Romance and Sweet Dreams: Mid-19th Century Courtship

by Ann Haddad

.

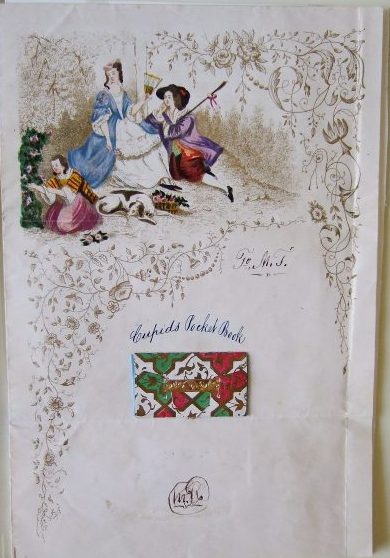

Valentines for an Eligible Lady

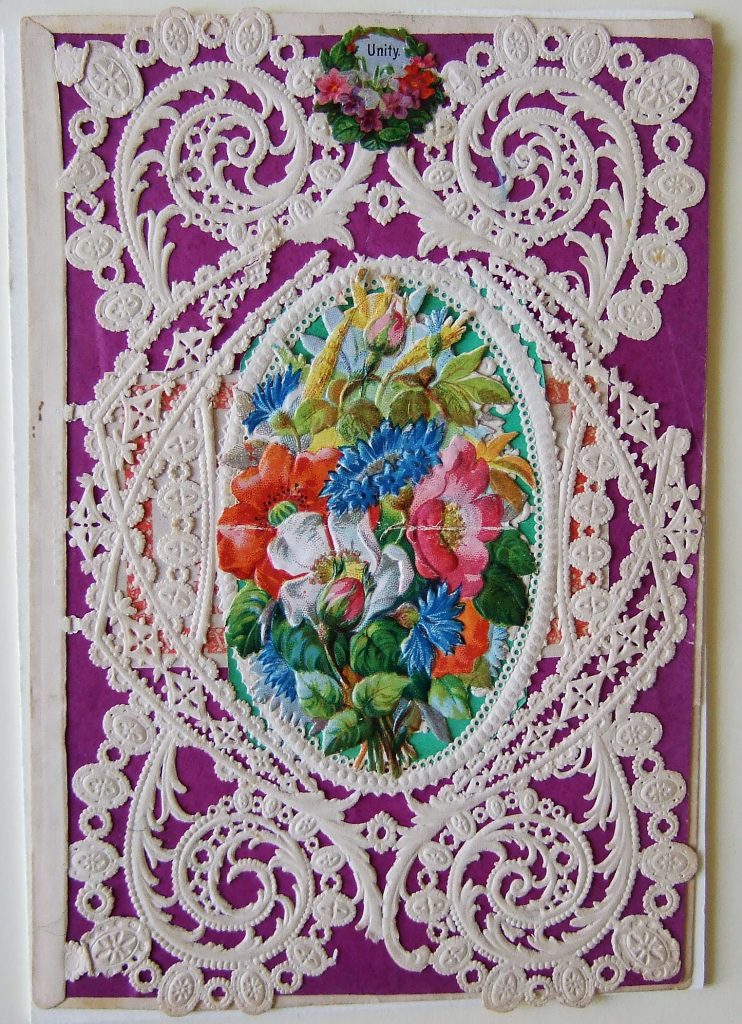

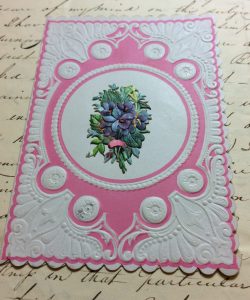

Valentine’s Day has been celebrated for centuries, but only became entrenched in American culture in the early 1840s, with the rise in popularity of commercially produced paper valentine cards. Made of delicately embossed and perforated lace papers, valentines became the fashionable way to convey romantic interest and to freely express the desire for romantic love.

