“This Fine Old Custom:” New Year’s Day “Calling” in Old New York

by Ann Haddad

The holidays often elicit memories of Christmases and New Year’s gone by, and of the family and friends who shared those joyful days. Let us venture beyond our own past for a moment and imagine a New Year’s Day at the Tredwell home on Fourth Street in the mid-19th century; for no doubt this New York family was celebrating what was considered to be the most important and festive day of the entire year.

A Day of Calling as Social Atonement

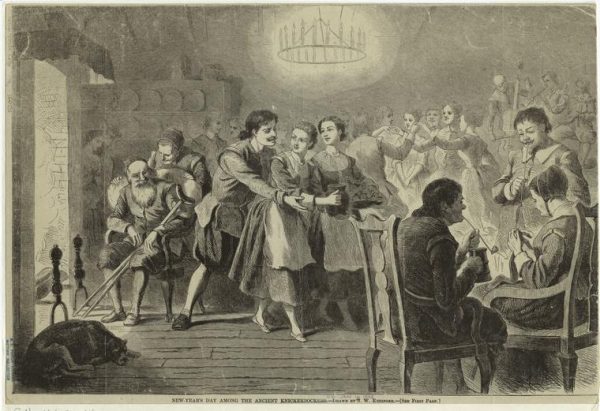

“New York without New Year’s would be like Rome without Christmas.” So wrote Matthew Hale Smith in his Sunshine and Shadow in New York (1879) of the unique custom of paying social calls on New Year’s Day. Dating to the arrival of the Dutch in New Amsterdam, this “day of social atonement,” served to redeem social sinners who had neglected family ties and friendships; visiting all the households within one’s circle was a way of renewing and strengthening old bonds. While the ladies remained at home to receive guests (indeed, no genteel woman would be seen on the streets on New Year’s Day), gentlemen ventured to the homes of esteemed women of their acquaintance, to pay their respects and offer good wishes for the New Year.

1789: His Excellency Approves

George Washington was introduced to this New Year’s Day custom in 1789, when, as newly elected President, he received calls from the elite gentlemen of New York society at his residence on Cherry Street. Upon being told that it was a tradition handed down by the Dutch forefathers, Washington remarked,

“The highly favored situation of your city will, in process of time, attract numerous emigrants, who will gradually change its ancient manners and customs, but never give up the cheerful, friendly observance of New Year’s Day.”

Drawing on the Family Purse

To provide a dose of the generous hospitality for which New Yorkers were known, and to be ready for the onslaught of guests that would arrive on New Year’s Day, the entire Tredwell household was thrown into a frenzy of costly and elaborate preparations for several weeks in advance. The four servants were charged with cleaning the house from top to bottom; families sometimes went so far as to purchase new furniture, carpets, and curtains for the occasion.

As the matron of the house, Mrs. Tredwell oversaw the preparations of her New Year’s Day buffet; it must be elegant and luxurious, set with her finest china and silver, and ample enough to feed at least 100 callers. No doubt all the Tredwell women, as well as their four servants, rolled up their sleeves for the marathon baking, roasting, and brewing that was required. The lavish menu might include boned turkey; chicken salad; sandwiches; jellied tongue; pickled oysters; iced plum cakes and pound cakes; and macaroons, Dutch crullers, and other sweetmeats. The spread invariably included alcohol: wine, Madeira, or a festive whiskey punch. One popular brew, “Perfect Love,” was a whiskey, honey, and water concoction the origins of which can be traced back to early 17th century New England.

| . . . . |

.

The Buffet

As the New Year’s Day calling ritual grew in popularity, New York City merchants were quick to seize the opportunity for profit by offering extravagant options for the buffet. Many city bakers sold special oversized “New Year’s Cakes,” and often made them available for viewing prior to the holiday, for a price. The following advertisement was noted in The Evening Post on December 22, 1838:

“The largest plum cake ever exhibited in America can be seen at Amelie’s Saloon, no. 395 Broadway. It is an immense mass of the richest materials, weighing over three thousands pounds, and is 18 inches larger in diameter than the cake of last year. It is deservedly called the “Ne Plus Ultra.” An elegant Grecian Temple, ornamented with exquisite taste, contains this luscious Monster. Admission to the cake 12 1/2 cents. The above cake will be cut on Monday next for New Year’s Day.”

