Uncle Sam(uel): Bishop, Loyalist … Broadway Star?

by Ann Haddad

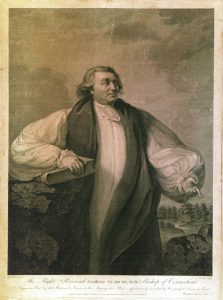

Samuel Seabury |

Early in Act I of Hamilton, as I sat entranced by Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway mega-hit, a rapper in clerical garb mounted a box, and, in a song entitled “Farmer Refuted,” cried out, “Here ye, hear ye! My name is Samuel Seabury and I present…”

I was immediately taken aback. “Samuel Seabury? Seabury Tredwell’s namesake and uncle? Is this the same guy whose portrait adorns one wall in the Tredwell family room? What is he doing here, in a hip-hop musical about Alexander Hamilton?”

Reverend Samuel Seabury (1729-1796), was the half-brother of Seabury Tredwell’s mother, Elizabeth Seabury. Born in Groton, Connecticut, Seabury completed his education at Yale in 1748, and in 1752 earned a degree in medicine at the University of Edinburgh.

One year later, like his father before him, he was ordained into the Episcopal Church in London, and returned to America, where he served as Anglican rector in various parishes in New Jersey, in Queens County, and, during the American Revolution, in St. Peter’s Church in Westchester, New York.

The Pamphlet Wars: Seabury vs. Hamilton

.

.

.

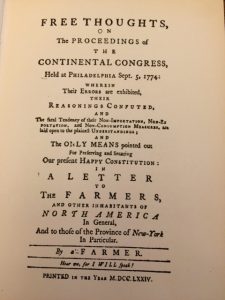

Like most other High Church Anglicans, who were considered officials of the Church of England, Seabury was a staunch Loyalist during the American Revolution. In 1774, as Westchester farmers grew uneasy over the effects of the Continental Congress’ newly imposed trade embargo against Great Britain, the 45-year-old cleric launched a series of pamphlets in the New-York Gazetteer.

Using the pseudonym “A. W. Farmer” (A Westchester Farmer), in “Free Thoughts on the Proceedings of the Continental Congress,” and “The Congress Canvassed,” Seabury vehemently attacked the patriots, calling them “scorpions,” and warned the colonists that they would suffer economic ruin as a result of the embargo:

“Should the government interpose, we shall have no trade at all, and consequently no venue for the produce of our farms.”

.

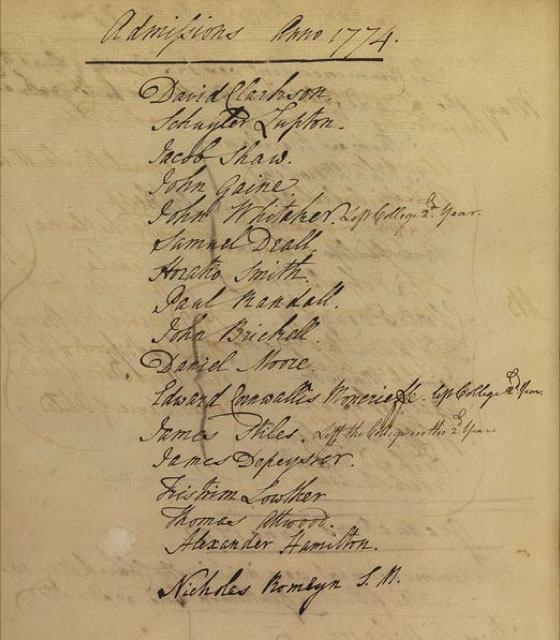

Kings College Admission List, 1774 Columbia University Archives |

The outcry from the patriots was swift. One who voiced his opposition in print was an ambitious 19-year-old student at King’s College (now Columbia University) named Alexander Hamilton. In an anonymously published pamphlet entitled “A Full Vindication of the Measures of the Congress,” Hamilton expressed support for the rebels who had carried out the Boston Tea Party, and defended the trade embargo:

“It was hardly to be expected that any man could be so presumptuous, as openly to controvert the equity, wisdom, and authority of the measures, adopted by the congress: an assembly truly respectable on every account!”

Samuel Seabury spiritedly rebutted Hamilton’s pamphlet with two more of his own, “To the Merchants of New York,” and “A View of the Controversy Between Great Britain and her Colonies,” in which he “sees the influence of Congress daily diminishing,” and mocked Hamilton’s words:

“You had no remedy but artifice, sophistry, misrepresentation and abuse: these are your weapons, and these you wield like an old, experienced practitioner.”

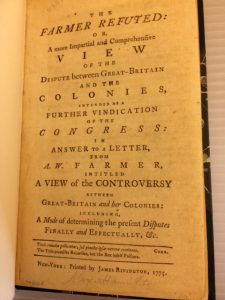

In a glowing display of writerly prowess, Hamilton followed with another rebuke, entitled “The Farmer Refuted,” published in February of 1775:

In a glowing display of writerly prowess, Hamilton followed with another rebuke, entitled “The Farmer Refuted,” published in February of 1775:

“Candour obliges me to acknowledge that you possess every accomplishment of a polemical writer which may serve to dazzle and mislead superficial and vulgar minds; a peremptory dictatorial air, a pert vivacity of expression, an inordinate passion for conceit, and a noble disdain of being fettered by the laws of truth.”

Hamilton concludes his tour-de-force with: “I verily believe also, that the best way to secure a permanent and happy Union, between Great-Britain and the colonies, is to permit the latter to be as free, as they desire.”

