“Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing:” Elizabeth Tredwell & Effingham Nichols

by Ann Haddad

Bells Are Ringing!

The magnificent row house on Fourth Street was surely buzzing with excitement on the morning of Wednesday, April 9, 1845, for it marked a Tredwell milestone: the first family wedding! Seabury and Eliza’s eldest child, 23-year-old Elizabeth Seabury, was about to tie the knot.

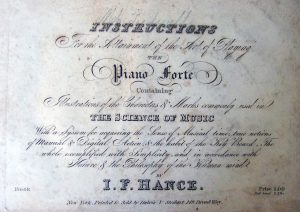

Born on July 23, 1821, in the Tredwells’ first home at 34 Cedar Street, Elizabeth was baptized on August 18 at St. George’s Chapel, then located at Beekman Street. She, like four of her sisters, attended the fashionably elite Mrs. Okill’s Academy, located at 8-10 Clinton Street (now 8th Street). In addition to the usual academic subjects, Elizabeth was instructed in the French language and in music, two skills considered essential to a young woman’s education. The Tredwell Books Collection contains one of Elizabeth’s music books, Instructions for the Attainment of the Art of Playing the Piano Forte, which was most likely also used by her sisters.

The Nichols Family: An Excellent Lineage

Elizabeth’s “finishing school” education was the preparation for the roles she was predestined to assume within the elite society in which she was raised, that of wife and mother. Meanwhile, the young man to whom she would one day be wed was being educated by a private tutor so that he would follow in his father’s footsteps and attend Yale University.

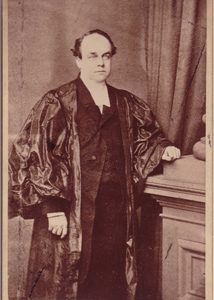

Effingham Howard Nichols, born on November 17, 1821, was surely considered a suitable match for Elizabeth; he came from a prominent New York family, counting among his ancestors Sir Richard Nichols, the first English Governor of New York. His father, Reverend Samuel Nichols, was an Episcopal clergyman and rector of St. Matthew’s Church in Bedford, New York, where Effingham was born. Effingham Howard Warner, his uncle and namesake, was one of the founders of St. Bartholomew’s Church. His mother, Susan Nexen Warner, was the daughter of millionaire George James Warner, who lived on Fourth Street and the Bowery, and owned a substantial amount of property in the neighborhood, including at one time the land on which the Tredwell home was built.

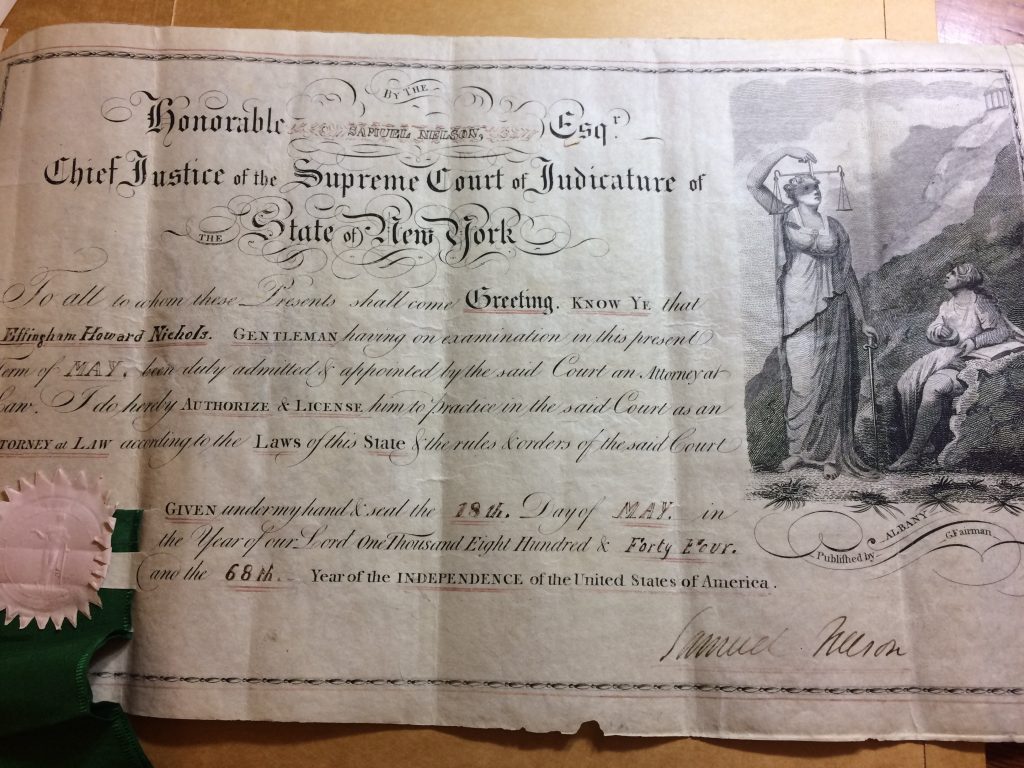

After receiving his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1841, Effingham commenced the study of law, working as a clerk until 1843, when his opened his own law practice at 7 Nassau Street.

