“My Conscience Acquits Me:” The Scandal of Bishop Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk

by Ann Haddad

A 19th Century Church Scandal

Although the phrase “sexual harassment” did not come into popular use until the mid-1970s, accusations of mistreatment and abuse by women against men of power have been part of the historical record for centuries. In November 1844, such a charge was brought against one of the most powerful men in New York, the Reverend Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk, then Episcopal Bishop of New York. The scandal, trial, and media circus that ensued in New York no doubt rocked the Tredwell family’s world, for Bishop Onderdonk was a relative (first cousin once removed) of Seabury Tredwell.

Breakfast with George

The name Onderdonk carried considerable cache in early 19th century New York. Many New Yorkers were likely familiar with the story of Hendrick Onderdonk (1724-1809), the enterprising grist mill owner of Roslyn, Long Island, who in 1773 established the first paper mill in Hempstead Harbor, and who once welcomed a famous guest to his table. On April 24, 1790, President George Washington wrote in his diary:

“Left Mr. Yooung’s before six on Saturday., and passing Mosquito Cove, breakfasted at Mr. (Hendrick) Underdunck’s [sic], at the head of a little bay [Hempstead Harbor] where we were kindly received and well entertained. This gentleman works a grist and two paper mills, the last of which he seems to carry on with spirit and for profit.”

| … |

.

A Star is Born

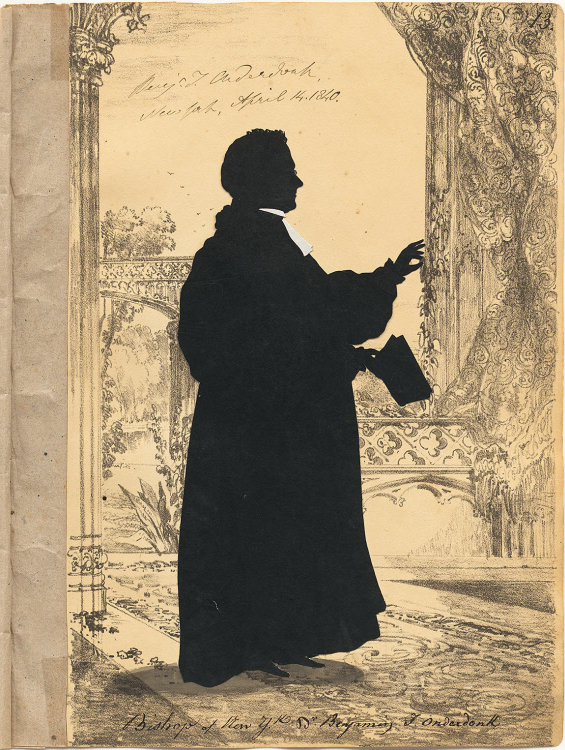

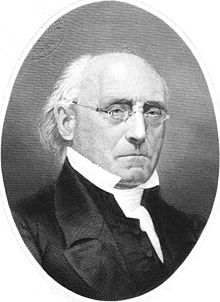

Hendrick Onderdonk’s son, Dr. John Onderdonk (1763-1832), was a distinguished physician in New York City for over 50 years, a vestryman of Trinity Church until his death, and at one time President of the Medical Society of New York. On July 15, 1791, his wife Deborah gave birth to a son, Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk, who would go on to have an illustrious career in the Episcopal Church, until it was suddenly destroyed by scandal.

Benjamin graduated from Columbia College in 1809 (his older brother, Henry Ustick Onderdonk (1789-1858), was a physician and churchman who became Assistant Bishop of Pennsylvania in 1827). Because there were no seminaries in the country at the time, he was trained for the ministry by his mentor and then-Bishop of New York, John Henry Hobart. In 1813, he married Eliza Handy Moscrop (1793-1887); she bore him seven children. The family resided for many years at the Episcopal Residence at 106 Franklin Street, then (as now) considered a chic neighborhood in the city.

.

A Home in Trinity Church

After his ordination in 1815, at the age of 23, Bishop Onderdonk was appointed Assistant Minister at Trinity Parish in New York City. In the ensuing fifteen years, as he advanced his career in church administration, he earned a reputation for his superior knowledge of canonical law, his devout nature, his dedication to the poor, and his excellent managerial skills. His academic appointment was as Professor at the General Theological Seminary in what is now the Chelsea neighborhood.

