Vauxhall Garden: The Coney Island of Its Day

by Ann Haddad

From the early 18th century, pleasure gardens – outdoor complexes that offered landscaped vistas, various entertainments, and refreshments – were popular escapes for New Yorkers starved for open space in the rapidly expanding city. Central Park was not established until 1857.

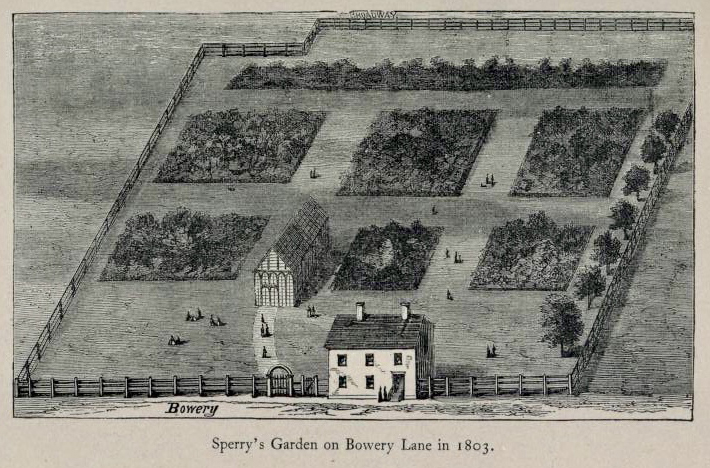

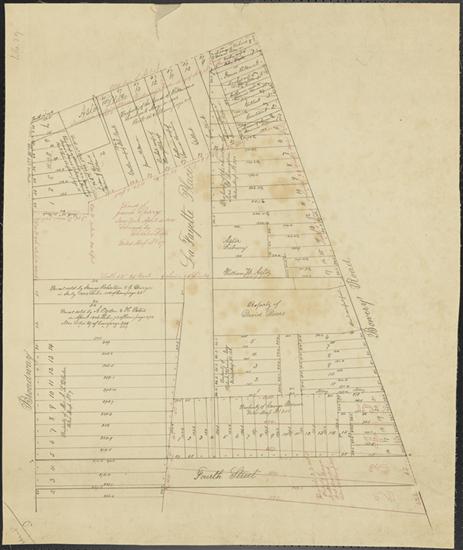

In 1835, when the Tredwell family moved to fashionable Fourth Street (well within the boundaries of the elite “Bond Street area”), the neighborhood was in the midst of significant development. One enormous change was the transformation of the pleasure garden know as Vauxhall Garden into residential and commercial properties. The Garden, which abutted the Tredwells’ rear garden wall, originally occupied a three acre area bounded on the south by Fourth Street, on the north by Art Street (now Astor Place), west by Broadway, and east by the Bowery Road (now 4th Avenue). It was the third and final iteration of Vauxhall Garden. But the land that became Vauxhall Garden had been well known, in the mid-to-late 18th century, as the site of Sperry’s botanical garden.

A Botanical Garden

| .. |

..

Jacob Sperry was a young man of 20 when he arrived in New York City from Zurich, Switzerland, in 1748. Although trained as a physician, his passion was horticulture; in 1771 he turned a plot of pastureland into a garden that, despite its two-mile distance from the city proper, became the go-to florist shop of its day. So famous had the spot become, wrote the New York Daily Herald in 1855, that:

“Thousands, who now live, remember the time when Sperry’s garden was the great resort of belles and beaux for the purchase of their bouquets.”

..

..

Imagine Seabury Tredwell as a young single gentleman, riding up to Sperry’s to purchase a posey for a young lady!

Sperry cultivated the land until 1803, when he sold the property to John Jacob Astor for $45,000. Astor, who had turned his attention from the fur trade that brought him great wealth to the acquisition of real estate, undoubtedly realized that the property’s value would only increase as the city’s population migrated further and further uptown.

The Three Vauxhall Gardens

Once it became a British colony in 1674, New York adopted the customs and manners of the mother country; tea-drinking became extremely popular. To quench the public’s thirst for this beverage, Samuel Fraunces (popularly known as the owner of the tavern that still bears his name), opened the first Vauxhall Garden, named after London’s famous Vauxhall, in 1767. Along with tea, it served other beverages, hot rolls, and the new “ice cream” dessert. Situated on a hill near Greenwich Street between what is now Warren and Chambers Streets, it afforded sweeping views of the North (Hudson) River. In addition to admiring the flowering shrubs and trees, guests strolled through the wax museum, and were awed by the fireworks displays. After the Revolutionary War, Fraunces sold the property and the site became a pottery.

