“A Scene of Radiant Joy:” The Wedding of Elizabeth Tredwell & Effingham Nichols

by Ann Haddad

This is the fourth and final of a series of blog posts on mid-19th century courtship and wedding customs. Click for Part One, on 19th century courtship; Part Two, on marriage proposals and engagements; and Part Three, on wedding preparations.

A “Royal” Wedding in Old New York City

The recent marriage of Prince Harry, the younger grandson of Queen Elizabeth, and Meghan Markle, an American actress, caused a stir both in England and in America. Even those who scoff at the notion of monarchy may have been entranced by the pomp and spectacle surrounding the “Royal Wedding,” finding it to be both thrilling and heartwarming.

In 19th century New York City, there was a flourishing royalty of a sort, led by the “merchant princes,” whose success in business and resulting wealth endowed them with economic and social power. Seabury Tredwell was one such wealthy merchant, and the marriage of his eldest daughter, Elizabeth, to Effingham Nichols, on April 9, 1845, could also be considered a ‘“royal” event, for it united two established families who occupied prominent positions among the aristocratic elite of New York society.

Why April?

Why did Elizabeth choose an April wedding, and on a Wednesday? Spring was always a popular time for nuptials; perhaps Effingham’s work as an attorney eased up a bit in April. Or perhaps Elizabeth was familiar with the old adage:

“Marry in April when you can,

Joy for Maiden and for Man.”

Tuesdays, Wednesdays or Thursdays were usually chosen for a wedding, likely because the clergyman was frequently occupied with his regular pastoral duties on the weekend.

Church or Parlor?

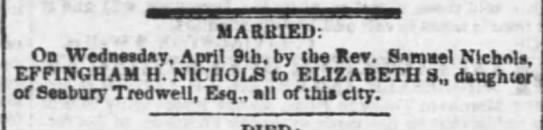

In 1845, American wedding practices were on the cusp of great change. Weddings were evolving from simple, intimate family affairs to elaborate public events, rich in tradition and ritual. We have no surviving records that describe the Tredwell and Nichols union. The only certainty is the date of their wedding and the officiant, the Reverend Samuel Nichols, father of the groom. (Coincidentally, the Reverend James Milnor, who officiated at Seabury and Eliza’s wedding on June 13, 1820, at St. George’s Chapel, died on April 8, 1845, the day before Elizabeth’s wedding.)

Elizabeth and Effingham’s marriage announcement, published on Friday, April 11, in the New York Evening Post, did not mention a church wedding, so chances are that the couple were wed in the elaborate Greek Revival double parlor of the Tredwell home on Fourth Street.

.

.

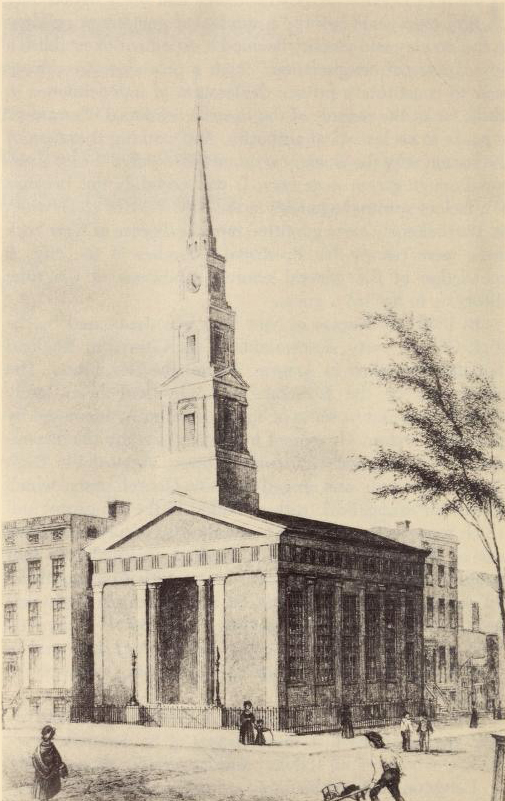

If the couple had been married in church, it most likely took place at St. Bartholomew’s, then located at Great Jones Street and Lafayette Place, one block away from the Tredwells’ home. In the mid-19th century, there was a growing trend away from small weddings held in the bride’s family parlor, in favor of a church wedding. A church’s large public space accommodated more guests. If Elizabeth and Effingham had been married at St. Bartholomew’s instead of at home, the Tredwells might have chosen a church setting for this reason; or because of the close ties both families had with St. Bartholomew’s. Effingham Howard Warner, the groom’s uncle and namesake, was one of its founders, and the Tredwells had worshiped there since its consecration in October 1836, one year after their move to the elite Bond Street neighborhood.

