“A Meritorious Establishment:” Tredwell Philanthropy, Part 3

by Ann Haddad

An Elite Education for the Tredwell Children

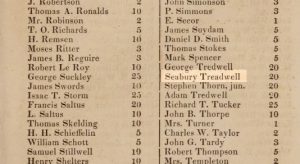

Like other affluent New Yorkers, Seabury and Eliza Tredwell chose to send their children to private day and boarding schools. Although little is known about their elder son Horace’s education, we do know that Samuel Lenox was sent to the prestigious St. Paul’s College in College Point, New York (see my blog post of September 2016). The six Tredwell daughters attended private neighborhood schools, including Mrs. Okill’s Academy on nearby Clinton Street (now 8th Street), and Miss Gibson’s School on Union Square.

The Calamity of Ignorance

Most New York City children who were fortunate enough to receive an education, however, did so at one of the many church-based charity schools, or by the nondenominational New York Free School Society (FSS), which was founded in 1805 to provide a free education to the city’s poor children whose families were not connected with any religious organization. DeWitt Clinton, then Mayor of New York City, who spearheaded the Free School Movement, said of the importance of educating the poor:

“The necessity was so pressing, the calamity of ignorance so appalling, that the problem of removing the crying shame could not be set aside or postponed.”

By 1825, aided by public funding, the FSS had educated nearly 20,000 children.

Falling Through the Cracks

Despite these successful efforts by the churches and by private philanthropy to provide children with free education, roughly 43,000 other youth, largely from indigent households, fell through the cracks. Neglected and living in poverty, they did not attend school; instead, these “loafers” and “ragamuffins” roamed the streets, often taking up lives of petty theft and vagrancy. If arrested and imprisoned, even for minor infractions, these young offenders were indiscriminately incarcerated with adults in overcrowded and rundown prisons; this disastrous combination resulted in many juveniles returning to society as hardened criminals. The conditions of the City Prison, commonly known as Bridewell, was described as follows:

“In rooms about 18 feet square, there are often thirty or forty persons, confined together, without any discrimination except that of sex and color – boys of nine years of age and upwards, sharing the same dismal fare, and mingling in conversation with aged villainy, – and girls of ten or twelve exposed to the company and example of of the most abandoned of the sex.”

The House of Refuge

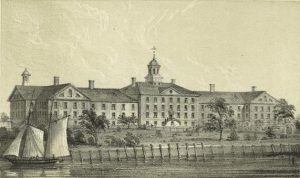

In 1824, a group of wealthy and philanthropic New Yorkers, including Cadwallader D. Colden (1769-1834), a former Mayor of New York City, recognized the need to establish a facility where young petty offenders could be segregated from adults criminals, to avoid “the contamination of youth by vicious associations.” On January 1, 1825, after raising $20,000 through private donations, the House of Refuge for Juvenile Delinquents opened its doors on Broadway (then Bloomingdale Road) and 23rd Street, in a former Federal arsenal. The first institution of its kind in America, the House of Refuge sought to rescue poor and destitute children from lives of delinquency. The outgrowth of the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism, the House of Refuge was privately managed, but supported in part by New York State and City funds.

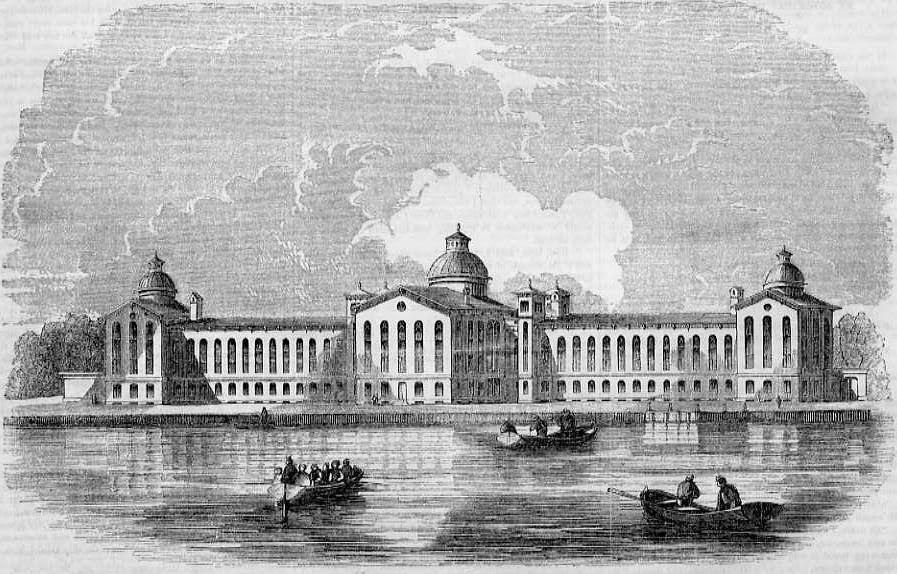

Under the supervision of Joseph Curtis, the institution opened with an enrollment of three boys and six girls. By 1832, it had outgrown its accommodations and moved to 23rd Street and the East River. It’s next and final move occurred in 1854, when it relocated to a facility on Randall’s Island that could accommodate 1,200 children.

