Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part 2 – The Merchant Years

by Ann Haddad

A Knack for Success

Throughout his life, Seabury Tredwell had a remarkable knack for being in the right place at the right time. Or perhaps he had wise advisors who guided him carefully. However he made his decisions, they seemed to always be the right ones. He arrived in New York City to make his fortune as its wealth and reputation as a great commercial center was about to explode; thirty-five years later, he ended his mercantile career and moved uptown, narrowly escaping the Great Fire of 1835 and the economic Panic of 1837. He knew the chic neighborhood to move to and the finest country property to buy. The story of his trajectory from country farm boy to elite New York merchant is a classic success story.

Enter Seabury

Seabury arrived in New York City sometime around 1800, when the city’s population was approximately 60,500. Probably working initially as an entry-level clerk, he became one of approximately 1,100 merchants who aspired to achieve success in the growing city. He either lived with his boss (clerks often slept on the store premises), or took lodging in a boarding house. He most likely packed all of his possessions into one trunk; its contents may have been similar to that brought by a young clerk in “The Perils of Pearl Street,” : “Two pair of stockings, one vest, one pair of pantaloons, one dress-coat, two nightcaps, three cravats, one pair of boots, and one pair of slippers.” No doubt Seabury was given a sum of money by his father or another relative to tide him over financially until he was self-sufficient. For more information about Seabury’s arrival in New York City, see Meet the Tredwells: Seabury Tredwell, Part I – The Early Years.

“The Commercial Emporium of America”

With the end of the War of 1812, the lifting of British blockades, and the subsequent restoration of trade, the Port of New York began the steady economic growth that eventually led it to become the world’s busiest seaport. According to The Rise of New York Port (1939), the years from 1815-1865 saw the seaport’s greatest development into “the commercial emporium of America.” Several factors contributed to this intense and rapid growth.

The Black Ball Line

The launching of the Black Ball Line in 1818, whose four ships made regularly scheduled voyages to and from Liverpool, allowed New York to ramp up its importing of foreign goods, beating out the competitive port cities of Boston and Philadelphia. On average the packets travelled from New York to Liverpool in 23 days; the reverse trip west could take anywhere from 45 to 90 days, depending on weather and wind conditions. Due to the success of the Black Ball, other lines soon followed suit and, according to Gotham (1999) by Burrows and Wallace, by 1838 52 packet ships were shuttling from New York to Liverpool. The development of inland steamboat service by 1817 also contributed to traffic between the city and Long Island Sound and the North (now Hudson) River. Imagine the East and North River wharves lined daily with nearly 1,000 steamboats and packets!

An Ideal Harbor

The joining of the East and North Rivers created a large harbor that was ideal for foreign and domestic commercial trade. Owing to its location and tides, the harbor was well sheltered and free of the treacherous ice that could damage ships, and therefore its ports were accessible in all seasons. The depth of the water allowed large ships to come close to the wharves to load and unload cargo.

The Erie Canal – “Clinton’s Ditch”

The opening of the 363-mile Erie Canal in 1825, which connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes via the Hudson River, galvanized commerce and enabled New York to become the gateway to the rich agricultural resources of the Midwest. Those who opposed the plan to build the canal referred to it as “Clinton’s Ditch,” to ridicule Governor DeWitt Clinton, who was one of the major supporters of the project. Its route from New York City to Buffalo allowed midwestern markets to receive highly desirable imported manufactured goods; in return, domestic produce grown in the nation’s interior could be shipped (at a dramatically lower cost) to the New York markets. This exchange of more and more goods took significantly less time, increasing the velocity of trade in New York dramatically.

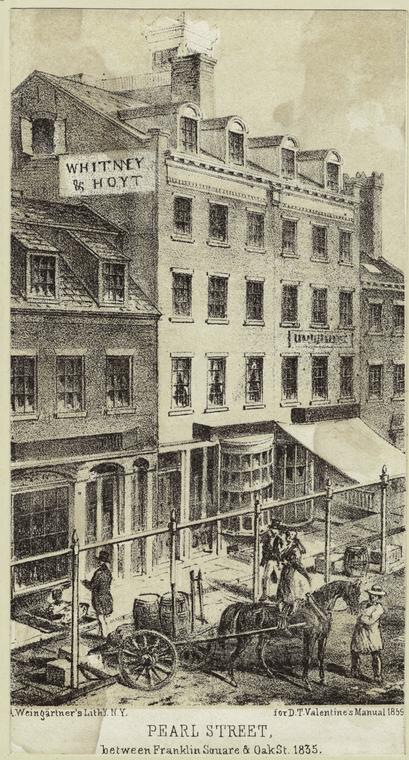

As a result of the surge and speed of trade, a new way of doing business developed in New York. Merchants sought ways to store the wealth of goods coming in and going out, while also selling them directly to consumers. The brick warehouses constructed for this purpose, which forever altered the landscape of Lower Manhattan, typically held a store/living space on the ground floor with storage areas above. The ubiquitous cart man transported the goods from the teeming wharves to the shops, where they would be hauled up by ropes to the second and third floor.