Your Hosts: Mr. and Mrs. Tredwell

Whatever location was chosen for the wedding ceremony, there was never any choice as to the venue for the reception: custom dictated that it be hosted and paid for by the bride and her parents at their home. As Elizabeth was the first of their children to marry, Seabury and Eliza likely seized the opportunity to display their wealth, refinement, and sophistication, both for their children’s benefit (five unmarried daughters were still at home), and to impress their guests.

Set and Lighting Design for the Performance

In preparation for Elizabeth’s marriage, the entire Tredwell house must have been turned upside down, for although the grand double parlor was the main stage for the action, the entire house required cleaning from top to bottom; everyone, especially the Tredwells’ four servants, was engaged in this task. New furnishings may have been purchased; and, to show the home to its best advantage, additional lighting may have been rented for the occasion. The house was elaborately decorated with an abundance of white flowers that covered nearly every surface, possibly ordered from Dunlap & Carman, located at 635 Broadway, near Bleecker Street. Musical entertainment, ranging from a soloist at the pianoforte to a quartet, may have been arranged; and dancing was common at evening wedding receptions.

In a diary entry from Wednesday, February 19, 1845, Mrs. Abiel Abbot Low described the process of readying a house for a wedding reception:

“Mr. Nevers made preparations for lighting the house. This afternoon he is having a chandelier with four burners in each parlor, four solar lamps at the folding doors, and two candelabras for five candles each, on either side of the mirrors. Abbot bought a handsome brussels carpet for the tearoom, and a handsome sideboard, as a pleasant surprise for me. Borrowed a few pieces from our friends, including a full length mirror for the ladies’ dressing room.”

Mary Harris Lester summed up the whirlwind of activity surrounding the house preparations when she hurriedly wrote in her diary on Monday, December 15, 1847, just several days before her wedding:

“Mother went with me today to order things for next Monday evening, have a great deal to attend to at present.”

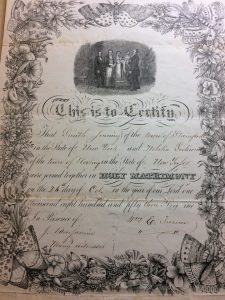

License Not Required

In 1845, the only available record that provided proof of marriage was the bridal certificate, issued by the church where the wedding was held, or, in the case of home weddings, obtained by the clergyman from his own parish church. Prior to 1847, no marriages were recorded by any cities or towns in New York State. Wedding announcements were traditionally published in local newspapers within several days of the event.

Dressing the Bride

The Art of Good Behavior (1845) states unequivocally that “it is the duty of the bridesmaids to assist in dressing the bride.” On Elizabeth’s wedding day, she was almost certainly assisted by her sisters Mary (then age 20) and Phebe (age 16). They most likely dressed in one of the bedrooms on the third floor. After dressing themselves in their own simple white dresses, the sisters helped Elizabeth into her wedding dress; tied up her silk or satin slippers; affixed her lace or net veil with a wreath of orange blossoms, as was the fashion (being careful not to disturb Elizabeth’s hair, which had been dressed at home by a hairdresser); put on her gloves; and, when all else was in readiness, hand her a white leather prayer book or embroidered handkerchief to carry.

Toasting the Groom

The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852) states the essential requirements of the groomsmen: “Young and unmarried they must be, handsome they should be, good humored they cannot fail to be, and well dressed they ought to be.”

It was customary for the groom, after dressing at home, to meet his groomsmen at the home of his future wife. Upon arriving at another third floor bedroom in the Tredwell house, Effingham may have found his friends gathered around a punch bowl, ready to toast him with a tumbler or two, and to make sure that he, too, enjoyed a nip of “liquid courage.”

The chief groomsman also needed to be certain that the wedding ring, wrapped in silver paper, was securely placed into the groom’s waistcoat prior to the ceremony. Among his other duties was to greet the clergyman upon his arrival and introduce him to the family and friends who gathered in the parlor to witness the ceremony. It is at this time that he obtained the certificate of marriage from the clergyman, to present to the groom after the reception.

