Ladies of Refinement: The Women Who Educated the Tredwell Daughters

by Ann Haddad

Six Tredwell Daughters to Educate!

As the daughters of a prosperous merchant, the six Tredwell girls were granted all the privileges of the elite class in which they were raised, including a private school education. From among the many girl’s schools in New York City, Seabury and Eliza chose two of the best for their daughters – Mrs. Okill’s and Mrs. Gibson’s. [For a discussion of private school education for boys, click here to read “Samuel Tredwell’s School Days,” September, 2017.]

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Mary Jay Okill owed a debt of gratitude to the Tredwell family. Mrs. Okill (1785-1859), was the headmistress of one of the most highly regarded female academies in New York City in the Antebellum era. Seabury and Eliza Tredwell, by entrusting her with the education of all six of their daughters over a period of at least 20 years, demonstrated support for Mrs. Okill’s system of education, at a time when the wealthy and elite families of the City could choose from among many similar private institutions. The decision by the Tredwells to send their daughters to Mrs. Okill’s likely influenced other wealthy families in their circle.

The Finishing Touch Plus Morality

In the first half of the 19th century, the aim of elite female education was to provide young ladies with the social graces and manners befitting their place in society, and to instill a basic knowledge of literature, classics, arithmetic, and geography. Several schools also included instruction in the religious and moral principles that would lead to the development of virtuous, charitable, and benevolent character. This approach, which Mary Okill outlined in detail in her first advertisement for her new academy in the Christian Journal, and Literary Register (1823), certainly appealed to parents such as Seabury and Eliza Tredwell, for it would essentially “finish” their daughters by preparing them for the most important roles within their sphere: those of wife and mother. As the advertisement states:

“… while every attention will be paid to the ordinary and ornamental branches of a finished female education, the department of religious instruction will receive particular care. Mrs. Okill … will devote her time to the superintendence of her school, and to the religious principles, morals, and manners of those young ladies who may be confided to her care.”

So Many Choices!

The single-gender “academy,” copied in style and substance from the British finishing school, was extremely popular among the wealthy of New York City in the early-mid 19th century. Such schools, which occupied rented houses run by a head teacher, typically offered opportunities for both day and boarding school students; the staff, who lived at the establishment, included other teachers, cooks, and domestic servants. Teacher training and curriculum was not standardized. With time and the increasingly progressive nature of female education, the homelike atmosphere gradually transitioned to larger, more structured female academies (also called seminaries), with formally trained teachers and rigorous curriculums. [For a detailed description of what the Tredwell girls would have experienced while students at Mrs. Okill’s, see Mary Knapp’s An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65 (2012)].

Mrs. Okill’s Tops the List

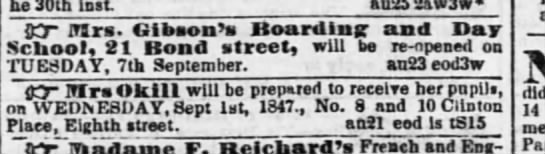

Competition for students must have been fierce among the women who ran the schools. Every year, beginning in late August and continuing through mid-September, advertisements for the schools, complete with names of notable individuals who were willing to provide endorsements, appeared in the daily newspapers. In New York As It Is (1833-1837), Mrs. Okill’s name is at the top of a list of 20 “Principal Female Seminaries” spread throughout the city. Ten years later, that number had grown significantly. In addition to Mrs. Okill’s, some of the other renowned female schools during this period, as mentioned by Catherine Elizabeth Havens (1839-1939), in her Diary of a Little Girl in Old New York (1919), were:

“Madame Chegaray’s, Madame Canda on Lafayette Place [both french schools], Mrs. Gibson on the east side of Union Square [more about her later], Miss Green’s on Fifth Avenue, just above Washington Square, and Spingler Institute on the west side of Union Square, just below Fifteenth Street.”

Influential Connections

When one considers that Mrs. Okill included the name of Reverend Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk (1791-1861) as a reference in her advertisements, it is understandable that Seabury Tredwell supported the school. Onderdonk was a relative of Seabury’s, and, as Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, a highly respected clergyman (until he wasn’t: stay tuned for a future post that will discuss his 1845 downfall). Other renowned citizens of New York, including Bishop Hobart, James Bleecker, and Peter A. Jay, also endorsed her school, which served to guarantee her cachet among the upper class.

Mrs. Okill Illegitimate … and a Divorcee?

Several circumstances of Mrs. Okill’s life, however, turn her pedigree on its head, notably her illegitimate birth and her divorce.

Mary Jay Okill was the daughter of Sir James Jay (1732-1815), oldest brother of John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Sir James, known primarily as the inventor of an invisible ink used by George Washington and his spies during the American Revolution, was also a physician and member of the New York State Senate; he was knighted by King George III for his fundraising efforts on behalf of Kings’ College.

According to an article in the Newsletter of the Bergen County Historical Society (2015-16), Sir James Jay never married Mary Jay’s mother, Anne Erwin (1750-1840), although they lived together in Springfield, New Jersey. A staunch advocate of a woman’s right to education, Miss Erwin refused to “honor and obey” Sir James, and therefore no marriage took place.

Mary Jay married John Okill, a merchant, on August 13, 1807, at Saint John’s Church on Varick Street. City Directories indicate that from 1807 through 1814, the couple lived with her father at various addresses on Greenwich Street and White Street. After Sir James’ death in 1815, neither Mary nor John Okill appear in the directories until 1819, when John Okill is listed as a broker on Wall Street. This entry remains unchanged until 1823, when he disappears entirely from the directories. The date and place of his death could not be determined.

In his will, probated in 1815, Sir James Jay stipulated that his daughter Mary’s inheritance, which included nearly 1,000 acres of land in what is now Closter, New Jersey, be put in trust “free of any control of her present husband, John O’Kill [sic].” According to the aforementioned article, Mary Okill divorced her husband in order to claim her inheritance. To earn a living, and perhaps influenced by her mother’s feminist beliefs, she opened a school for young ladies. Mary Okill is first listed in the 1823-4 City Directory as the proprietor of a “boarding school,” located at 43 Barclay Street. She remained at this location until 1838, when she moved to 8-10 Clinton Place (now 8th Street). She maintained her school until her death in 1859. Her establishment was always known as Mrs. Okill’s Academy.

What a Woman!

It is remarkable that, despite the social stigma associated with illegitimacy and divorce during the 19th century, Mary Okill was able to achieve such renown, especially among the privileged class, who valued family pedigree above all else. One wonders what shielded her from disgrace? Did her wealthy patrons know of her past, and decide to simply look the other way, due to the reputation of her uncle, John Jay? Or did she somehow manage to keep her background and divorce hidden from public scrutiny? In whatever manner she managed to maintain her reputation, her school was continuously celebrated as being run by “a lady of distinction,” and was undoubtedly a huge financial success. In an article in the New York Daily Herald (January 11, 1845), Mrs. Mary Okill is one of only a handful of women included in a list of the “wealthiest citizens” of New York City, with a net worth of $150,000. She joined such wealthy men as Adam Tredwell, Seabury’s brother, whose net worth was listed at $200,000.

The Tredwell family had an indirect connection to John Jay, which may have been a factor in their loyalty to Mary Okill. Reverend Samuel Nichols, Elizabeth Tredwell’s father-in-law, who married Elizabeth and Effingham in 1845, pronounced the eulogy at the Chief Justice’s funeral in 1829. Additionally, one of Effingham’s brothers, John Jay Nichols, was his namesake.

Co-Ed for the Children

Although it was known primarily as a female school, Mrs. Okill’s Academy also welcomed very young boys as students. Julia Lawrence Hasbrouck (1809-1873), who lived on Greenwich Street, enrolled her six-year-old son Louis and her five-year-old daughter Julia in Mrs. Okill’s Academy in 1843. She wrote her positive impressions of the school in her diary on November 30, 1843:

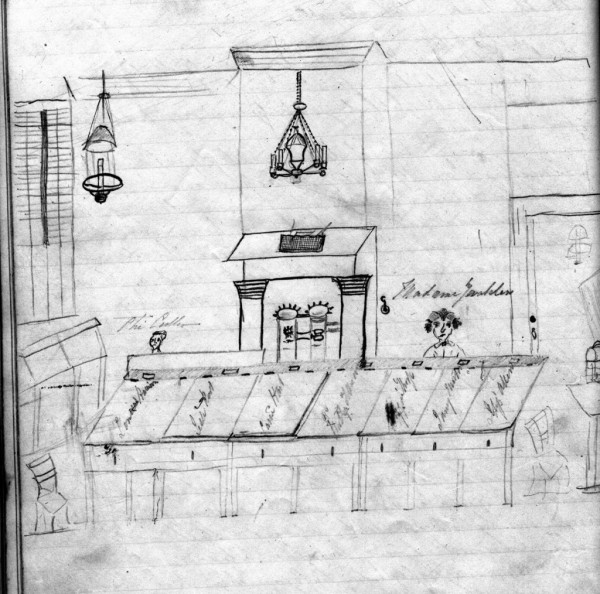

“The room was neat, comfortable, and well arranged. The little boys all looking happy, and merry. We went from there, to the little girls room, where I was equally pleased. The little creatures are not pinned down to their seats like prisoners, pale, and wearied; but were skipping around, combining study and amusement, the only safe method of instructing children.”