The second Vauxhall Garden, located near present-day Grand and Mulberry Streets, was established in 1798 by Joseph Delacroix, a Frenchman who had previous careers as a distiller and confectioner. He operated the garden until 1803; upon learning that Sperry’s former garden was for rent, he immediately obtained a 21-year lease from its owner, John Jacob Astor. It was here that Delacroix achieved fame and fortune, for the third and final Vauxhall Garden became one of the most popular and fashionable attractions in the city.

A Place for Romance

In laying out his new garden, Delacroix wisely retained Sperry’s lovely flowers, trees, and shrubs; he added meandering gravel paths; fountains; strings of hanging lamps configured as stars, serpents, and moons; and statuary, including a central equestrian figure of George Washington. The orchestra was situated amidst the trees, which, according to The Picture of New York (1807):

“… gives to the band of music and singing voices, a charming effect on summer evenings.”

The garden was surrounded by a high board fence, with entrances on Broadway and Bowery Road. Alcoves for seating were discreetly arranged along the inner perimeter of the garden fence; they provided areas of elegant seclusion, and afforded many a young gentleman the privacy required for courtship. According to the New York Daily Herald in 1855:

“How many couples that still live remember Vauxhall Garden as the place where their first vows were made!”

Drinks and Theatre

Sperry’s former greenhouse was converted into a saloon, offering desserts such as “Delacroix cream” (ice cream), as well as alcoholic beverages. Delacroix was known for the cordials and brandy made in his distillery, in flavors such as anisette, cinnamon, cherry, and one with the intriguing name “Matrimony.” He later bottled and sold a “Vauxhall Beverage,” a concoction of herbs and milk, which was guaranteed made fresh every morning, and which caused one teetotaler to write in 1820:

“Our drinkers would be much more benefited by your fresh and mild beverage, than by the strong liquors unfortunately much in fashion.”

| .. |

A small theatre in the Garden offered dramatic tableaux; these proved to be exceedingly popular, due in part to the fact that the downtown Park Theatre (on Park Row near City Hall), was closed during the summer months. Martha Lamb, in A Neglected Corner of the Metropolis (1886), claims that in the summer of 1809, David Poe, Jr., and Elizabeth Arnold Poe, the parents of Edgar Allan Poe, made their first appearances in a New York theatre at Vauxhall in Fortune’s Frolic:

“‘She was young and pretty,’ the critics said, ‘and evinced talent both as a singer and an actress; but Poe was literally nothing.’”

Vauxhall Garden’s season ran from May through September. To keep out those who were “not genteel in character,” and to avoid use of the Garden simply as a place to promenade, Delacroix charged an admission fee of 2 shillings per person, which entitled the visitor to “one glass of any refreshment.” For his patrons’ convenience, and for a small fee, he engaged a special coach to make round trips from the City Hotel, located on Broadway and Cedar Street, to the Garden.

..

“As Gay a Place”

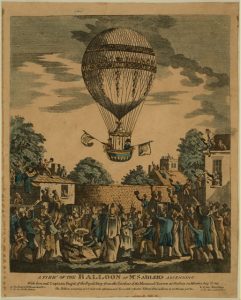

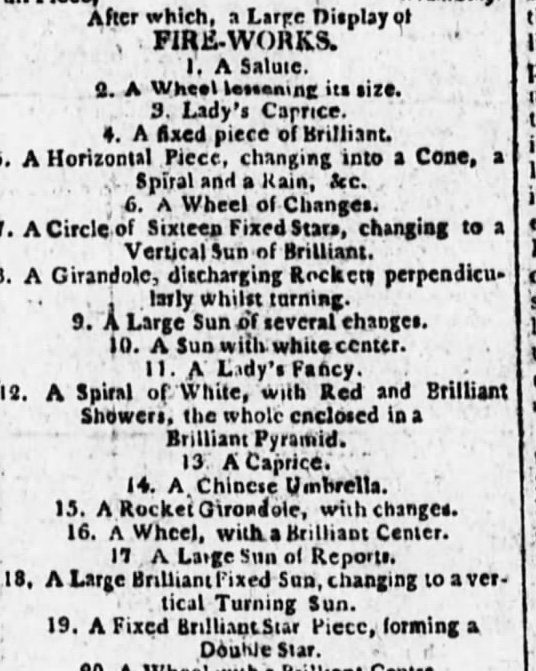

As early as 1806, huge crowds were drawn to Vauxhall Garden to see the popular balloon ascensions, and numbered nearly 20,000 for special events, especially for the elaborate Fourth of July fireworks spectacular. Delacroix’s advertisement in the Evening Post, June 24, 1805, gave a preview of the grand display that was to come.