As coffee was considered a necessary beverage at the buffet (perhaps as an antidote to all the alcohol consumed), newspaper advertisements for coffee urns were plentiful in December. One creative merchant, Boardman and Hart, on Burling Slip, offered the following ditty as an enticement to shoppers in 1837:

“And while the bubbling loud and hissing Urn

Throws up a steamy column, and the cup

That cheers, but not inebriated, waits on each

So let us welcome cheerful New Year in.”

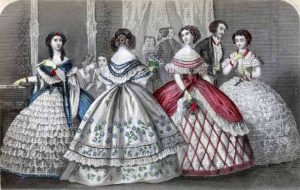

Bedecked and Bejeweled

Equally as important as the buffet to the fashionable New York women of means was their attire. Magnificent new dresses were commissioned from the dressmaker, and new or cherished jewels proudly worn. Hairdressers were in high demand, and often arrived at the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve to work their magic:

“From twelve o’clock midnight till twelve o’clock noon, New Year’s, the lady with the ornamented head-top maintains her upright position, like a sleepy traveler in a railroad car, because lying down under such circumstances is out of the question.”

One can only imagine the scene of mayhem in the Tredwell household on New Year’s Day morning, with the cooks toiling in the kitchen, the two other servants assisting the six daughters with their toilettes, and

Mrs. Tredwell running up and down stairs supervising it all!

