Behind Closed Doors & Drawers

In 1835, wealthy merchant Seabury Tredwell purchased this house in the fashionable residential neighborhood known as the Bond Street area, and moved in with his wife, Eliza, their seven children, and four Irish servants. It was the family’s home for almost 100 years.

Gertrude, the Tredwells’ eighth and final child, was born in the house in 1840, never married, and lived in the house her entire life. She died in an upstairs bedroom in 1933, at the age of 93, leaving her home brimming with the family’s possessions from the 19th century. The Merchant’s House Museum’s collection comprises approximately 4,500 Tredwell objects.

Some of the pieces of furniture and household objects may not be familiar to you. What were they used for? What do they look like on the inside? What do they tell us about how the Tredwells lived? Here, you are invited Behind Closed Doors & Drawers for an intimate glimpse of 19th century domestic life in New York City.

Tole (Painted Tin) Plate Warmer, ca. 1820

| … | |

|

|

| … | |

MHM 2002.2430

In the 19th century, rooms were often poorly heated, the only warmth coming from the fireplace, even in wealthy homes like the Tredwells. In order to serve the family food that was hot, or at least warm, the servants heated the plates first.

The plates were warmed either in the kitchen, in the cook stove, or in fancy plate warmers, such as this one (above, left), suitable for a dining room. The back of the plate warmer (above, right, shown with the door open) faced the fireplace exposing the plates to the warm fire. The servants removed the plates through the door on the front of the plate warmer.

The Tredwells’ tole (painted tin) plate warmer sits on the hearth in the family room. Over decades of use, it has worn footprints into the marble (below) from the weight of heavy plates inside.

Cast Iron Coal Cook Stove, 1845-1855

| … | |

|

|

| … | |

MHM 2002.2428

Today, stoves are a snap to use – turn up the heat to the desired temperature, put the food in the oven, or on the stove top, and remove it when it’s done. In the 19th century, cooking on a stove was a far, far more arduous task.

In 1832, when the Merchant’s House was built, cast-iron cook stoves were already available, but it was such a new and untested technology that the builder of this house (who planned to sell it) provided an open hearth for prospective buyers, which was the way people had been cooking for centuries.

By the 1850s, the design of cook stoves had improved dramatically and their convenience better understood such that they had become fixtures in merchant-class homes. It was then that the Tredwells installed a cast-iron coal-burning stove in their kitchen fireplace. To the right and left of the central firebox is an oven, regulated by dampers at the sides of the stove. The pan at the bottom caught the ashes from the coal.

Using the two ovens as well as the flat stove top, where the heat was concentrated on just one side, the cook could prepare foods at different temperatures based on where the pot or pan was located.

But stoves lacked temperature gauges or numbered dials (as we have today), so the Tredwells’ cook checked the oven temperature with her hand. The oven was hot enough to use if she could hold her hand inside for 15 to 20 seconds. If she could keep her hand inside for more than 30 seconds, she needed to add more coal.

In spite of the convenience, preparing food on a cook stove was an onerous job for the Tredwells’ cook. She had to remove ashes from the stove at least twice a day and adjust the flues and dampers before lighting a fire. Stoves were messy, spewing coal smoke and soot everywhere, so after cooking, the Tredwells’ cook had plenty of cleaning to do. She may also have been instructed by Mrs. Tredwell to rub the stove with black wax to remove rust and keep it polished. A servant often spent about four hours each day tending to the stove.