Delacroix enjoyed 16 years of unparalleled success as owner of Vauxhall Garden. No doubt he would not be surprised to read the following, written nearly 100 years after his retirement in 1819:

“All the town flocked to it. It was to the New York of that day something like what Coney island is to the New York of today. The people of New York considered it to be about as gay a place of recreation as could be found anywhere.”

Cut through the Heart: Lafayette Place Opens

The slow decline of Vauxhall Garden began after 1820; Delacroix’s son, Clement, who succeeded as owner, simply did not have the name cachet to attract the public.The greatest blow came in 1826, however, when John Jacob Astor opened broad Lafayette Place, which extended from Great Jones Street to Astor Place, and cut right through the heart of the establishment. The new street ran parallel to Broadway and the Bowery Road, thus reducing the Garden to half its original size. Joining coveted properties on Bleecker, Bond, and Great Jones Streets, Lafayette Place became a fashionable residential street, especially after fancy LaGrange Terrace was built in 1833.

Vauxhall Becomes Second-Class

After 1830, Vauxhall Gardens went through a series of managers, each of whom struggled unsuccessfully to restore its former glory. The entertainment was reduced to minstrel shows, low-budget concerts, and so-called “calico balls” (no society woman would be caught dead in calico). At various times it was the site of livestock fairs, a riding academy, a dancing school, and a place to test fire safes. The elite were drawn to more elegant and upscale destinations, such as Niblo’s Garden, which opened in 1828 on Broadway and Prince Street. By that time the patrons of Vauxhall were largely members of the working class, and rowdiness, drunkenness, and brawls between rival street gangs were regular occurrences. Complaints of disturbances of the peace became commonplace, especially on Sundays, when the din emanating from within the Garden’s walls interfered with neighboring church services. On July 11, 1843, a passerby complained of the loud music emanating from the Garden, as well as:

“… the loud hammering of the visitors upon the tables to attract the notices of the servants, the loud calls for ice cream, &c. So loud were the strains from the band that all four congregations must have been seriously disturbed, not to speak of the neighbors who might wish to enjoy a quiet Sabbath at home.”

| .. |

..

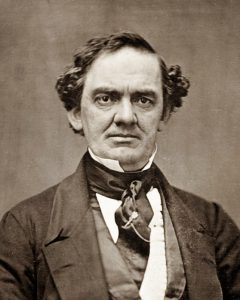

Barnum Has a Go

Even the showman and impresario Phineas (P.T.) Barnum tried his hand at resuscitating Vauxhall Garden. He leased the establishment from 1840 through 1841. His offerings included variety shows that featured low-budget, plebeian entertainment; in one instance he presented:

“Feats of Legerdemain and Necromancy [magic tricks and communicating with the deceased] by the wonderful young Sybil and Enchantress, Miss Wyman, only 14 years of age.”

But the meager profits earned after two seasons of managing Vauxhall Garden were not enough for the ambitious Barnum, who went on to more lucrative ventures.

..

..

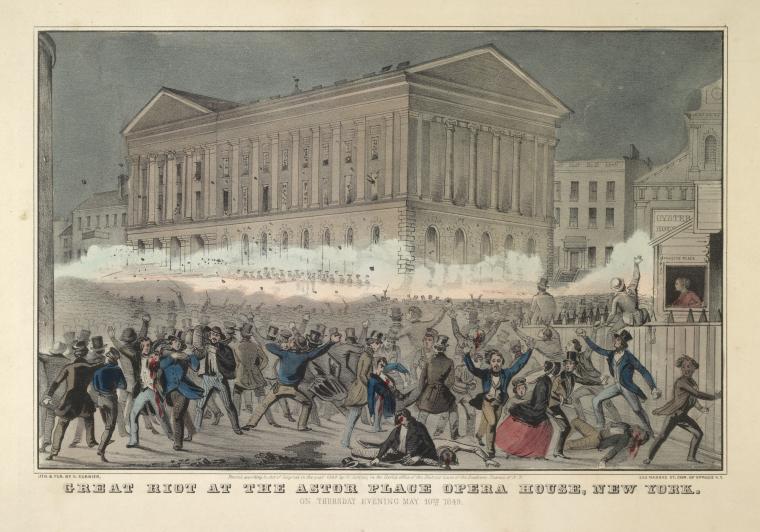

The Last Nail in the Coffin

The event that no doubt doomed the Vauxhall Garden to its eventual demise was the Astor Place Riot on May 10, 1849, which took place outside the Astor Opera House, just steps away from Vauxhall. A violent encounter sparked by the rivalry between two actors, one British and one American, but reflective of the growing class tensions in New York, the melée left 22 dead and more that 150 injured. At least one of the wounded allegedly died on a billiard table in Vauxhall Garden.