The Merchant Class

As New York’s commercial activity accelerated with each passing year, the wealth of the city and its merchants grew to unprecedented heights. According to the Commercial Directory (1823), in 1820 the value of goods imported into New York City was $26 million, and the value of exported foreign merchandise and domestic goods was nearly $12 million. The men who controlled the mercantile business became powerful and wealthy in the process and were known as the elite “Merchant Class.” Individually, those who could claim membership in this group were later referred to as “Merchant Princes.” Seabury Tredwell was indeed deserving of this distinction.

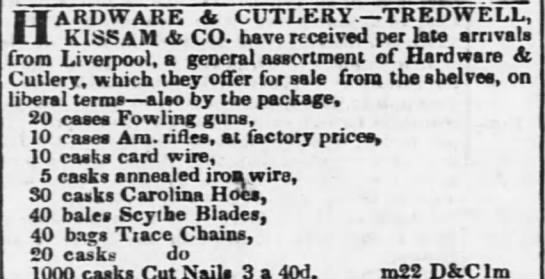

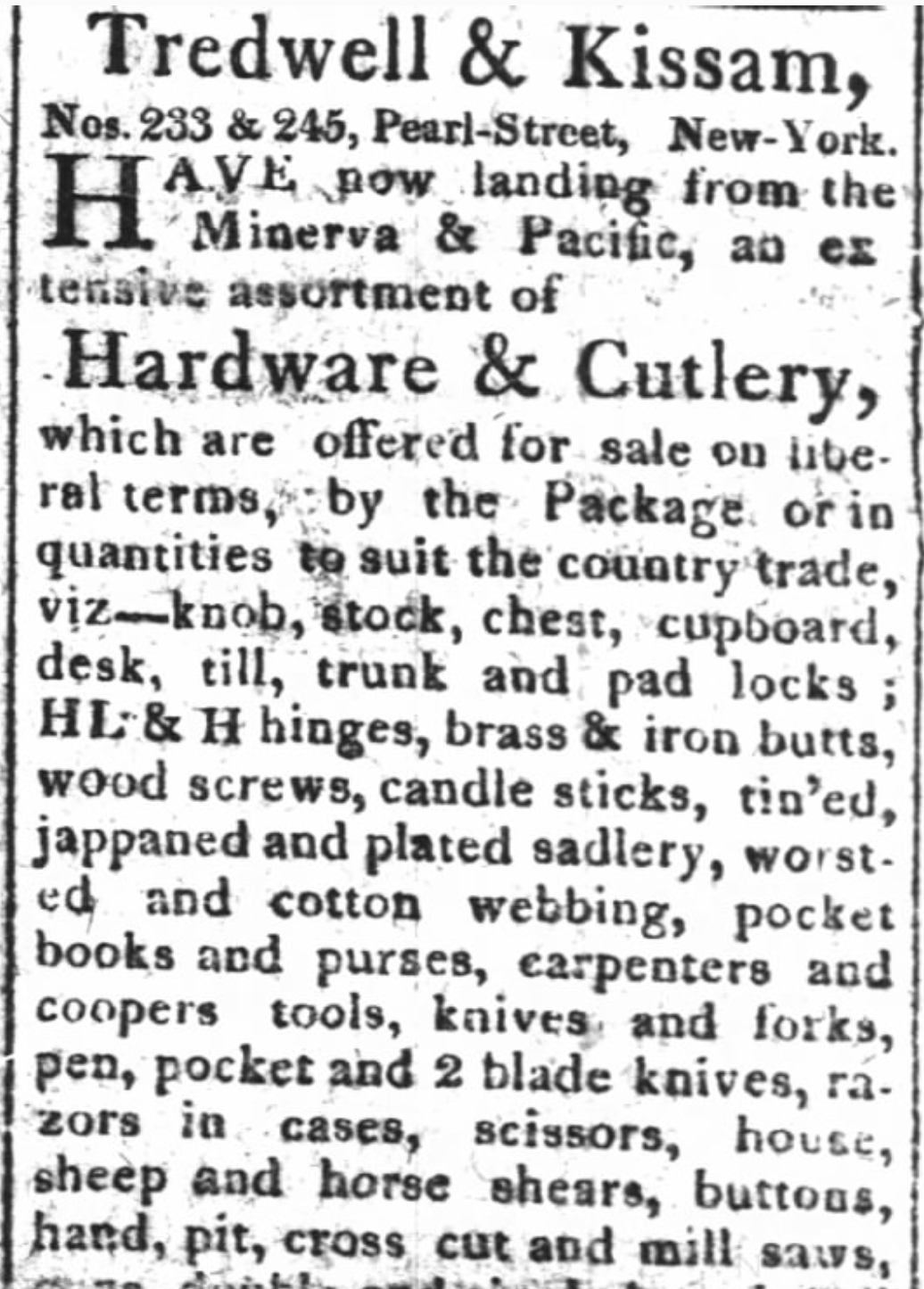

The Hardware Trade: Seabury’s Niche

We do not know if Seabury was set on becoming a hardware merchant from the start, or if he clerked for a merchant in the hardware trade, during which time he learned the details of the business. According to John C. Tucker, a New York City hardware merchant whose career overlapped with Seabury’s for several years, in the first half of the 19th century, “American Hardware was almost unknown.” Seabury purchased his goods from importers and wholesaled them from his warehouse. During his years in the hardware trade, more than 85 percent of the goods Seabury sold were imported. According to Tucker, the only American-made hardware was cut nails, and even those Seabury’s company also imported (see advertisement at right). Hence Seabury and other businessmen relied heavily on the merchant ships to deliver their goods in a timely fashion. Severe weather or a shipwreck could be a major setback to business.

It should be noted, however, that some percentage of the goods Seabury sold were American-made. At the bottom of an Evening Post advertisement (September 6, 1816), he added, “ALSO, Many articles of American Manufacture in the Hardware line.”

Trade Embargo

From his shop and warehouse on Pearl Street (see previous post for shop locations), Seabury set to work building his business and reputation as a hardware merchant. His career may have been derailed for several years during the trade embargo imposed by President Thomas Jefferson from December 1807 to March 1809, which prohibited American ships from trading in foreign ports. As a result of this effort to protect American shipping rights and to maintain neutrality amidst the raging Anglo-French conflict, activity at the seaport came to a standstill. The export trade declined by nearly 80 percent; imports by 60 percent. Many mercantile firms went out of business and unemployment among seaport workers skyrocketed. The embargo may explain the absence of Seabury’s name from the city Directory in 1808; like many other merchants, he may have had to close his business. Once the Embargo Act was repealed by Congress, in March 1809, Seabury’s name once again appeared in the Directory.

