“The Hand-Maid of Christianity:” Tredwell Philanthropy, Part 1

by Ann Haddad

| . . |

Abundance Rejoices

.

In one of the memorable scenes in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (published in 1843), Ebenezer Scrooge is visited in his counting-house on Christmas Eve by two gentlemen, who are soliciting funds to “furnish Christian cheer” for the poor and destitute. It is essential to do so at Christmas, when “Want is most keenly felt, and Abundance rejoices.”

The men consult a list, which probably contains the names of the wealthy merchants in the area, who might be encouraged to demonstrate their “liberality,” and dig into their pockets. As we all know, the solicitors are sent out of Scrooge’s office empty handed, for the old skinflint insists that the poor turn to the government run workhouses and prisons, institutions his tax money supports, for assistance.

(Don’t take my word for it: see the Summoners Ensemble Theatre’s production of A Christmas Carol in our own Greek Revival parlor, decorated for the holidays, from December 6-24).

.

.

Growth of Reform

The period of economic growth, industrialization, and massive immigration in New York City following the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 led to a great disparity between the wealthy and the working classes, who struggled to survive amidst rising poverty, crime, and disease. Out of moral obligation, philanthropic reformers, including private, evangelical, and mainstream Christian, sought to provide relief and heal society’s ills by establishing countless charities that supported a variety of social causes, some as a direct response to devastating events. For example, the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis in which many lost their jobs or even their entire fortunes overnight, left over 10,000 unemployed city residents with no recourse but to turn to the Central Committee for the Relief of the Suffering Poor, a newly formed government charity. The efforts proved unsustainable, however, due to the huge numbers of the needy, coupled with the influx of poor immigrants.

During the Christmas season, it was customary for the affluent to lavish gifts not only on family members, but also on the impoverished and overlooked poor. Benevolent societies seized upon the sentiments of gratitude and generosity evoked by the season to promote their causes among the wealthy.

Seabury Was No Scrooge

Had A Christmas Carol been set in New York City rather than London, the two gentlemen in search of donations would surely have visited Seabury Tredwell in his hardware store on Pearl Street. As a prosperous merchant, Seabury would have been included on the potential donor lists of the many charitable organizations that existed in the city. In all likelihood, Seabury would have sent the kindly gentlemen away happy, for research has revealed that he supported several charitable institutions throughout most of his adult life. In light of the the holiday season and its consideration as a time of charitable giving, this three-part blog post will focus on those charities that the Tredwell family supported. The first is the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor.

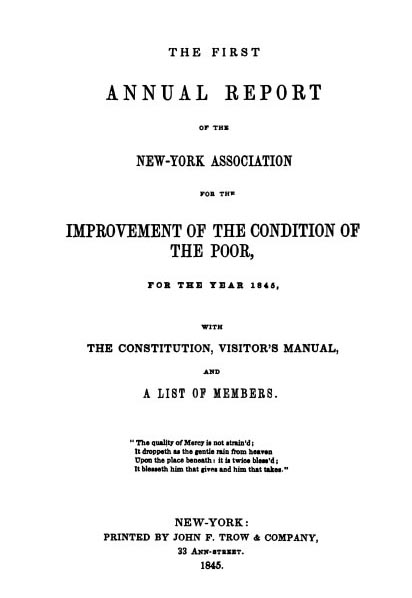

New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor (AICP)

As a reaction to the failures of what they perceived to be defective charitable endeavors, a group of prominent New York businessmen examined the European models of poverty relief. They concluded that due to the lack in oversight of the distribution of charity many imposters were benefitting from the relief intended only for the needy and deserving. In addition, they believed the charitable needed to be educated in ways of giving that would be more beneficial to the recipients.

In 1843, led by Robert Milham Hartley (1796-1881), the group established the New York Association for Improving the Conditions of the Poor (AICP). Hartley believed that the failure of other charitable institutions could be attributed to their lack of discrimination when giving relief; their failure to communicate with one another; and their lack of personal intercourse with the recipients of alms at their homes.

According to its constitution and by-laws, the aim of the AICP was “the elevation of the moral and physical condition of the indigent; and so far as compatible with these objects, the relief of their necessities.” The directors emphasized that charity without moral reform was useless; poverty was the result, not of a failed economic system, but of moral lassitude, which could be rectified by the introduction of values such as self-reliance and pride in one’s efforts; and the promotion of worthy habits such as temperance, industry, and frugality. The AICP devised an elaborate system for the equitable distribution of relief to the “worthy poor.” In this way, they would be able to weed out the fraudulent, or, to separate the “precious from the vile.”