The lovely Elizabeth Tredwell, eldest daughter of Seabury and Eliza, no doubt received her share of valentines from young men of her class. She was pretty and accomplished, and would certainly have been considered an eligible young lady. The Tredwell Archives contain several charming valentines; however, the senders and recipients are unknown.

On April 9, 1845, Elizabeth married Effingham Nichols (see our April 2017 blog post, “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing: The Marriage of Elizabeth Tredwell and Effingham Nichols”). We do not know when and how Elizabeth and Effingham met, nor are we aware of the length of their courtship. Based on the many strict codes of etiquette that governed courtship, however, we can assume theirs followed a dictated course.

.

.

.

Romantic Love

In the mid-19th century, romantic love was viewed as the solid rock upon which a healthy marriage was built; according to Karen Lystra, author of Searching the Heart (1989), it was only within the sacred state of marriage that one’s “ideal self” could be revealed. Courtship, therefore, was respected as a special time in the lives of a young couple. This period, after introductions and before a formal engagement, served to intensify the feelings of romantic love; to insure that the bond formed between a couple was true; to guide one in learning the real character of the other; and to ensure that their attraction was based on mutual respect and admiration. In Theocritus’ The Dictionary of Love (1858), it is defined as the period that is “all romance, excitement, hope, desire, expectation, and sweet dreams.”

Before Courtship: Under Mama’s Watchful Eyes

The time for a young woman to enter society and assume her role as a marriageable woman was determined by her parents; it depended not on her age, but on her level of maturity. A woman was also expected to have completed her education, or “finishing,” typically between the ages of 16 and 18, before entering society. Elizabeth most likely went “into company” (or “came out,” as it was later called) sometime around the age of 20.

Courting before this age was highly frowned upon. After completing her schooling, a daughter remained at home (which was viewed as a woman’s empire), under the watchful eyes of her mother. Here she learned domestic arts; assisted with rearing her younger siblings; and was instructed in the rules of manners and civility, which were highly valued in society. A young lady was chaperoned at public entertainments, such as theatre or dances, by her parents, brothers, or an intimate family friend. (Once she became formally engaged, her lover became her “legitimate protector and companion.”) She was expected to rebuff any male attention, and maintain a polite disinterest in courtship. Mrs. John Farrar, in A Young Lady’s Friend (1837), writes,

“The less your mind dwells upon lovers and matrimony, the more agreeable and profitable will be your intercourse with gentlemen. Regard men as intellectual beings who have access to certain sources of knowledge to which you are denied.”

Elizabeth also received guidance from her mother (likely culled from popular advice books such as Lydia Maria Child’s The Frugal Housewife (1829); Godey’s Lady’s Book; and etiquette and conduct manuals) about acceptable behaviors that reflect what Mrs. John Farrar called “delicacy and refinement” when in the company of young men. Never let a man hold your hand; decline his offer of assistance with getting in and out of carriages; never squeeze into a tight space with a gentleman; never speak of your private affairs or feelings; always have a friend present for carriage rides; never borrow money from a man; avoid gossip. Mrs. Farrer stressed:

“Your whole deportment should give the idea that your person, your voice, and your mind are entirely under your own control. Self-possession is the first requisite to good manners.”

Above all, a young lady was never to make obvious public plays for the attention of a young man, or insinuate that she wanted an invitation from him. According to T.S. Arthur, author of Advice to Young Ladies (1847), such inappropriateness indicated “an outrageous want of all decent respect for herself.”

Money and Religion

Aside from the usual parental concerns associated with finding a suitable partner for their daughter, Seabury and Eliza Tredwell had another reason to be extremely careful when vetting young men who were interested in courting Elizabeth: the family’s enormous wealth. Guarding against any unprincipled suitor who viewed a fortune as indispensable when choosing a wife was no doubt of utmost importance. They therefore sought to find a husband for Elizabeth whose own wealth was equal to or greater than her own. Similarity of religion was also considered to be a requisite; whoever sought and won Elizabeth’s hand had to be of the Episcopal faith (see our February 2017 blog post, “The Man That Got Away,” for a discussion of the aborted romance of Elizabeth’s youngest sister, Gertrude, and Luis Walton).