All in the Family

According to hardware merchant John C. Tucker, a “large business” was one that sold between $150,000-$200,000 worth of goods per year. Although the size of Seabury’s business is unknown, by 1815 his wealth had grown to such an extent that he took on his nephew, Joseph Kissam, as a partner, naming the firm Tredwell & Kissam. Joseph’s brother, Samuel, would join them three years later; the firm then became known as Tredwell, Kissam, and Company, and remained so until Seabury’s retirement in 1835. The partners typically shared equally in the responsibilities and profits of the company.

In The Old Merchants of New York (1863-66), author Joseph A. Scoville notes that bringing family members into the business was almost de rigueur. A merchant on the road to success “does not rest until one by one he has procured situations for all of his brothers” (or in Seabury’s case, nephews). Joseph (1790-1863) and Samuel (1796-1856), were the sons of Seabury’s sister, Elizabeth (1767-1803), and her husband Dr. Daniel Whitehead Kissam (1763-1829), of Hempstead, Long Island.

Newspapers: The Way to Advertise

Although they did some some retail business in the stores attached to their warehouses, (Seabury’s advertisements occasionally indicated that items may be purchased “from the shelves”), companies like Tredwell, Kissam and Company worked largely in wholesale. To keep his customers apprised of the goods arriving from England, Seabury advertised in the newspapers, paying a subscription of $40 per year to advertise at will, but typically three or four times a year, based on the packet schedule. (According to The Old Merchants of New York, “no respectable house would overdue the thing. [over-advertise]”). Country merchants, who would come into town several times a year to make their purchases (typically in the spring and fall), consulted the advertisements to determine which houses to visit. With these personal interactions, merchants would establish relationships with their clients, and come to understand their financial situations; this usually ensured customer loyalty, especially if the merchant extended credit to the customer when necessary.