Divide and Conquer

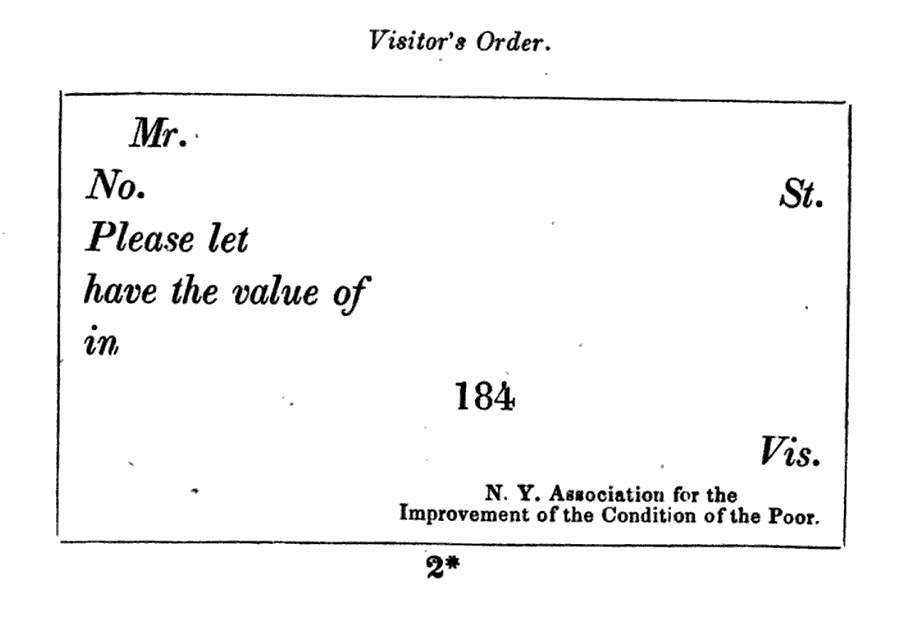

Under the AICP’s organization, the city’s existing 17 wards, or “Districts,” which extended from the Battery to 40th Street, were divided into several hundred sections. Each section had a volunteer “visitor,” who, armed with a “Manual of Rules and Instructions,” was charged with identifying the poor families in need of relief. After ascertaining that the families were truly needy and of good moral character, the visitor was to extend services, provide counsel, and investigate other religious and charitable societies that might be able to assist. Giving money was forbidden, especially to the intemperate. When no other help was available, they were then to draw from the resources of the AICP, but only to purchase food, fuel, or clothing.

Those who failed to pass through the “vast sieve” of necessary criteria to receive assistance were dispatched to the appropriate city agencies. Many of the ill and insane were sent to Bellevue; those who were reconciled to lives of pauperism were sent to the almshouse.

To prevent abuse of the system, the AICP established a central registry of poor families who had received assistance. Visitors were encouraged to engage in “friendly intercourse” with families under their care, and to be an example of the morality they wished the poor to espouse. The AICP described itself as:

“the hand-maid of Christianity, in its endeavors to meliorate the condition of the indigent.”

From 1842-45, the AICP spent nearly $28,000 to aid 8,013 applicants. In addition to the visitor program, it initiated other efforts to improve the conditions in the poor neighborhoods, including the opening of a dispensary, a bathhouse, and a bank. Later reforms focused on children’s health, truancy, the provision of pure milk, and sanitation. In addition, owing to the efforts of member Robert Bowne Minturn, the AICP was one of the early advocates of the development of Central Park.

Seabury Supports the AICP

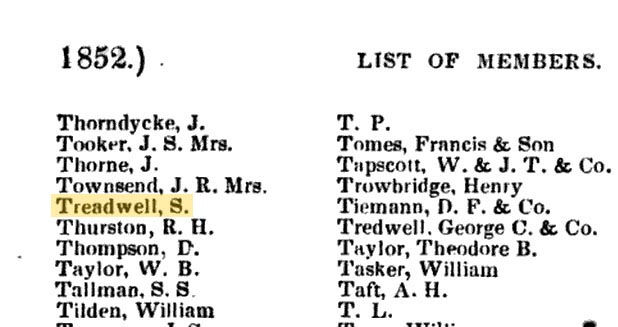

According to the available annual reports, Seabury Tredwell was a member of the AICP, supporting it through monetary donations from 1848 through 1859. His brothers Adam and George Tredwell, who like Seabury were wealthy merchants, were also among the 4,000 contributing members. Membership lists, which read like a Who’s Who of contemporary New York Society, do not include the monetary amount of their donations.

By 1850, the AICP was the most influential charity in New York, and its national renown led to its use as a model for successful charitable reform in many other cities. In 1855-1856, it provided relief to 10,879 families through a total of 43,244 visits. The organization extended its reach to the area of housing reform, opening the Workingmen’s Home on Elizabeth Street in 1855. Described as the earliest “model tenement,” the rental apartments were solely occupied by African Americans, as this group was frequently deprived of adequate housing.

In 1939, the AICP merged with the Charity Organization Society to become the Community Service Society of New York City, which continues its work to this day.

In the AICP Annual Report for 1859-60, a visitor related the story of a destitute woman who, down to “only one dime in the world,” fed herself and her four children. Here are the details in her words:

“Two cents for coke (cheaper than coal)

Three cents for a scraggy piece of salt pork (about 1/2 pound)

Four cents for white beans

One cent for cornmeal

Small as it is, if rightly managed, there is a great deal of eating in one dime.”

Thanks in part to the generosity and benevolence of the Tredwell family, many destitute New Yorkers were provided with relief through the AICP.

Enjoy the holidays! Or, as Tiny Tim exclaimed, “God bless us, everyone!”

Sources:

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Community Service Society. www.cssny.org. Accessed 11/18/16.

- Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843.

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

- New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, Annual Report, 1845-1860. catalog.hathitrust.org. Accessed 11/14/16.

- Spann, Edward K. The New Metropolis: New York City, 1840-1857. New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.

I visited the merchants house last December after reading the book about the treadwell’s. I found the family and the history of the home very interesting and follow the museum on facebook. Thanks for this article it is another exciting piece to the puzzle of how the treadwell’s lived. I am from Alamo Tennessee and have loved each visit I have had to NYC.