Although young Julia Hasbrouck attended Mrs. Okill’s at least through 1850, her brother Louis eventually joined another brother at an all-boys school. It is possible, then, that the Tredwell girls (and perhaps boys) attended Mrs. Okill’s from a much earlier age than was previously assumed.

Notable Students

In addition to the Tredwells, Mrs. Okill’s school attracted other families that made up the glitterati of New York society.

One of Mrs. Okill’s students was Eliza Hamilton Schuyler (1811-1863), the granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton. In 1825, when she was a 14-year-old student, Eliza was given a “prize book” from Mrs. Okill. In the Hamilton-Schuyler Family Papers at the University of Michigan, there are references to “Miss Okill’s ‘Testimonials’ for Eliza on that dainty embossed note paper …” and “While Eliza Hamilton was at Mrs. Okill’s School winning her encomiums …”

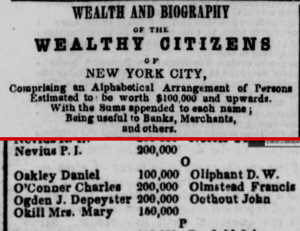

Another was Isabella Stewart (1840-1924), the daughter of a wealthy merchant, who would later marry John Lowell Gardner and become a famous art collector and philanthropist. From ages 5 to 15, while living with her family at 10 University Place, Isabella attended Mrs. Okill’s Academy. In 1855 she was awarded a Certificate of Excellence by Mrs. Okill, in return for a commitment to “remain till the close of school to receive it.” One year later, Isabella embarked on the Grand Tour of Europe with her parents and was enrolled in a French school to finish her education.

After Mary Okill’s death in 1859, the school closed, but her widowed daughter, Jane Swift, who had been a teacher at the school, continued to reside there. By May 1860, when the family moved to West Point, New York, the “very valuable property” on Clinton Place was up for sale. Like Mrs. Okill herself, the buildings were considered to be “of a superior character.”

Gertrude Tredwell, the Transfer Student

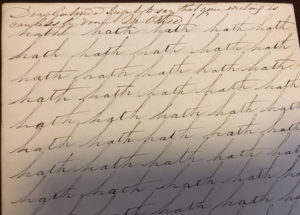

Among the copybooks belonging to the Tredwell girls in the Merchant’s House Museum archives, several belonged to Gertrude Tredwell. One, dated from December 16,1853, through February 13, 1854, (when Gertrude was 13 years old), indicates that Gertrude attended Mrs. Okill’s School, for at the end of a composition, a withering comment appears, written by the headmistress herself:

“Dear Gertrude, I regret to say that your writing is carelessly done. M. Okill”

Other copybooks of Gertrude’s, which date to 1858, do not contain any teacher’s notes. The Museum’s copy of Seabury Tredwell’s ledger book includes entries for payment of bills for “Gertrude’s tuition at Mrs. Gibson’s,” dating from 1855 and 1858 (tuition at the private academies averaged approximately $70 per year). We don’t know the reason for Gertrude’s departure from Mrs. Okill’s School. Whatever the reason for the transfer, Gertrude finished her education at the age of 18, under the tutelage of Mrs. Gibson.

Mrs. Gibson

In 1832, nearly ten years after Mrs. Okill opened her female academy, Mrs. Agnes Mason Gibson (1787-1872), from Edinburgh, Scotland, established her own school, assisted by three of her daughters. Originally located on Broome Street and operating as a day school, it was advertised on April 10, 1832, in the Evening Post:

“The Misses Gibson, having been educated under the first masters, are prepared to give instruction in all the branches of a useful and ornamental female education. Pupils will be received for French, Italian, Music, or Drawing, who may not wish to enter for other branches. Instructions upon the pianoforte and guitar will also be given in private homes. [Guitar instruction was not unusual. Christian Frederick Martin, the famous guitar maker who established his shop in New York City in 1833, sold several guitars to Mrs. Okill]. A class for conversation and composition in French will be opened on Saturdays, for young ladies who have made proficiency in the language.”

A Resounding Success

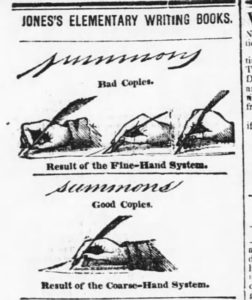

Two months later, Mrs. Gibson “expanded her plan” to include boarding students. Within a few years, her school achieved a remarkable degree of popularity; Mrs. Gibson became an influential educator in New York City. Manufacturers of school supplies sought her out for endorsements. In September 1838, an advertisement in the Evening Post featured Mrs. Gibson’s endorsement of Jones’s Elementary Writing Books. Mrs. Gibson stressed the importance of having children instructed in “large hand exercises:”

“I attribute the defects in the hand writing of young ladies to injudicious teaching in giving fine-hand exercises to write, before any foundation or command of the pen is acquired in large characters.”

“An Excellent Seminary”

As the school expanded it relocated several times, from Broome Street to Broadway to 21 Bond Street (just two blocks from the Merchant’s House), where in 1845, Mrs. Gibson gave an exhibition of her students’ work, which was lauded in the New-York Tribune. The school was referred to as “an excellent seminary – one of the best in the city for the instruction of young ladies.” The article goes on to say:

“We were particularly struck with the taste and judgment displayed in the elocutionary exercises. The French dialogues were given in a sprightly and graceful manner, and the vocal music was charming. We traced throughout the evening the workings of an intelligent, kindly, and well sustained course of instruction.”

The New York Post also covered Mrs. Gibson’s May Day Festival in May 1849:

“Of note were the performances of charades, in which the ingenuity and invention of the youthful scholars were exhibited. Many of the former pupils were present. It is charming thus to see wisdom’s ways made ways of pleasantness.”

The Dear Scottish Daughters

One of Mrs. Gibson’s students was Julia Cullen Bryant (1831-1907), daughter of poet and New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), who attended the school in 1844 at age 13. The family must have formed a strong attachment to Mrs. Gibson and her daughters, for William Bryant maintained a correspondence with his daughter’s teachers, Christianna Gibson in particular, until his death.

The Final Move

In 1851, Mrs. Gibson moved again, from 21 Bond Street to larger quarters at 38 Union Place, to accommodate her growing enrollment. Gertrude attended the school at this location, which was a short walk from her home on Fourth Street. The school operated at this location at least until 1861; eventually, Mrs. Gibson returned to Scotland with her daughters, where she died in 1872.

“An Annoyance and a Pleasure”

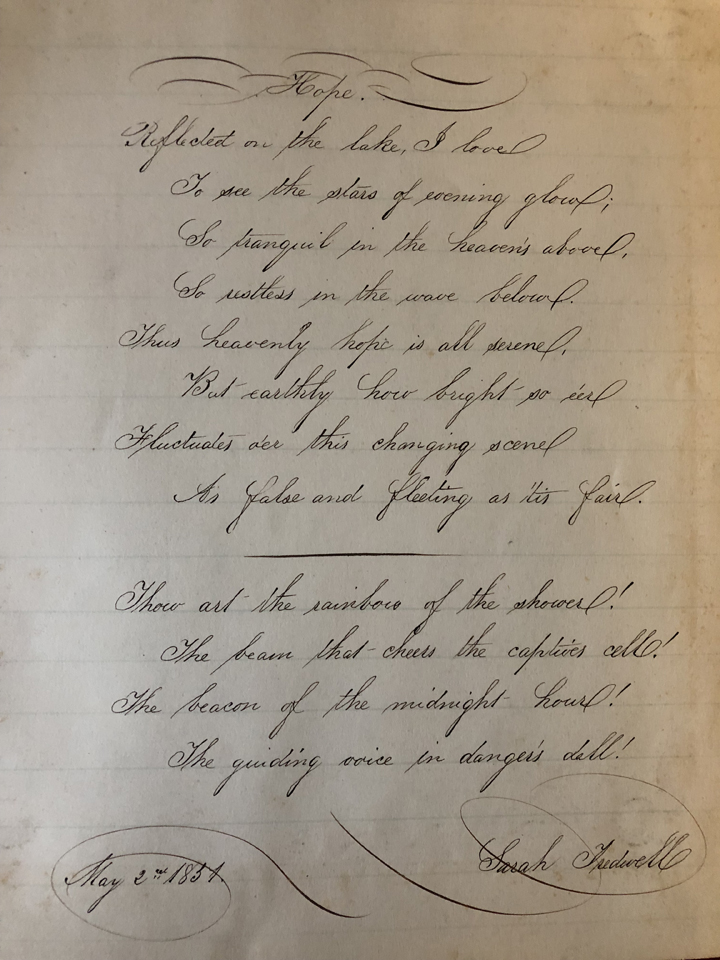

Despite the number of filled copybooks belonging to the Tredwell girls, all but one lacked any clues about the young women’s sentiments toward their schools. Only 18-year-old Sarah was brave enough to venture an opinion about her school years and the education she received. In a composition entitled “To a Dear Friend,” dated May 18, 1853, she expressed her ambivalence about her experiences and the end of her school days:

“Some say our school days are the most happy. I believe it to be true though there are certainly many things pertaining to school which are of a very perplexing nature. I will leave school the first of July, when I am to leave forever that place which I have frequented so many years and which has been to me both an annoyance and a pleasure. To those to whom I have grown and with whom I have shared the troubles of a school day life and to whom I must ever feel attached I must bid adieu but I hope not forever.”