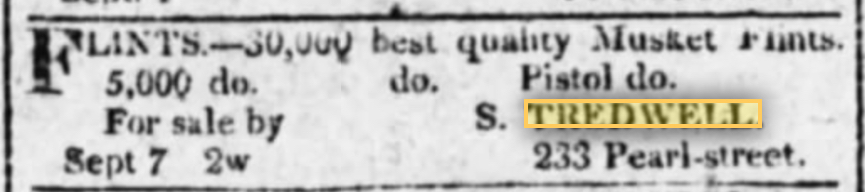

Seabury Tredwell’s first newspaper advertisement appeared on September 7, 1812. He advertised 30,000 musket flints (a form of quartz used to ignite firearms), and pistols. Tredwell & Kissam’s first advertisement appeared on August 16, 1816. As this was one year after Seabury took on a partner, it may indicate a deliberate decision on Seabury and Joseph’s part to expand the scope of their business. The ad boasts of the company’s “extensive assortment” of goods, and stress that they offer “liberal terms” for both retail and wholesale “by the package, or in quantities to suit the country trade.” In addition to hardware such as cutlery, waffle irons, tools, and cookware, the company also sold looking glasses, buttons, and ladies’ pocket books.

Newspapers like the Evening Post also regularly printed notices of ships’ arrivals in New York Port. On November 2, 1815, the ship Zodiac arrived after a 70-day voyage from Liverpool, England, bearing cargo for Tredwell & Kissam. These notices would then typically be followed by advertisements from the company announcing the goods they now had in stock.

A Pearl of A Street

Prior to the Civil War, the mile-long stretch of the East River from the Battery to Corlear’s Hook (now at Cherry Street and the East River Drive), was home to the busiest wharves. Because of their proximity to the waterfront, where ships loaded and unloaded their cargo, streets such as Pearl, (especially the blocks north of Wall Street and south of Fulton), Front, South, Wall, Pine, and lower Broadway comprised the epicenter of commercial activity. Hundreds of merchants had their shops and warehouses on these streets. According to the Commercial Directory (1823), on Pearl Street alone, 90 mercantile firms vied for customers, selling everything from dry goods and cotton to china and fine jewelry. Auction houses were plentiful as well. Tredwell, Kissam and Company was one of eight hardware merchants on Pearl Street that year.

Seabury’s Daily Routine

Whether he ventured to his warehouse on Pearl Street from his boardinghouse a short distance away, or later from his home on Dey Street, when he had to walk a few blocks further, Seabury’s daily routine probably resembled the one described in The Old Merchants of New York:

“To rise early, to get breakfast, to go down to the counting house of the firm, to open and read letters – to go out and do some business…until twelve, then to take a lunch and a glass of wine at Delmonico’s; or a few raw oysters at Downing’s; to sign checks and to attend to the finances until half past one; to go on change [the Merchant’s Exchange]; to return to the counting house, and remain until time to go to dinner, and in the old time, when such things as packet nights existed [when the packet ships would arrive at port], to stay down until ten or eleven at night, and then go home and go to bed.”

Rising Stars

Tredwell, Kissam, and Company achieved great success in the hardware business. From their early days, they cast a wide net to acquire customers. Records indicate that, in addition to New York, they did business in Connecticut, Philadelphia, Massachusetts, and Michigan.