Here Come the Bride and Groom!

Once a servant announced to the gentlemen that the ladies were ready, the men joined their partners in the hallway, and, arm in arm, with the bridal pair bringing up the rear, descended the staircase to the parlors on the first floor, where the invited guests were waiting. Even if Elizabeth had been married in church, her father, Seabury, most likely did not escort her; contemporary diaries of this period indicate that the bride and groom simply took their place before the altar. It wasn’t until the mid-late 19th century and the prevalence of church weddings that the ritual of the father “giving away his daughter” became commonplace.

Upon entering the front parlor, the bridal party positioned themselves in a semicircle facing the guests, who were either seated or standing, depending on the number attending. The bride stood to the right of the groom, and was flanked on her right by her bridesmaids; the groomsmen stood to the left of the groom. The clergyman then proceeded with the ceremony, taken from The Book of Common Prayer; vows were exchanged; then the groom removed from his waistcoat pocket the plain gold wedding ring (perhaps engraved with their initials and the wedding date) and placed it on the fourth finger of the bride’s left hand.

Mrs. Nichols

Once the nuptials were completed and Effingham kissed his bride, the clergyman addressed Elizabeth for the first time by her newly acquired name, “Mrs. Nichols.” The newlyweds were congratulated first by Seabury and Eliza, then Effingham’s parents, followed by family and friends, who were escorted to the couple by the chief groomsman.

After all the congratulations had been offered, the bridal party was free to mingle with the guests.

At some point after the ceremony, it was the responsibility of the chief groomsman to quietly thank and compensate the clergyman for his services. The sum was determined by the financial ability and generosity of the groom.

Henry Patterson wrote in his diary of his wedding, which took place on Thursday, July 18, 1844:

“Thursday [the wedding day] I spent at my usual business until four o’clock, [note that he worked as usual on his wedding day!] then went home and dressed. ….went to Mrs. Wright’s at 7 o’clock. From then until a quarter after eight the company was assembling and preparations going forward then all being ready, Ophelia acting as bridesmaid and Turner as groomsman, we walked into the room, and were immediately married by Mr. Hatfield. The ceremony was short, but impressive, and suited us both. After receiving the congratulations of our friends who were present, the evening was passed with conversation, a little music, and by eleven o’clock all had dispersed.”

And on December 27, 1855, Edward Tailer wrote sweetly in his diary of his wedding to Agnes Suffern, and of the moment when he first heard his wife addressed by her married name:

“The Dr. read the service in an impressive manner and occasionally a tear could be seen trickling down the face of those who loved us both, and who had our interests at heart, but a few moments sufficed to proclaim us to be man and wife, and it was not until I heard our mutual friends calling Agnes “Mrs. Tailer,” that I could realize that any change had taken place or that new responsibilities have been assumed by me. It was a pleasant affair, and all appeared to enjoy themselves, about 110 persons being present. Numerous were the congratulations of our friends and if all the kind wishes which were expressed within my hearing could only be realized, I shall be a very happy man.”

Eat, Drink, and Faint!

Guests to a home wedding were usually invited for 8 p.m. Other than the requirement that the wedding reception be held at the bride’s parent’s home, there were no hard and fast rules about the number of guests, the type of reception, or the entertainment. Upon arriving at the Tredwell home, guests proceeded directly up to the second floor, where Seabury and Eliza’s bedroom had been turned into “dressing rooms,” for guests to fix their hair, adjust their gowns, or polish their boots, assisted by one or two servants. They then went down to the front parlor, where Mr. and Mrs. Tredwell greeted them as for any sociable.

Depending on the size of the guest list, Mrs. Tredwell may have elected to have the wedding buffet feast catered, perhaps by William A. Tyson (see advertisement of December 24, 1846), who, in addition to preparing the food, provided equipment, servers and cooks to assist with the reception. The lavish “wedding supper,” which was typically served at 11 p.m., consisted of oysters, cold meats, fish, fruits, and various confections. Beverages included lemonade, punch, wine, and champagne. The table was usually set up in the rear parlor and the overflow of the many guests spilled into the halls and tea room. Imagine the scene of the Tredwell front hall, tearoom, and both parlors crowded with guests trying to reach the supper table!