Sources:

- Brown, Henry Collins. Valentine’s Manuel of Old New York, new series, no. 2. New York: Valentine Co., 1917.

- Bryant, William Cullen and Thomas G. Voss. The Letters of William Cullen Bryant: Volume IV, 1858-1864. New York: Fordham University Press, 1993.

- Christian Journal, and Literary Register, Volume 7-8, May, 1823. https://books.google.com. Accessed 9/9/18.

- Colony Club. Catalogue Exhibition “Old New York” Relics Documents and Souvenirs. New York: Colony Club, 1917.

- Evening Post. 25 August, 1824, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/5/18.

- Evening Post. 10 April, 1832, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 13 June, 1832, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 10 September, 1833, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- Evening Post. 22 August, 1834, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 13 January 1838, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- Evening Post. 1 September, 1838, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 8/24/18.

- Evening Post. 30 August, 1847, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Evening Post. 3 May, 1849, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Evening Post. 14 April, 1851, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Gura, Peter F. C.F. Martin & His Guitars, 1796-1873. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Hamilton-Schuyler Family Papers 1820-1924, William L. Clements Library Manuscript Division, University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu. Email 9/6/18.

-

Hayley, Ann, Robert Campbell et al. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: Daring by Design. New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2014.

- Knapp, Mary L. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City, 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- Leslie’s History of the Greater New York. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York register, and city directory. New York: David Longworth, [multiple years]. Reference, New York Historical Society.

- Madigan, Jennifer C. “The Education of Girls and Women in the United States: A Historical Perspective.” Advances in Gender and Education, 1 (2009), 11-13. www.mcrcad.org. Accessed 9/2/18.

- Manhattan, New York City, New York Directory: 1829-1830;1839-1840. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- Merchants House Museum Archives. Seabury Tredwell’s Ledger Book [copy], 1855-1865.

- Merchant’s House Museum Archives. Composition Book of Sarah Tredwell, May 18, 1853. 2002.4601.89.

- Merchants House Museum Archives. Penmanship book of Gertrude Tredwell, Dec. 16th, 1853 – Feb. 13th, 1854. 2002.4602.29.

- New York County, New York, Wills and Probates, 1658-1880. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- New York Evening Post. 22 Dec 1859. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- New York Evening Post. 27 June 1839. www.ancestry.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- New York Daily Herald. 11 January 1845, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- New York Daily Herald. 26 February, 1856, p. 5. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- New York Herald. 9 August, 1922, p. 11. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/22/18.

- New York Times. 20 September, 1859, p. 6. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/5/18.

- New York Times. 15 May, 1860, p. 6. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 6/6/18.

- New-York Tribune. 30 December, 1845, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 9/8/18.

- Stessin, Susan. The Diaries of Julia Lawrence Hasbrouck. www.frommypenandpower.wordpress.com. Accessed 8/22/18.

- Williams, Edwin, ed. New York As It Is, [1833-1837]. New York: J. Disturnell, 1833-1837.

- Wilson, James Grant, ed. The Memorial History of the City of New-York, Vol. III. New York: New-York History Company, 1893. https://books.google.com. Accessed 9/5/18.

- Wright, Kevin. “Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Tenafly.” In Bergen’s Attic: Newsletter of the Bergen County Historical Society. Fall/Winter, 2015-2016, p. 7-14. www.bergencountyhistory.org. Accessed 9/11/18.

Romance and Sweet Dreams: Mid-19th Century Courtship

by Ann Haddad

.

Valentines for an Eligible Lady

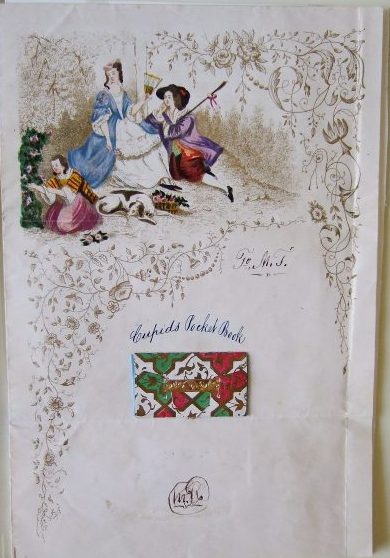

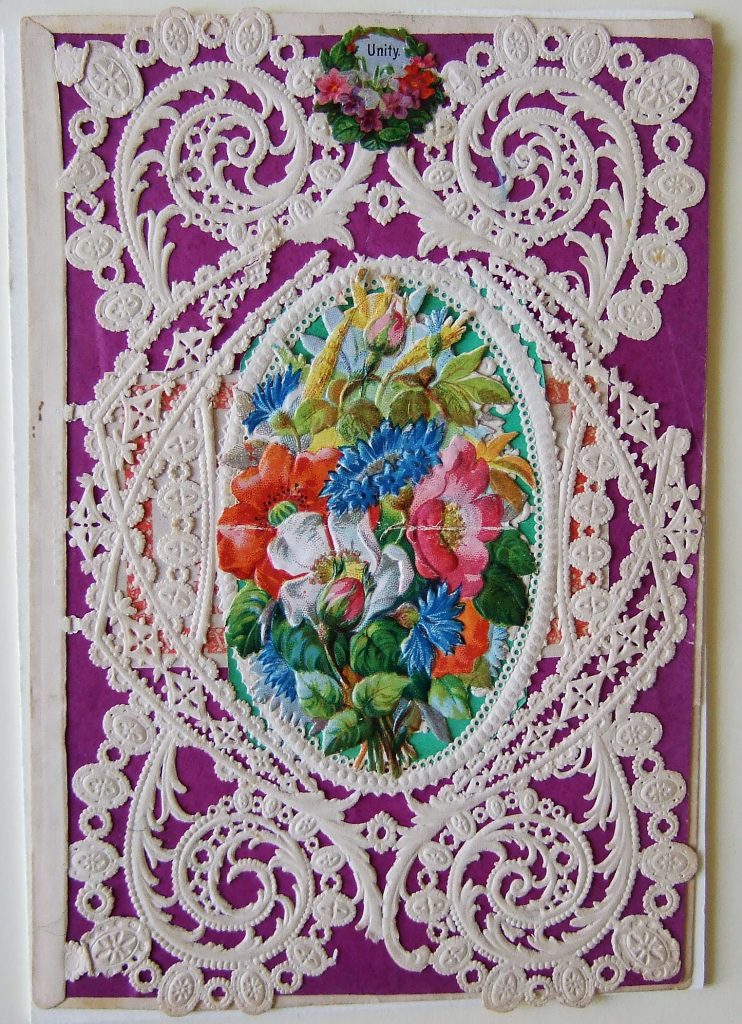

Valentine’s Day has been celebrated for centuries, but only became entrenched in American culture in the early 1840s, with the rise in popularity of commercially produced paper valentine cards. Made of delicately embossed and perforated lace papers, valentines became the fashionable way to convey romantic interest and to freely express the desire for romantic love.

The lovely Elizabeth Tredwell, eldest daughter of Seabury and Eliza, no doubt received her share of valentines from young men of her class. She was pretty and accomplished, and would certainly have been considered an eligible young lady. The Tredwell Archives contain several charming valentines; however, the senders and recipients are unknown.

On April 9, 1845, Elizabeth married Effingham Nichols (see our April 2017 blog post, “Days of Sorrow, Days of Rejoicing: The Marriage of Elizabeth Tredwell and Effingham Nichols”). We do not know when and how Elizabeth and Effingham met, nor are we aware of the length of their courtship. Based on the many strict codes of etiquette that governed courtship, however, we can assume theirs followed a dictated course.

.

.

.