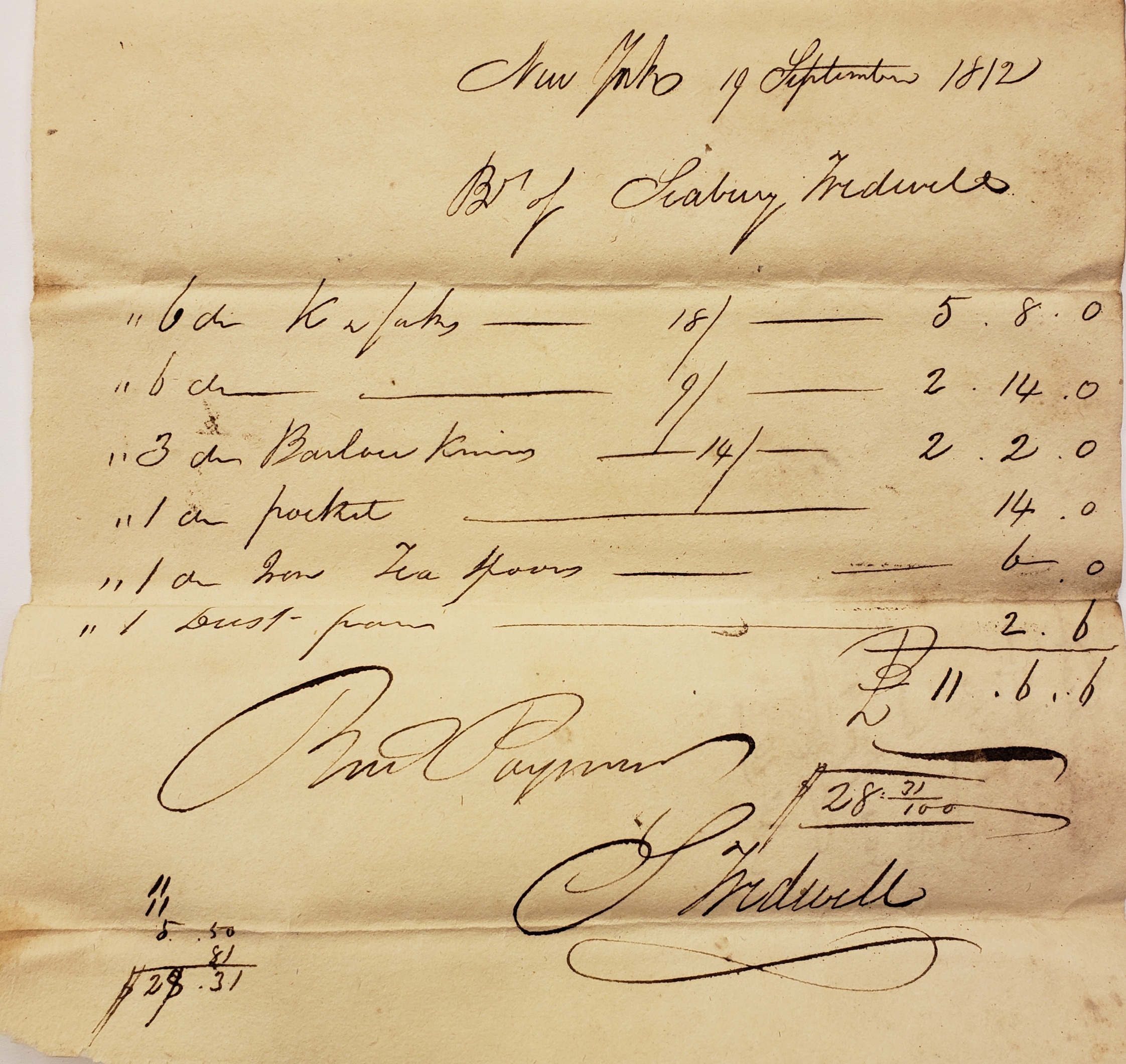

On September 19, 1812, a storekeeper in New Milford, Connecticut, named Elijah Boardman paid $28.31 to Seabury Tredwell for goods, including “three dozen barber knives, 1 dozen teaspoons, and 1 dozen dustpans.”

Another undated bill of $3.56 to Elihu Harrison of Morris, Connecticut, from Tredwell, Kissam, and Company, was for “steel knitting pins and thimbles.”

On November 22, 1827, the shop of William & Fairchild in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, ordered “brushes, spoons, thimbles, violin strings, steel traps, curry combs, sad irons, trace chains, etc.” from the firm.

As his business grew, Seabury and his partners continued the tradition of hiring clerks to do the daily work of the company while learning the trade. William Floyd-Jones, from Oyster Bay, Long Island, started out in 1831 as a clerk for “the highly respected wholesale hardware house of Tredwell, Kissam and Co.” and became a member of the firm in 1837, retiring in 1855.

Trade Tokens

Trade tokens were often used by businesses either to provide sufficient currency during times of coin shortages (especially when stores were in remote locations away from banks), to extend credit, or as a form of advertising, to let potential customers know their location and the services and goods available. In 1823, and again in 1825-26, Tredwell, Kissam and Company issued trade tokens, struck by Kettle & Sons of England, to commemorate the opening of the Erie Canal, referred to on the coin as the “Grand Canal.” According to Robert D. Leonard, a collector of trade tokens, most of the pieces made for commemoration saw limited circulation as money.

.

.

.

The South Beckons

Seabury did not limit his business to the New England or Mid-Atlantic states. Like many other merchants who realized the huge market for goods in the South, he did business with and extended credit to storekeepers in Alabama and the Carolinas. As early as 1816, Tredwell & Kissam was advertising in Southern newspapers. In an advertisement placed in The American (Fayetteville, North Carolina) on October 17, 1816, they advertised hardware and cutlery “to suit the country trade.”