Mrs. Abiel Abbot Low wrote in her diary Sunday, February 2, 1845, of one parlor wedding she attended:

“I should judge there were more than three hundred present during the evening. I never was at so crowded company before. There was a band of music and some dancing during the evening. Supper was announced at 11 o’clock and a most bountiful and elegant repast it was, but such crowding in a supper room I never witnessed before. The drawing room was so warm at one time, and the air so perfumed with the profusion of flowers that several of the ladies fainted. We returned home between 12 and 1 o’clock.”

John Hadden, a young man who lived at 20 Lafayette Place, right around the corner from the Tredwells, could have been describing the Tredwell home when he wrote of a lively and somewhat chaotic wedding reception he attended on Tuesday, January 17, 1843:

“It was a very pleasant party. The whole house was open. The two drawing rooms for dancing, and on the back stoop which was enclosed a small room [like the Tredwell tea room] with a little refreshment, punch and lemonade with cake, the piazza having a couch where the bride sat and received the company. The second story back room for the ladies, the front room for the gents. As usual at most crowded parties the company went to the supper room about 3/4 of an hour before things were ready and we had to stand until everything was in order. Before this was accomplished Mr. Wright took up a bottle of champagne from the table and was about to open it, one of the waiters told him the table was not ready yet, but he took it out of the supper room with him and opened it somewhere else.”

For those of lesser financial means, a simple menu of wedding cake, wine, and lemonade was customary. Usually within two hours after the reception commenced, the bride quietly left the festivities and, escorted by her attendants, retired to her bedroom. There they helped her undress and perform her “night toilette.” According to The Art of Good Behavior (1845): “The groom retires without ceremony or notice.” According to contemporary diaries, guests typically lingered until anywhere between 11 p.m. and 2 a.m.

Let Them Eat Cake

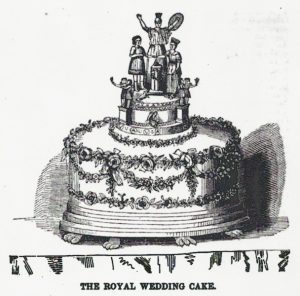

Until the mid-1850s, when tiered cakes became popular, the bridal cake was usually of a single layer, and typically consisted of a rich, dark fruitcake covered in almond paste and a hard, white sugar icing. It was either baked at home or, as was probably the case with Elizabeth’s cake, ordered from one of the many confectioners in the city that prepared fancy desserts, such as James Tompson’s Premium Bakery, located at 40 Lispenard Street.

The cake, usually decorated simply with fresh flowers, was placed on a rectangular table covered with a white cloth. When the cake was ready to be cut, Elizabeth and Effingham sat in front of it, surrounded by their bridesmaids and groomsmen, who stood at either side, while their parents took their places at either end. The rector stood opposite the bride and groom. Champagne was usually served, then the chief groomsman offered a toast to the newly married couple, and to the health of the parents of the bride. The bride then cut the cake (sometimes with a special saw, as the cake was typically too thick and hard to cut with a regular knife!), which her bridesmaids, assisted by the servants, distributed to the guests.

Wedding Favors for Dreaming

It was customary for the bride and groom to give away tiny boxes of wedding cake to guests. These slices were cut from a second cake baked specifically for this purpose before the wedding. Many stationers, such as Stouts, located at the corner of Broadway and Maiden Lane, advertised special cake boxes, as in this ad from December 21, 1848: “elegant boxes for cake at $8 per hundred.” Mary Harris Lester wrote on the eve of her wedding on December 18, 1847, “… house all in order quite busy all evening in tying up boxes of cake.”

The evening before the wedding, the bridesmaids helped the future bride to ready the cake boxes, which were distributed to the guests upon their departure from the reception.

It was important for newlyweds to let their friends and acquaintances know when they would commence receiving well-wishers at their home upon returning from their bridal tour. A new “at home” card was made expressly for this purpose; it was attached to the wedding cake boxes as a convenience for the guests. Stout’s wedding cards were advertised as “elegantly engraved and printed…”

Etiquette and fashion experts stressed that a woman may not distribute a card bearing her married name until after she utters her marital vows. As stated in the New York Evening Mirror on November 14, 1844: “It is tampering with serious things, very dangerously, to circulate the three words ‘Mrs. John Smith,’one minute before the putting on of the irrevocable ring. The first proper use of the wedded name is to send it with parcels of wedding cake … to friends and persons desired as visiting acquaintances.”