A Formal Introduction

A gentleman did not consider courting a woman unless he had been formally introduced to her. (Men were not without their etiquette manuals: Lord Chesterfield’s Advice to His Son on Men and Manners, first published in 1774, was the popular source.) Effingham may have been introduced to Elizabeth through her father or one of her uncles, or through a respected friend of the family. For those without known connections, it was the gentleman’s task to respectfully make her acquaintance. Upon noticing a woman at a dance, for example, he first learned her name by making discreet inquiries, and then, through his societal connections, asked for an introduction. As the couple became acquainted through conversation, the gentleman ascertained the woman’s level of interest, and whether any further attentions were welcome.

Dear Mr. Tredwell

If he perceived that she was not averse, and he was confident that his position in life and circumstances were sufficient to allow him to proceed, a gentleman took the next step — writing to the woman’s father to ask permission to pay a visit to their home. In this important communication, he stated his position and prospects, and mentioned his family. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852) cautioned the suitor against any smugness or over-confidence at this stage:

“Never think you are doing the family a favor. A man must convey delicate respect towards the parents, to prove himself worthy of the treasure of which he is about to deprive them.”

The following portion of a sample letter from The Art of Good Behavior (1845) may be similar to one sent to Seabury Tredwell from Effingham Nichols, when he desired to begin courting Elizabeth:

“The subject upon which I presume to address you is one so near to my heart, and so connected with my prospects of happiness in this life, that I find it difficult to summon resolution for the task; but sir, I have dared to entertain so high an opinion of your goodness, that I am emboldened to write to you with candor, to solicit the greatest favor it is in your power to bestow.”

Emily Thornwell, in The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility (1856), defined the proper look of a letter from a potential suitor to a young woman’s father:

“Observe that letters of introduction are never sealed by well-bred people. Every letter to a superior ought to be folded in an envelope. It shows a want of respect to seal with a wafer; we must use sealing wax; men usually select red.”

Once permission was obtained from the father, the young lady in question then extended a letter to the gentleman, inviting him to pay a call. She avoided displaying any excessive interest in him, however. Thornwell emphasized the importance of restraint:

“You should not remark to a gentleman, ‘I am very happy to make your acquaintance;’ because it should be considered a favor for him to be presented to you, therefore the remark should come rather from him.”

The Trial Period

As soon as the father established that a young gentlemen was suitable company for his daughter (accomplished through inquiries among his set as to the family and status of the suitor), courtship commenced. In the young lady’s front parlor, with a chaperone present, a courting couple engaged in allowed activities including singing, talking, piano playing, and parlor games with other guests. Supervised carriage rides and outdoor excursions to dances, picnics, dinners, and concerts were also permitted. During this time, the couple observed one another’s habits and conduct for evidence of good moral character and virtuous principles, and hence suitability.

A woman considered positive traits, such as a man’s ability to speak with ease, respect, and courtesy to all; a neat appearance; excellent manners and deference to all women; and his readiness to honor and defend the opposite sex. Among the negative qualities that put a woman on her guard, as noted in The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony, were:

“Keeps irregular hours

His studies do not form the subject of his conversation, as bearing on his future prospects

Shows disrespect for any age

Laughs at things sacred

Absents himself from regular attendance at church

Shows an inclination to expensive pleasures, or to low and vulgar amusements

Betrays a desire for enjoyments beyond his means or reach

Makes his dress a study

Betrays a continuous frivolity of mind.”

Etiquette manuals were replete with warnings to young ladies to beware being dazzled by “morally depraved” men or, as stated in Advice to Young Ladies:

“A young lady should be careful that brilliant qualities of mind, a cultivated taste, and superior conversational powers, do not overcome her virtuous repugnance to base principles and a depraved life.”

