The Irish Servants

What little we know about the Tredwells’ servants comes from census reports. We know four women were usually in residence, they came mostly from Ireland, and a complete turnover occurred at least every ten years. But they themselves left no written record. On the 1855 New York State census, we see their actual names: Ann Clark, Bridget Murphy, Mary James, and Mary Smith. Mary Smith was only 14 when she emigrated to New York in 1851; Bridget Murphy, just 16 when she arrived in 1852.

These “Irish girls,” as they were typically called, no matter what their age, worked very long hours with little pay. Usually households like the Tredwells’ had a cook, who was also responsible for the laundry, and her helper, who also waited on the tables; as well as a parlor maid and a “second girl,” who tended to the upkeep of the parlor floor and the bedrooms.

Servants’ Fourth Floor Bedroom |

. . . . . . . . . |

“Arguably the oldest intact site

|

The Servants’ Work

The work of the servants was physically demanding, and their hours were long. They were on call 24 hours a day. They were expected to rise before dawn and their work was not finished until after dark, with only one afternoon off per week. Every day the servants climbed flights of stairs over and over carrying heavy buckets of coal upstairs and ashes downstairs; clean water up, dirty water down; clean clothes and linens up, dirty clothes and linens down. The servants washed and ironed and cleaned and cooked and dusted and scrubbed on their hands and knees. And only at day’s end could they sew and mend their own clothes.

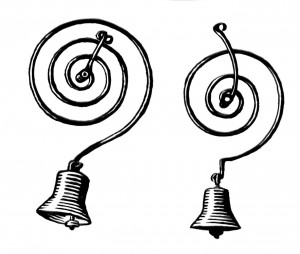

Servant Call Bells, Illustration by Robert Van Nutt

Poverty, Prejudice, and Perseverance

Servants’ wages were meager: between three and four dollars a month. However, one can understand why an Irish immigrant would prefer domestic service to better-paid factory work. She didn’t need to worry about buying food or fuel for heat, and most employers provided medical care (such as it was). At night she was safe in her attic room where she was not exposed to disease as she would have been in a teeming, fetid tenement. Here, she shared her room with only one other servant, who had the same religious beliefs and memories of Ireland.

Society subjected the Irish immigrants to cruel prejudice, casting them as ignorant, fond of drink, stubborn, and dirty. But the “Irish girls” were strong and, with training, learned to do what was expected of them. Most of all, they were available. Young American women considered domestic service demeaning, and because it came to be thought of as typical Irish work, it bore even more of a stigma.

In spite of prejudice and a life of extreme hardship, Irish immigrants, mostly single women, sent a millions of dollars home to Ireland to enable their sisters and cousins to emigrate. The “Americkay letter” containing money or tickets was anxiously anticipated in Irish villages. Steerage fare was $20. This plus $5 for expenses was what it cost to “bring out” a relative.

Some Irish servants eventually married; some left service for the needle trades; a few returned to Ireland; and some grew old in service and became dependent on Catholic charities for their sustenance. While we know very little about the Irish servants individually, one thing is certain: it would have been impossible to run a 19th century urban home like this one without them.