Elizabeth and Effingham’s “at home” card may have been written as:

Mr. and Mrs. Effingham Nichols

at home

on the morning of Tuesday, Wednesday,

Thursday, and Friday next,

from 12 till 4.

361 Fourth St.

A popular tradition surrounding the boxed wedding cake called for an unmarried lady to sleep with the cake beneath her pillow on the night of the wedding. As a result her dreams would be “sweetened,” and she would be granted a vision of her future husband.

Wedding Gifts

At the time of Elizabeth and Effingham’s marriage, wedding gifts were usually bestowed only by the immediate family and very close friends of the couple. They were never of a practical nature (giving such gifts would be perceived as an insult, for it would imply need on the part of the receiver); in fact, they usually denoted a personal relationship with the bride and were often handmade. Typical gifts included shawls, clocks, fancy fans, richly ornamented thimbles, pictures, gold pencils, and gift books. Two popular books were The Bridal Keepsake, by Mrs. Coleman (1846), a collection of writings on religious and moral themes, and Austin’s Voice to the Married (1848), advertised as “The Best Bridal Gift.”

As the century progressed, it became more common to receive wedding gifts from relatives and friends. By the late-19th century, gift-giving became so profuse (a custom frequently renounced by preachers, etiquette manuals, and Godey’s Lady’s Book) that among the elite, special areas of the future bride’s home were set up to display the items; the bride-to-be would offer visiting hours to show off her silver and other acquisitions, which silently announced that her future prosperity was assured.

Silverware was always a gift to the bride, and thus was always engraved with the bride’s maiden name or initials; Elizabeth’s silver thus bears the mark “E.T.”

The “Bridal Cushion”

One popular wedding gift offered for sale by fancy dry-goods stores in the 1840s was the “bridal cushion.” Known as a Globe de Mariee in France, where the custom originated, it consisted of a tufted velvet cushion, usually red in color, that sat under a glass dome or globe decorated with gilt metal flora and fauna, as well as little mirrors. It was used to convey the love and hope brought to a marriage through meaningful objects accumulated by the couple throughout their lives. The bride would nestle her wedding mementos on the cushion; over the years she would add significant objects to the display. The cushion occupied pride of place in the Victorian parlor. Guests shopping for a bridal cushion for Elizabeth may have patronized Woodworth’s, located at 325 Broadway. In an advertisement on November 2, 1841, the shop offered “a new and beautiful collection of French Fancy Articles…which have been selected with great care by our tasteful agents in Paris.”

The Bridal Tour

The post-wedding trip, or bridal tour, taken by couples was an imitation of a ritual begun in 19th century England. Typically lasting one to two weeks, the journey served to as a means by which the pair traveled to visit friends and family who could not attend the wedding ceremony. Fashionable spots included Philadelphia, Washington D.C., as well as Niagara Falls and other natural wonders that were not too far from home. Overseas trips were largely unheard of. Couples were often accompanied by relatives or close friends. In the late 19th century the bridal tour became an exclusive, private trip for the newlyweds, and evolved into what we know of today as the traditional honeymoon.

Make Room for the Groom

As Charles Bristed mentioned in The Upper Ten Thousand: Sketches of American Society (1852): “It is the invariable custom that the young couple shall reside with the bride’s father for the first four or six months.”

Judging by the contemporary diaries of the period, very little advance preparation or thought was given to the groom’s move into his wife’s family home. In fact, like so many of the other wedding customs at this time, it was all rather last minute. On December 26, 1855, the day before his wedding, Edward Tailer wrote in his diary: “Mother assisted me in packing my trunk, and I am to send it over to Mr. Suffern’s [his father-in-law] after dark.”

And Henry Patterson wrote in his diary on July 21, 1844: “Wednesday forenoon [the day before the wedding] I sent my furniture, clothing, etc. to Mrs. Wright’s.

Bristed provided a hilarious description of the items his fictional groom brought to his bride’s home (earlier on the day of his wedding!):

“… seven coats and twelve pairs of trousers, and about thirty waistcoats, no end of linen, and carpet-bags full of boots, a gorgeous dressing-gown, and Turkish slippers, and smoking cap, and cigars numerous, and all sorts of paraphernalia generally, until the little dressing room adjoining the nuptial chamber is overflowing with foppery.”