The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony also provided guidelines for gentlemen as they waded into the murky waters of courtship. A woman who was kind, patient, benevolent, peaceful, and charitable; and who enjoyed home-centered pleasures, was worth pursuing. But a gentleman should “retire speedily but politely” from a woman with any of the following traits:

“Has the heartless buzzing of a flirt

Gives smiles to all and a heart to none

An uneven temper

Is fond of dress, and eager for admiration

Is ecstatic in trifles and nonsense, and frivolity

Is weak in her duties

Is petulant, saucy, or insolent

If the holiness of religion does not hover like a sanctifying dove ever over her head

Is prideful, boasting, vane, sharp rather than quiet

Gaudy”

When choosing to cast his eye upon a young lady with views toward matrimony, a gentleman needed to be mindful of the following:

“You do not catch us by mere beauteous look,

Tis but the bait, floating without the hook.”

Despite all these dire warnings, the author ended on an uplifting note:

“In nine out of ten cases it will be found that some demonstration of gentleness, benevolence, devotion, or self-sacrifice will invariably have been the foundation and first cause of serious thoughts of matrimony.”

No Gifts, Please

Another rule of courtship prohibited a young lady from accepting presents from a gentleman, prior to his having made a distinct proposal of marriage. It was considered improper and unbecoming, and implied an obligation on her part. Should the gentleman insist on her accepting a gift, she was to acknowledge its receipt in the presence of her parents, thereby removing any trace of impropriety. Any gifts received anonymously were put away and never mentioned. According to T.S. Arthur’s Advice to Young Ladies, flowers, fruit, and candy were the only acceptable presents from a young man to a young lady prior to their engagement, because:

“their perishable nature exempts them from the ban put upon more enduring memorials.”

Love Letters: “The Sweetest Things”

With all the restrictions placed upon young lovers during their courtship, letter writing became the allowed means by which they could express their feelings, continue the process of getting to know one another, and hopefully, fall in love. In the mid-19th century, suitors had at their disposal numerous letter-writing manuals that offered sample letters for every occasion, including expressions of romantic love and marriage proposals. In The Dictionary of Love (1858), love letters were referred to as, “among the sweetest things which the whole career of love allows.” The author of The Art of Good Behavior wrote: “The delicate and interesting preliminaries of marriage are oftener settled by the pen, than in any other manner.”

Love letters were considered sacred and sincere testaments to a couple’s love; such intimate correspondence was regarded with respect and a deep sense of privacy. A family member would never open a daughter’s or sister’s love letter; upon receiving it she retired to her room to read its contents in private.

It comes as no surprise to learn that rules governed the writing implements, paper, and even stamps, for love letters. The Art of Good Behavior insists:

“For a love letter good paper is indispensable. When it can be procured, that of a costly quality, gold-edged, perfumed, or ornamented in the French style, may be properly used. The letter should be carefully enveloped, and nicely sealed with a fancy wafer – or what is better, plain or fancy sealing wax. The whole affair should be as neat and elegant as possible.”

We have no surviving love letters between Effingham and Elizabeth. Perhaps one might have been similar to the following, from the Butler-Laing Family Papers (NYHS), written in 1861 by Frank Butler to his cousin Mary:

“My dear Cousin if you could only realize how deep an attachment I have found for you, and how sincerely and fondly I have learned to love you, even from the very first hour of our meeting, you might then imagine the thought of being so wholly separated from you, for how long a time God only knows, can be attended with painful feelings only.

Goodbye Mary, and may God bless you and the other members of the happy family with which you are connected. And may you sometimes, in your nightly visions think of one who holds you in highest admiration and unlimited affection.

Devotedly your cousin,

Frank Butler”

Another, unsigned and undated, from the Emily Hosack Rodgers Collection (NYHS), indicated the freedom a gentleman felt in writing to his love interest:

“If you love me, I will seek only to enfold your whole existence within the arms of a true and devoted love. With the true wisdom of an affectionate heart I will only seek, will only desire to find my own happiness in yours.”

