“A Meritorious Establishment:” Tredwell Philanthropy, Part 3

by Ann Haddad

An Elite Education for the Tredwell Children

Like other affluent New Yorkers, Seabury and Eliza Tredwell chose to send their children to private day and boarding schools. Although little is known about their elder son Horace’s education, we do know that Samuel Lenox was sent to the prestigious St. Paul’s College in College Point, New York (see my blog post of September 2016). The six Tredwell daughters attended private neighborhood schools, including Mrs. Okill’s Academy on nearby Clinton Street (now 8th Street), and Miss Gibson’s School on Union Square.

The Calamity of Ignorance

Most New York City children who were fortunate enough to receive an education, however, did so at one of the many church-based charity schools, or by the nondenominational New York Free School Society (FSS), which was founded in 1805 to provide a free education to the city’s poor children whose families were not connected with any religious organization. DeWitt Clinton, then Mayor of New York City, who spearheaded the Free School Movement, said of the importance of educating the poor:

“The necessity was so pressing, the calamity of ignorance so appalling, that the problem of removing the crying shame could not be set aside or postponed.”

By 1825, aided by public funding, the FSS had educated nearly 20,000 children.

Falling Through the Cracks

Despite these successful efforts by the churches and by private philanthropy to provide children with free education, roughly 43,000 other youth, largely from indigent households, fell through the cracks. Neglected and living in poverty, they did not attend school; instead, these “loafers” and “ragamuffins” roamed the streets, often taking up lives of petty theft and vagrancy. If arrested and imprisoned, even for minor infractions, these young offenders were indiscriminately incarcerated with adults in overcrowded and rundown prisons; this disastrous combination resulted in many juveniles returning to society as hardened criminals. The conditions of the City Prison, commonly known as Bridewell, was described as follows:

“In rooms about 18 feet square, there are often thirty or forty persons, confined together, without any discrimination except that of sex and color – boys of nine years of age and upwards, sharing the same dismal fare, and mingling in conversation with aged villainy, – and girls of ten or twelve exposed to the company and example of of the most abandoned of the sex.”

The House of Refuge

In 1824, a group of wealthy and philanthropic New Yorkers, including Cadwallader D. Colden (1769-1834), a former Mayor of New York City, recognized the need to establish a facility where young petty offenders could be segregated from adults criminals, to avoid “the contamination of youth by vicious associations.” On January 1, 1825, after raising $20,000 through private donations, the House of Refuge for Juvenile Delinquents opened its doors on Broadway (then Bloomingdale Road) and 23rd Street, in a former Federal arsenal. The first institution of its kind in America, the House of Refuge sought to rescue poor and destitute children from lives of delinquency. The outgrowth of the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism, the House of Refuge was privately managed, but supported in part by New York State and City funds.

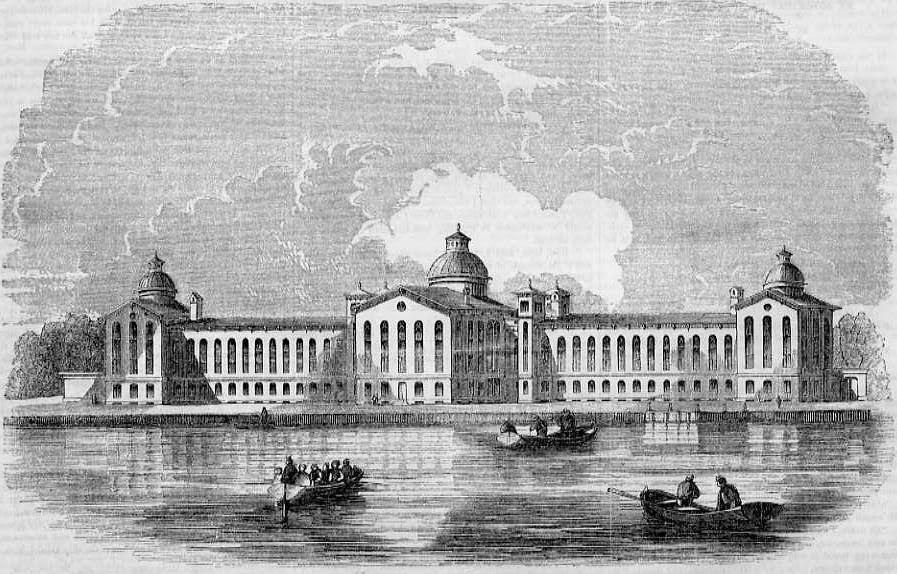

Under the supervision of Joseph Curtis, the institution opened with an enrollment of three boys and six girls. By 1832, it had outgrown its accommodations and moved to 23rd Street and the East River. It’s next and final move occurred in 1854, when it relocated to a facility on Randall’s Island that could accommodate 1,200 children.