Gaining A Son

After returning from their bridal tour, Effingham and Elizabeth took up residence in the Tredwell home on Fourth Street, and, in a decided departure from tradition, remained there for eleven years! (For a description of their married life, see the blog post of April 2017 “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing). Once settled at home, they commenced receiving congratulatory wedding calls from friends and acquaintances. In keeping with the custom of the time, Elizabeth may have worn her wedding dress, without the veil, for these visits.

Love’s Devotion

As Elizabeth and Effingham enter into the “divine” institution of marriage, let us imagine a lovely scene similar to the one described in the following poem, “Eras of Life: Marriage,” by Mrs. A.F. Law, which appeared in the January 1851 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book:

“One sacred oath hath tied

Our loves; one destiny our life shall guide;

Nor wild nor deep our common way divide!

Ushered thus, we haste to enter on a scene of radiant joy—

List’ning vows in ardor plighted, which alone can death destroy.

Passing fair the bride appeareth, in her robes of snowy white,

While the veil around her streameth, like a silvery halo’s light;

And amid her hair’s rich braidings rests the pearly orange bough,

With its fragrant blossoms pressing on her pure, unclouded brow.

Love’s devotion yields the future with young Hope’s resplendent beam;

And her spirit thrills with rapture, yielding to its blissful dream!”

Sources:

- Abell, L.G. Woman in Her Various Relations: Containing Practical Rules for American Families. New York: J.M. Fairchild & Co., 1855.

- Allen, Emily. “Culinary Exhibition: Victorian Wedding Cakes and Royal Spectacle.” Victorian Studies Vol. 45, No. 3 (Spring 2003), pp. 457-484. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3830185.

- Anonymous. The Art of Good Behavior, and Letter Writer, on Love, Courtship, and Marriage: A Complete Guide. New York: Huestis & Cozans, 1845. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society.

- Anonymous. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony. London: David Bogue, 1852. books.google.com. Accessed 1/18/18.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Tuesday, November 2, 1841, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 3/16/18.

- Bristed, Charles Astor. The Upper Ten Thousand; Sketches of American Society. London: John W. Parker and Son, 1852. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 2/13/18.

- The Evening Post. Friday, April 11, 1845, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/9/18.

- The Evening Post. Thursday, December 21, 1848, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 2/19/18.

- Godey’s Lady’s Book. Volume 42: January, 1851. www.hathitrust.org. Accessed 3/18/18.

- Hadden, John. Diary, 1841-1843. Rare Books and Manuscripts Division, New York Public Library.

- Lester, Mary H. Diary, 1847-1849. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Low, Harriet. Diary, 1844-45, Low Family Papers, 1750-1900. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- New York Daily Herald. Tuesday, March 26, 1844, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/6/18.

- New York Evening Mirror in the Buffalo Daily Gazette. Thursday, November 14, 1844, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 2/19/18.

- New York Tribune. Thursday, December 24, 1846, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/4/18.

- O’Neil, Patrick W. Tying the Knots: The Nationalization of Wedding Rituals in Antebellum America. Dissertation Thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2009. www.cdr.lib.unc.edu. Accessed 3/15/18.

- Patterson, Henry. Diaries, 1832-1848. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Rothman, Ellen K. Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Tailer, Edward Neufville. Diaries, 1848-1917. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Thornwell, Emily. The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility: In Manners, Dress, and Conversation. New York: Derby & Jackson, 1856. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/17/18.

- Wallace, Carol McD. All Dressed in White: The Irresistible Rise of The American Wedding. New York: Penguin Books, 2004.

- Young, Leonard. A Short History of St. Bartholomew’s Church in the City of New York, 1835-1860. www.archive.org. Accessed 4/2/18.

This series on 19th century courtship and the wedding has been absolutely wonderful. In fact all of the posts are so informative, so well researched, They provide a much needed collection of specific facts about the family and in the case of a dearth of recorded facts, intelligent and probable conjecture. This particular post is so valuable. Interesting how some customs persisted while others dropped out. (The last thing I would have wanted would be to have my new husband move in with me and my parents!!! Can you imagine?? Says something I think about the trepidation some women had in leaving their childhood home. Today, most of us can’t wait to get out on our own. As for the bridal cushion, I never heard of this. Probably good riddance.

You are so right, Mary, with regards to the bride’s reluctance. I read a number of diary entries that refer to her weeping, and her somber mood during the ceremony. But family and friends enjoyed the festivities afterwards, and hopefully, so did the bride.

Always love and appreciate your comment, Mary. Thank you!