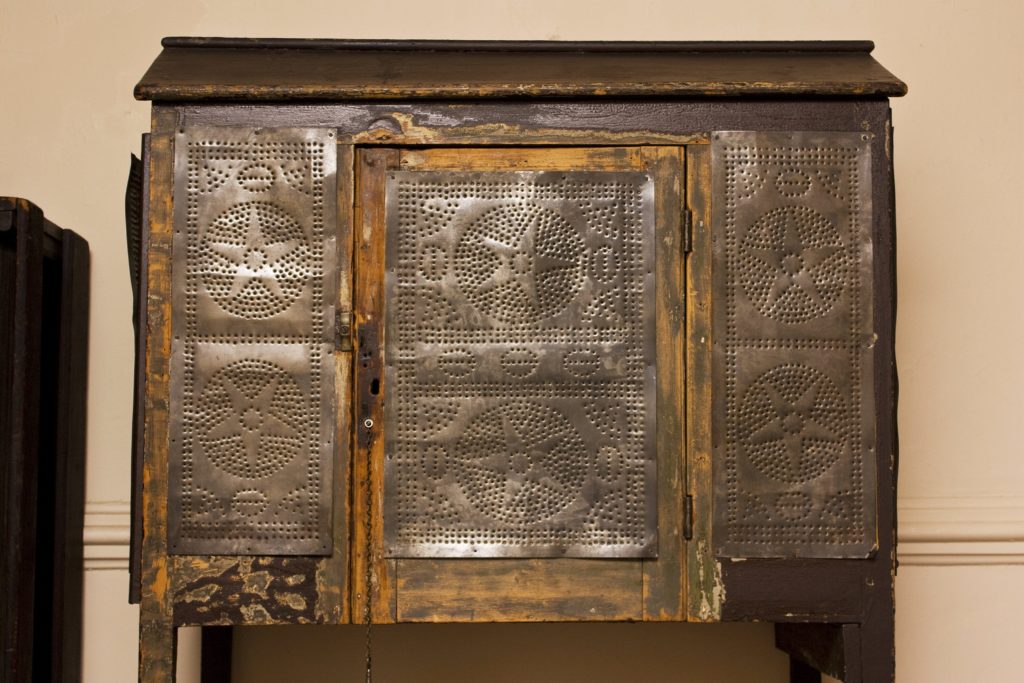

Pie Safe, 19th century

| … | |

|

|

| … | |

MHM 2002.2004

The pie safe was used to store baked goods and is believed to have been first introduced into the United States by German immigrants in the early 19th century. It quickly became a popular and relied-upon piece of kitchen furniture, used to protect freshly baked goods from insects, rodents, and dirt, constant annoyances in 19th century kitchens.

The tall legs of the pie safe were placed in bowls of water to prevent insects and other pests from climbing up. The punctured tin panels allowed air to circulate inside, keeping baked goods cool and preventing mold growth.

The Tredwells’ pie safe, which features decorative tin panels in the design of stars, no doubt got much use in a family of eight children. The door on the pie safe also has a key, an extra measure of protection, perhaps from a Tredwell child in search of a sweet?

Mahogany Door, 1832, Front Parlor

| … | |

|

|

| … | |

The Merchant’s House is one of only 120 designated interior landmarks in New York City, and one of only 6 homes. It is considered one of the finest surviving examples of Greek Revival architecture, fashionable in New York City in 1832, when the house was built. The style is characterized by an emphasis on symmetry. The two rooms of the Tredwells’ first floor double parlor are mirror images of one another in the placement of doors, windows, fireplaces, center plaster medallions, and the plaster moldings. The effect is one of simplicity, harmony, and balance.

The double parlor features four nine-foot mahogany doors. In the rear parlor, two doors lead out to the hall; in the front parlor, one. The fourth door (above, left) in keeping with the fundamental principle of the Greek Revival style, symmetry, is a false door. Shown open (above, right), it exposes the back side of the vestibule wall, which is composed of narrow wooden slats (lath) smoothed over with plaster. To create the vestibule wall, the plasterer applied a slight pressure to push wet plaster through the spaces between the lath. The plaster slumped down on the inside of the wall, forming plaster “keys.” These keys held the plaster in place.

Joseph Brewster, who built this house, acted as his own architect, as did most of the independent builder/developers working during this time. They worked from designs printed in style books by contemporary architects such as Minard Lefever and Alexander Jackson Davis. And they most certainly adhered to the style demands of the period.