A Valentine’s Day Poem

The Obituary Record of Yale University (1902) mentioned that Effingham Nichols wrote poetry and prose. Perhaps he sent a valentine poem to Elizabeth during their courtship. It may have been similar to this one, “Friendship Offering” (NYHS), written in 1832 to Anna Brooks:

“If though thinkest, Anna

That I shall complement thee now,

And say how well you play on the piano,

And praise the brightness of thy brow;

Or tell thee that thy voice is sweet,

Or that thou hast a lovely face,

Or snowy hands, or pretty feet,

Or complement one single grace,

That throws its glory o’er thy manner,

Or even praise those eyes of thine!

Thou art indeed mistaken, Anna;

Although in every Valentine,

I know thou hast a right to think

Such praise would be given to thee;

But thou! oh, thou couldst never drink,

Deep of the cup of flattery:

For in the depths of thy young mind,

Life’s holiest treasures are enshrined.

Learning and wit, and beauty bright,

And virtue – charms that alone delight

The soul – Yes! All these blessed gifts are thine.”

Our next blog post will address the rituals surrounding marriage proposals and engagement. Happy Valentine’s Day!

Sources:

- Anonymous. The Art of Good Behavior, and Letter Writer, on Love, Courtship, and Marriage: A Complete Guide. New York: Huestis & Cozans, 1845. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society.

- Anonymous. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony. London: David Bogue, 1852. books.google.com. Accessed 1/18/18.

- Arthur, T[imothy]S[hay]. Advice to Young Ladies on Their Duties and Conduct in Life. Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1847. babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 1/16/18.

- Brooks, Anna. Valentine’s Day Poem, 1832. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Butler-Laing Family Papers, 1818-1892. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Emily Hosack Rodgers Collection, 1848-1888. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Farrar, Mrs. John. A Young Lady’s Friend. Boston: American Stationers’ Company, 1838. internetarchive.org. Accessed 1/23/18.

- Halttunen, Karen. Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

- Knapp, Mary L. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- Lystra, Karen. Searching the Heart: Women, Men, and Romantic Love in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Rothman, Ellen K. Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1984.

- Theocritus, Junior [pseud.]. Dictionary of Love. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1858. internetarchive.org. Accessed 1/22/18.

- Thornwell, Emily. The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility: In Manners, Dress, and Conversation. New York: Derby & Jackson, 1856. internetarchive.org. Accessed 1/17/18.

- Valentines. American Antiquarian Society. americanantiquarian.org. Accessed 1/24/18.

- Yale University. Obituary Records of the Graduates of Yale University Deceased from June,1890 – June, 1900. New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1902, p. 672.

The Man That Got Away: Gertrude’s Lost Sweetheart

by Ann Haddad

An Abundance of Daughters

By anyone’s measure in antebellum New York City, the Tredwell daughters would have been viewed as highly desirable marriage prospects. As the children of Seabury Tredwell, a wealthy merchant with a fine home in the elite Bond Street neighborhood, they stood to inherit a portion of their father’s estimable worth. They counted among their social circle other members of the New York City upper class, and would have mingled with many eligible young men at the frequent soirées held at one another’s homes, or at other socially acceptable venues.

Party Girls

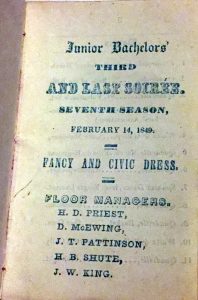

The Museum archives contain several items, including dance cards and playbills, that provide a glimpse of the Tredwell daughters’ social whirl. One is a silver Valentine’s Day dance card from the “Junior Bachelor’s Third and Last Soirée,” dated February 14, 1849. The lovely dresses in the Museum’s collection that belonged to the sisters indicate that they had the means and the sophisticated taste to keep up with fashion trends.