Habits of Industry

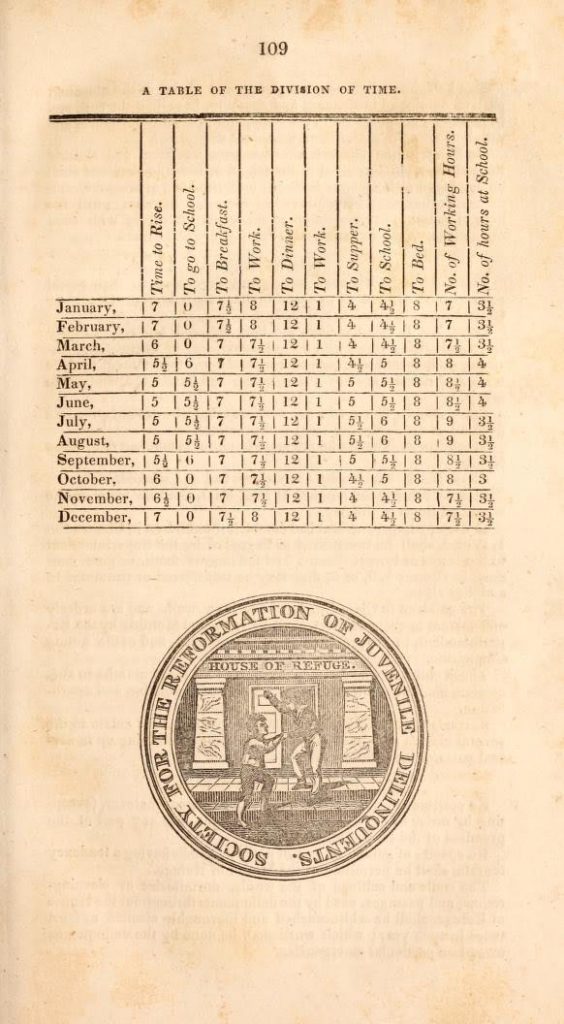

The institution accepted children under the age of 16, referred by the judicial system or their own families, who were rehabilitated through a strict daily program of school, work, and prayer. Their education, managed by five teachers, included instruction in reading, writing, arithmetic, and geography, with occasional music lessons. Religious instruction on the Sabbath was provided by the Chaplain and the Head Teacher. Undoubtedly many of the students had received little or no prior religious instruction, for one teacher of boys, T.C. McKennee, wrote in 1845:

“I had not expected to find, in the nineteenth century, and in the city of New-York, so many children so entirely ignorant of the fundamental doctrines of the christian religion.”

By all accounts, the food at the House of Refuge was nourishing and adequate. The children were fed meat once daily. In 1860, one New York Times reporter commented,

“We are inclined to believe that the food, both in quality and quantity, is better than that of the laboring classes generally.”