Fourth Bishop of New York

Upon the sudden death of his mentor, Bishop Hobart, in September 1830, Onderdonk was elected as his successor, becoming the Fourth Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York. He was consecrated on November 26, 1830, in St. John’s Chapel on Varick Street. The Tredwells, who lived on Dey Street at the time, very likely were present to witness the bestowing of this prestigious honor upon their cousin.

Bishop to a Growing Church

During his episcopate, Bishop Onderdonk established many new parishes, and supported missionary work in central and western New York State. Aware of the increasing disparity between the wealthy (who paid huge sums for the purchase of a pew) and the working poor, who by virtue of their poverty were excluded from worship, he spearheaded the creation of the Protestant Episcopal City Mission Society in 1831. The rapid growth of the Church in the state awakened the realization that one Bishop could not possibly supervise the entire Diocese; hence the formation of the Diocese of Western New York in 1838.

Bishop Onderdonk officiated at the marriages, baptisms, and funerals of the elite in New York. On June 26, 1844, just months before he was embroiled in scandal, he officiated at the wedding of President Tyler and Miss Julia Gardiner at the Church of the Ascension on Fifth Avenue at 10th Street.

| … |

The Oxford Movement

The tide began to turn against Bishop Onderdonk during the 1841 General Convention of the Episcopal Church, in which he voiced his support of the Oxford Movement, which promoted the reinstatement of older traditional Christian beliefs in the teachings and liturgy of the Church of England. In a speech given at the convention, Onderdonk advocated “a return to Christ – to the principles, faith, and order of His One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church.” Objections from certain members of the Episcopal clergy, many of whom felt threatened by the steady growth of the Catholic population, poured forth unceasingly. Bishop Onderdonk was now viewed negatively as the leader of the Oxford Movement; yet he had the full support of the popular Reverend Samuel Seabury, then Rector of the Church of the Annunciation on 14th Street. (This Rev. Samuel Seabury was the grandson of Seabury Tredwell’s uncle, also named Samuel Seabury. See Uncle Sam(uel): Bishop, Loyalist … Broadway Star? for more information on the original Rev. Seabury.)

The Carey Ordination

The outcry against the Oxford Movement (and subsequently Bishop Onderdonk), reached its peak in 1843, when he supported the ordination of Arthur Carey, a shining star at the General Theological Seminary. Despite objections from other Church leaders that Carey’s views were too sympathetic to Roman Catholicism, and ignoring the loudly voiced protestations of two rectors (Dr. Hugh Smith of St. Peter’s and Dr. Henry Anthon of St. Mark’s in the Bowery, who interrupted the ceremony by reading a formal protest aloud), on July 2, 1843, Bishop Onderdonk admitted Arthur Carey to the deaconate.

The Rumors Begin

As a result, a bitter assault was waged on Bishop Onderdonk in both the religious and secular press and in private meetings in New York. Meanwhile, unpleasant rumors began circulating – largely due to the efforts of Reverend James Richmond of Rhode Island (who himself often displayed, according to the Bishop, “erratic peculiarities,” and whose writing appears clearly to be the rumination of a troubled mind), that the Bishop was a drinker who had on more than one occasion acted indecently with women. The Bishop’s coarse manner and easy familiarity had often been remarked upon; it was a short hop from that to accusations of impropriety. Declaring, “I am going to Philadelphia to overthrow the Bishop of New York,” Richmond traveled to the convention on October 14, 1844, armed with affidavits signed by four women who claimed to be victims of Bishop Onderdonk’s indiscretions, and presented them at the General Convention held in Philadelphia.