A Gentleman Caller

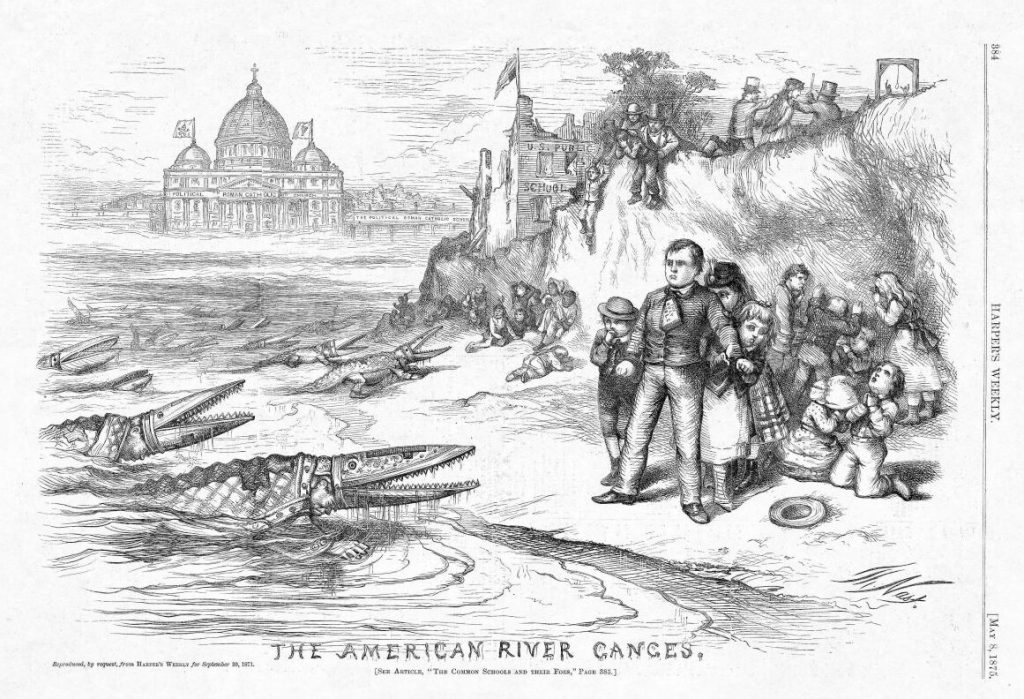

Gertrude Ellsworth Tredwell, born in 1840, was the youngest child of Seabury and Eliza. Family lore has it that when she was a young woman, Gertrude had a suitor whose name was Luis Walton. We don’t know if Luis ever had the opportunity to enter the Tredwells’ formal Greek Revival parlor to meet Gertrude’s father, and perhaps ask for her hand in marriage; however, we can be fairly certain the young man had three strikes against him. First, Luis’ father was a physician, from England. Physicians, especially those trained in England, were held in much lower esteem than they are today. Moreover, Seabury, a believer in homeopathy (see my blog post of October 18, 2016), might well have cringed at the idea of an allopath like Luis’s father becoming a member of his family. Second, Luis and his family were Roman Catholic. The Tredwell family came from a long line of staunch Episcopalians, and anti-Catholic prejudice ran deep in antebellum New York.

Finally, his mother was Irish; well, the Tredwell servants were Irish! The Irish were on the lowest rung of the social ladder; the contempt towards members of this large immigrant group was strenuous and prevalent. Surely, Luis could not expect to meet Seabury’s high standards of eligibility for Gertrude’s hand in marriage. And so, after his brief appearance on the Tredwell stage, Luis Walton vanished forever. Or did he?

A Liverpool Lad

Luis Puertas Richard Walton was born in Liverpool, England on November 18, 1840. The England census record of 1841 indicates that at the time of Luis’s birth, the family had a boarder named Luis Puertas, who was listed as a “cigar dealer from foreign parts.” This must have been Luis Walton’s namesake!

Luis’s father, Henry Christmas Walton, was a licensed physician and apothecary. His mother, Elizabeth, was from Ireland. In 1849, Luis was baptized Roman Catholic at the Church of St. Peter in Liverpool.

A Neighborhood Boy

Life must have been difficult for the Walton family, for in 1844 Dr. Henry Walton declared bankruptcy in London. This may be what compelled him to immigrate to New York City in 1850 with his wife and four children, when Luis was 10 years old. The family’s first identified residence was on 590 Houston Street, on the corner of Mercer Street, a short walk from the Tredwell home on East Fourth Street. From there they moved to West 10th Street. By 1860, the family was comfortably ensconced in their own home on 37 West 16th Street, with five servants in their employ, indicating that the family’s financial situation must have vastly improved. We don’t know if Seabury was aware of their good fortune, but the young man’s religious and cultural disadvantages most likely prevailed in Seabury’s consideration of him as a potential son-in-law.