When the Astor Library (now the site of the Public Theatre) was built in 1853, Vauxhall Garden was whittled down to one eighth of its original size. The Bowery, lined with taverns, became the destination for those seeking risqué entertainment; the Garden ultimately was reduced to a shabby vaudeville and burlesque house and saloon, and became a popular site for political meetings. It closed in 1859, a victim of commercial ventures and the urbanization of New York City.

It is doubtful that the Tredwell family would have frequented Vauxhall Garden; its attractions were losing popularity among the elite by the time the family arrived at Fourth Street in 1835. They need only step into their back yard to hear the music, see the fireworks — and in the Garden’s waning years, be disturbed by the rowdiness of its clientele.

Sources

- Bayles, William H. Old Taverns of New York. New York: Frank Allaben Genealogical Company, 1915. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/9/18.

- Bristed, Charles Astor. The Upper Ten Thousand: Sketches of American Society. London: John W. Parker and Son, 1852. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 1/5/18.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: a History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Dayton, Abram Child. Last Days of Knickerbocker Life in New York. New York: Charles W. Dayton, 1880. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/5/18.

- DeVillo, Stephen Paul. The Bowery: The Strange History of New York’s Oldest Street. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2017.

- Eaton, Walter Prichard. “Lafayette Place.” In Brown, Henry Collins, ed., Valentine’s Manual of Old New York, New Series, Number 2, 1917-18. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/4/18.

- The Evening Post, Tuesday, May 10, 1803, p. 4. newspapers.com. Accessed 1/5/18.

- The Evening Post, Monday, June 24, 1805, p. 2. newspapers.com. Accessed 1/5/18.

- The Evening Post, Tuesday, August 19, 1806, p. 3. newspapers.com. Accessed 1/9/18.

- The Evening Post, Friday, January 5, 1810, p. 4. newspapers.com. Accessed 1/5/18.

- The Evening Post, Monday, June 5, 1820, p. 2. newspapers.com. Accessed 1/5/18.

- The Evening Post, Thursday, June 25th, 1840, p. 3. newspapers.com. Accessed 1/6/18.

- Hemstreet, Charles. Nooks and Corners of Old New York. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1899. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/6/18.

- Kaplan, Justin. When the Astors Owned New York. New York: Penguin Group, 2006.

- Lamb, Martha J. “A Neglected Corner of the Metropolis,” Magazine of American History, Vol. XVI, No. 1, July, 1886. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 1/2/18.

- Lockwood, Charles. Manhattan Moves Uptown. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1976.

- McCabe, James D. Lights and Shadows of New York Life; or, the Sights and Sensations of the Great City. Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, 1872. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/2/18.

- Mitchill, Samuel L. The Picture of New-York, or, The traveler’s guide, through the commercial metropolis of the United States. New York: I. Riley & Co., 1807. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/4/18.

- New York Daily Herald, Saturday, March 24, 1855, p. 1. newspapers.com. Accessed 1/9/18.

- New-York Tribune, Tuesday, July 11, 1843, p. 2. newspapers.com. Accessed 1/6/18.

- The Sun, Wednesday, October 12, 1859, p. 3. newspapers.com. Accessed 1/7/18.

- Ukers, William Harrison. All about Tea, Volume 1. New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, 1935.

Nature for Ladies: The Victorian Art of Flower & Seaweed Pressing

by Ann Haddad

Escaping the Summer Heat

As city dwellers do today, many 19th century New Yorkers desired to escape the wretched summer heat and humidity by retreating to the seaside or country for the fresh air and cooler temperatures. For the Tredwells, that usually meant traveling to Rumson, New Jersey, where they relaxed at their 850-acre farm near the ocean. But the summer of 1865 must have been a difficult time for the family. Their grief over the loss of Seabury Tredwell in March surely was still fresh, and they were only four months into their one-year mourning period.