Romantic Love

In the mid-19th century, romantic love was viewed as the solid rock upon which a healthy marriage was built; according to Karen Lystra, author of Searching the Heart (1989), it was only within the sacred state of marriage that one’s “ideal self” could be revealed. Courtship, therefore, was respected as a special time in the lives of a young couple. This period, after introductions and before a formal engagement, served to intensify the feelings of romantic love; to insure that the bond formed between a couple was true; to guide one in learning the real character of the other; and to ensure that their attraction was based on mutual respect and admiration. In Theocritus’ The Dictionary of Love (1858), it is defined as the period that is “all romance, excitement, hope, desire, expectation, and sweet dreams.”

Before Courtship: Under Mama’s Watchful Eyes

The time for a young woman to enter society and assume her role as a marriageable woman was determined by her parents; it depended not on her age, but on her level of maturity. A woman was also expected to have completed her education, or “finishing,” typically between the ages of 16 and 18, before entering society. Elizabeth most likely went “into company” (or “came out,” as it was later called) sometime around the age of 20.

Courting before this age was highly frowned upon. After completing her schooling, a daughter remained at home (which was viewed as a woman’s empire), under the watchful eyes of her mother. Here she learned domestic arts; assisted with rearing her younger siblings; and was instructed in the rules of manners and civility, which were highly valued in society. A young lady was chaperoned at public entertainments, such as theatre or dances, by her parents, brothers, or an intimate family friend. (Once she became formally engaged, her lover became her “legitimate protector and companion.”) She was expected to rebuff any male attention, and maintain a polite disinterest in courtship. Mrs. John Farrar, in A Young Lady’s Friend (1837), writes,

“The less your mind dwells upon lovers and matrimony, the more agreeable and profitable will be your intercourse with gentlemen. Regard men as intellectual beings who have access to certain sources of knowledge to which you are denied.”

Elizabeth also received guidance from her mother (likely culled from popular advice books such as Lydia Maria Child’s The Frugal Housewife (1829); Godey’s Lady’s Book; and etiquette and conduct manuals) about acceptable behaviors that reflect what Mrs. John Farrar called “delicacy and refinement” when in the company of young men. Never let a man hold your hand; decline his offer of assistance with getting in and out of carriages; never squeeze into a tight space with a gentleman; never speak of your private affairs or feelings; always have a friend present for carriage rides; never borrow money from a man; avoid gossip. Mrs. Farrer stressed:

“Your whole deportment should give the idea that your person, your voice, and your mind are entirely under your own control. Self-possession is the first requisite to good manners.”

Above all, a young lady was never to make obvious public plays for the attention of a young man, or insinuate that she wanted an invitation from him. According to T.S. Arthur, author of Advice to Young Ladies (1847), such inappropriateness indicated “an outrageous want of all decent respect for herself.”

Money and Religion

Aside from the usual parental concerns associated with finding a suitable partner for their daughter, Seabury and Eliza Tredwell had another reason to be extremely careful when vetting young men who were interested in courting Elizabeth: the family’s enormous wealth. Guarding against any unprincipled suitor who viewed a fortune as indispensable when choosing a wife was no doubt of utmost importance. They therefore sought to find a husband for Elizabeth whose own wealth was equal to or greater than her own. Similarity of religion was also considered to be a requisite; whoever sought and won Elizabeth’s hand had to be of the Episcopal faith (see our February 2017 blog post, “The Man That Got Away,” for a discussion of the aborted romance of Elizabeth’s youngest sister, Gertrude, and Luis Walton).

A Formal Introduction

A gentleman did not consider courting a woman unless he had been formally introduced to her. (Men were not without their etiquette manuals: Lord Chesterfield’s Advice to His Son on Men and Manners, first published in 1774, was the popular source.) Effingham may have been introduced to Elizabeth through her father or one of her uncles, or through a respected friend of the family. For those without known connections, it was the gentleman’s task to respectfully make her acquaintance. Upon noticing a woman at a dance, for example, he first learned her name by making discreet inquiries, and then, through his societal connections, asked for an introduction. As the couple became acquainted through conversation, the gentleman ascertained the woman’s level of interest, and whether any further attentions were welcome.

Dear Mr. Tredwell

If he perceived that she was not averse, and he was confident that his position in life and circumstances were sufficient to allow him to proceed, a gentleman took the next step — writing to the woman’s father to ask permission to pay a visit to their home. In this important communication, he stated his position and prospects, and mentioned his family. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony (1852) cautioned the suitor against any smugness or over-confidence at this stage:

“Never think you are doing the family a favor. A man must convey delicate respect towards the parents, to prove himself worthy of the treasure of which he is about to deprive them.”

The following portion of a sample letter from The Art of Good Behavior (1845) may be similar to one sent to Seabury Tredwell from Effingham Nichols, when he desired to begin courting Elizabeth:

“The subject upon which I presume to address you is one so near to my heart, and so connected with my prospects of happiness in this life, that I find it difficult to summon resolution for the task; but sir, I have dared to entertain so high an opinion of your goodness, that I am emboldened to write to you with candor, to solicit the greatest favor it is in your power to bestow.”

Emily Thornwell, in The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility (1856), defined the proper look of a letter from a potential suitor to a young woman’s father:

“Observe that letters of introduction are never sealed by well-bred people. Every letter to a superior ought to be folded in an envelope. It shows a want of respect to seal with a wafer; we must use sealing wax; men usually select red.”

Once permission was obtained from the father, the young lady in question then extended a letter to the gentleman, inviting him to pay a call. She avoided displaying any excessive interest in him, however. Thornwell emphasized the importance of restraint:

“You should not remark to a gentleman, ‘I am very happy to make your acquaintance;’ because it should be considered a favor for him to be presented to you, therefore the remark should come rather from him.”

The Trial Period

As soon as the father established that a young gentlemen was suitable company for his daughter (accomplished through inquiries among his set as to the family and status of the suitor), courtship commenced. In the young lady’s front parlor, with a chaperone present, a courting couple engaged in allowed activities including singing, talking, piano playing, and parlor games with other guests. Supervised carriage rides and outdoor excursions to dances, picnics, dinners, and concerts were also permitted. During this time, the couple observed one another’s habits and conduct for evidence of good moral character and virtuous principles, and hence suitability.

A woman considered positive traits, such as a man’s ability to speak with ease, respect, and courtesy to all; a neat appearance; excellent manners and deference to all women; and his readiness to honor and defend the opposite sex. Among the negative qualities that put a woman on her guard, as noted in The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony, were:

“Keeps irregular hours

His studies do not form the subject of his conversation, as bearing on his future prospects

Shows disrespect for any age

Laughs at things sacred

Absents himself from regular attendance at church

Shows an inclination to expensive pleasures, or to low and vulgar amusements

Betrays a desire for enjoyments beyond his means or reach

Makes his dress a study

Betrays a continuous frivolity of mind.”

Etiquette manuals were replete with warnings to young ladies to beware being dazzled by “morally depraved” men or, as stated in Advice to Young Ladies:

“A young lady should be careful that brilliant qualities of mind, a cultivated taste, and superior conversational powers, do not overcome her virtuous repugnance to base principles and a depraved life.”

The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony also provided guidelines for gentlemen as they waded into the murky waters of courtship. A woman who was kind, patient, benevolent, peaceful, and charitable; and who enjoyed home-centered pleasures, was worth pursuing. But a gentleman should “retire speedily but politely” from a woman with any of the following traits:

“Has the heartless buzzing of a flirt

Gives smiles to all and a heart to none

An uneven temper

Is fond of dress, and eager for admiration

Is ecstatic in trifles and nonsense, and frivolity

Is weak in her duties

Is petulant, saucy, or insolent

If the holiness of religion does not hover like a sanctifying dove ever over her head

Is prideful, boasting, vane, sharp rather than quiet

Gaudy”

When choosing to cast his eye upon a young lady with views toward matrimony, a gentleman needed to be mindful of the following:

“You do not catch us by mere beauteous look,

Tis but the bait, floating without the hook.”

Despite all these dire warnings, the author ended on an uplifting note:

“In nine out of ten cases it will be found that some demonstration of gentleness, benevolence, devotion, or self-sacrifice will invariably have been the foundation and first cause of serious thoughts of matrimony.”

No Gifts, Please

Another rule of courtship prohibited a young lady from accepting presents from a gentleman, prior to his having made a distinct proposal of marriage. It was considered improper and unbecoming, and implied an obligation on her part. Should the gentleman insist on her accepting a gift, she was to acknowledge its receipt in the presence of her parents, thereby removing any trace of impropriety. Any gifts received anonymously were put away and never mentioned. According to T.S. Arthur’s Advice to Young Ladies, flowers, fruit, and candy were the only acceptable presents from a young man to a young lady prior to their engagement, because:

“their perishable nature exempts them from the ban put upon more enduring memorials.”