“Buried Alive”

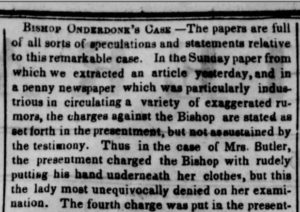

On November 7, 1844, after clergymen in Bishop Onderdonk’s own diocese of New York turned their backs on the charges that were made against him, three evangelical bishops from remote dioceses (William Meade of Virginia, Stephen Elliott, Jr. of Georgia, and James H. Otey of Tennessee) made formal charges against Bishop Onderdonk, accusing him of acts of “immorality and indecency.” The women involved, who were “virtuous and respectable ladies,” testified that the Bishop touched them inappropriately; his accusers stated that he “thrust his hands into her bosom,” and “‘impurely and unchastely’ passed his hand down and along the person and the legs of the said lady.” During one incident that supposedly took place in 1842, he “passed his hand in the most indecent manner down her body, so that nothing but the end of her corset-bone prevented his hand from being pressed upon the private parts of her body …” Bishop Onderdonk was said to be under the influence of “spirituous liquors” during several of the episodes. The incidents, which allegedly occurred between 1837 and 1842, took place while the Bishop was carrying out the duties of his office. The Reverend Samuel Seabury, a close friend, later stated that Bishop Onderdonk was “buried alive” by his own Church.

The Bishop Denies the Charges

Bishop Onderdonk, alerted to the tenor of the affidavits by three friends who were given access to them, stated that the affidavits contained “misrepresentations and gross exaggerations.” He learned that the laity had investigated rumors against him, and “calling on families where they had reason to hope they might hear something to my disadvantage.” The bishops, in their reply to this, stated that they “have not been collecting, but receiving and sifting testimony.” He accused the bishops of “malicious intent;” and stated that the appointed rumor mongers “have done more to bring public scandal on the church than all else connected with this business.”

Bishop Onderdonk did admit that his “habit of reciprocating friendly affection” was carried too far, and as a result “exaggerations and distortions have turned to ill what was really so neither in intent nor in deed.”

On Everyone’s Lips

The New York newspapers and others further afield published daily accounts of the trial. Opinions both in support of and horrified by the Bishop’s charges came from every quarter. According to the New York Daily Herald (January 1, 1845):

“The trial of Bishop Onderdonk now supersedes everything else. Even dandies stop on Broadway to lisp out, “anything new from St. John’s today?” and among our fashionable ladies “how is our dear man coming on?” or “what will be done with the old sinner?”

| … |

Guilty

Despite Bishop Onderdonk’s pleas for an opportunity to defend himself, the presiding bishops refused to share the affidavits with him, thereby keeping him in ignorance of both the charges and his accusers. From December 10, 1844, to January 2, 1845, the Court of Bishops held a trial at St. John’s Chapel. To the astonishment of many, Bishop Onderdonk was found guilty of eight charges by 11 out of 17 bishops. After the verdict was announced, he was summoned to appear before the Court; his denial was brief:

“I … do now protest, before Almighty God and this Court, my entire innocence of all impurity, unchasteness, or immortality …”

.

Despite Evidence to the Contrary

In an article in The Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church (March 1940), E. Clowns Chorley pointed out several facts that bring the charges against Bishop Onderdonk into question. Many of the charges were based on heresay; in one case husband and wife offered contradictory testimony; the circumstances of the alleged acts made it improbable that they took place; and Bishop Onderdonk was received as a guest at the home of his accusers long after the alleged events took place. Reverend Seabury, in his defense of the Bishop, pointed out that the verdict of the Court “was not unanimous: six of the Bishops wholly exonerated him from the charges of which the majority convicted him.”

Bishop Onderdonk’s only rebuttal to the verdict came in the form of a pamphlet, published on January 15, 1845, in which he methodically refuted every charge made against him.

Fake News

In a review of the case in the New York Herald (January 7, 1845), a particular passage resonates today, “It is well known to the community at large … that the clergy of all denominations claim a monopoly of every thing like virtue … and it is usually coupled with a condemnation of all those public institutions … which are likely to come into collision with the pulpit … We have often seen … with what violence the clergy of the Episcopal Church … have assailed the public press, falsely representing it as evil … they have inveigled against the indecencies of the newspapers, and have labored hard to show that its conductors are the most worthless and corrupt men in existence. The truth is, that there is a vast amount of hypocrisy, immorality, and impurity in the ranks of the clergy.”