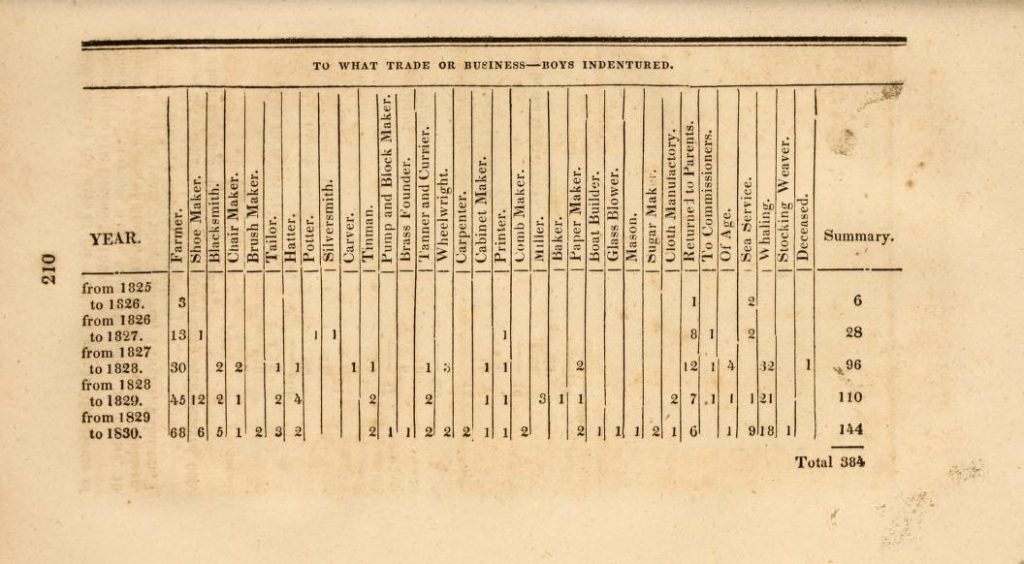

All children admitted to the House of Refuge were “trained in habits of industry.” Boys were instructed in such useful trades as shoemaking, tailoring, and chair caning. Girls learned cooking, sewing, and clothing and bedding manufacturing. Any child who rebelled against the strict rules of the institution (and records indicate there were a good number), or tried to escape was subjected to corporeal punishment: whipping; placement in solitary confinement; and the use of leg irons were commonly employed. Black children were not accepted at the institution until 1833.

Charles Dickens Approves

Visitors to the House of Refuge, including Charles Dickens and Frances Trollope, were greatly impressed with the work of the institution. Dickens, in his American Notes (1842), called it a “noble charity,” and a “meritorious and admirable establishment,” which is “always under the vigilant examination of a body of gentlemen of great intelligence and experience.” Deemed a great success, the institution admitted over 1,678 boys and girls between 1825 and 1835. In 1860 alone, 560 children were in attendance.

.

.

Out into the World

Once deemed “reformed,” a resident was then either apprenticed to a trade or returned to his parents (the latter group being those who were most frequently returned for another round of reform). When discharged to their apprenticeships, residents were given a letter that included the following words of advice:

“If you make yourself master of your business, are diligent in your calling, establish a character for truth, honesty, industry and sobriety, you cannot fail to obtain a comfortable living, and to be beloved and respected.”

The House of Refuge boasted in their Annual Reports that within 3 to 5 years after discharge, 75 percent of those “reformed” were practicing a trade.

Seabury Supports the House of Refuge

With his donation of $25 in 1824, Seabury Tredwell became one of the inaugural donors to the House of Refuge. For the following three years he, along with his brothers Adam and George, donated $20; thereafter his donation amounted to $5 annually, earning him inclusion on the list of “Life Subscribers and Donors.”

The House of Refuge closed in 1935. As a pioneer in the concept of juvenile reformatories, it made a lasting impact on the juvenile justice system, and in its early years served as a model for the establishment of reformatories in many other American cities.

On February 21, 1852, Miss Susan N., a former resident of the House of Refuge then apprenticed as a domestic servant, wrote the following to her former matron at the House:

“Mr. and Mrs. S use me as their own daughter, and I feel happy. Tell the girls I hope they will listen to all the good advice I know they receive from day to day. As my time is out in about 8 months, I expect to spend Thanksgiving with you in the Refuge, if nothing happens.”

No doubt Miss Susan N. hoped that at the end of her apprenticeship, she would be asked to remain permanently at the home of her employers. I wonder what her options would be if they did not. We have no way of knowing how things turned out for this young girl, but we may imagine that Susan rang in the New Year of 1853 with some measure of happiness in the fact that she had found a situation with a good family who treated her with respect, support, and perhaps even love. May 2017 bring us all as much!

Sources:

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Dickens, Charles. American Notes. New York: John W. Lovell Company, 1842. www.archive.org. Accessed 01/05/17.

- Hart, Nathaniel C. Documents Relative to the House of Refuge. New York: Mahlon Day, 1832. https://archives.org/details/documentsrelativ00soci_0. Accessed 11/14/16.

- Knapp, Mary. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- “Our City Charities: the New-York House of Refuge for Juvenile Delinquents.” The New York Times Archive. January 23, 1860. www.nytimes.com. Accessed 11/14/16.

- Palmer, A. Emerson. The New York Public School. New York: Macmillan Company, 1905. www.archive.org. Accessed 1/3/17.

- Pierce, B.K. A Half Century with Juvenile Delinquents; The New York House of Refuge and Its Times. New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1869. www.archive.org. Accessed 11/14/16.

- Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents, N.Y.C. Account Book 1841-1846. New York Historical Society Manuscript Collection.

“The Quality of Mercy:” Tredwell Philanthropy, Part 2

by Ann Haddad

The Tredwells’ Good Genes

Between 1821 and 1840, Seabury Tredwell’s wife, Eliza, gave birth to eight children. Considering the primitive medical care available in the antebellum period, and the resulting high rate of infant and childhood mortality, it is remarkable all of the Tredwell children lived to adulthood. Gratitude for their good fortune in light of the risks associated with childbirth may have been the impetus behind the Tredwells’ decision to support the New York Asylum for Lying-In Women (NYALIW).