A Change of Scenery

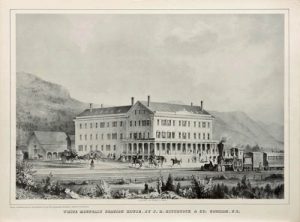

Perhaps that is why, in July 1865, 24-year-old Gertrude, no doubt along with other family members, chose a new destination. Instead of, or in addition to, summering in Rumson, they ventured to both the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and Northampton, Massachusetts. Popular tourist attractions in the mid-to-late 19th century, the White Mountains in particular drew many celebrated visitors, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, painter Thomas Cole, and Mary Todd Lincoln who, along with her son Robert, journeyed there in 1863. Northampton was called the “loveliest village of America” by The New York Times in 1865.

A Long Journey

Gertrude and her entourage could have taken two routes to reach the White Mountains. One was to hire a carriage to bring them to Peck Slip on the East River in lower Manhattan. There they would board the 3:15 p.m. steamer and travel to New Haven, Connecticut, then switch to the New Haven Railroad and later, a stagecoach, which would bring them to the White Mountains. Or, the carriage driver may have been directed to the New Haven Railroad depot at Fourth Avenue and 27th Street, where the group would board the 12:15 p.m. train and travel exclusively by rail. Either way, the day-long journey necessitated an overnight lodging, usually in Springfield, Massachusetts.

After spending a week or two enjoying the beauty of nature in the White Mountains, Gertrude and her fellow travelers made the return trip by rail, stopping for a time in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she and her party ascended Mt. Holyoke. Here she enjoyed another idyllic mountain scene, and the quiet beauty of the Connecticut River Valley, before returning home.

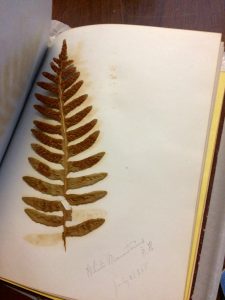

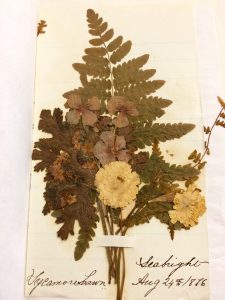

A Bounty in the Archives

How do we know for certain that Gertrude visited the White Mountains and Northampton in July 1865? The Tredwell Archives at the Merchant’s House Museum contain a large collection of pressed flowers and seaweed, both mounted in scrapbooks and on loose leaves, dating from 1858 to 1876. The scrapbooks bear Gertrude’s name and she made notations on several of the pages indicating where the specimens were obtained, such as “Mt. Holyoke,” “Northampton,” and “White Mountains.” They were dated either July 1865, or July 20, 1865.

- (Click images to enlarge.)

Mother-Daughter Time

We are not certain if all of the pressings in the extraordinary collection were made by Gertrude. Her sisters may also have enjoyed the hobby. But we do know that both scrapbooks of pressed flowers, ferns, and seaweed bear her name; and many individual pages bear the initials “E.T,” and “E.E.T.” This can only be Gertrude’s mother, Eliza Earle Tredwell. Perhaps Gertrude developed her obvious passion for the craft from her mother; it may have been an activity they pursued and delighted in together.

A Victorian Pastime

In the mid-19th century, flower pressing emerged as one of the most popular pastimes for Victorian middle and upper class women. With plenty of time on their hands, and no dearth of resources, they sought to explore their artistic side in unique ways. Wishing to be part of the skyrocketing craze for natural history at that time, yet restricted by virtue of their sex, many women found the art of identifying and collecting plant specimens to be a respectable way of examining the natural world, improving their scientific knowledge, and preserving the beauty around them. It became an acceptable way for women to merge the natural world with the domestic one; respect for nature was also viewed as a Christian road to God. A woman given to this pastime would pride herself on her “herbarium,” or collection of flora.

Women also pressed flowers for sentimental and romantic reasons. The flora pressed into a book or album served as a remembrance of a particular person or event; for Gertrude, her scrapbook also served in part as a travel log.

.

.

A Kindred Spirit

One well-known herbarium maker was the poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), who as a young girl pressed many specimens into a bound album, much like the ones created by Gertrude. In an 1845 letter to a friend, Emily wrote, “Have you made an herbarium yet? I hope you will if you have not, it would be such a treasure to you; most all the girls are making one.”

It is pleasant to imagine Gertrude and Emily (who lived only 10 miles away in Amherst) meeting on Mt. Holyoke as they pursued their shared passion!