Flame Mahogany Sideboard, ca. 1830

| … | |

|

|

| … | |

MHM 2002.2018

Sideboards were fixtures in 19th-century dining rooms, used to store linens and serving dishes and as a place to put dishes during the meal service. They were utilitarian and highly decorative. The Tredwells’ ca. 1830 mahogany sideboard in the rear parlor employs both hand carving and extensive use of figured veneer as ornament. The distinctive and elegant grain pattern of flame mahogany was created by cutting a tree at the join between the trunk and a branch.

A “service” shelf pulls out on the right side (above, right) for holding a lamp or candle holder or to provide an additional preparation area. The deep central drawer (below) has wooden compartmental separations for wine or liquor bottles.

The Tredwells likely bought this sideboard for their previous home on Dey Street before moving to this house in 1835.

| … | |

|

|

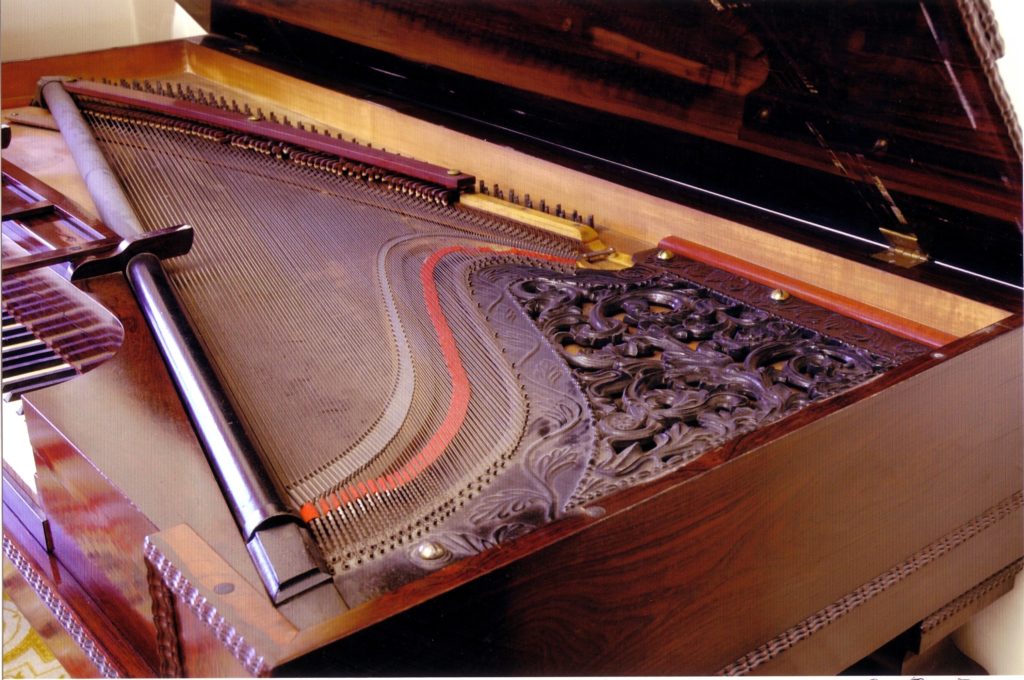

Rosewood Pianoforte, 1846-1848

| … | |

|

|

| … | |

MHM 2002.2027

Music was an important part of social life in the 19th century, and proper young ladies were expected to learn to play the piano. Having one in the home was was a status symbol, reflecting high social standing. The Tredwells purchased this handsome rosewood pianoforte in the late 1840s. It has pride of place in the front parlor.

The Tredwells’ pianoforte was made by Nunns and Fischer, a piano maker located on Greenwich Avenue and Dey Street, not far from the Tredwells’ former home. It is a “square piano” (although not really square) and, with only six and a half octaves, was typical of domestic pianos of the 19th century.

The metal tube on a diagonal (above, right) is called an iron strut, and was invented in England around 1825. The strut supports the frame of the piano and helps distribute the weight from the string tension.