Poor, Widowed, Abandoned Women

By the turn of the 19th century, many women found themselves struggling alone to support themselves and their children. Two major yellow fever epidemics, in 1795 and 1798, left many of them widowed. The influx of immigrants to New York City led to a population boom, but jobs were scarce for this group.

| . |

Husbands frequently needed to travel far from the city in search of employment. Some never returned. The incidence of alcoholism among the poor increased. As a result, many pregnant women lacked traditional family support, especially when assistance was needed as the time of their confinement approached.

It is ironic that, although America began to take on a sentimental attitude toward motherhood in the late 18th century, moralistic and religious convictions found many pregnant women, especially unwed ones, with no other recourse for medical care except the almshouse at Bellevue Hospital. “Respectable” women sought to avoid this institution, however, as it had a reputation for being a haven for prostitutes and other “degraded” women.

Wealthy Women to the Rescue

In the early 1820s, wealthy women began to focus their reform efforts on women’s causes, such as education and improved health care. In 1823, a group of benevolent women led by Mrs. Arthur Tappan, wife of the abolitionist Arthur Tappan, established the New York Asylum for Lying-In Women. Its aim was to provide temporary accommodations and skilled medical assistance to poor but “reputable” women during their confinement. “Reputable” in this case meant married; in fact, all applicants were screened by a committee, and were required to furnish a marriage certificate and character references to be considered for admission.

Once admitted, a woman was supplied with a bible and a list of rules, which stipulated that she could not leave the building, could not receive visitors, and could not remain longer than four weeks after delivery. Alcohol was forbidden; that which was used for medicinal purposes was kept in a locked cabinet. Emphasis was placed on order, morals, and obedience. To emphasize their noble mission, the board of the NYALIW included the following passage from William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice in their first Annual Report:

“The quality of mercy is not strain’d.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from Heaven

Upon the place beneath: It is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.”

By Women, for Women

Although it employed a resident male physician, the NYALIW was unique in that it was managed and run by women: it had an all-female board, and barred male medical students from entering the institution. Births were attended by either a midwife or the matron. Postpartum care and vaccination of all newborns against smallpox were provided before discharge.

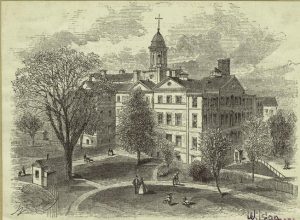

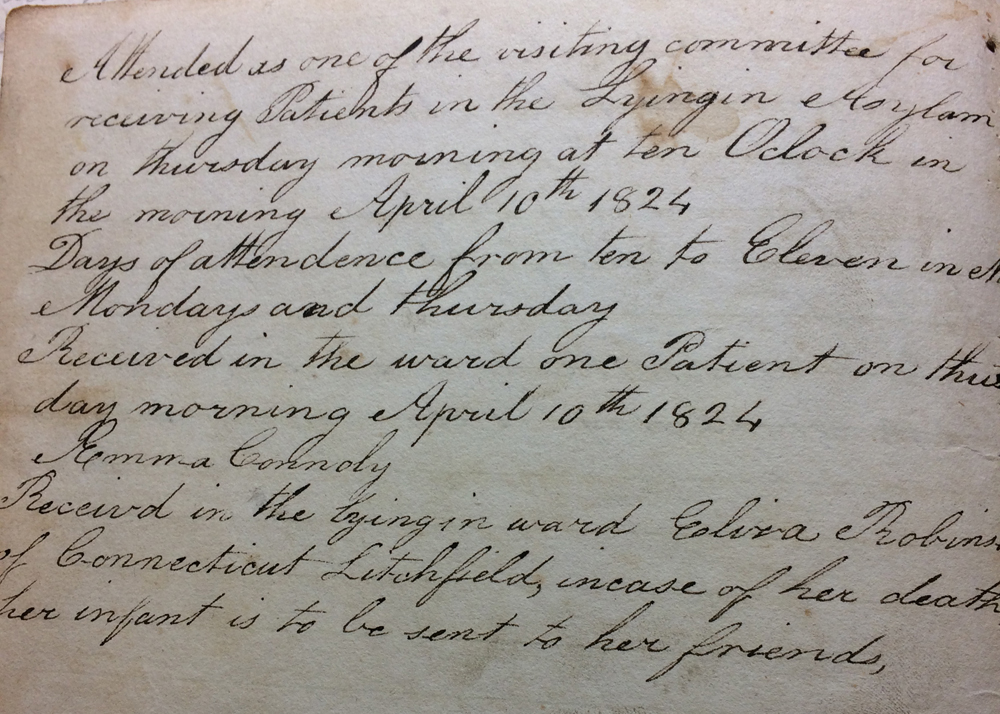

The charity’s first home was the Square Ward of New York Hospital, then located on Broadway between Anthony Street (now Duane Street) and Catherine Street (now Worth Street), which opened for admissions on November 1, 1823. The first patient was Catherine Martin, the wife of a weaver, John G. Martin, who had left his wife three months previous to look for work. Mrs. Martin was admitted on the 21st of November, and gave birth to a healthy child. She was discharged on January 1, 1824.