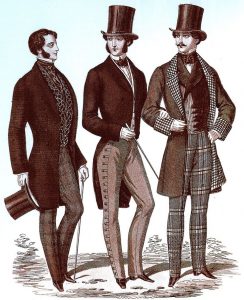

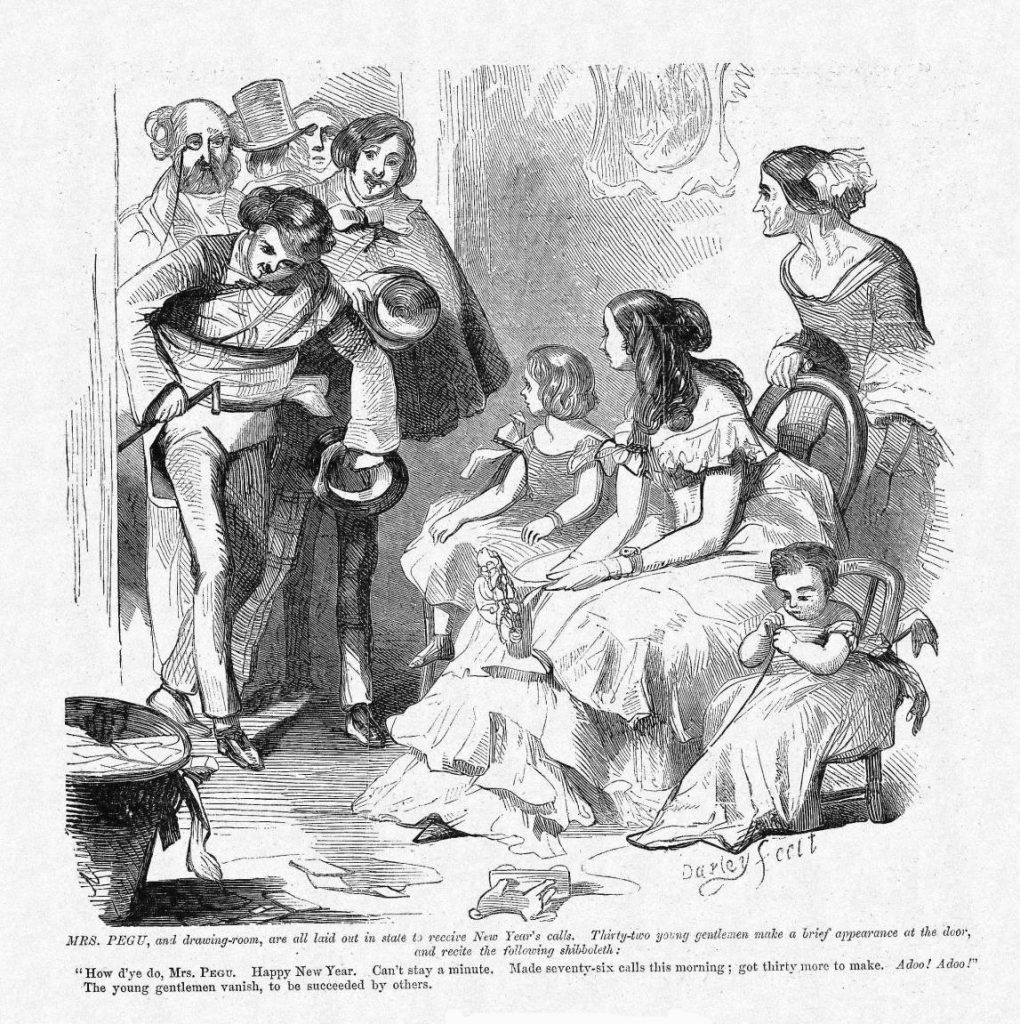

Calling as a Military Campaign

| . . . . |

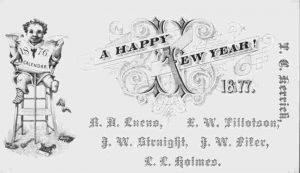

Gentlemen (with the exception of the newly-married, who would remain behind with their wives to receive), made their calls between 10 a.m. and 10 p.m. They carried their list of addresses, and a full supply of calling cards, which conformed to a certain standard:

“A gentleman’s visiting card should be small, plain, ungilt, and unglazed. Have your name engraved distinctly in neat characters. Never have your card printed.”

Seabury Tredwell, who perhaps made calls with his sons Horace and Samuel Lenox, no doubt considered a pair of comfortable shoes to be a necessity if he was to travel on foot to all the homes on his list. In 1866, John Ward, who lived near the Tredwells, related his New Year’s Day travels in his diary:

.

“Called at 107 houses, leaving cards at 36 of them, and finding 71 at home. Started at Washington Square, thence to Bond St, up 2nd to 17th, to Union Square, down the east side to 10th St, up the West Side to 21st, then back and forth, east and west of Fifth Avenue until we reached 47th Street.”

In a satirical piece published in the Long Island Star in January 1845, one energetic young man related to a friend how he managed to make 184 calls between 10 a.m. and 10 p.m.:

“Twelve hours multiplied by 60, shew (sic) 720 minutes — 720 minutes divided by 4, shew 180 visits, four minutes to a visit; and so I went by calculation.”

Another young New Yorker, Richard Stoddard, likened his New Year’s Day calling adventure to a military campaign:

“So the campaign opened, and so the engagement went on … Recruits of eighteen and twenty may have blundered somewhat in their drill before the Day was over, but old soldiers of twenty-four pressed on unflinchingly until nightfall. We were brave, we were young, we were light-hearted, and if we had a little headache in the morning we didn’t mind it much.”

On New Year’s Day, 1844, diarist Philip Hone (1780-1851), former New York City Mayor, merchant, and philanthropist, set out from his home on Broadway and Great Jones Street (one block from the Tredwells):

“I was out more than five hours, and my girls tell me they received one hundred and sixty-nine visits. This fine old custom, almost peculiar to New York, does not lose favor in the eyes of our citizens.”

