed his approbation as far as he was acquainted with the circumstances, and treated me in every respect in a gentlemanly manner.”

We have no idea what Elizabeth’s siblings thought of her suitor, Effingham Nichols. The opinion of brothers and sisters held little weight when it came to choosing a mate for life. Elizabeth Brevoort was a young girl of fourteen when on July 31, 1848, she wrote in her diary of her sister’s love interest:

“I must say it is not the marriage I wish for her but if she thinks she will be happy with him, I am sure it is none of my business.”

The Engagement Period

Patrick W. O’Neil, in his dissertation thesis, Tying the Knots: The Nationalization of Wedding Rituals in Antebellum America (2009), described the engagement period (which typically lasted from six months to two years, depending on the family circumstances and the age of the couple) as a moment of transition between courtship and married life wherein couples could come to a full understanding of the meaning behind their commitment to one another. It was viewed as an opportunity for the lovers to imagine themselves married, and to declare their suitability to the world. In doing so, they experienced a loosening to some extent of the restrictive bonds of decorum, and hence were able to deepen their knowledge of each other. O’Neil cautioned, however, that the easing of rules in this rigid society only went so far:

“None of this is to say that the middle-class men pursued gender equality in their married relationships: they would not have taken kindly to assertions of autonomy from their future wives.”

In the mid-19th century, once the young lady and her parents consented to the marriage, the announcement of the engagement was initially made to family and intimate friends only; this was typically done in writing. This allowed all involved to take a collective breath and live with the idea; it would be during this time that either party could gracefully break off the engagement without doing widespread damage. After a week or two, the wider circle of friends and acquaintances would receive news of the engagement.

The Ring-Bearers

According to Ellen Rothman, in Hands and Hearts, the custom of presenting one’s betrothed with a ring upon engagement began in the 1840s. The simple bands, which sometimes included a cut stone, were mutually exchanged; they served as a public sign of the couple’s commitment to each other. Occasionally, another personal token, such as a portrait miniature of the future bride, was presented to the groom-to-be in place of a ring. Diamond engagement rings as we know them today did not become popular until Tiffany & Co. introduced the Tiffany setting in 1886.

Behave Yourselves

Not surprisingly, the conduct of a betrothed couple was also governed by a strict protocol. When in public, any overt signs of familiarity and exclusivity were forbidden. The gentleman was to behave gallantly and honorably toward any woman in his presence, not just to his fiancée; and his future bride refrain from pouting or reacting with jealousy and anger when he did so. That didn’t mean, however, that the gentleman refrained from being protective of his sweetheart, or that she ignored him. Ideally, they presented to the world an image of blissful and contented happiness. Although the couple did not isolate themselves from the society of others, the woman was careful to avoid spending time with any other man in private. When attending sociables and other entertainments in the absence of her betrothed, etiquette dictated that she be accompanied by a family member or intimate family friend.

In private, a gentleman never took advantage of his bride-to-be, for he had her honor to maintain. As the Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852) pointed out: “he is dealing with his future wife.” Whenever he was in the presence of his betrothed, it was a young man’s duty to avoid any display of fatigue, low spirits, or “excessive animation.” Several etiquette manuals also discussed the engagement period as a time when a gentleman bore the responsibility of advising and guiding his betrothed, by correcting her faults and helping to mold her character. It was the rare mid-19th century treatise, such as Mrs. A.J. Graves’ Woman in America (1858) that challenged this notion, stating, “woman was not given to a man for a toy to amuse his idle hours; but to be, in truth and in reality, a helpmate to him – a minister for good.”

The Welcome Mat

Once the engagement was underway, the gentleman was expected to pay frequent calls at his bride-to-be’s home. He was to ascertain, however, the time most convenient for his call; and when he visited, he was to focus attention on the entire family, not just on his betrothed. His aim in making the calls was to gradually win the affection of the family, especially the girl’s mother. The visits were usually made in the evening, with the gentleman wearing evening attire, as he would for the theatre or a concert. As the Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony stated,

“The neglect of this point would betray, first, a carelessness in habits, next, a want of deference to the lady’s family, and lastly, a deficiency in due respect to herself.”