The Tredwells Support NYALIW

Within a few years the NYALIW outgrew its ward at New York Hospital, and sought donations for the purchase of larger quarters. In 1825, Seabury Tredwell was among the first group of donors, giving $24; the amount collected enabled the charity to move to larger facilities on Greene Street. In 1830, the charity had garnered sufficient funds to relocate to a three story building on 83 Marion Street (now Lafayette Street), where it remained until its move in 1885 to 139 Second Avenue, between 8th and 9th Streets, in the heart of the 14th Ward.

In 1832, Seabury once again donated to the NYALIW. His $25 subscription made him an “Honorable Member for Life,” along with other prominent citizens such as Joseph Brewster, Philip Hone, Duncan Phyfe, and Benjamin and George W. Strong. No doubt the Tredwells felt strongly about this cause, because from 1828 to 1861 Eliza Tredwell, an Annual Subscriber, donated $3-$5/year.

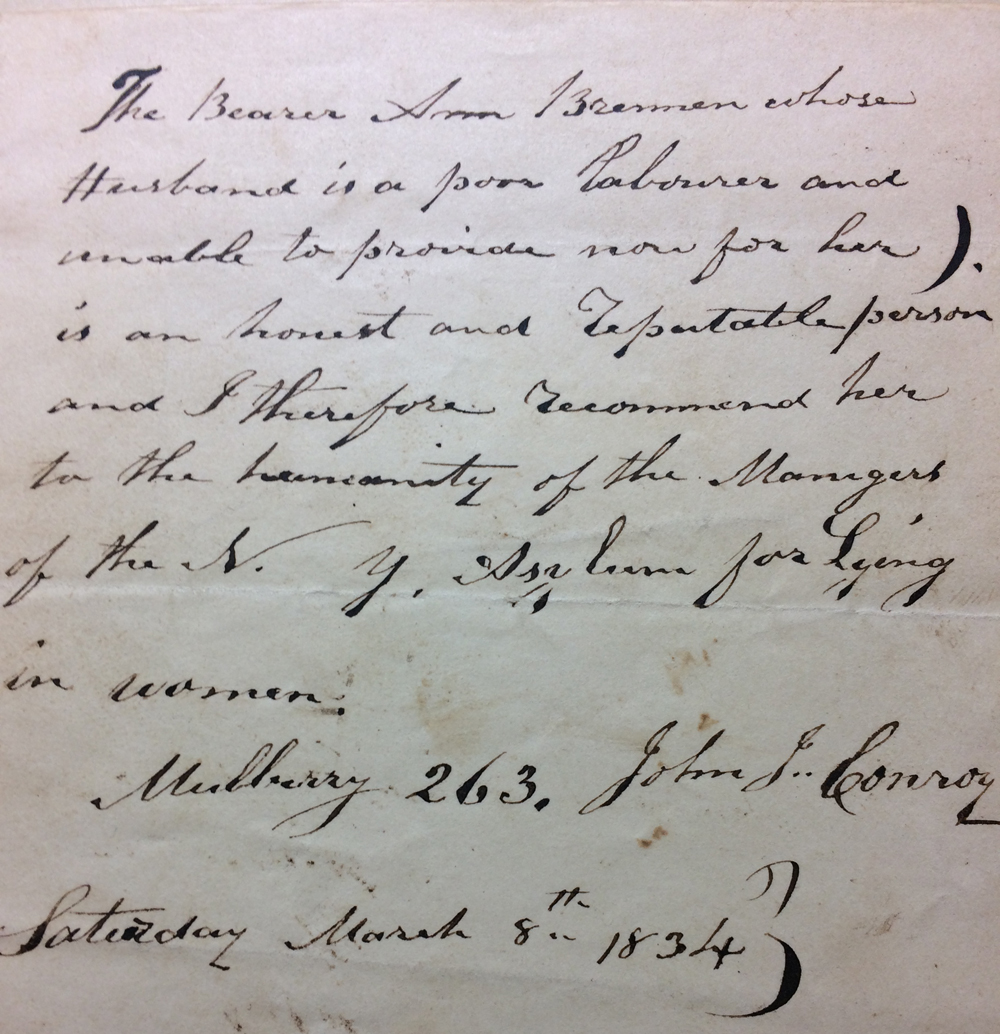

As a Subscriber, Seabury was permitted to recommend two women per year to the institution. One supporter who wrote a letter of recommendation for a woman in need was John J. Connor, who wrote the following:

“The bearer Ann Brennen whose husband is a poor laborer and unable to provide now for her is an honest and reputable person and I therefore recommend her to the humanity of the Managers of the N.Y. Asylum for Lying in women.