Typically, a traveling salesman, or “drummer,” would venture to faraway cities to provide catalogs, collect orders, and in many cases, settle overdue accounts. In a letter to Tredwell, Kissam & Company dated January 11, 1831, from a Montgomery, Alabama, storeowner named William Shute, he references a “Mr. Smith,” who was apparently a drummer for Tredwell, Kissam, and Company: “…your Mr. Smith left here a few days ago. He said you have a fine stock of guns and Memo to order. Below we hand you an order for such goods as we are in immediate want of which you will please ship by 1st vessel for Mobile.” Shute goes on to list the desired goods, including guns, corn mills, and padlocks.

Tredwell, Kissam and Company must have had strong commercial ties to North Carolina, for in 1831 they donated $100 towards the relief of citizens of the city of Fayetteville, after a disastrous fire that took place there on May 29.

.

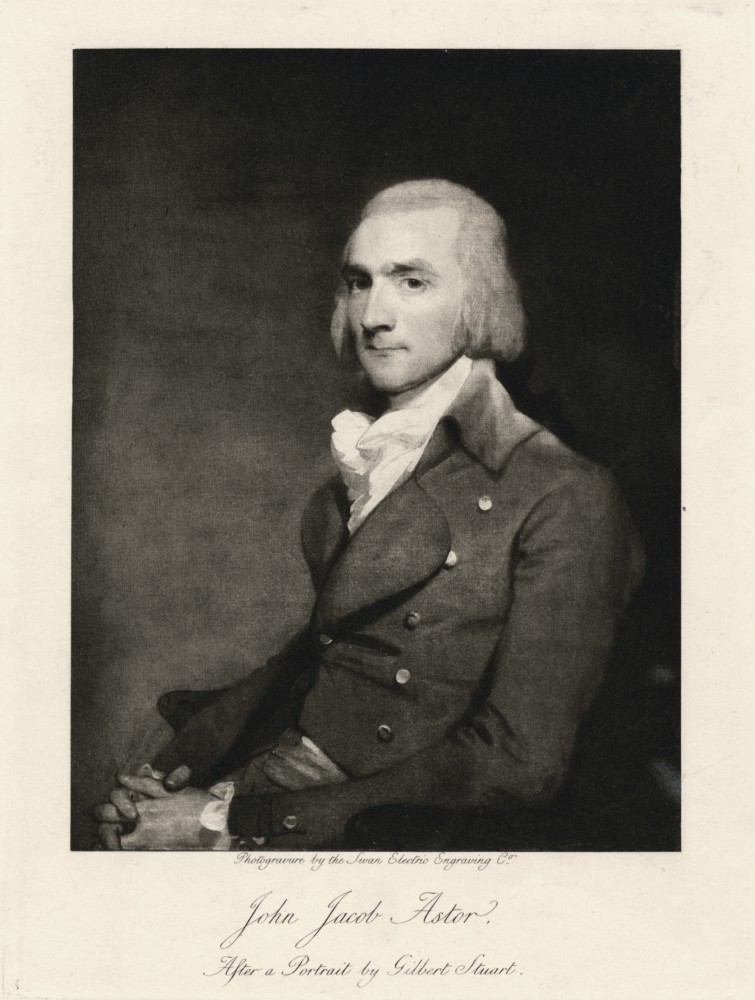

A Famous Client

Undoubtedly the most famous client of Tredwell, Kissam, and Company was John Jacob Astor (1763-1848), the German-born fur trader and real estate investor who at his death was the wealthiest man in America, with a fortune worth approximately $20 million. Records of Astor’s American Fur Company indicate that he purchased guns from Tredwell, Kissam, and Company in 1832 and 1833, for use in trade with Native Americans in exchange for furs. In a “Memorandum of Guns to be Furnished,” dated October 31, 1832, Astor gives very specific instructions as to the quality of the guns, indicating that a previous shipment had been of less than desirable quality:

“The stocks of many of the guns you gave us last spring were made of two pieces of wood united at the gap … This must not on any account be the case with the present order…Our Indians consider them not new, but old arms patched up, and in numbers instances have returned them to our traders, [illegible] them with having practiced an imposition, by selling them a mended article for one that was new and perfect in every respect. The pernicious effect of such an impression is of too much importance to our interest to be overlooked.”

The Memorandum stipulates that the specific order of 410 guns must be “ready for delivery” by April 10, 1833, which gave Tredwell, Kissam and Company six months to import the guns from England, then pack and deliver them. This order indicates the long turnaround time from ordering to acquisition and delivery of goods.