On to Medical School

We can only guess that Gertrude and Luis, living in such close proximity to one another, met somewhere in the neighborhood through mutual friends. We don’t know if they saw each other once Seabury expressed his disapproval. Luis may have been discouraged, but he clearly wanted to make something of his life. He pursued an education at Columbia College (then at Madison Avenue and 49th Street), earning his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1861, and three years later a Masters of Arts degree from the same institution. In 1870, after a two year course of study, he received his M.D. from the prestigious Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons (then located at 4th Avenue and 23rd Street). His father was one of his preceptors during his medical training.

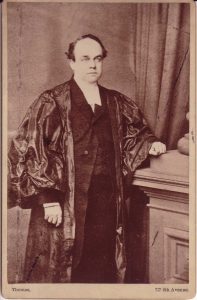

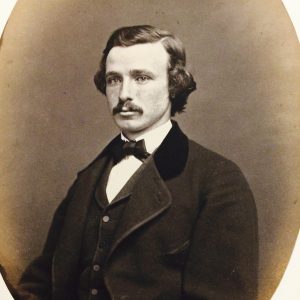

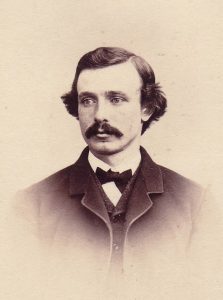

.

A Successful Medical Career

Luis became a successful physician in New York City. After medical school, he resided and practiced for several years on West 17th Street; he then lived at various residences in the West 30s, until his final move to 73 West 50th Street, where he lived and maintained a lucrative general practice until his death. No doubt he followed his well-off private patients as they moved further uptown. He was a member of the Medical Society of the County of New York (1888-1903), as well as the New York Clinical Society.

Friendship with Edward Livingston Trudeau

In addition to his private practice, Luis served as an Attending Physician at both the Northern Dispensary (at Christopher Street and Waverly Place), and the Demilt Dispensary (at Second Avenue and East 23rd Street), charitable institutions that provided care to the poor and destitute of New York City. One of his colleagues at Demilt, who co-taught a class on diseases of the chest, was public health pioneer Edward Livingston Trudeau (1848-1915). Trudeau, himself a victim of tuberculosis, would in 1885 establish a famous sanatorium for victims of the disease in Saranac Lake in the Adirondack Mountains and, several years later, the first laboratory in the United States dedicated to the study of tuberculosis. In his autobiography, Trudeau makes frequent mention of Luis Walton, and credits his friend with drawing his attention to the work of the German physician Dr. Hermann Brehmer in establishing the practice of open-air treatment for tuberculosis. On a more personal level, Trudeau reveals Walton’s frequent calls and assistance during his bouts of illness:

“Dr. Walton was the greatest comfort at that time, and assured me he would look after my wife and ‘those dreadful little Trudeau brats,’ and he certainly kept his word. Walton all through the summer made regular pilgrimages to Little Neck [where Trudeau’s family stayed while he was recuperating in the Adirondacks], and reported to me of their welfare, while assuring me what a nuisance it was to have to look after another man’s family.”

Oh, to Be in England

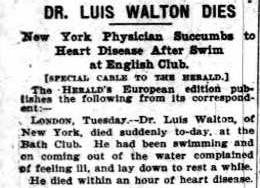

Luis clearly loved the country of his birth. An avid Anglophile, he was a member of the prestigious St. George’s Society of New York, a charitable organization that offered assistance to those born under the British flag. He also made frequent excursions to London, where he was a member of the elite Bath Club in Piccadilly. On September 8, 1903, after a swim at the Club, Luis died suddenly. He was 62 years old. His death was attributed to longstanding heart disease. He was buried at Kendal Green Cemetery in London. He left his estate to his surviving sister, Lucy Walton Mooney. The obituaries in professional journals that appeared at his death indicate that he was a highly esteemed physician, with a kindly manner and a deep compassion for his patients.