Mulberry 263. John J. Connor

Saturday March 8th 1834″

.

Heartbreaking Stories

One story in the NYALIW’s minutes, which is typical of the circumstances that befell many poor women, is that of Mrs. Anne Croaker, who applied for admission on September 13, 1828. Her husband, who had worked as a locksmith for seven years for a Mr. Pye, had recently died. His death was hastened by a dose of arsenic, which was sold in error by the druggist. Mrs. Croaker, left completely destitute, lived with her five young children in a room on Canal Street, which had been loaned by a friend. The Admissions Committee visited Mr. Pye, who vouched for Mrs. Croaker’s character; he stated that she was forced to “sell her most valuable things to procure comforts for him [Mr. Croaker] during his illness.” Mr. Pye generously offered to provide for the children during their mother’s confinement.

Women seeking relief came from Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and outlying parts of New York State. Mrs. Collin Reed, a wealthy New Yorker who served on the Admissions Committee for NYALIW in 1824 and 1825, noted the following in her ledger book:

“Received in the lying-in Ward Eliza Robinson of Connecticut, Litchfield. In case of her death, her infant is to be sent to her friend. [Eliza is] clean and tidy, but very destitute. She supports herself by taking work from the slop shops. Received on the 18th of May, left June 6th.”

In 1831, due to the insufficient numbers of married women who were seeking assistance at the doors of NYALIW, the institution broadened its admission requirements to include unmarried women. It also began making home visits to extend its outreach. For several years previous, however, some committee members had begun to overlook the questionable tales of woe and the dubious marriage certificates furnished by some applicants; thus a number of unmarried women were permitted to enter.

NYALIW’s Employment Agency

| . |

Upon their discharge, the administration sought to place unmarried women as wet nurses in respectable families for one-year periods. After careful screening at the time of admission, observation throughout their confinement, and physical examination by a physician at the time of delivery, the charity was able to offer a guarantee of the health and character of the wet nurses hired by prospective upper class families. In 1828, NYALIW proudly announced that “Of fifty who have been discharged from the house…23 have obtained places as wet nurses in respectable families.” No mention was made of the fact, however, that these women most likely would have had to find a wet nurse for their own infants.

At its 48th annual meeting, held on April 19, 1871, NYALIW reported that since opening its doors, it had gratuitously assisted 16,329 women. It noted that in 1870, 86 patients had been treated at the Asylum, and 188 more at their homes.

In 1894, NYASIW changed its name to the Old Marion Street Maternity Hospital; in 1899, it merged with the New York Infant Asylum. The charity ultimately became the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center.

A Christmas Recipe from 1825

Like many 19th century women, Mrs. Reed, NYALIW’s Admission Committee Member, used her manuscript ledger as a recipe book as well as a diary and account book. Here is her recipe for a festive “Rich Plum Cake”:

Of flour, butter and sugar 3 pounds each, 2 doz eggs, 4 lb and a half of currents 6 lb of raisins, mace, cinnamon, nutmeg each ounce 1/4 oz of cloves, 2 tablespoon full of ginger 2 gills of wine, 1/2 pound of citron.

Wishing you a joyous holiday season! Merry Christmas!

Sources:

- “Anniversary of the New-York Asylum for Lying-In Women.” New York Times. April 20th, 1871, p. 2. timesmachine.nytimes.com. Accessed 12/6/16.

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Golden, Janet. A Social History of Wet Nursing in America: From Breast to Bottle. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Managers of the New York Asylum for Lying-In Women. Annual Reports, 1824-1855. www.archive.org Accessed 11/15/16.

- Minutes, 1823 Nov. 1-1831 Feb. 28. New York Asylum for Lying In Women. BV 89584. New York Historical Society Manuscript Collection.

- New York Asylum for Lying-In Women Materials. Delaplaine Family Papers. 89638. Box 4, Folder 9. New York Historical Society Manuscript Collection.

- Quiroga, Virginia A. Metaxas. Poor Mothers and Babies: A Social History of Childbirth and Child Care in Nineteenth Century New York City. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1989.

- Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice, Act IV, Scene 1.

“The Hand-Maid of Christianity:” Tredwell Philanthropy, Part 1

by Ann Haddad

| . . |

Abundance Rejoices

.

In one of the memorable scenes in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (published in 1843), Ebenezer Scrooge is visited in his counting-house on Christmas Eve by two gentlemen, who are soliciting funds to “furnish Christian cheer” for the poor and destitute. It is essential to do so at Christmas, when “Want is most keenly felt, and Abundance rejoices.”