This early defense of the patriots’ cause would serve to establish Hamilton as an important political figure. The battle of ideas between Seabury and Hamilton would later come to be known as the “Pamphlet Wars.”

Loyalist Prisoner, Physician, and Chaplain

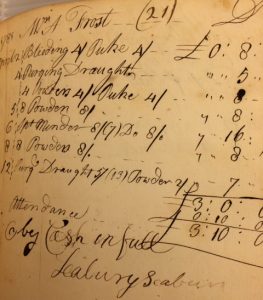

Ledger Page from Samuel Seabury’s Account Book, 1780-1781. NYHS Manuscript Collection |

After he signed the White Plains Protest of April, 1775, a proclamation of allegiance to King George III, Seabury was taken prisoner by a patriot militia; his family was terrorized; and he endured the humiliation of being paraded through the streets of New Haven as a prize captive. Eventually, Seabury was released, and returned to New York City, where he was protected by the British occupation and allowed to practice medicine. His ledger book from 1780-1781 indicates that he relied on the few commonly prescribed medical treatments, such as purging, bleeding, and blistering. His journal includes notes made while treating sailors on the Munificence, a British prison ship. For his loyalty to Great Britain during the war, Seabury was made chaplain to the King’s American Regiment.

First Episcopal Bishop of America

While most Loyalists fled to Canada after the war, Samuel Seabury returned to Connecticut, and resumed his duties as rector. His life on the public stage, however, was far from over. In November of 1784, he was consecrated as the first American Episcopal Bishop, after the Church severed its political ties with the Church of England. For the rest of his life, Seabury made inroads towards reforming the liturgy and organization of the Episcopal Church in America. Although criticized for his opposition to increasing the role of the laity in the church, he was greatly admired as a spiritual leader, and he strongly contributed to the spread of the Episcopal Church in New England. He died in New London, Connecticut, in 1796, at the age of 66. At the time of his death, his 16-year-old nephew, Seabury Tredwell, was two years away from his move to New York City. No doubt the Tredwells’ connection to such a prestigious clergyman was not lost on their fellow Episcopalians; most likely it enhanced their stature and prominence in the New York community.

The Tredwells’ ground floor family room. Notice the engraving of Samuel Seabury between the windows.

It is ironic that Samuel Seabury, a die-hard Loyalist during the American Revolution, would play so significant a role in the rise to power of one of the Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton. On this July 4th, as we celebrate our rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, it is fitting to acknowledge the efforts of a man who, although a Loyalist, wasn’t afraid to declare his “free thoughts.” Do you think the Tredwell family would react with amusement or with horror to the sight of Uncle Samuel Seabury once again taking the stage in New York?

Sources:

- Images of Free Thoughts on the Proceedings of the Continental Congress, 1774 and The Farmer Refuted, 1775 courtesy New York Historical Society.

- Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin Press, 2004.

- [Hamilton, Alexander]. A Farmer Refuted. New York: James Rivington, 1775.

- [Hamilton, Alexander]. A Full Vindication of the Measures of the Congress. New York: James Rivington, 1774.

- Farmer, A.W. [Seabury, Samuel]. Free Thoughts on the Proceedings of the Continental Congress. New York: James Rivington, 1774.

- Farmer, A.W. [Seabury, Samuel]. A View of the Controversy Between Great Britain and Her Colonies. New York: James Rivington, 1774.

- Lynch, Wayne. “Reverend Seabury’s Pamphlet War.” Journal of the American Revolution, July 9th, 2013. https://allthingsliberty.com 5/1/16.

- Miranda, Lin-Manuel and Jeremy McCarter. Hamilton The Revolution. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2016, p. 49.

- Seabury, Samuel. Account Book, 1780-1781. New York Historical Society Manuscript Collection.

- Seabury, Samuel. Memorial Setting Forth His Services and Circumstances, 20 October 1783, reprinted in Seabury, William Jones. Memoir of Bishop Seabury. Rivington’s, London, 1908, p. 142.

- Thoms, Herbert, M.D. Samuel Seabury. Hamden, CT: The Shoestring Press, 1963.

- Vance, Clarence H., Ed. Letters of a Westchester Farmer by the Reverend Samuel Seabury. White Plains, N.Y.: Westchester County Historical Society, 1930.

I vote for horrified—can’t imagine what they would think of a rapper in clerical garb—let alone a rapper portraying Uncle Seabury!

Very interesting background on the Tredwell family!

Great article. This is the second person from history I’ve “met” because of Hamilton lyrics.

At first I thought the Tredwell family might be horrified to see him portrayed as a Rapper.

However, on second thought most probably they would say isn’t just like Uncle Seabury. He always was one to buck tradition and was never afraid to take on controversial issues.

I had know about Seabury’s connection to the founding of the American Episcopal church, but not of his connection to Hamilton. This contest between the two men is just one more example of how modern political wrangling is nothing to that of the Revolutionary & Federal periods. Thank you for bringing this history to light & increasing our appreciation for the Merchant’s House in the process.

What a wonderful post! It’s exciting to add this background to our understanding of the Tredwell’s. I so look forward to reading your posts!

Your interesting article makes me realize that while one can try to understand the past, there really is no way to guess what is coming in the future. I’m glad Samuel Seabury did not win the political argument, but of all the dire thoughts he may have had about the future of the colonies, I am sure being presented in clerical garb doing rap on Broadway wasn’t one of them.

[…] Samuel Seabury was the grandson of Seabury Tredwell’s uncle, also named Samuel Seabury. See Uncle Sam(uel): Bishop, Loyalist … Broadway Star? for more information on the original Rev. […]