According to their diary entries, both Henry Patterson and James Burtin could be found almost nightly at the homes of their betrothed. Often they had tea with the family in the afternoon and then return in the evening! Burtin, who had made a habit of frequent visits even before his engagement, wrote in his diary on November 16, 1843:

“I am inclined to think that love makes a fool of a man , that is in other people’s estimation, but what is the use. I love Ann Elisa and when I can see her there is not the least doubt but that I will.”

| .. |

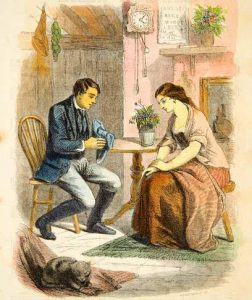

Stealing a Kiss

Despite the protocol set forth in popular etiquette manuals, evidence in diaries of this period indicates that betrothed couples were frequently left alone in the young lady’s home, often until 1 or 2 a.m. Henry Patterson and Eleanor Wright spent many evenings alone in her parlor, playing chess, whist, reading to one another, and ultimately exchanging mutual affection. On January 21, 1844, he wrote:

“Monday evening I spent with Eleanor, with chess, reading, and conversation, all of which, having mingled with them expressions of the most tender love and kindest feelings, served to render that evening one of the happiest seasons of my life.”

James Burtin even exercised with Ann Elisa, as he wrote on his diary on May 25, 1843:

“In the evening called over to see Ann Elisa found her jumping the rope joined in with her and had some fine exercise but found it rather warm work.

“This is a Waste of Our Time”

Once betrothed, couples were permitted to go out together unaccompanied: for walks on the Battery; to concerts at Niblo’s Garden; to museums, theatre, church, lectures, and to weddings of friends and family. After months of such activity, with no wedding date yet set, Henry Patterson was growing increasingly frustrated. He wrote in his diary on March 24, 1844:

“Oh! how tired and impatient I feel, to be thus compelled to take a part in amusements, and join in company for which I feel no affinity. Enjoying alone Eleanor’s society, with no restraints on the interchange of tokens of love, is almost the only thing that is at all satisfactory to me: how painful to me that this is a waste of our time, in foolery, and empty amusements. Yet, may it not be played upon us to exercise our patience, and and learn us to prize more highly and justly the unspeakable blessing which we do enjoy?”

Fixing the Day

The days of idle amusements were soon over for Henry and Eleanor; once their marriage date was set (by the woman, this being one of her express privileges), they found themselves busier than ever. There was a household to set up, a trousseau to purchase, and a wedding to arrange. As the wedding industry was in its infancy, it was typical for a wedding date to be announced only two to three weeks prior to the actual date. As a result, the wedding preparations were intense and extensive, requiring hard work by both parties. The burden, as we shall see, rested more on the woman’s shoulders, for as Rothman points out in Hands and Hearts: “While engagement interfered with a man’s work, it was a woman’s work.”

Sources:

- Anonymous. The American Fashionable Letter Writer, Original and Selected. Troy, N.Y.: W. & H. Merriam, 1845. www.catalog.hathitrust.org. Accessed 3/1/18.

- Anonymous. The Art of Good Behavior, and Letter Writer, on Love, Courtship, and Marriage: A Complete Guide. New York: Huestis & Cozans, 1845. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society.

- Anonymous. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony: With A Complete Guide to the Forms of a Wedding. London: David Bogue, 1852. www.books.google.com. Accessed 2/2/18.

- Arthur, T[imothy]S[hay]. Advice to Young Ladies on Their Duties and Conduct in Life. Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1847. babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 1/16/18.

- Brevoort, Elizabeth. Diary, 1848. Rare Books and Manuscripts Division, New York Public Library.

- Bristed, Charles Astor. The Upper Ten Thousand; Sketches of American Society. London: Parker and son, 1852. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 2/13/18.

- Diary of an Unidentified Clerk in New York City, 1844-45. MssCol. 2147, Rare Books and and Manuscripts Division, New York Public Library.

- Diary of an Unidentified Young Man [James R. Burtin], January 1, 1843- 1844. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Farrar, Mrs. John. A Young Lady’s Friend. Boston: American Stationers’ Company, 1838. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/23/18.