In the event of bad weather, and as the city boundaries extended, gentlemen might opt to hire a pair of horses from a livery stable to make their rounds, or hire a carriage driver, who would of course raise his prices, charging up to $50 for the day’s service. The city presented a general spectacle, as Matthew Hale Smith noted in 1879:

“With its sidewalks crowded with finely-dressed men, its streets thronged with the gayest and most sumptuous equipages the city can boast, the whole looks like a carnival.”

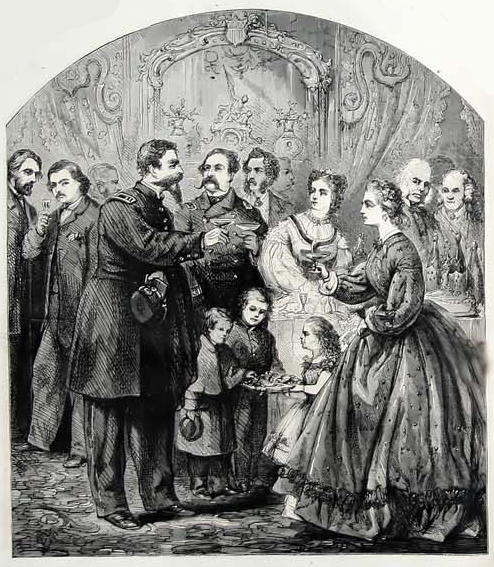

The Ladies Were “Monstrously Dignified”

Upon arrival at the Tredwell house, a gentleman presented his card to a servant bearing a silver tray; he was then escorted into the formal Greek Revival double parlor. (He would not be invited to remove his coat.) There he was greeted with a curtsy by the ladies of the house, and he bowed in return. Mrs. Tredwell, as hostess, invited him to partake of the buffet, and he politely nibbled on an oyster or a piece of cake, and enjoyed a cup of punch. Then conversation would ensue; approved topics included the weather, compliments on the finery of the women, and the elaborateness of the buffet. After about five minutes, the gentleman was off to his next call. Social etiquette prohibited any variation from this protocol. In 1842, young Theodore Cuyler wrote to his aunt of the Misses Chauncey he had met:

“Oh! what Paragons! worth about $150,000 apiece – tall – handsome – intellectual – good tempered – and so monstrously dignified that the slightest faux pas in etiquette would throw them into convulsions.”

No doubt a certain amount of flirting (out of earshot of the ladies’ mother) took place between the young single ladies and gentlemen. In 1861, John Ward wrote:

“I complimented Miss Julia [Carville] on her personal appearance and she replied that I was at my old ways again and wished she could hear what I said to the next lady if she could be behind a door!”

Too Much of a Good Thing

As the population surged and social circles widened, the number of calls made by elite gentlemen increased, and the effects of over-consumption of alcohol became more apparent. (The pro-Temperance set had warned against serving “the deadly poison” on New Year’s Day for years.) Etiquette was ignored, artifice replaced honest sentiment, and women were shocked and embarrassed by the men’s behavior. In her novel, Rose in Bloom (1876), Louisa May Alcott depicts the heartbreaking disappointment endured by her heroine, Rose, when her beloved cousin Charlie breaks his promise and returns to her inebriated after a day of New Year’s calls:

“O Charlie! How could you do it! How could you when you promised?”

| . . . . |

Another practice that horrified society women on New Year’s Day as the century wore on was the increasingly prevalent calling on the part of utter strangers. Young men who worked together amassed in large groups to descend on the homes of their unsuspecting employers. In 1867, the New York Daily Herald reported that the wild parties:

“… swept through he streets, clearing the tables of everything edible, evaporating all the liquors, smoking all the cigars. One of these parties, numbering a full forty men – called the “Dead Beat Club,” called at several aristocratic mansions, and to the horror of the ladies who did the honors, fairly cleared the table before the day was half spent.”

By the 1880s, many women chose to retreat behind closed doors and instead placed baskets on their door knobs for the gentlemen’s cards.