Guns and Cotton Trade

The above-mentioned orders from Shute and Astor point to a shift from hardware to guns on the part of Tredwell, Kissam, and Company. Although America was beginning to manufacture guns in small amounts (Derringer in 1810, Remington in 1816, and Colt in 1836), by 1815 the British were mass-producing millions of guns per year; Seabury’s company relied on overseas production to readily fill their large orders. The English fowling gun, used to hunt birds and fowl, was made in Birmingham, England, and was primarily sold to Native Americans.

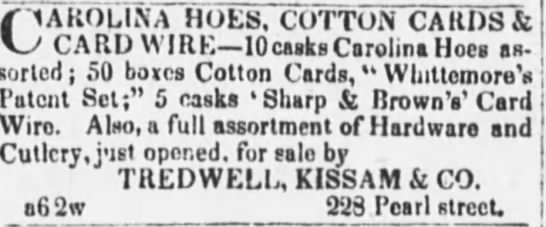

Although Seabury’s company did not engage in the rapidly growing cotton industry on a large scale (by the mid-1840s, cotton accounted for almost 45 percent of the gross national product), they did sell items that supported the trade, and, in at least one instance, sold cotton. In an advertisement in the Evening Post (December 23, 1819), the company offered “7 bales Cotton (new crop), landing from sloop Cashier.” This appears to be a one-time venture, however. What Seabury did sell in considerable quantities were cotton cards, tools used to process raw cotton in small amounts for lower-scale production. The cards disentangled and cleaned the raw cotton fibers after the cotton was picked. He also occasionally sold hemp cotton bagging, which was used to pack bales of cotton.

A Rich Man

In 1822, Lanier’s A Century of Banking in New York, 1822-1922 (1922), included Seabury in a list of “The Rich Men of 1822,” wherein the value of his personal property, from 1815 to that date, was listed as $17,500. This was quite a significant amount of money for that time, especially considering that it references only Seabury’s personal property. Seabury was living in the boardinghouse during those years, so this amount represents the value of his business and whatever chattel he owned. The real property he owned at that time (Seabury’s real estate ventures will be discussed in the next post) was not included in this estimate.

A Prince among Princes

On January 11, 1834, one year before his retirement, Seabury was a pallbearer at the funeral Thomas Seaman Townsend (1771-1834), held at St. George’s Episcopal Church (then located on Chapel Street, now Beekman), where Townsend was a vestryman. Townsend was a wealthy merchant who was a neighbor of Seabury’s on Dey Street. The names of pallbearers who joined Seabury that day reads like a list of merchant elite of New York, including such highly regarded men as Benjamin Strong, Anthony Underhill, and Stephen Van Wyck.

The End of an Era

On February 4, 1835 the following notice appeared in a New York newspaper, indicating the end of a 20 year partnership:

“The firm of Tredwell, Kissam & Co. is dissolved by mutual consent. Seabury Tredwell and Samuel Kissam retire. Either of the Partners will attend to the settlement of the business, at 228 Pearl-street.” [Signed] Seabury Tredwell, Joseph Kissam, Samuel Kissam New-York, January 31, 1835.”

The same day, Joseph Kissam announced that he had formed a new partnership with James A. Smith and William Bryce, and would continue the hardware business under the name Kissam & Co.

Although Seabury was only 55 years old when he retired, he had been in the hardware business for many years, roughly from 1800 to 1835. That is a long career by any standard. After such an extended, successful run, it is no wonder Seabury decided to retire. And no doubt he trusted that his nephew Joseph would continue the business he had worked so hard to establish.

A New Life Uptown

On October 31, 1835, Seabury sold his home on Dey Street to his former partner Joseph Kissam for $10,000. Two days later, he purchased a new home at 361 Fourth Street, for the hefty sum of $18,000. The seller was Joseph Brewster, a hatter and real estate speculator, who had built the late-Federal and Greek Revival row house three years earlier. Seabury, with his wife, Eliza, and seven children, bid farewell to the hustle and bustle of lower Manhattan, and moved to the elite Bond Street neighborhood. Thus began Seabury’s retirement, and another chapter in the life of this wealthy New York merchant.

Sources:

- Account of William & Fairchild. William B. Pennebacker Watermark Collection, 1710- ca. 1936. The Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera. Winterthur Museum. findingaid.winterthur.org: Box 3, Folder 15.

- Alabama State Archives. Record Book of William Shute, of Shute and Hackett, 1834-1837.

