“The Destroying Angel:” New York’s 1832 Cholera Epidemic

by Ann Haddad

Disturbing News

In the harsh winter of 1831-32, Seabury Tredwell had cause for alarm. As he conducted his business at the seaport and in his warehouse on Pearl Street, he could not have avoided the terrifying news. It was spoken of at every turn, and reported daily in the newspapers: “King Cholera” was heading west! By mid-June, after cutting a path of death as it traveled west from India through Europe, cholera had crossed the Atlantic and reached Canada. If Seabury had kept a journal, most likely he would have written words similar to those of the former New York mayor and diarist Philip Hone, whose entry on June 15 reads:

“It [cholera] must come, and we are in a dreadful state to receive it.

The city is in a more filthy state than Quebec and Montreal.”

A Seaside Retreat

As the result of 20 years as a successful hardware merchant, Seabury enjoyed wealth, success, and prestige. The economy was booming, and Seabury’s prosperity put him solidly in the elite merchant class. He had a comfortable home on Dey Street to accommodate his wife and five children. Yet the city was changing. The continued commercial growth, and the sudden influx of immigrants, who often had no choice but to accept low-paying jobs, resulted in overcrowding, poverty, and poor sanitation. Many of Seabury’s colleagues had already moved north to escape the congestion of downtown.

As the cholera approached, Seabury no doubt thought long and hard about how to ensure the health and safety of his growing family. Unlike many in his circle, he had yet to acquire a country retreat. During the summer of 1832, familial concern must have driven Seabury to either his family farm in West Hempstead, Long Island; or perhaps he had learned by that time of a property in Black Point, New Jersey, later known as Rumson. A pleasant steamboat ride led to a 650 acre farm, and surroundings that were ideal: fresh air, clean water, sea breezes, and all a safe distance from the city’s dangers. He officially purchased the property on September 17 for $13,000.

Fertile Ground for Cholera

Although New York City had endured several epidemics prior to 1832, cholera was a stranger to its shores. Yet, its 250,000 inhabitants knew the city was ripe for it. The heaps of garbage, mud, and animal excrement that filled the streets were nicknamed “Corporation Pudding” by the residents, whose own overflowing privies contributed to the noxious vapors, or “miasma,” that clouded the air. The water from city wells was tainted; only the poor, who could not afford to purchase spring water from outside the city, drank it. During the cholera epidemic, they did so with fatal results.

The tightened ships’ quarantine enacted in the winter of 1831-32 by Mayor Bowne limited Seabury’s access to the goods he was shipping and receiving. The quarantine was ineffective in preventing the arrival of cholera, however, because ships carrying passengers entered through the back door of nearby ports, such as Perth Amboy, and their customers boarded ferries to New York without any resistance from authorities.

Cholera? Where??

The 10-year absence of any epidemic had lulled the Board of Health into a state of almost total indifference. The Board was considered to be a reactionary one, coming alive only in view of an imminent threat. Medical knowledge was sorely primitive, and physicians lacked the resources needed to combat such an onslaught. Merchants knew that epidemics were bad for business (one group calculated they would lose $3,000-$5,000 per day), and pressure from them no doubt contributed to the Board’s slow response to the outbreak.

City government remained silent as the threat of cholera loomed. Finally, on June 4, the City Council enacted legislation to regulate the cleaning of the city streets. But it was too little, too late. After the work was done, residents reacted with astonishment:

“I never knew that the streets were covered with stones before. How very droll!”

Cholera Strikes

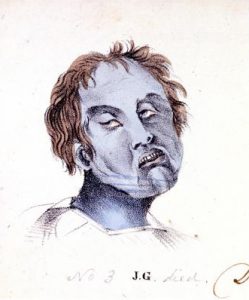

Vibrio cholera, the bacterial organism that causes cholera, is spread through contaminated body fluids, which, due to poor sanitation, can be found in shared food and water supplies. As the discovery of germ theory and knowledge of contagion were years away, cholera’s etiology was unknown; its violent, acute onset and horrifying symptoms were terrifying to witness. Profuse diarrhea preceded severe vomiting, dehydration, a sunken appearance, and a bluish tinge to the skin. The unquenchable thirst led victims to scream for water; and uncontrolled spasms that wracked their bodies in the final stages were excruciatingly painful. Death occurred in a matter of hours.

In June, several physicians began to note the increasing number of patients with symptoms of cholera, and they begged city officials to alert the public and to take action. Dr. John Sterns pleaded:

“I see nothing but impending ruin unless the great spread of new cases would

convince the Board of the existence of the disease and verify my predictions.”

.

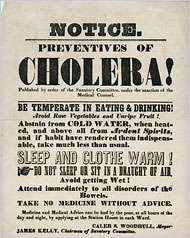

On July 2, the news exploded: the first case of cholera in New York City had finally been confirmed. Panic ensued. The following day, the Board of Health formed a medical committee to track and report the daily spread of the disease. The Special Medical Council, consisting of seven prominent city physicians, drew up a list of recommendations for the prevention of cholera, which was distributed in handbills and published in the city newspapers. The normally raucous Independence Day celebration, as reported by Philip Hone, was non-existent.

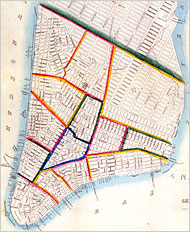

Within several weeks, city officials established 5 emergency cholera hospitals in schools and other buildings. The ferocious spread of cholera that battered the city left physicians overwhelmed. The epicenter of the epidemic was the 6th Ward, which included Five Points, the notorious slum inhabited largely by African-Americans and Irish immigrants. On July 20 alone, at the height of the epidemic, 100 cases were reported.