- Graves, Mrs. A.J. Woman in America; Being an Examination into the Moral and Intellectual Condition of American Female Society. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1858. www.catalog.hathitrust.org. Accessed 3/2/18.

- Johnson, S. O. [Sophia Orne]. A Manual of Etiquette with Hints on Politeness and Good Breeding. Philadelphia: D. McKay, 1868. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/26/18.

- O’Neil, Patrick W. Tying the Knots: The Nationalization of Wedding Rituals in Antebellum America. Dissertation Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2009. www.cdr.lib.unc.edu. Accessed 3/1/18.

- Patterson, Henry. Diaries, 1832-1848. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- “Popping the Question.” The Evening Post, Fri., August 14, 1840, p. 2. www.newspapaers.com. Accessed 2/28/18.

- Rothman, Ellen K. Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1984.

- Theocritus, Junior [pseud.]. Dictionary of Love. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1858. www.archive.org. Accessed 2/5/18.

- “Tiffany and Co. History,” Tiffany & Co. www.press.tiffany.com. Accessed 3/2/18.

Romance and Sweet Dreams: Mid-19th Century Courtship

by Ann Haddad

.

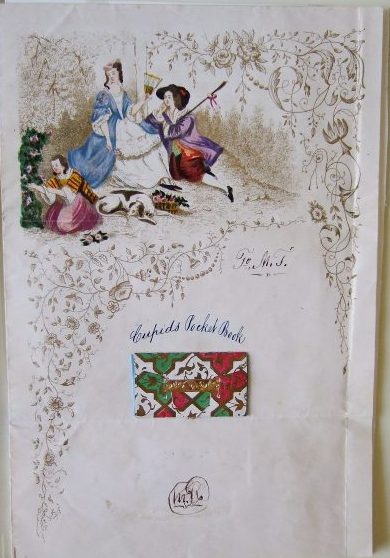

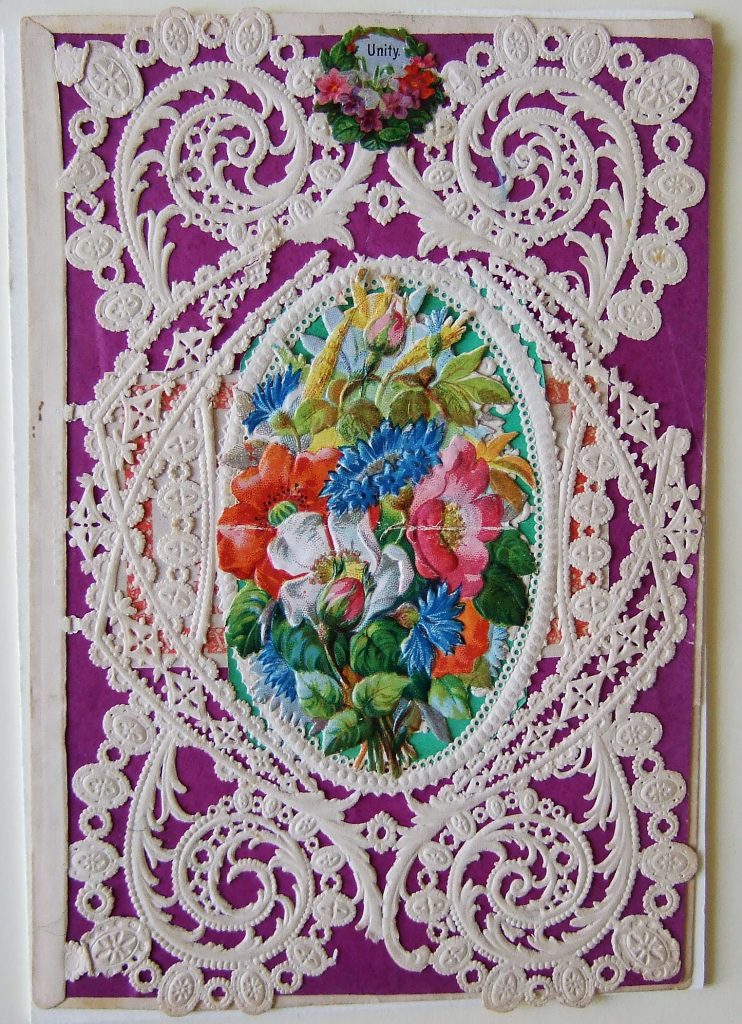

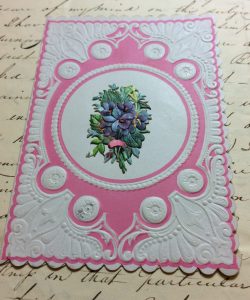

Valentines for an Eligible Lady

Valentine’s Day has been celebrated for centuries, but only became entrenched in American culture in the early 1840s, with the rise in popularity of commercially produced paper valentine cards. Made of delicately embossed and perforated lace papers, valentines became the fashionable way to convey romantic interest and to freely express the desire for romantic love.

The lovely Elizabeth Tredwell, eldest daughter of Seabury and Eliza, no doubt received her share of valentines from young men of her class. She was pretty and accomplished, and would certainly have been considered an eligible young lady. The Tredwell Archives contain several charming valentines; however, the senders and recipients are unknown.

On April 9, 1845, Elizabeth married Effingham Nichols (see our April 2017 blog post, “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing: The Marriage of Elizabeth Tredwell and Effingham Nichols”). We do not know when and how Elizabeth and Effingham met, nor are we aware of the length of their courtship. Based on the many strict codes of etiquette that governed courtship, however, we can assume theirs followed a dictated course.

.

.

.

Romantic Love

In the mid-19th century, romantic love was viewed as the solid rock upon which a healthy marriage was built; according to Karen Lystra, author of Searching the Heart (1989), it was only within the sacred state of marriage that one’s “ideal self” could be revealed. Courtship, therefore, was respected as a special time in the lives of a young couple. This period, after introductions and before a formal engagement, served to intensify the feelings of romantic love; to insure that the bond formed between a couple was true; to guide one in learning the real character of the other; and to ensure that their attraction was based on mutual respect and admiration. In Theocritus’ The Dictionary of Love (1858), it is defined as the period that is “all romance, excitement, hope, desire, expectation, and sweet dreams.”