- Albion, Robert Greenhalgh. The Rise of New York Port [1815-1860]. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1939.

- The American. October 17, 1816, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/16/19.

- Atherton, Lewis E. “The Problem of Credit Rating in the Ante-bellum South.” The Journal of Southern History. Vol. 12, No. 4 (Nov., 1946), pp. 534-556). www.jstor.org. Accessed 3/17/19.

- Atherton, Lewis E. “Predecessors of the Commercial Drummer in the Old South.” Bulletin of the Business Historical Society. Vol. 21., No. 1 (Feb., 1947), pp. 17-24. www.jstor.org. Accessed 3/18/19.

- Barrett, Walter [pseud.] [Scoville, Joseph A.]. The Old Merchants of New York City. New York: [various publishers]: 1863-1866. www.archive.org. Accessed 4/28/19.

- Black, Samuel W. “Tools of Oppression: Cotton Cards.” Collection Spotlight at the Heinz History Center Blog. www.heinzhistorycenter.org. Accessed 3/17/19.

- Burrows, Edwin G. And Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Calendar of the American Fur Company Papers. Orders Outward, Volume 2, 1827-1833. Manuscript Collections, New-York Historical Society.

- Commercial Directory, Containing a Topographical Description…” Philadelphia: J.C. Kayser & Co., 1823.

- Davenport, Linda Haas. Haas/Davenport Homepage. www.lhaasdav.com. Accessed 3/18/19.

- Elihu Harrison Papers, 1812-1836. Litchfield Historical Society.

- Elijah Boardman Papers, 1782-1853, Litchfield Historical Society.

- Evening Post. September 11, 1812, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 5/6/19.

- Evening Post. November 2, 1815, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/23/15.

- Evening Post. August 16, 1816, p. 4. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/23/15.

- Evening Post. December 23, 1819, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 4/28/19.

- Evening Post. March 3, 1824, p. 3. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/23/15.

- Evening Post. April 4, 1832, p. 1. www.newspapers.com. Accessed 7/23/15.

- Fayetteville Weekly Observer. November 16, 1831, p. 2. www.newspapers.com. Accessed May 25, 2017.

- [Green, Asa}. The Perils of Pearl Street, Including a Taste of the Dangers of Wall Street. New York: Betts & Anstice, 1834.

- “John C. Tucker.” The Iron Age: A Review of the Hardware, Iron, and Metal Trades. Volume 49, February 18, 1892, pp. 321-22. New York: David Williams. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 4/23/19.

- Lanier, Henry W. A Century of Banking In New York, 1822-1922. New York: G.H. Doran Co., 1922.

- Leonard Jr., Robert D. “Collecting U.S. Tokens: Challenges and Rewards.” Chicago Coin Clu, 1986. wwwchicagocoinclub.org. Accessed 4/26/19.

- Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1784-1831.New York: The City of New York, 1917. www.archive.org. Accessed 3/1/19.

- Newtown Register, Thursday, February 13, 1896: www.fultonhistory.com. Accessed 3/12/19.

- New York Land Records, Conveyances, 1835-36 vol. 343-345. www.familysearch.org.

- Public Documents Printed by Order of the Senate of the United States, Volume II. United States Congressional Serial Set, Volume 239. Washington, D.C.: December 1, 1834. www.books.google.com. Accessed 3/18/19.

- Sells, Steve. Traditional Muzzleloader. www.traditionalmuzzleloader.com. Accessed 5/4/19.

- Shipping and Commercial List and New-York Price Current. February 4, 1835, p. 3. America’s Historical Newspapers. www.newsbank.com. NYPL. Accessed 6/29/17.

- Townsend, Margaret. Townsend-Townshend, 1066-1909. New York: [Press of the Broadway Publishing Company], p. 107. www.babel.hathitrust.org. Accessed 4/23/19.

This is fantastic, Annie! No previous research (mine or others) has mined this ground. And yet, if we are to understand the Tredwells and how the family fit in to the contemporary scene, we need to know about his business and how he made his money. I know this represents hours and hours of work on your part, going through all those records! Congratulations on a job very well done in putting it all together. I look forward to reading about the real estate activities in your next post.

[…] him. Although he was a New York City hardware merchant (and a very successful one: see my post Seabury Tredwell, Part 2 – The Merchant Years), he did not confine his business interests to his Pearl Street warehouse and to life on the […]

[…] gas. (For more information about Seabury Tredwell’s hardware business and investments, see Seabury Tredwell: The Merchant Years and Seabury Tredwell: Man of Opportunity). His years of hard work led to outstanding success and […]