Love Letters: “The Sweetest Things”

With all the restrictions placed upon young lovers during their courtship, letter writing became the allowed means by which they could express their feelings, continue the process of getting to know one another, and hopefully, fall in love. In the mid-19th century, suitors had at their disposal numerous letter-writing manuals that offered sample letters for every occasion, including expressions of romantic love and marriage proposals. In The Dictionary of Love (1858), love letters were referred to as, “among the sweetest things which the whole career of love allows.” The author of The Art of Good Behavior wrote: “The delicate and interesting preliminaries of marriage are oftener settled by the pen, than in any other manner.”

Love letters were considered sacred and sincere testaments to a couple’s love; such intimate correspondence was regarded with respect and a deep sense of privacy. A family member would never open a daughter’s or sister’s love letter; upon receiving it she retired to her room to read its contents in private.

It comes as no surprise to learn that rules governed the writing implements, paper, and even stamps, for love letters. The Art of Good Behavior insists:

“For a love letter good paper is indispensable. When it can be procured, that of a costly quality, gold-edged, perfumed, or ornamented in the French style, may be properly used. The letter should be carefully enveloped, and nicely sealed with a fancy wafer – or what is better, plain or fancy sealing wax. The whole affair should be as neat and elegant as possible.”

We have no surviving love letters between Effingham and Elizabeth. Perhaps one might have been similar to the following, from the Butler-Laing Family Papers (NYHS), written in 1861 by Frank Butler to his cousin Mary:

“My dear Cousin if you could only realize how deep an attachment I have found for you, and how sincerely and fondly I have learned to love you, even from the very first hour of our meeting, you might then imagine the thought of being so wholly separated from you, for how long a time God only knows, can be attended with painful feelings only.

Goodbye Mary, and may God bless you and the other members of the happy family with which you are connected. And may you sometimes, in your nightly visions think of one who holds you in highest admiration and unlimited affection.

Devotedly your cousin,

Frank Butler”

Another, unsigned and undated, from the Emily Hosack Rodgers Collection (NYHS), indicated the freedom a gentleman felt in writing to his love interest:

“If you love me, I will seek only to enfold your whole existence within the arms of a true and devoted love. With the true wisdom of an affectionate heart I will only seek, will only desire to find my own happiness in yours.”

A Valentine’s Day Poem

The Obituary Record of Yale University (1902) mentioned that Effingham Nichols wrote poetry and prose. Perhaps he sent a valentine poem to Elizabeth during their courtship. It may have been similar to this one, “Friendship Offering” (NYHS), written in 1832 to Anna Brooks:

“If though thinkest, Anna

That I shall complement thee now,

And say how well you play on the piano,

And praise the brightness of thy brow;

Or tell thee that thy voice is sweet,

Or that thou hast a lovely face,

Or snowy hands, or pretty feet,

Or complement one single grace,

That throws its glory o’er thy manner,

Or even praise those eyes of thine!

Thou art indeed mistaken, Anna;

Although in every Valentine,

I know thou hast a right to think

Such praise would be given to thee;

But thou! oh, thou couldst never drink,

Deep of the cup of flattery:

For in the depths of thy young mind,

Life’s holiest treasures are enshrined.

Learning and wit, and beauty bright,

And virtue – charms that alone delight

The soul – Yes! All these blessed gifts are thine.”

Our next blog post will address the rituals surrounding marriage proposals and engagement. Happy Valentine’s Day!

Sources:

- Anonymous. The Art of Good Behavior, and Letter Writer, on Love, Courtship, and Marriage: A Complete Guide. New York: Huestis & Cozans, 1845. Main Collection, New-York Historical Society.

- Anonymous. The Etiquette of Courtship and Matrimony. London: David Bogue, 1852. books.google.com. Accessed 1/18/18.

- Arthur, T[imothy]S[hay]. Advice to Young Ladies on Their Duties and Conduct in Life. Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1847. babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 1/16/18.

- Brooks, Anna. Valentine’s Day Poem, 1832. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Butler-Laing Family Papers, 1818-1892. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Emily Hosack Rodgers Collection, 1848-1888. Manuscripts Division, New-York Historical Society.

- Farrar, Mrs. John. A Young Lady’s Friend. Boston: American Stationers’ Company, 1838. internetarchive.org. Accessed 1/23/18.

- Halttunen, Karen. Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

- Knapp, Mary L. An Old Merchant’s House: Life at Home in New York City 1835-65. New York: Girandole Books, 2012.

- Lystra, Karen. Searching the Heart: Women, Men, and Romantic Love in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Rothman, Ellen K. Hands and Hearts: A History of Courtship in America. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1984.

- Theocritus, Junior [pseud.]. Dictionary of Love. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1858. internetarchive.org. Accessed 1/22/18.

- Thornwell, Emily. The Lady’s Guide to Perfect Gentility: In Manners, Dress, and Conversation. New York: Derby & Jackson, 1856. internetarchive.org. Accessed 1/17/18.

- Valentines. American Antiquarian Society. americanantiquarian.org. Accessed 1/24/18.

- Yale University. Obituary Records of the Graduates of Yale University Deceased from June,1890 – June, 1900. New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1902, p. 672.

Nature for Ladies: The Victorian Art of Flower & Seaweed Pressing

by Ann Haddad

Escaping the Summer Heat

As city dwellers do today, many 19th century New Yorkers desired to escape the wretched summer heat and humidity by retreating to the seaside or country for the fresh air and cooler temperatures. For the Tredwells, that usually meant traveling to Rumson, New Jersey, where they relaxed at their 850-acre farm near the ocean. But the summer of 1865 must have been a difficult time for the family. Their grief over the loss of Seabury Tredwell in March surely was still fresh, and they were only four months into their one-year mourning period.

A Change of Scenery

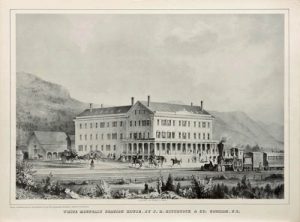

Perhaps that is why, in July 1865, 24-year-old Gertrude, no doubt along with other family members, chose a new destination. Instead of, or in addition to, summering in Rumson, they ventured to both the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and Northampton, Massachusetts. Popular tourist attractions in the mid-to-late 19th century, the White Mountains in particular drew many celebrated visitors, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, painter Thomas Cole, and Mary Todd Lincoln who, along with her son Robert, journeyed there in 1863. Northampton was called the “loveliest village of America” by The New York Times in 1865.

A Long Journey

Gertrude and her entourage could have taken two routes to reach the White Mountains. One was to hire a carriage to bring them to Peck Slip on the East River in lower Manhattan. There they would board the 3:15 p.m. steamer and travel to New Haven, Connecticut, then switch to the New Haven Railroad and later, a stagecoach, which would bring them to the White Mountains. Or, the carriage driver may have been directed to the New Haven Railroad depot at Fourth Avenue and 27th Street, where the group would board the 12:15 p.m. train and travel exclusively by rail. Either way, the day-long journey necessitated an overnight lodging, usually in Springfield, Massachusetts.

After spending a week or two enjoying the beauty of nature in the White Mountains, Gertrude and her fellow travelers made the return trip by rail, stopping for a time in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she and her party ascended Mt. Holyoke. Here she enjoyed another idyllic mountain scene, and the quiet beauty of the Connecticut River Valley, before returning home.

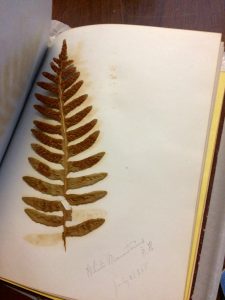

A Bounty in the Archives

How do we know for certain that Gertrude visited the White Mountains and Northampton in July 1865? The Tredwell Archives at the Merchant’s House Museum contain a large collection of pressed flowers and seaweed, both mounted in scrapbooks and on loose leaves, dating from 1858 to 1876. The scrapbooks bear Gertrude’s name and she made notations on several of the pages indicating where the specimens were obtained, such as “Mt. Holyoke,” “Northampton,” and “White Mountains.” They were dated either July 1865, or July 20, 1865.

- (Click images to enlarge.)

Mother-Daughter Time

We are not certain if all of the pressings in the extraordinary collection were made by Gertrude. Her sisters may also have enjoyed the hobby. But we do know that both scrapbooks of pressed flowers, ferns, and seaweed bear her name; and many individual pages bear the initials “E.T,” and “E.E.T.” This can only be Gertrude’s mother, Eliza Earle Tredwell. Perhaps Gertrude developed her obvious passion for the craft from her mother; it may have been an activity they pursued and delighted in together.

A Victorian Pastime

In the mid-19th century, flower pressing emerged as one of the most popular pastimes for Victorian middle and upper class women. With plenty of time on their hands, and no dearth of resources, they sought to explore their artistic side in unique ways. Wishing to be part of the skyrocketing craze for natural history at that time, yet restricted by virtue of their sex, many women found the art of identifying and collecting plant specimens to be a respectable way of examining the natural world, improving their scientific knowledge, and preserving the beauty around them. It became an acceptable way for women to merge the natural world with the domestic one; respect for nature was also viewed as a Christian road to God. A woman given to this pastime would pride herself on her “herbarium,” or collection of flora.