The men consult a list, which probably contains the names of the wealthy merchants in the area, who might be encouraged to demonstrate their “liberality,” and dig into their pockets. As we all know, the solicitors are sent out of Scrooge’s office empty handed, for the old skinflint insists that the poor turn to the government run workhouses and prisons, institutions his tax money supports, for assistance.

(Don’t take my word for it: see the Summoners Ensemble Theatre’s production of A Christmas Carol in our own Greek Revival parlor, decorated for the holidays, from December 6-24).

.

.

Growth of Reform

The period of economic growth, industrialization, and massive immigration in New York City following the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 led to a great disparity between the wealthy and the working classes, who struggled to survive amidst rising poverty, crime, and disease. Out of moral obligation, philanthropic reformers, including private, evangelical, and mainstream Christian, sought to provide relief and heal society’s ills by establishing countless charities that supported a variety of social causes, some as a direct response to devastating events. For example, the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis in which many lost their jobs or even their entire fortunes overnight, left over 10,000 unemployed city residents with no recourse but to turn to the Central Committee for the Relief of the Suffering Poor, a newly formed government charity. The efforts proved unsustainable, however, due to the huge numbers of the needy, coupled with the influx of poor immigrants.

During the Christmas season, it was customary for the affluent to lavish gifts not only on family members, but also on the impoverished and overlooked poor. Benevolent societies seized upon the sentiments of gratitude and generosity evoked by the season to promote their causes among the wealthy.

Seabury Was No Scrooge

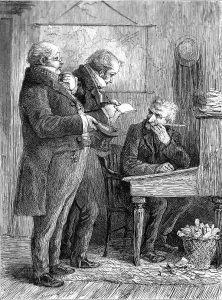

Had A Christmas Carol been set in New York City rather than London, the two gentlemen in search of donations would surely have visited Seabury Tredwell in his hardware store on Pearl Street. As a prosperous merchant, Seabury would have been included on the potential donor lists of the many charitable organizations that existed in the city. In all likelihood, Seabury would have sent the kindly gentlemen away happy, for research has revealed that he supported several charitable institutions throughout most of his adult life. In light of the the holiday season and its consideration as a time of charitable giving, this three-part blog post will focus on those charities that the Tredwell family supported. The first is the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor.

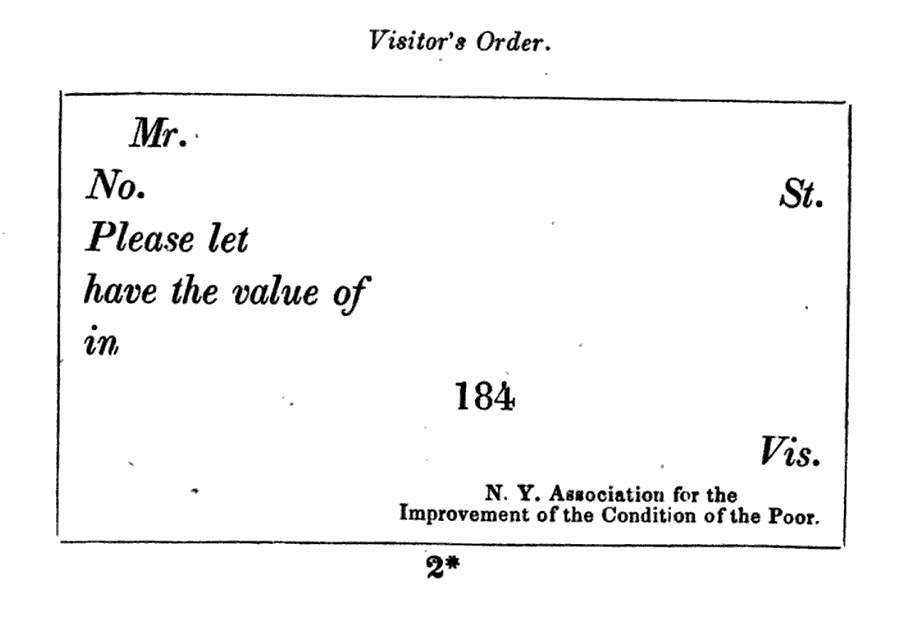

New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor (AICP)

As a reaction to the failures of what they perceived to be defective charitable endeavors, a group of prominent New York businessmen examined the European models of poverty relief. They concluded that due to the lack in oversight of the distribution of charity many imposters were benefitting from the relief intended only for the needy and deserving. In addition, they believed the charitable needed to be educated in ways of giving that would be more beneficial to the recipients.

In 1843, led by Robert Milham Hartley (1796-1881), the group established the New York Association for Improving the Conditions of the Poor (AICP). Hartley believed that the failure of other charitable institutions could be attributed to their lack of discrimination when giving relief; their failure to communicate with one another; and their lack of personal intercourse with the recipients of alms at their homes.