Before Courtship: Under Mama’s Watchful Eyes

The time for a young woman to enter society and assume her role as a marriageable woman was determined by her parents; it depended not on her age, but on her level of maturity. A woman was also expected to have completed her education, or “finishing,” typically between the ages of 16 and 18, before entering society. Elizabeth most likely went “into company” (or “came out,” as it was later called) sometime around the age of 20.

Courting before this age was highly frowned upon. After completing her schooling, a daughter remained at home (which was viewed as a woman’s empire), under the watchful eyes of her mother. Here she learned domestic arts; assisted with rearing her younger siblings; and was instructed in the rules of manners and civility, which were highly valued in society. A young lady was chaperoned at public entertainments, such as theatre or dances, by her parents, brothers, or an intimate family friend. (Once she became formally engaged, her lover became her “legitimate protector and companion.”) She was expected to rebuff any male attention, and maintain a polite disinterest in courtship. Mrs. John Farrar, in A Young Lady’s Friend (1837), writes,

“The less your mind dwells upon lovers and matrimony, the more agreeable and profitable will be your intercourse with gentlemen. Regard men as intellectual beings who have access to certain sources of knowledge to which you are denied.”

Elizabeth also received guidance from her mother (likely culled from popular advice books such as Lydia Maria Child’s The Frugal Housewife (1829); Godey’s Lady’s Book; and etiquette and conduct manuals) about acceptable behaviors that reflect what Mrs. John Farrar called “delicacy and refinement” when in the company of young men. Never let a man hold your hand; decline his offer of assistance with getting in and out of carriages; never squeeze into a tight space with a gentleman; never speak of your private affairs or feelings; always have a friend present for carriage rides; never borrow money from a man; avoid gossip. Mrs. Farrer stressed:

“Your whole deportment should give the idea that your person, your voice, and your mind are entirely under your own control. Self-possession is the first requisite to good manners.”

Above all, a young lady was never to make obvious public plays for the attention of a young man, or insinuate that she wanted an invitation from him. According to T.S. Arthur, author of Advice to Young Ladies (1847), such inappropriateness indicated “an outrageous want of all decent respect for herself.”

Money and Religion