Women also pressed flowers for sentimental and romantic reasons. The flora pressed into a book or album served as a remembrance of a particular person or event; for Gertrude, her scrapbook also served in part as a travel log.

.

.

A Kindred Spirit

One well-known herbarium maker was the poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), who as a young girl pressed many specimens into a bound album, much like the ones created by Gertrude. In an 1845 letter to a friend, Emily wrote, “Have you made an herbarium yet? I hope you will if you have not, it would be such a treasure to you; most all the girls are making one.”

It is pleasant to imagine Gertrude and Emily (who lived only 10 miles away in Amherst) meeting on Mt. Holyoke as they pursued their shared passion!

How It Was Done

In order to maintain the freshness and vibrant color of the florals, Gertrude or Eliza purchased a wooden field press. Many stationers quickly caught on to the popularity of the hobby and rushed to stock presses and other needed supplies, such as paper and glue. For those who desired to learn the craft, popular magazines often published instructions, especially in the fall when the brilliant colors of the autumn foliage would inspire collecting.

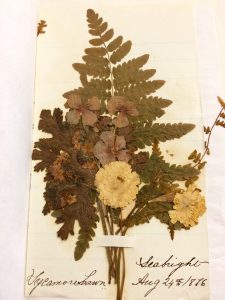

Picking the flowers late in the afternoon ensured that all the dew had dried. They were then placed between sheets of blotting paper and pressed with a crank or straps to tighten and flatten the specimen. Once dried, the flowers were glued, sewn, or attached onto paper (which was plentiful and inexpensive during the Industrial Revolution), silk, velvet, or other fabric. Gertrude kept hers in a scrapbook; framing under glass was also a popular way to exhibit one’s work. Or the flowers could be pressed between the pages of a beloved book or family Bible.

Many of the specimens in the Merchant’s House Museum collection are of delicate, intricately-patterned seaweed, probably gathered at the shore in New Jersey. Readily available, especially for women who spent summers at the seaside, seaweed emits a sticky, gelatinous substance when pressed, thereby eliminating the need for glue when mounting. The pungent smell subsided once the specimen was pressed. Seaweed presented an artistic and technical challenge (even for devotees such as Queen Victoria), for one had to work very carefully to avoid disrupting its complex structure. Added to that was the difficulty of wading into the water wearing heavy Victorian garb. The noted seaweed collector Margaret Gatty (1809-1873) recommended that “seaweeders” wear heavy men’s boots when wading: “Feel all the luxury of not having to be afraid of your boots.”

The collection also includes ferns gathered along the banks of the Shrewsbury River near to the family farm, as well as several specimens marked “Harlem,” reflecting the rural nature of that part of New York City in the mid-19th century.

Patience, Patience

One has to only glance at the Tredwells’ collection of pressed flora to realize the extraordinary precision, patience, and technical skill that was required to arrange the delicate specimens, especially the seaweed. Indeed, in a New York Times article from 1874, the reader is cautioned that seaweed pressing requires:

“… the greatest delicacy of touch and the most absolute attention. It would not be a bad idea to serve a preliminary apprenticeship at lace-making.”

Although they did not label their specimens, both Gertrude and Eliza created unique arrangements that are works of art. It must have taken hours to do such painstaking work; clearly both women loved exercising their artistic talents in this manner. Many of the flowers still retain their bright colors because they have had little exposure to light.

Mementos

It is uncertain if the trip to the White Mountains in July 1865 was the family’s first; they did make subsequent trips to the area, but none of the other pressings are marked as having been collected there. The latest specimen that bears Eliza’s name is dated August 24, 1876, and was collected from Seabright (another name for Rumson), when she was 79 years old! Eliza would die 6 years later, in 1882. We do not know how long Gertrude continued to enjoy the craft of flower pressing, or whether she derived joy from looking through the albums in later years. We like to think that they evoked sweet memories of happy days, and of her mother.

Sources:

- Farr, Judith. “Victorian Treasure: Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium.” February 19, 2014. Academy of American Poets. www.poets.org. (accessed 8/8/17).

- Giaimo, Cara. “The Forgotten Victorian Craze for Collecting Seaweed.” November 14, 2016. Atlas Obscura. www.atlasobscura.com. (accessed 8/8/17).

- “From Northampton. Beauties of the Scenery.” The New York Times, 01 Sep 1865, Pg. 1.

www.newspapers.com. (accessed 8/4/17). - Oatman-Stanford, Hunter. “When Housewives were Seduced by Seaweed.” Collector’s Weekly. November 7, 2013. www.collectorsweekly.com. (accessed 8/8/17).

- “Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains.” Museum of the White Mountains Online Exhibition. Plymouth State University. www.plymouth.edu. (accessed8/4/17).

- Richards, T. Addison. Appletons’ Companion Hand-Book of Travel. New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1862.

- “Seaweed Pressing.” The New York Times, 29 May, 1874, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. (accessed 8/4/17).

- Wallace, R. Stewart. “Turnpikes, Stage Coaches and the White Mountain Express: Transportation in the White Mountains.” wwwwhitemountainhistory.org/uploads/Turnpikes_enh.pdf. (accessed 8/4/17).

- Witemeyer, Karen. “Victorian Flower Pressing,” Petticoats and Pistols. April 30th, 2011. www.petticoatsandpistols.com. (accessed 8/8/17).

The Man That Got Away: Gertrude’s Lost Sweetheart

by Ann Haddad

An Abundance of Daughters

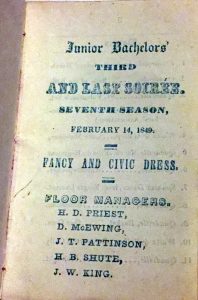

By anyone’s measure in antebellum New York City, the Tredwell daughters would have been viewed as highly desirable marriage prospects. As the children of Seabury Tredwell, a wealthy merchant with a fine home in the elite Bond Street neighborhood, they stood to inherit a portion of their father’s estimable worth. They counted among their social circle other members of the New York City upper class, and would have mingled with many eligible young men at the frequent soirées held at one another’s homes, or at other socially acceptable venues.

Party Girls

The Museum archives contain several items, including dance cards and playbills, that provide a glimpse of the Tredwell daughters’ social whirl. One is a silver Valentine’s Day dance card from the “Junior Bachelor’s Third and Last Soirée,” dated February 14, 1849. The lovely dresses in the Museum’s collection that belonged to the sisters indicate that they had the means and the sophisticated taste to keep up with fashion trends.

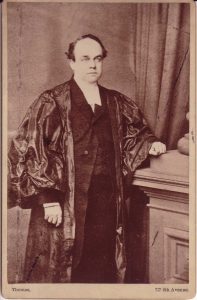

A Gentleman Caller

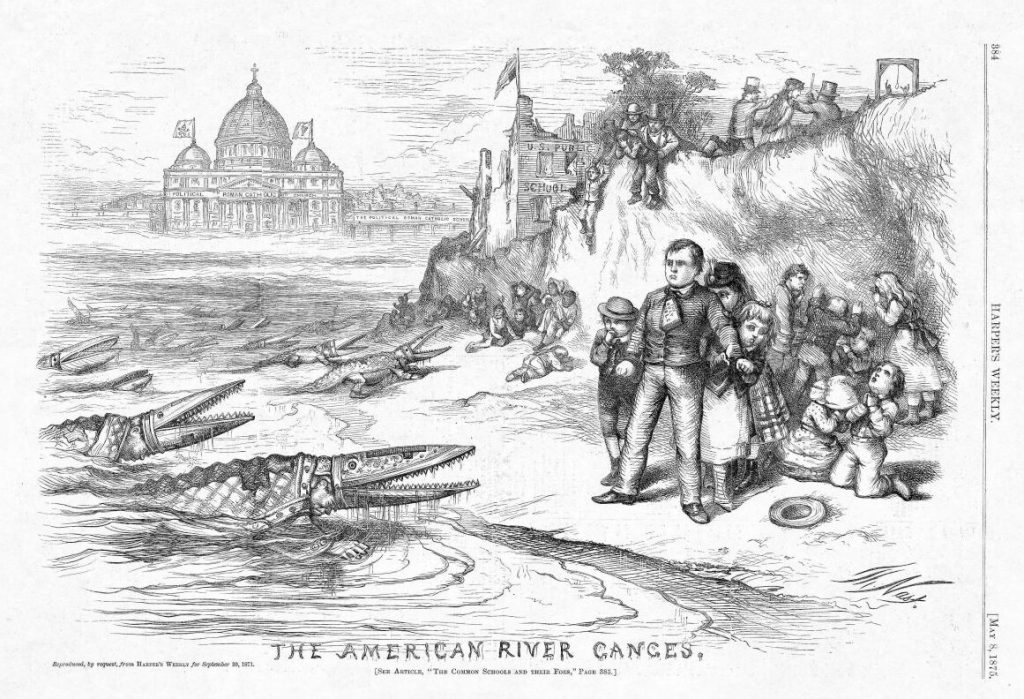

Gertrude Ellsworth Tredwell, born in 1840, was the youngest child of Seabury and Eliza. Family lore has it that when she was a young woman, Gertrude had a suitor whose name was Luis Walton. We don’t know if Luis ever had the opportunity to enter the Tredwells’ formal Greek Revival parlor to meet Gertrude’s father, and perhaps ask for her hand in marriage; however, we can be fairly certain the young man had three strikes against him. First, Luis’ father was a physician, from England. Physicians, especially those trained in England, were held in much lower esteem than they are today. Moreover, Seabury, a believer in homeopathy (see my blog post of October 18, 2016), might well have cringed at the idea of an allopath like Luis’s father becoming a member of his family. Second, Luis and his family were Roman Catholic. The Tredwell family came from a long line of staunch Episcopalians, and anti-Catholic prejudice ran deep in antebellum New York.