According to its constitution and by-laws, the aim of the AICP was “the elevation of the moral and physical condition of the indigent; and so far as compatible with these objects, the relief of their necessities.” The directors emphasized that charity without moral reform was useless; poverty was the result, not of a failed economic system, but of moral lassitude, which could be rectified by the introduction of values such as self-reliance and pride in one’s efforts; and the promotion of worthy habits such as temperance, industry, and frugality. The AICP devised an elaborate system for the equitable distribution of relief to the “worthy poor.” In this way, they would be able to weed out the fraudulent, or, to separate the “precious from the vile.”

Divide and Conquer

Under the AICP’s organization, the city’s existing 17 wards, or “Districts,” which extended from the Battery to 40th Street, were divided into several hundred sections. Each section had a volunteer “visitor,” who, armed with a “Manual of Rules and Instructions,” was charged with identifying the poor families in need of relief. After ascertaining that the families were truly needy and of good moral character, the visitor was to extend services, provide counsel, and investigate other religious and charitable societies that might be able to assist. Giving money was forbidden, especially to the intemperate. When no other help was available, they were then to draw from the resources of the AICP, but only to purchase food, fuel, or clothing.

Those who failed to pass through the “vast sieve” of necessary criteria to receive assistance were dispatched to the appropriate city agencies. Many of the ill and insane were sent to Bellevue; those who were reconciled to lives of pauperism were sent to the almshouse.

To prevent abuse of the system, the AICP established a central registry of poor families who had received assistance. Visitors were encouraged to engage in “friendly intercourse” with families under their care, and to be an example of the morality they wished the poor to espouse. The AICP described itself as:

“the hand-maid of Christianity, in its endeavors to meliorate the condition of the indigent.”

From 1842-45, the AICP spent nearly $28,000 to aid 8,013 applicants. In addition to the visitor program, it initiated other efforts to improve the conditions in the poor neighborhoods, including the opening of a dispensary, a bathhouse, and a bank. Later reforms focused on children’s health, truancy, the provision of pure milk, and sanitation. In addition, owing to the efforts of member Robert Bowne Minturn, the AICP was one of the early advocates of the development of Central Park.

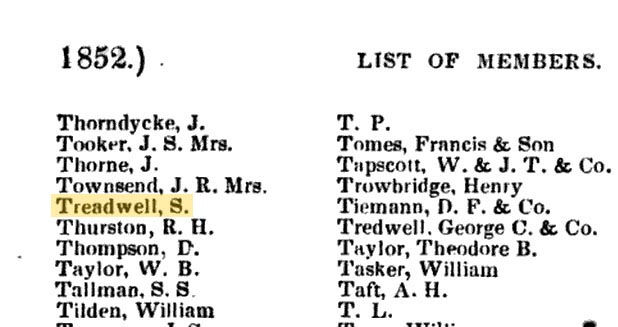

Seabury Supports the AICP

According to the available annual reports, Seabury Tredwell was a member of the AICP, supporting it through monetary donations from 1848 through 1859. His brothers Adam and George Tredwell, who like Seabury were wealthy merchants, were also among the 4,000 contributing members. Membership lists, which read like a Who’s Who of contemporary New York Society, do not include the monetary amount of their donations.

By 1850, the AICP was the most influential charity in New York, and its national renown led to its use as a model for successful charitable reform in many other cities. In 1855-1856, it provided relief to 10,879 families through a total of 43,244 visits. The organization extended its reach to the area of housing reform, opening the Workingmen’s Home on Elizabeth Street in 1855. Described as the earliest “model tenement,” the rental apartments were solely occupied by African Americans, as this group was frequently deprived of adequate housing.

In 1939, the AICP merged with the Charity Organization Society to become the Community Service Society of New York City, which continues its work to this day.

In the AICP Annual Report for 1859-60, a visitor related the story of a destitute woman who, down to “only one dime in the world,” fed herself and her four children. Here are the details in her words:

“Two cents for coke (cheaper than coal)

Three cents for a scraggy piece of salt pork (about 1/2 pound)

Four cents for white beans

One cent for cornmeal

Small as it is, if rightly managed, there is a great deal of eating in one dime.”

Thanks in part to the generosity and benevolence of the Tredwell family, many destitute New Yorkers were provided with relief through the AICP.

Enjoy the holidays! Or, as Tiny Tim exclaimed, “God bless us, everyone!”

Sources:

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Community Service Society. www.cssny.org. Accessed 11/18/16.

- Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. London: Chapman & Hall, 1843.

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

- New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, Annual Report, 1845-1860. catalog.hathitrust.org. Accessed 11/14/16.

- Spann, Edward K. The New Metropolis: New York City, 1840-1857. New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.