Disgusted by the indifference of city agencies, a group of benefactors decided to take action to assist those devastated by the epidemic. At a meeting held at the Merchants’ Exchange on July 16, 1832, a new Committee of the Benevolent was formed, and raised thousands of dollars over several days. N.&H. Weed, a store located at 191 Pearl Street, was one of many throughout the 15 wards designated as a food and clothing collection site.

Chances are, by the time cholera activity peaked, the Tredwell family, like most other wealthy New Yorkers, was long gone. Another Pearl Street merchant took the time, before fleeing, to post on the door of his shop:

“Not Cholera sick, nor Cholera dead,

But from the fright of Cholera fled-

He’ll quick return, when Cholera’s over,

If from the fright he should recover.”

.

The Scourge of God

Church leaders looked upon the epidemic as the work of a wrathful God, and seized the opportunity to call for repentance for the sins that had surely caused the cholera. Reverend Gardiner Spring preached:

“We have seen the destroying angel execute the sentence of heaven upon a guilty people.”

.

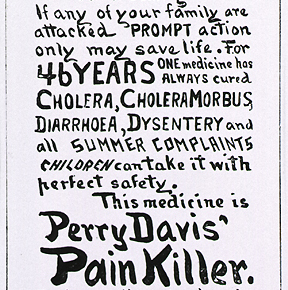

Ineffective Treatments and Quackery Rule

Both physicians and the affluent favored the theory that cholera struck the poor, the intemperate, and the immoral. But the pattern of the disease proved them wrong, as it spread outward from the 6th Ward into the wealthier neighborhoods. The “remedies” employed by physicians included laudanum; bloodletting; and hot brandy, infused with cloves or cayenne pepper. External applications included flannel dipped in hot brandy or turpentine; and mustard plasters. Quackery abounded. All of these “cures” failed. Undertakers could not bury the bodies fast enough, and they remained piled up in the street. Finally, one physician gave the following advice to anyone who had to care for a victim:

“Always employ Women, rather than Men, they are more tender,

more alert and infinitely more self-possessed.”

.

The End of the Epidemic

In August, as the number of cases began to decline, the refugees returned, businesses reopened, and life resumed much as it had been before. By September it was over, but not before the death toll had reached 3,515. Once the danger was passed, the Board of Health resumed its passive role. Two more epidemics would strike New York City before officials discovered how to contain cholera. It would be another 17 years before Dr. John Snow, a British physician, proved that cholera was spread by contaminated water. Owing in large part to his likely escape to Rumson in the summer of 1832, Seabury Tredwell and his family were spared the anguish of cholera.

SOURCES:

- Albion, Robert. The Rise of New York Port [1815-1860]. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1939.

- Atkins, Dudley, M.D., Ed. Reports of Hospital Physicians, and other documents in relation to the Epidemic Cholera of 1832. New York: G&C.&H. Carvill, 1832.

- Gabrielan, Randall. Rumson: Shaping a Superlative Suburb. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

- Gilman, C.R., MD. Hints to the People on the Prevention and Early Treatment of Spasmodic Cholera. New York: Charles S. Francis, 1832.

- Greene, Asa. A Glance at New York. New York: A. Greene, 1837.

- Cholera File, 1832. Board of Health MSS. Municipal Library, New York City Department of Records.

- Minutes of the Board of Health, September 6, 1831. MSS. City Clerk’s Papers, Municipal Archives and Records Center.

- New York Evening Post, various dates: February-September, 1832. www.newspapers.com. accessed 7/6/16.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Cholera Years. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Spring, Gardiner, D.D. A Sermon, Preached August 3, 1832, A Day Set Apart in the City of New- York for Public Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer on Account of the Malignant Cholera. New York: Jonathan Leavitt, 1832.

- Sterns, John, MD. Concerning the Cholera Epidemic. MS 170, 1832, The New York Academy of Medicine Library Manuscript Collection.

- Students of Rumson High School. History of Rumson, 1665-1944. Rumson, NJ: The Historical Committee, 1944.

- Tuckerman, Bayard, ed. The Diary of Philip Hone. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1889.

Thank you, Ann, for this! Extraordinary research and so interesting! This is the sort of thing that is drained from our collective memory of those times, I’m afraid. It’s so good that you have brought it to our attention. And I believe that there is enough here that we can now make a legitimate inference that Seabury Tredwell did buy the Rumson property in response to the cholera epidemic. This article is worthy of publication beyond the Merchant’s House blog. Don’t know where, but there must be some place.

Excellent work in every respect, Annie. I second Mary’s belief that this deserves wider distribution.

My great-great grandparents died in the cholera epidemic in New Jersey. My great-grandfather was raised by another family, so we are not certain if the surname was “Boyd” or “Wright.” Is there a list of people who died from cholera after April 1832? I have the Patterson list for 1832-1833.

Hello,

The NJ Municipal Archives may be useful. The NYC Municipal Arcives contain original records of the cholera victims, including those hastily scrawled lists kept by the physicians who treated them. Good luck with your research!

New York’s 1832 Cholera Epidemic is well documented in the Christian Intelligencer (New York) by Reformed Church in America which is on archive org

I was looking for my great grandfather who was in the 1831 city directory and in 1832 year my grandmother as listed as a widow… the newspapers start in Aug 1831 – July 1833. Great collection for the time frame.

Title: Christian intelligencer

Author: Reformed Church in America. General Synod

Author: Reformed Protestant Dutch Church (U.S.)

Note: New-York [N.Y.] : Printed and published by William A. Mercein for an association of members of the Protestant Reformed Dutch Church, 1830-1920