Finally, his mother was Irish; well, the Tredwell servants were Irish! The Irish were on the lowest rung of the social ladder; the contempt towards members of this large immigrant group was strenuous and prevalent. Surely, Luis could not expect to meet Seabury’s high standards of eligibility for Gertrude’s hand in marriage. And so, after his brief appearance on the Tredwell stage, Luis Walton vanished forever. Or did he?

A Liverpool Lad

Luis Puertas Richard Walton was born in Liverpool, England on November 18, 1840. The England census record of 1841 indicates that at the time of Luis’s birth, the family had a boarder named Luis Puertas, who was listed as a “cigar dealer from foreign parts.” This must have been Luis Walton’s namesake!

Luis’s father, Henry Christmas Walton, was a licensed physician and apothecary. His mother, Elizabeth, was from Ireland. In 1849, Luis was baptized Roman Catholic at the Church of St. Peter in Liverpool.

A Neighborhood Boy

Life must have been difficult for the Walton family, for in 1844 Dr. Henry Walton declared bankruptcy in London. This may be what compelled him to immigrate to New York City in 1850 with his wife and four children, when Luis was 10 years old. The family’s first identified residence was on 590 Houston Street, on the corner of Mercer Street, a short walk from the Tredwell home on East Fourth Street. From there they moved to West 10th Street. By 1860, the family was comfortably ensconced in their own home on 37 West 16th Street, with five servants in their employ, indicating that the family’s financial situation must have vastly improved. We don’t know if Seabury was aware of their good fortune, but the young man’s religious and cultural disadvantages most likely prevailed in Seabury’s consideration of him as a potential son-in-law.

On to Medical School

We can only guess that Gertrude and Luis, living in such close proximity to one another, met somewhere in the neighborhood through mutual friends. We don’t know if they saw each other once Seabury expressed his disapproval. Luis may have been discouraged, but he clearly wanted to make something of his life. He pursued an education at Columbia College (then at Madison Avenue and 49th Street), earning his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1861, and three years later a Masters of Arts degree from the same institution. In 1870, after a two year course of study, he received his M.D. from the prestigious Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons (then located at 4th Avenue and 23rd Street). His father was one of his preceptors during his medical training.

.

A Successful Medical Career

Luis became a successful physician in New York City. After medical school, he resided and practiced for several years on West 17th Street; he then lived at various residences in the West 30s, until his final move to 73 West 50th Street, where he lived and maintained a lucrative general practice until his death. No doubt he followed his well-off private patients as they moved further uptown. He was a member of the Medical Society of the County of New York (1888-1903), as well as the New York Clinical Society.

Friendship with Edward Livingston Trudeau

In addition to his private practice, Luis served as an Attending Physician at both the Northern Dispensary (at Christopher Street and Waverly Place), and the Demilt Dispensary (at Second Avenue and East 23rd Street), charitable institutions that provided care to the poor and destitute of New York City. One of his colleagues at Demilt, who co-taught a class on diseases of the chest, was public health pioneer Edward Livingston Trudeau (1848-1915). Trudeau, himself a victim of tuberculosis, would in 1885 establish a famous sanatorium for victims of the disease in Saranac Lake in the Adirondack Mountains and, several years later, the first laboratory in the United States dedicated to the study of tuberculosis. In his autobiography, Trudeau makes frequent mention of Luis Walton, and credits his friend with drawing his attention to the work of the German physician Dr. Hermann Brehmer in establishing the practice of open-air treatment for tuberculosis. On a more personal level, Trudeau reveals Walton’s frequent calls and assistance during his bouts of illness:

“Dr. Walton was the greatest comfort at that time, and assured me he would look after my wife and ‘those dreadful little Trudeau brats,’ and he certainly kept his word. Walton all through the summer made regular pilgrimages to Little Neck [where Trudeau’s family stayed while he was recuperating in the Adirondacks], and reported to me of their welfare, while assuring me what a nuisance it was to have to look after another man’s family.”

Oh, to Be in England

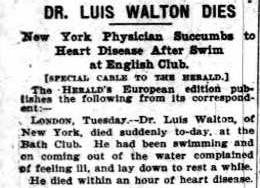

Luis clearly loved the country of his birth. An avid Anglophile, he was a member of the prestigious St. George’s Society of New York, a charitable organization that offered assistance to those born under the British flag. He also made frequent excursions to London, where he was a member of the elite Bath Club in Piccadilly. On September 8, 1903, after a swim at the Club, Luis died suddenly. He was 62 years old. His death was attributed to longstanding heart disease. He was buried at Kendal Green Cemetery in London. He left his estate to his surviving sister, Lucy Walton Mooney. The obituaries in professional journals that appeared at his death indicate that he was a highly esteemed physician, with a kindly manner and a deep compassion for his patients.

.

Lovers Apart?

We do not know the extent to which Gertrude and Luis maintained any relationship through the years. They must have corresponded with one another, for Gertrude referred to him in a letter to her nephew John T. Richards, dated November 18, 1924:

“You know Dr. Walton had “Angina Pectoris” but he lived for years with it – Strained himself climbing the Alps.”

Gertrude also kept in touch with at least one member of Luis’s family. The law firm hired by Gertrude and Julia to manage the estate of Sarah and Phebe Tredwell upon their deaths in 1906 and 1907 was Blandy, Mooney, and Shipman. The Mooney is Edmund Luis Mooney, a nephew of Luis Walton, who was with him in London at the time of his death. Coincidence? What do you think?

Assuming that Seabury’s disapproval of Luis is what precipitated the young man’s disappearance from Gertrude’s life, what kept the couple apart after Seabury’s death in 1865? Why did Gertrude never marry? Tradition has it that she vowed that if she couldn’t wed Luis, she would never marry. Perhaps her mother and older siblings were as much against the marriage as her father had been. Gertrude may have been reluctant to go against his wishes and the predominant Protestant culture of affluence and gentility in which she was raised. Or maybe the answer is simply that she never fell in love with any man after Luis. Whatever their reasons, there is one certainty: neither Gertrude, nor Luis, ever married.

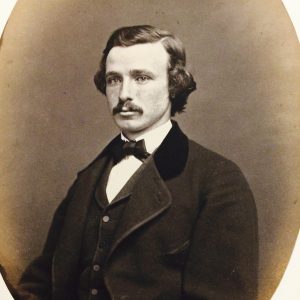

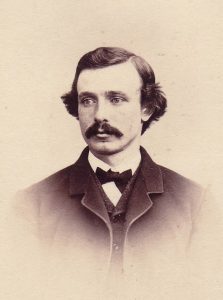

While researching Luis Walton, his 1861 graduate photograph was located in the Class Photograph Albums Collection at Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Museum staff recognized him from a previously unidentified photo in the collection (pictured above). We don’t know how the carte-de-visite of Luis came to be in the Tredwell home, but it remained there for the rest of Gertrude’s life. Valentine’s Day is the perfect occasion to celebrate the star-crossed love story of Gertrude and Luis!

Sources:

- ancestry.com England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975. Accessed 7/29/14.

- ancestry.com England Census, 1841. Accessed 7/31/14.

- ancestry.com New York, State Census, 1855. Accessed 7/29/14.

- ancestry.com United States Federal Census, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900. Accessed 7/31/14.

- ancestry.com U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989: 1902, 1903. Accessed 7/27/14.

- ancestry.com Directory of Deceased American Physicians, 1804-1929, JAMA Citation: 1903:41:736. Accessed 7/27/14.

- ancestry.com U.S. School Catalogues, 1765-1935: 1857-1861. Accessed 7/21/14.

- “Apothecaries Hall.” Lancet. Volume 1, p. 167. Accessed 7/21/14.