The Tredwells’ piano is unusual in that it has a leather bellows, which when operated with the long pedal at the extreme left (below, left), sends air through a set of reeds, producing a sound similar to an organ. The harmonium reeds are stamped with patent information: “J.S. Ives Patent / May 9, 1846.” Since the firm of Nunns and Fischer was dissolved in 1848, the Tredwells’ piano can be definitively dated to 1846-1848.

| … | ||

|

… |  |

| … | ||

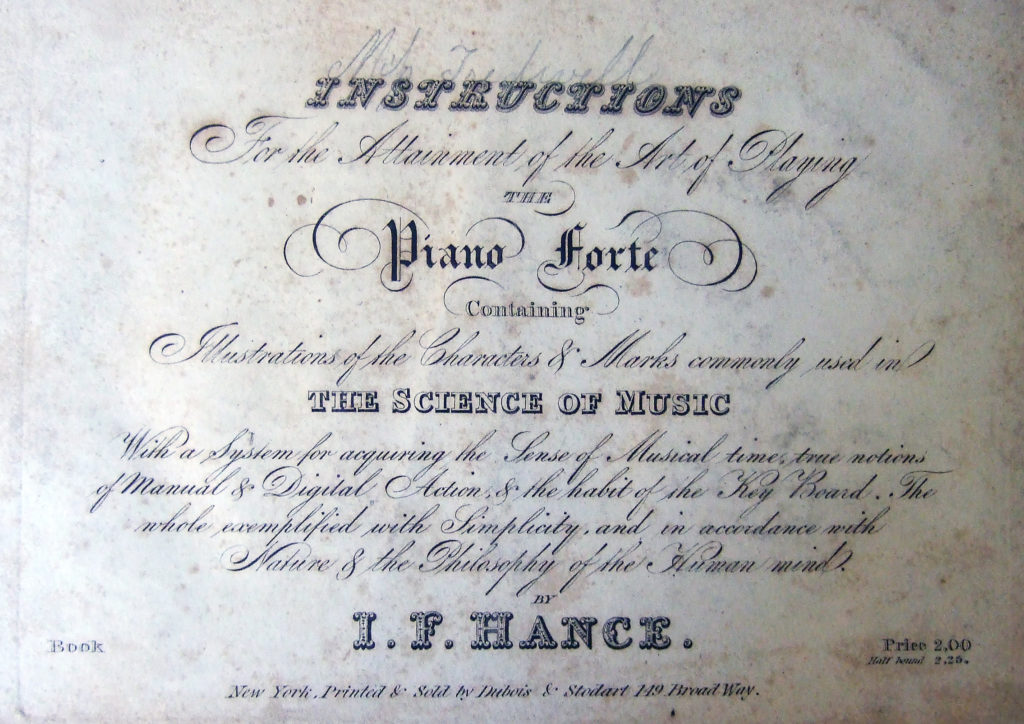

The Tredwell collection contains a book of piano music, Instructions for the Attainment of the Art of Playing the Piano Forte (MHM 2005.6100; above, right) that belonged to Elizabeth Tredwell, the eldest Tredwell child. Just how accomplished the Tredwell sisters were as pianists, we are unable to say.

Mahogany Armoire, 1825-1835

| … | ||

|

|

|

| … | ||

MHM 2002.2031

In 1835, the builder’s advertisement for this house boasted “every modern convenience,” which included bedroom closets, not a common amenity in homes at the time. Most people relied on an armoire, a wardrobe, or standing closet, to store clothing. The Tredwells likely purchased this impressive mahogany armoire for their previous home on Dey Street, which probably did not have bedroom closets for clothing storage.

The armoire (above, left) with its elaborately hand-carved “lion’s paw” feet and hand-carved Ionic scrolls with Corinthian acanthus leaves, features open shelves at the bottom, two drawers in the middle, and three shelves on the top that pulled out to easily place folded clothing.

On the right side of the armoire (above, right) is a door that opens to a narrow space with hooks for hanging clothes. The shelves were added at a later date.

Notice the burn mark on the edge of second shelf from the top (below), likely caused by a candle left unattended on the shelf below.