The Court of Bishops, much to the horror of Bishop Onderdonk’s supporters, published the proceedings of the trial, which sent tongues wagging with fervor. In a letter dated January 19, 1845, Helen Griswold wrote wryly to her husband:

“I understand that they are endeavoring to suppress the publication of Bishop Onderdonk’s trials, and it is thought that he will soon be restored, and that the statements have been misrepresented, I am sure that no lady would come forward publicly with such accusations unless they considered it an honor, and I am confident that he would never have taken such liberty unless he had reason to suppose they were willing. I cannot imagine for an instant how any delicate female could come forward with such statements …”

| … |

Punishment

Because Bishop Onderdonk refused to resign, fearing that it would be interpreted as an admission of guilt, he was suspended indefinitely from the office of Bishop, and from all functions of the Sacred Ministry in the Episcopal Church. He was kept on salary, however, and paid $2,500 annually until his death. He also was permitted to receive Communion. Until 1852, the Diocese was governed by an Ecclesiastical Authority made up of the Standing Committee of the Church. That year, Mayhew Wainwright was elected Provisional Bishop of New York.

The decision of the Court of Bishops was final. The Church had provided for no appeal; and although urged to appeal to a civil court, Bishop Onderdonk steadfastly refused, as he maintained that the ultimate authority in the case lay with the Church.

How Did the Tredwells React?

We have no record of how the Tredwells viewed the accusations, the public trial, and the subsequent disappearance of Bishop Onderdonk from the Episcopal community in New York City. Did they distance themselves from the scandal? One wonders if Bishop Onderdonk had been expected to officiate at the wedding of Elizabeth Tredwell and Effingham Nichols, which took place in April 1845. Having his cousin, the Bishop of New York, officiate at his daughter’s wedding would certainly have been a social coup for Seabury. The disastrous turn of events, however, barred the Bishop from performing church duties, including marriages; perhaps this is what led the Tredwells to ask Reverend Samuel Nichols, the father of the groom, to officiate at Elizabeth’s wedding.

Attempts at Restoration

Between 1847 and 1859, several attempts were made by Episcopal clergy to remit the sentence and restore Bishop Onderdonk to his office; clemency was never granted. In an anonymous letter to the editor of The New York Times (September 17, 1859), a supporter pled:

“Strangers took the Bishop away from us. Let them restore him…the Diocese of New-York is good enough to take back the penitent, and strong enough to sustain itself in so doing”

Following his public humiliation, Bishop Onderdonk lived in seclusion at his home on Franklin Street, and after 1859, at his home at 35 West 27th Street. He attended church daily and took Communion at the Church of the Annunciation, then located on West 14th Street, where his close friend, Dr. Samuel Seabury, was rector. He never publicly expressed bitterness towards his accusers.

Among those who visited him on his deathbed, in April 1861, was Professor Clement C. Moore, whom he had not seen in 14 years. He maintained his innocence until his death:

“Of the crimes of which I have been accused and for which I have been condemned, my conscience acquits me, in the sight of God.”

“A Burning and Shining Light”

Bishop Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk died on Tuesday, April 30, 1861, at the age of 70, and in the 49th year in his ministry. His funeral was held one week later on May 7, at Trinity Church. The throngs of people in attendance spilled into the street; and hundreds of clergymen participated in the service. Twelve pallbearers accompanied the coffin (could Seabury Tredwell have been one of them?); mourners included the students of the General Theological Seminary and children of Trinity School. The entire church was draped in black. Written accounts of the service describe the moment when the coffin was laid in the aisle, “the sun burst forth from a previously clouded sky, and lit up the entire church.” Reverend Seabury, a stalwart champion of the Bishop through his ordeal, claimed in his eulogy that he had “never known the Bishop to utter anything that he should have been unwilling the angels of God should hear, or that he would wish unsaid at the Day of Judgment.” He quoted scripture (John 5:35): “He was a burning and a shining light, and ye were willing for a season to rejoice in his light.”

Bishop Onderdonk is buried within a stone sarcophagus at Trinity Church; it depicts him lying in repose, yet crushing a serpent – “Scandal” – beneath his heel.

Sources:

- Chorley, E. Clowes. “Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk, Fourth Bishop of New York.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Historical Society of the Episcopal Church: Vol. IX, No. 1, March, 1940. https://www.jstor.org./stable/42968753. Accessed 10/30/18.