- “Bankrupts.” archive.thetablet.uk, pg. 8, 17 August, 1844. Accessed 7/21/14.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons. Catalogue of the Alumni, Officers, and Fellows 1807-1880, p. 122. Archives & Special Collections, A.C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons. Student Registers 1863-64 – 1878-79. Archives & Special Collections, A.C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons. Graduates of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Annual Catalog, 1870, p. 16. Archives & Special Collections, A.C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center.

- Columbia University. Class Photograph Albums Collection 1856-1902, UA#0131, Bib. ID 10278078, Box 79, 1861. Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Butler Library, Columbia University.

- Medical Directory of the City of New York. New York: Medical Society of the City of New York, 1887-1900.

- Medical Register of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, 1872, p.158, 159.

- New England Journal of Medicine. Volume 149, September 17th, 1903, p. 332.

- newspaperarchive.com. London Standard, Friday, September 11th, 1903, p.7.

- newspaperarchive.com. London Monitor and New Era. Friday, September 18th, 1903, p. 11.

- Records of the Northern Dispensary, 1827-1955. Series 1, Box 3. New York University Archives, Bobst Library, New York University.

- St. George’s Society. A History of St. George’s Society of New York from 1770 to 1913. New York, [St. George’s Society], 1913.

- Trudeau, Edward Livingston. An Autobiography. New York: Doubleday, Doran, and Company, 1915.

The New Woman

by Merchant's House Museum

Our thanks to guest blogger Esther Crain.

Esther Crain, a native New Yorker, is the author of 2016’s The Gilded Age in New York, 1870-1910 (Hachette) and the New-York Historical Society’s New York City in 3D in the Gilded Age (Black Dog & Leventhal) published in 2014. She is the founder and editor behind Ephemeral New York, a website that chronicles the city’s past, which was been featured in numerous publications, including the New York Times, New York Daily News, and New York Post.

Introducing the New Woman

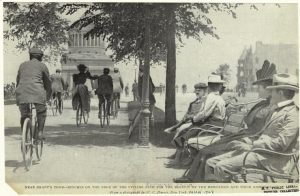

They began appearing in the 1890s: young women, their hair pinned back or piled in loose waves under elaborate hats, striding confidently down Broadway and Fifth Avenue. Dispensing with the petticoats and heavy corsets that weighed their mothers down a generation earlier, these middle- and upper-class women dressed in crisp, high-collared shirtwaists and long tailored skirts—garments which scandalously rose several inches off the ground when they pedaled a bicycle on Riverside Drive or strolled along gusty 23rd Street.

This army of “new women,” as they were called, embraced the progressive thinking of the later Gilded Age. Not content to be confined to the sphere of the home, they took part in the social world of theaters and restaurants. Some attended new women’s colleges like Hunter and Barnard. Many pursued something of a career: in settlement houses, as typists, or in the arts. Perhaps they lived independently. “Bachelor girl” apartments were the latest fad reported by the press, which was endlessly fascinated by the New Woman’s comings and goings.

| . |

A City Captivated

“There had been much said in the newspapers concerning the New Woman and what kind of creature she was,” stated the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in March 1895. “The pictorial papers had ridiculed her, showing her standing at bars drinking on street corners smoking cigars. This ridicule, however, would not prevent the coming of the New Woman. She would occupy any and every place, which an intelligent human being could fill: the bar, the pulpit, the legislative hall, and will be found in every trade and profession.”

Older generations were shocked by her self-reliance and sense of purpose in the wider city. Her male counterparts took her autonomy in stride and enjoyed her propensity to play tennis and ride a bike. Cultural critics worried about her morals. Pioneering women’s rights activists largely cheered her on. “The finest achievement of the new woman has been personal liberty,” wrote writer and champion of women’s freedom Winnifred Harper Cooley in 1904.

.

What Did Gertrude Tredwell Think?

The New Woman must have been an alien creature to Gertrude Tredwell. Born in 1840, Gertrude was a product of a much smaller New York that barely extended past Union Square. At the time of her birth, the city’s population hovered at approximately 300,000; by 1860, about half a million more people inhabited New York, including immigrants largely from Ireland and Germany whose lives were vastly different than that of the Tredwell family.

In the pre-Civil War city, men of means like Gertrude’s merchant father, Seabury Tredwell, occupied the outside worlds of business and politics and could freely enjoy restaurants, saloons, and sports. Women like herself, her mother, and her sisters were supposed to be “the angel of the home,” raising children, managing her household, and influencing the moral development of her family.

Like the typical New Woman, Gertrude was born into comfortable financial circumstances. But the comparison ends there. The New Woman was determined to develop independence and live freely, her movement and safety enhanced by electric streetlights and the new whirring cable cars. Gertrude, on the other hand, didn’t leave the Tredwell home. She came into the world at 29 East Fourth Street, grew up in an enclave of wealth and refinement, and died in the same house, amid a much shabbier neighborhood, 93 years later.

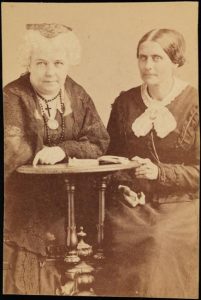

The Fight for Equal Rights

Within the span of Gertrude Tredwell’s life, the equal rights era that led to the New Woman was ushered in. After the Civil War, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony relaunched their fight for women’s rights, including the right to the vote. Working from an office on Newspaper Row, Stanton and Anthony published their weekly paper, Revolution. (“Men their rights, and nothing more; women their rights, and nothing less” was the motto.) They spoke out at lecture halls like Cooper Union at Cooper Square and Steinway Hall, on East 14th Street, both not far from the Tredwell home.

.

As the Gilded Age continued, individual women made strides. Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the nation’s first female doctor, opened a medical school for women. Despite the fact that she was legally barred from voting, Victoria Woodhull announced her quest to be the first woman president and ran on the new Equal Rights party ticket. Josephine Shaw Lowell founded the city’s Charity Organization Society. Nelly Bly and Alice Austen pioneered a type of journalism that called for social changes. Lillian Wald and Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch founded settlement houses and sparked a wider movement to boost opportunities for women and children.

.

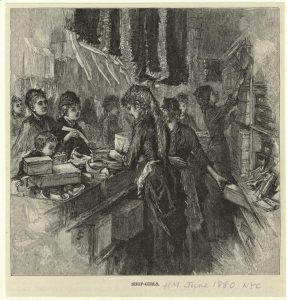

The Working Girl Makes Her Entrance

Rising at the same time as the Equal Rights movement and this new professional class of women was another Gilded Age female archetype: the working girl. With men off on the battlefields during the Civil War, women took their place. These young, often immigrant women toiled in factories, clerked in offices, cooked and cleaned in private homes, and acted as shop girls in the dry goods emporiums of Ladies Mile. After the end of the war, they continued to work. In 1869, one-fourth of all women in New York did paid labor, according to the New York Herald.

Upper class women tended to be indifferent to them. (“While yet your breakfast is progressing, and your toilet is unmade, comes forth through Chatham Street and the Bowery, a long procession of them by twos and threes to their daily labor,” wrote Fannie Fern in an 1868 essay aimed at the middle class.) Even so, the mass of working women changed the look of the city, joining men in streetcars on the way to work in the morning and back to their family home or boardinghouse when the day was done. They were the subject of plays and popular songs. No labor laws mandated that women and men in the same job get equal paychecks, so they were paid less. Harassment on the job was a problem, as was unscrupulous male bosses who wouldn’t pay up. To help, the Working Women’s Protective Union formed in 1863. Located on Bleecker Street, it was a few blocks—but worlds away—from the Tredwell home.

The Suffragist Hits the Streets

| . |

As women’s presence and power increased in New York, many coalesced behind one main goal: the right to vote. In the 1900s and 1910s, suffrage supporters rallied in Union Square and held many parades on Fifth Avenue that were catnip to the media, always obsessed with the New Woman and her sisters in arms. In 1912, about 10,000 parade marchers demanded the vote. In 1915, the number of marchers swelled to 40,000. In 1917, New York voters gave women the right to cast their ballots—three years before the 19th amendment was ratified.

Did Gertrude register to vote along with more than 414,760 women from New York State following the 1917 decision? No. But it’s hardly surprising. She would have been 77 years old by then, a member of the 19th century wealthy merchant class now living in the progressive 20th century, when the city’s population was closing in on 5 million. Her last surviving sister died in 1909, leaving Gertrude impoverished and alone.

Surely she was aware of the enormous changes in the status of women in her lifetime. She must have read newspaper accounts of Stanton and Anthony; certainly she came across the New Woman, striding along Broadway or socializing with friends. Gertrude likely watched shop girls head to factories and store counters from her window on East Fourth Street, now a rougher-edged neighborhood that was less residential and bent toward light manufacturing. What did she think of them and the new world women inhabited? If only the Merchant’s House walls could talk.

Tredwell family research contributed by William Herrlich.