Habits of Industry

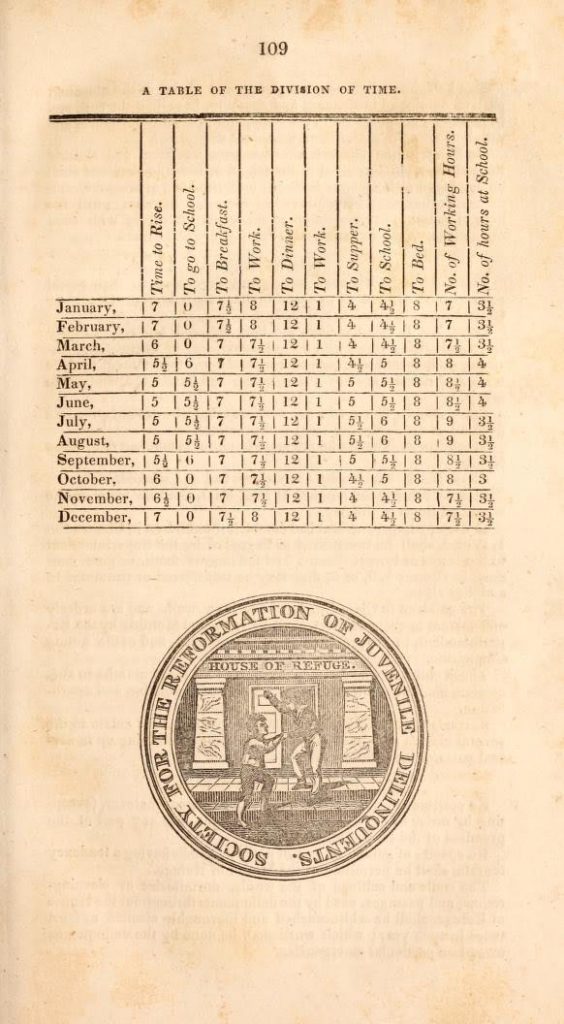

The institution accepted children under the age of 16, referred by the judicial system or their own families, who were rehabilitated through a strict daily program of school, work, and prayer. Their education, managed by five teachers, included instruction in reading, writing, arithmetic, and geography, with occasional music lessons. Religious instruction on the Sabbath was provided by the Chaplain and the Head Teacher. Undoubtedly many of the students had received little or no prior religious instruction, for one teacher of boys, T.C. McKennee, wrote in 1845:

“I had not expected to find, in the nineteenth century, and in the city of New-York, so many children so entirely ignorant of the fundamental doctrines of the christian religion.”

By all accounts, the food at the House of Refuge was nourishing and adequate. The children were fed meat once daily. In 1860, one New York Times reporter commented,

“We are inclined to believe that the food, both in quality and quantity, is better than that of the laboring classes generally.”

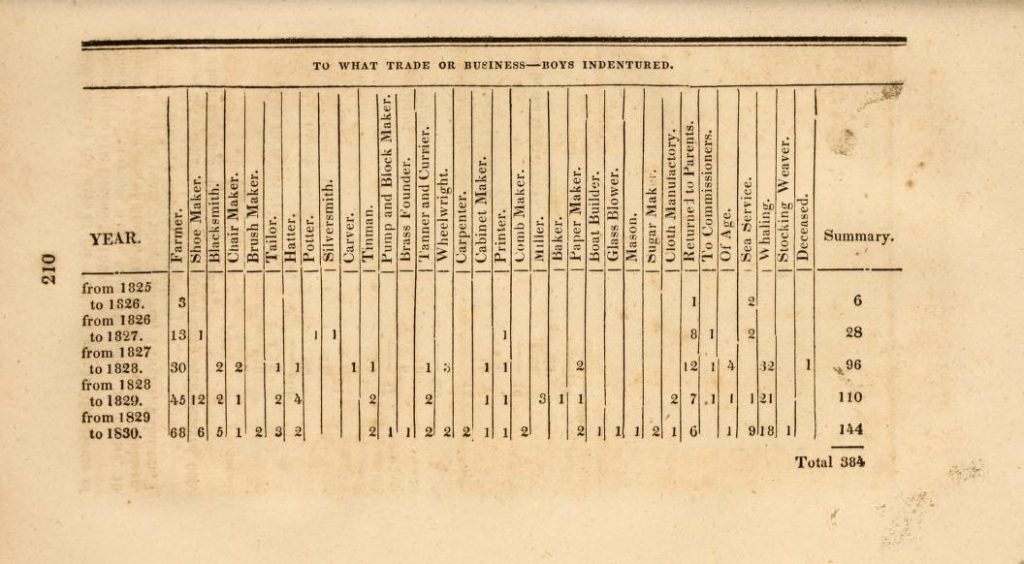

All children admitted to the House of Refuge were “trained in habits of industry.” Boys were instructed in such useful trades as shoemaking, tailoring, and chair caning. Girls learned cooking, sewing, and clothing and bedding manufacturing. Any child who rebelled against the strict rules of the institution (and records indicate there were a good number), or tried to escape was subjected to corporeal punishment: whipping; placement in solitary confinement; and the use of leg irons were commonly employed. Black children were not accepted at the institution until 1833.