.

Lovers Apart?

We do not know the extent to which Gertrude and Luis maintained any relationship through the years. They must have corresponded with one another, for Gertrude referred to him in a letter to her nephew John T. Richards, dated November 18, 1924:

“You know Dr. Walton had “Angina Pectoris” but he lived for years with it – Strained himself climbing the Alps.”

Gertrude also kept in touch with at least one member of Luis’s family. The law firm hired by Gertrude and Julia to manage the estate of Sarah and Phebe Tredwell upon their deaths in 1906 and 1907 was Blandy, Mooney, and Shipman. The Mooney is Edmund Luis Mooney, a nephew of Luis Walton, who was with him in London at the time of his death. Coincidence? What do you think?

Assuming that Seabury’s disapproval of Luis is what precipitated the young man’s disappearance from Gertrude’s life, what kept the couple apart after Seabury’s death in 1865? Why did Gertrude never marry? Tradition has it that she vowed that if she couldn’t wed Luis, she would never marry. Perhaps her mother and older siblings were as much against the marriage as her father had been. Gertrude may have been reluctant to go against his wishes and the predominant Protestant culture of affluence and gentility in which she was raised. Or maybe the answer is simply that she never fell in love with any man after Luis. Whatever their reasons, there is one certainty: neither Gertrude, nor Luis, ever married.

While researching Luis Walton, his 1861 graduate photograph was located in the Class Photograph Albums Collection at Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Museum staff recognized him from a previously unidentified photo in the collection (pictured above). We don’t know how the carte-de-visite of Luis came to be in the Tredwell home, but it remained there for the rest of Gertrude’s life. Valentine’s Day is the perfect occasion to celebrate the star-crossed love story of Gertrude and Luis!

Sources:

- ancestry.com England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975. Accessed 7/29/14.

- ancestry.com England Census, 1841. Accessed 7/31/14.

- ancestry.com New York, State Census, 1855. Accessed 7/29/14.

- ancestry.com United States Federal Census, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900. Accessed 7/31/14.

- ancestry.com U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989: 1902, 1903. Accessed 7/27/14.

- ancestry.com Directory of Deceased American Physicians, 1804-1929, JAMA Citation: 1903:41:736. Accessed 7/27/14.

- ancestry.com U.S. School Catalogues, 1765-1935: 1857-1861. Accessed 7/21/14.

- “Apothecaries Hall.” Lancet. Volume 1, p. 167. Accessed 7/21/14.

- “Bankrupts.” archive.thetablet.uk, pg. 8, 17 August, 1844. Accessed 7/21/14.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons. Catalogue of the Alumni, Officers, and Fellows 1807-1880, p. 122. Archives & Special Collections, A.C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons. Student Registers 1863-64 – 1878-79. Archives & Special Collections, A.C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons. Graduates of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Annual Catalog, 1870, p. 16. Archives & Special Collections, A.C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center.

- Columbia University. Class Photograph Albums Collection 1856-1902, UA#0131, Bib. ID 10278078, Box 79, 1861. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Butler Library, Columbia University.

- Medical Directory of the City of New York. New York: Medical Society of the City of New York, 1887-1900.

- Medical Register of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, 1872, p.158, 159.

- New England Journal of Medicine. Volume 149, September 17th, 1903, p. 332.

- newspaperarchive.com. London Standard, Friday, September 11th, 1903, p.7.

- newspaperarchive.com. London Monitor and New Era. Friday, September 18th, 1903, p. 11.

- Records of the Northern Dispensary, 1827-1955. Series 1, Box 3. New York University Archives, Bobst Library, New York University.

- St. George’s Society. A History of St. George’s Society of New York from 1770 to 1913. New York, [St. George’s Society], 1913.

- Trudeau, Edward Livingston. An Autobiography. New York: Doubleday, Doran, and Company, 1915.