An “Antiquated” Knickerbocker Custom

| . . . . |

As New York City extended its boundaries further north and the population boomed, it became impossible to maintain the intimacy of the New Year’s Day custom. By 1891, the New York Times called the tradition “antiquated,” ultimately giving way to the celebration of New Year’s Eve. Dinner parties, either at home or in restaurants, became de rigueur for New Year’s Day celebrations. The wealthy members of the upper class often escaped to their country homes for the holiday, only to return after the first of the year for the “winter season.” Edith Wharton references the demise of the custom among the social elite in her novella, New Year’s Day:

“… Mrs. Henry van der Leyden had clung to it … long after her friends had closed their doors on the first of January, and the date had been chosen for those out-of-town parties which are so often used as a pretext for absence when the unfashionable are celebrating their rites.”

In 1894, New Yorker Edgar Fawcett wrote:

“Christmas yet reigns, but her sister holiday is annulled and forgotten. And among the few mourners that survive her I confess myself one of the sincerest.”

Perhaps we should recall the words of New York poet James Nack (1809-1879), who in 1852 wrote a poem for his daughter Evelina, A New Year’s Greeting to My Daughter, which begins:

“So it is gone! another year!

A drop of time lost in the sea

Of dark and deep eternity,

In which we all must disappear!

Well, since so transient our career,

The blessings that attend our way

May precious grow with every day!”

At the Merchant’s House Museum, we continue the 19th century tradition of renewing, reviving, and reaffirming friendships on New Year’s Day. Please join us on Monday, January 1, from 2 to 5 p.m. for tours of the house, 19th century readings about New Year’s Day celebrations, and punch and confectionery.

Happy New Year!

Sources:

- Alcott, Louisa May. Rose in Bloom. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1876.

- An American Gentleman. True Politeness. A Handbook of Etiquette for Gentlemen. New York: Leavitt and Allen, 1848. NYHS BJ 1855. T9.

- Fawcett, Edgar. “New Year’s Day in Old New York.” Lippincott Monthly Magazine, Volume 55, 1894, p. 138. babel.hathitrust.org. accessed 12/5/17.

- Knapp, Mary. An Old Merchant’s House. Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- Lyman, Susan E.. “New Year’s Day in 1861.” New York Historical Society Quarterly, January, 1944, p. 21-28:

- Morrell Family Papers, Box 1. Manuscripts Division. New-York Historical Society.

- Nack, Evelina. BV Autograph Album. Manuscripts Division. New-York Historical Society 1852-53.

- Nevins, Allan and Milton Halsey Thomas, eds. The Diary Of George Templeton Strong. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1988.

- The Evening Post, 27 Dec 1815, Wed, Page 2. newspapers.com, accessed 11/29/17.

- The Evening Post, 22 Dec 1838, Sat, Page 2. newspapers.com, accessed 11/29/17.

- The Long Island Star, 08 Jan 1835, Thu, Page 2. newspapers.com, accessed 11/29/17.

- New York Daily Herald, 2 Jan 1867, Wed, Page 6. newspapers.com. accessed 12/5/17.

- New York Tribune, 26 Dec, 1843, Tues, Page 1. newspapers.com. accessed 11/29/17.

- Pintard Papers, Box 7, Folder 8. Manuscripts Division. New-York Historical Society.

- Smith, Matthew Hale. Sunshine and Shadow in New York. Hartford, CT: J.B. Burr and Co., 1879. internetarchive.org. accessed 12/5/17.

- Stoddard, Richard Henry. New Year’s Day Half a Century Ago. New York: Bacheller, Johnson & Bacheller. [1896] New-York Historical Society. Pamph GT 4905.S76 1896.

- Tuckermam, Bayard. The Diary Of Philip Hone, 1828-1851, Volume 1and 2. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1889.

- Wharton, Edith. “New Year’s Day,” in Old New York. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1924.

- Yates, Donald. “Beginning Tavern History,” Bottles and Extras, May-June, 2007, p. 38. www.fohbc.org. accessed 12/4/17.