Charles Dickens Approves

Visitors to the House of Refuge, including Charles Dickens and Frances Trollope, were greatly impressed with the work of the institution. Dickens, in his American Notes (1842), called it a “noble charity,” and a “meritorious and admirable establishment,” which is “always under the vigilant examination of a body of gentlemen of great intelligence and experience.” Deemed a great success, the institution admitted over 1,678 boys and girls between 1825 and 1835. In 1860 alone, 560 children were in attendance.

.

.

Out into the World

Once deemed “reformed,” a resident was then either apprenticed to a trade or returned to his parents (the latter group being those who were most frequently returned for another round of reform). When discharged to their apprenticeships, residents were given a letter that included the following words of advice:

“If you make yourself master of your business, are diligent in your calling, establish a character for truth, honesty, industry and sobriety, you cannot fail to obtain a comfortable living, and to be beloved and respected.”

The House of Refuge boasted in their Annual Reports that within 3 to 5 years after discharge, 75 percent of those “reformed” were practicing a trade.

Seabury Supports the House of Refuge

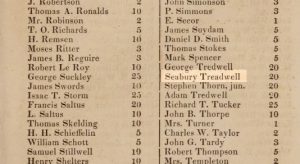

With his donation of $25 in 1824, Seabury Tredwell became one of the inaugural donors to the House of Refuge. For the following three years he, along with his brothers Adam and George, donated $20; thereafter his donation amounted to $5 annually, earning him inclusion on the list of “Life Subscribers and Donors.”

The House of Refuge closed in 1935. As a pioneer in the concept of juvenile reformatories, it made a lasting impact on the juvenile justice system, and in its early years served as a model for the establishment of reformatories in many other American cities.

On February 21, 1852, Miss Susan N., a former resident of the House of Refuge then apprenticed as a domestic servant, wrote the following to her former matron at the House:

“Mr. and Mrs. S use me as their own daughter, and I feel happy. Tell the girls I hope they will listen to all the good advice I know they receive from day to day. As my time is out in about 8 months, I expect to spend Thanksgiving with you in the Refuge, if nothing happens.”

No doubt Miss Susan N. hoped that at the end of her apprenticeship, she would be asked to remain permanently at the home of her employers. I wonder what her options would be if they did not. We have no way of knowing how things turned out for this young girl, but we may imagine that Susan rang in the New Year of 1853 with some measure of happiness in the fact that she had found a situation with a good family who treated her with respect, support, and perhaps even love. May 2017 bring us all as much!

Sources:

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Dickens, Charles. American Notes. New York: John W. Lovell Company, 1842. www.archive.org. Accessed 01/05/17.

- Hart, Nathaniel C. Documents Relative to the House of Refuge. New York: Mahlon Day, 1832. https://archives.org/details/documentsrelativ00soci_0. Accessed 11/14/16.

- Knapp, Mary. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- “Our City Charities: the New-York House of Refuge for Juvenile Delinquents.” The New York Times Archive. January 23, 1860. www.nytimes.com. Accessed 11/14/16.

- Palmer, A. Emerson. The New York Public School. New York: Macmillan Company, 1905. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/3/17.

- Pierce, B.K. A Half Century with Juvenile Delinquents; The New York House of Refuge and Its Times. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1869. www.archive.org. Accessed 11/14/16.

- Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents, N.Y.C. Account Book 1841-1846. New York Historical Society Manuscript Collection.

This has been a fascinating series. Since the material objects and buildings that have been preserved from the nineteenth century generally are representative of the more privileged segment of society, I think it’s easy to get a distorted view of the way it was. These essays help to remind us that most people did not have it as good as the Tredwells! The House of Refuge, while certainly an improvement, sounds pretty grim. Interesting that Seabury Tredwell was involved in the efforts to improve the lot of these children. Love these in depth looks at the Tredwells’ lives.

A terrific series indeed. Too little is known about 19th century philanthropy, which I think of beginning more after the Civil War. Well done, and thank you.

Another wonderful installment in this blog series! I so look forward to each one. Thank you so much, Annie!