A Fashionable Wedding

We do not know when or how Elizabeth was introduced to Effingham. Most likely they met through their parents’ friends or through Seabury’s business associates. Alas, no written record exists of the couple’s courtship and wedding. (For a thorough and revealing discussion of the strict rituals of mid-19th century courtship, see Chapter 9, “A Fine Romance,” in Mary L. Knapp’s An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City,1835-65.)

The couple were wed by the groom’s father on April 9, 1845, at St. Bartholomew’s Church, then located at Great Jones and Lafayette Place. It is likely that after the church ceremony, the Tredwell family hosted a wedding reception for family and friends in their Greek Revival double parlor.

Elizabeth, undoubtedly aware of the new trend begun five years earlier by Queen Victoria upon her wedding to Prince Albert, may have worn a white or cream colored wedding dress. Godey’s Lady’s Book, a popular women’s magazine that was the arbiter of fashion and taste, wrote of the color in 1849:

“It is an emblem of the purity and innocence of girlhood, and the unsullied heart she now yields to the chosen one.”

Custom also dictated the bridal dress be made of satin and the veil be of Brussels lace “… well enough for city drawing-rooms;” the wreath and bouquet be composed of white flowers (although orange blossoms were popular); and white silk stockings and satin slippers finish the bride’s ensemble. Only a wealthy man like Seabury Tredwell would have been able to afford such finery for his daughter.

.

.

The Heiress Is Born!

In keeping with the tradition of the time, wherein newlyweds lived with the bride’s family while the groom established his career, the couple resided with Elizabeth’s parents on Fourth Street. Nine years later, on October 30, 1854, their first and only child, Elizabeth Howard “Lillie” Nichols, was born. Elizabeth was 33 years old. Phebe, one of Elizabeth’s sisters, recounted the birth in a surviving letter to her younger sisters, who were at the Tredwell family farm in Rumson, New Jersey:

“The Doctor came at 8 oc in the morning and did not leave until about 8 in the evening. I suppose you are very anxious to see the little stranger, she looks just like the Nichols light hair fair complexion and long fingers just like her daddy. She is the best little thing, and handsomest little creature you ever saw.”

In the early to mid-19th century it would have been highly unusual that nine years would pass before the birth of a couple’s first child. According to historian Judith Walzer Leavitt, in this period an American woman gave birth to an average of seven live children. As motherhood largely defined a woman’s identity, childlessness was usually explained by the high rate of miscarriage and stillbirth during the Antebellum period.

Real Estate Speculator

In addition to his law practice, Effingham became caught up in the mid-19th century Brooklyn real estate boom, in the area now known as the Fort Greene Historic District. Easily accessible to Manhattan by steamboat, the neighborhood attracted the burgeoning middle-class population who took up residence in the new three and four-story brownstone row houses. Between 1851 and 1859, Effingham bought and sold at least seven properties in the area; in 1859, after living for 14 years under Seabury’s roof, Effingham, Elizabeth, and five-year-old Lillie moved to the Brooklyn neighborhood.

Neighbors of the Astors

Between his real estate investments and his law practice, Effingham must have achieved considerable wealth, for in 1864 he followed other members of the fashionable upper class and relocated his family and four Irish servants to a brownstone at 339 Fifth Avenue, at 33rd Street. Several members of the Astor family, including Mr. And Mrs. William Backhouse Astor II, were neighbors at nearby 350 Fifth Avenue (now the site of the Empire State Building), an address that would become the epicenter of New York society, with Caroline Astor as its Queen.

The Nichols’ Fifth Avenue home was known to many Yale graduates for its warm and generous hospitality, for Effingham, described by his colleagues as “a delightful host and companion,” was devoted to his Alma Mater and served actively on the Fairfield County Alumni Association of Yale University. Sadly, the Nichol’s home was one of three brownstones torn down in 1890, nine years after Effingham sold it.

Railroad Baron

Beginning in 1865, Effingham switched his career path from personal law to corporate counsel for the Pacific Railroad and other large railroad enterprises. His involvement, from 1867 to the spring of 1873, necessitated him spending a large portion of his time in Washington, D.C. He had become a wealthy financier with an outstanding reputation among his peers as “a man of force, who strongly influenced his business associates.”

In his later years, Effingham sold his railroad interests to devote more time to real estate law, and to the management of family interests, notably, the settlement of Seabury’s estate.

Country and City Pastimes

The Nichols family, in addition to spending summers at Greenfield Hill, Connecticut, where Effingham’s extended family resided, vacationed at Leland House, a grand hotel on Schroon Lake in the Adirondack Mountains. They clearly left their mark on the town. Effingham was instrumental in the building of St. Andrew’s Chapel, serving as a warden from its founding in 1880 through at least 1885. He also financed the building, in 1870, of the “Effingham,” the first steam-driven commercial freight and passenger boat on Schroon Lake. In the Adirondacks, Effingham cultivated a deep love of the natural world. He also possessed an artistic nature, and was an occasional writer of prose and poetry. In New York City, he was a member of the Union League Club and the London Society of Science and Art, and a Fellow of the National Academy of Design.