- Churchman’s Monthly Magazine. Vol 4, 1857, p. 384. books.google.com. Accessed 10/31/18.

- Griswold, Helen Powers. Letter, 19 January, 1845. www.florencegriswoldmuseum.org.

- “Henry M. Onderdonk – Editor of the Hempstead Inquirer.” Friday 29 July, 2011. westhempsteadnowandthen.blogspot.com Accessed 9/29/18.

- Lowndes, Arthur. Archives of the General Convention, Volume VI, May, 1808 to February, 1811. New York: Privately Printed, 1912, pp. 456-468. books.google.com. Accessed 10/23/18.

- New York Daily Herald. 1 Jan 1845, p. 2. newspapers.com. Accessed 10/30/18.

- New York Herald. 5 January, 1845, p. 2. newspapers.com. Accessed 9/19/18.

- New York Daily Herald. 7 January, 1845, p. 2. newspapers.com. Accessed 10/30/18.

- New York Tribune. 27 June, 1844, p. 2. newspapers.com. Accessed 9/19/18.

- Onderdonk, Benjamin Tredwell. A Statement of Facts and Circumstances Connected with the Recent Trial of the Bishop of New-York. New York: Henry M. Onderdonk, 1845. cataloog.hathitrust.org. Accessed 9/19/18.

- Onderdonk, Elmer. Genealogy of the Underdone Family in America. New York: Privately Printed, 1910. www.archive.org. Accessed 10/29/18.

- Protestant Episcopal Church of the United Staes, Court of Bishops. The Proceedings of the Court Convened Under the Third Canon of 1844, in the City of New York. New York: D. Appleton, 1845. catalog.hathitrust.org. Accessed 9/19/18.

- Richmond, James C. The Conspiracy Against the Late Bishop of New-York. New York: James C. Richmond, 1845. Project Canterbury. www.anglicanhistory.org. Accessed 10/30/18.

- Seabury, Samuel, D.D. Witness Unto the Truth: A Sermon Preached in Trinity Church, New York, on Tuesday May 7th, 1861. New York: Mason Brothers, 1861. books.google.com. Accessed 10/30/18.

- Trow’s New York City Directory, 1853-1861. catalog.hathitrust.org. Accessed 10/31/18.

What a fascinating, moving & well researched story.

Thank you!

What incredible research, and such an interesting look at a historical scandal!

I especially love how you brought the Tredwells in at each stage, to remind us that they may have been present and affected!

Thanks, Jackie! We can only imagine the Tredwell family’s reaction, but it must have been a huge blow!

Your fascinating blog post raises so many issues that remain pertinent, Annie. The bishop seems to have been tried and convicted right from the start, both in the court of public opinion and by his peers, whose motivations are certainly suspect. From this distance, his guilt or innocence is immaterial, but his mistreatment is indisputable and something we need to be aware of in our own time.

You’re exactly right, Roberta: the powers-that-be wanted him out, and they succeeded. They even managed, years later, to subdue any protestations on Onderdonk’s behalf. Very sad story!

Hello,

Not sure you will ever see this. I am descended directly from Hendrik Onderdonk, and only recently confirmed the link with the old merchant’s house, for which I have written supportive letters at various times in the past. The ‘naughty bishop” was brother to my ancestor.

I bought a set of handwoven dishtowels in India to donate to your gift shop. Now wondering if you still have a gift shop! I would be glad to send them on. Back in the house’s day, most such things were woven in India, and I felt they would be appropriate. My field is Indian performing arts.

I think the bishop is not actually buried in that sarcophagus, but up in the Bronx. I have photos I took about 20 years ago of the family gravestones, as well as the church. I have worked sporadically on family history, but just turned 80 and am running out of gas! Thank you for your work on getting the story together. Katherine 12/02/2024

Hello Katherine!

Thank you so much for your comments! It’s wonderful to “meet” an Onderdonk descendant.

I did learn that Bishop Onderdonk is buried at Trinity Church’s cemetery in Upper Manhattan, not in the downtown church where his monument lies. I will change the information in the post to reflect that.

Our shop is still going strong. How kind of you to purchase the dishtowels. We would be happy to accept them to sell in the shop.

Happy Holidays!