How It Was Done

In order to maintain the freshness and vibrant color of the florals, Gertrude or Eliza purchased a wooden field press. Many stationers quickly caught on to the popularity of the hobby and rushed to stock presses and other needed supplies, such as paper and glue. For those who desired to learn the craft, popular magazines often published instructions, especially in the fall when the brilliant colors of the autumn foliage would inspire collecting.

Picking the flowers late in the afternoon ensured that all the dew had dried. They were then placed between sheets of blotting paper and pressed with a crank or straps to tighten and flatten the specimen. Once dried, the flowers were glued, sewn, or attached onto paper (which was plentiful and inexpensive during the Industrial Revolution), silk, velvet, or other fabric. Gertrude kept hers in a scrapbook; framing under glass was also a popular way to exhibit one’s work. Or the flowers could be pressed between the pages of a beloved book or family Bible.

Many of the specimens in the Merchant’s House Museum collection are of delicate, intricately-patterned seaweed, probably gathered at the shore in New Jersey. Readily available, especially for women who spent summers at the seaside, seaweed emits a sticky, gelatinous substance when pressed, thereby eliminating the need for glue when mounting. The pungent smell subsided once the specimen was pressed. Seaweed presented an artistic and technical challenge (even for devotees such as Queen Victoria), for one had to work very carefully to avoid disrupting its complex structure. Added to that was the difficulty of wading into the water wearing heavy Victorian garb. The noted seaweed collector Margaret Gatty (1809-1873) recommended that “seaweeders” wear heavy men’s boots when wading: “Feel all the luxury of not having to be afraid of your boots.”

The collection also includes ferns gathered along the banks of the Shrewsbury River near to the family farm, as well as several specimens marked “Harlem,” reflecting the rural nature of that part of New York City in the mid-19th century.

Patience, Patience

One has to only glance at the Tredwells’ collection of pressed flora to realize the extraordinary precision, patience, and technical skill that was required to arrange the delicate specimens, especially the seaweed. Indeed, in a New York Times article from 1874, the reader is cautioned that seaweed pressing requires:

“… the greatest delicacy of touch and the most absolute attention. It would not be a bad idea to serve a preliminary apprenticeship at lace-making.”

Although they did not label their specimens, both Gertrude and Eliza created unique arrangements that are works of art. It must have taken hours to do such painstaking work; clearly both women loved exercising their artistic talents in this manner. Many of the flowers still retain their bright colors because they have had little exposure to light.

Mementos

It is uncertain if the trip to the White Mountains in July 1865 was the family’s first; they did make subsequent trips to the area, but none of the other pressings are marked as having been collected there. The latest specimen that bears Eliza’s name is dated August 24, 1876, and was collected from Seabright (another name for Rumson), when she was 79 years old! Eliza would die 6 years later, in 1882. We do not know how long Gertrude continued to enjoy the craft of flower pressing, or whether she derived joy from looking through the albums in later years. We like to think that they evoked sweet memories of happy days, and of her mother.

Sources:

- Farr, Judith. “Victorian Treasure: Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium.” February 19, 2014. Academy of American Poets. www.poets.org. (accessed 8/8/17).

- Giaimo, Cara. “The Forgotten Victorian Craze for Collecting Seaweed.” November 14, 2016. Atlas Obscura. www.atlasobscura.com. (accessed 8/8/17).

- “From Northampton. Beauties of the Scenery.” The New York Times, 01 Sep 1865, Pg. 1.

www.newspapers.com. (accessed 8/4/17). - Oatman-Stanford, Hunter. “When Housewives were Seduced by Seaweed.” Collector’s Weekly. November 7, 2013. www.collectorsweekly.com. (accessed 8/8/17).

- “Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains.” Museum of the White Mountains Online Exhibition. Plymouth State University. www.plymouth.edu. (accessed8/4/17).

- Richards, T. Addison. Appletons’ Companion Hand-Book of Travel. New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1862.

- “Seaweed Pressing.” The New York Times, 29 May, 1874, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. (accessed 8/4/17).

- Wallace, R. Stewart. “Turnpikes, Stage Coaches and the White Mountain Express: Transportation in the White Mountains.” wwwwhitemountainhistory.org/uploads/Turnpikes_enh.pdf. (accessed 8/4/17).

- Witemeyer, Karen. “Victorian Flower Pressing,” Petticoats and Pistols. April 30th, 2011. www.petticoatsandpistols.com. (accessed 8/8/17).