Elizabeth’s Health Fails

The frequent trips to Schroon Lake were most likely attempts to restore Elizabeth’s health. We do not know when she developed the chronic bronchitis that would eventually take her life. A letter from Effingham to his father, dated July 27, 1873, from the Adirondack Mountains indicates that at age 52 she was already ill:

“Elizabeth I think is improving a little. Her fever has left her. But her cough still continues.”

In another undated letter, Effingham expresses growing concern about Elizabeth:

“Early in the evening the Doctor (Horne of NY) thought she might not live through the night. But she has rallied some and now he thinks we may be able to move her to NY if she continues to rally for three or four days. Poor Lillie has ten times the nerve that I have. It is very sad indeed.”

“A World of Sorrow”

In 1878, writing to Elizabeth’s sister Julia from Schroon Lake, Effingham’s tone is despairing and melancholy:

“Elizabeth is very, very weak. It is very doubtful about being able to move her. This is indeed a world of sorrow.”

Elizabeth was 58 years old when she died on January 7, 1880, at her home at 339 Fifth Avenue. She was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Lillie was 25 years old at the time of her mother’s death.

In October 1881, Effingham wed Caroline Robins of Metuchen, New Jersey. He and his new wife moved to 620 Fifth Avenue, at 50th Street, and then in 1895 to Park Avenue and 75th Street, where he lived until his death. He died at the age of 77 on November 4, 1899, at his summer home in Greenfield Hill, Connecticut.

Lillie never married; she died in 1944 at the age of 90. It was she who inherited the Tredwell home on Fourth Street after her aunt Gertrude’s death; she then sold it to George Chapman in 1934. Thus the Merchant’s House Museum was born.

Reflecting on his life in an essay published in University Magazine in 1892, Effingham wrote:

“Providence has thus far dealt gently with me. I have met with fortune and misfortune, with days of sorrow and days of rejoicing; but my blessings have been greater than I deserved.”

A Lasting Union

Although we have no written testimony that sheds light on the marriage of Elizabeth and Effingham, it is apparent from his letters and work on their behalf that Effingham bore deep affection and concern for his wife and her family. The marriage, ended only by death, lasted 35 years.

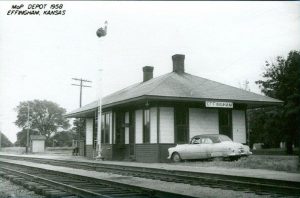

In 1868, Effingham Howard Nichols had had the distinction of having a town, Effingham, Kansas, named in his honor. As a promoter of the Central Branch Union Pacific Railroad, he was instrumental in the growth of the town. Effingham no doubt was privileged to name at least three of the streets, for they bear the names Seabury, Howard, and most endearingly, Elizabeth.

Sources:

- ancestry.com. U.S. Newspaper Extractions from the Northeast, 1704-1930. New York Evening Post, 11 April, 1845. Accessed online 3/30/17.

- ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995. Accessed online 3/30/17.

- Godey’s Lady’s Book. “Etiquette of Trousseau,” August, 1849. www.godeysladysbook.com. Accessed online 4/3/17.

- King, Greg. A Season of Splendor: The Court of Mrs. Astor in Gilded Age New York. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009.

- Knapp, Mary. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- Levitt, Judith Walzer. Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America, 1750-1950. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Fort Greene Historic District Designation Report. September 26, 1978. www.nyc.gov/html/lpc/downloads/pdf/reports/FortGreene_DR.pdf. Accessed online 3/31/17.

- Nichols Family Papers, 1810-1833. Manuscript Collection, New-York Historical Society.

- Post-Standard, 28 September 1972, p. 30. www.newspapers.com. Accessed online 4/4/17.

- Proceedings of the New York State Bar Association. Albany, New York, January 15-16, 1901, p. 364. Accessed online 4/4/17.

- Town & Country, Vol 79, p.14., September 1, 1922. Accessed online 3/29/17.

- Yale University. Obituary Records of the Graduates of Yale University Deceased from June,1890 – June, 1900. New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1902, p. 672. Accessed online 3/29/17.

- Yale University. University Magazine, Vol. 4, 1892, p. 49-51. Effingham Nichols File, Merchant’s House Museum Archives.

- Yale University Class of 1841. Semi-centennial Historical and Biographical Record. New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1892, p.152-156. Accessed online 3/29/17.

So interesting. These individual lives are typical of New Yorkers of their social class and time. This is wonderful research and a great addition to the history of the Merchant’s House.

[…] April 7, 1845, Elizabeth married Effingham Nichols (see our April 2017 blog post, “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing: the Marriage of Elizabeth Tredwell and Effingham Nichols”). We do not know when and how Elizabeth and Effingham met, nor are we aware of the length of their […]

[…] 1851; by 1859 he owned at least seven properties in the neighborhood. (See my post of April 2017, “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing”). In addition, one of his brothers, William B. Nichols, owned houses near Seabury’s property on […]